I’m going to devote a series of posts to some (mostly online) texts that have been useful in my teaching and thinking about new media, textuality, and print technologies over the past few years. To start, I’d like to resurrect a three-year old New Yorker piece by Malcom Gladwell called “The Social Life Of Paper,” which distills the arguments of Abigail Sellen and Richard Harper’s book The Myth of the Paperless Office.

Gladwell (like Sellen and Harper) is interested in whether or not giving up paper entirely is practical or even possible. He suggests that for some tasks, paper remains the “killer app;” attempts to digitize such tasks might actually make them more difficult to do. His most compelling example, in the opening paragraph of his article, is the work of the air traffic controller:

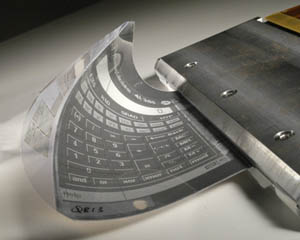

On a busy day, a typical air-traffic controller might be in charge of as many as twenty-five airplanes at a time–some ascending, some descending, each at a different altitude and travelling at a different speed. He peers at a large, monochromatic radar console, tracking the movement of tiny tagged blips moving slowly across the screen. He talks to the sector where a plane is headed, and talks to the pilots passing through his sector, and talks to the other controllers about any new traffic on the horizon. And, as a controller juggles all those planes overhead, he scribbles notes on little pieces of paper, moving them around on his desk as he does. Air-traffic control depends on computers and radar. It also depends, heavily, on paper and ink.

Gladwell goes on to make the point that this while kind of reliance on bit of paper drives productivity-managers crazy, anyone who tries to change the way that an air traffic controller works is overlooking a simple fact: the strips of paper supply a stream of “cues” that mesh beautifully with the cognitive labor of the air traffic controller; they are, Gladwell says, “physical manifestations of what goes on inside his head.”

Expanding on this example, Gladwell goes on to argue that while computers are excellent at storing information — much better than the file cabinet with its paper documents — they are often less useful for collaborative work and for the sort of intellectual tasks that are facilitated by piles of paper one can shuffle, rearrange, edit and discard on one’s desk.

“The problem that paper solves,” he writes, “is the problem that most concerns us today, which is how to support knowledge work. In fretting over paper, we have been tripped up by a historical accident of innovation, confused by the assumption that the most important invention is always the most recent. Had the computer come first — and paper second — no one would raise an eyebrow at the flight strips cluttering our air-traffic-control centers.”

This is a pretty strong statement, and I find the logic both seductive and a bit flawed. I’m seduced because I too have piles of paper all over the place, and I’d like to think that these are not simply bits of dead tree, but instead artifacts intrinsic to knowledge work. But I’m skeptical because I think it’s safe to assume that standard cognitive processes can change from generation to generation; for example, those who are growing up using ichat and texting are less likely to think of bits and scraps of paper as representative of cognitive immediacy in the same way I do.

When I’ve taught this essay, I usually also assign Sven Birkets’ Into the Electronic Millenium, a text which argues (in a somewhat Lamarckian way) that electronic mediation is pretty much rewiring our brains in a way that makes it impossible for computer-mediated youth to process information in the same way as their elders. Most of them will agree with both Gladwell and Birkets — yes, there will always be a need for paper because our brain will always process certain things certain ways, but also yes, digital technologies are changing the way that our brain works. My job is to get them to see that those two concepts contradict one another. Birkets espouses a peculiar and curmudgeonly sort of technological determinism. Gladwell, on the other hand, with his focus on an embodied way of knowing, flips the equation and wonders how best to get technology to work FOR us, instead of thinking how technology might work ON us.

I can see why my students are drawn to both arguments: even though I don’t essentially agree with either essay, I often catch myself falling into Birket’s trap of extreme technological determinism — or alternately, thinking, like Gladwell, that because a certain way of doing things seems optimal it must be the “natural” way to do it.

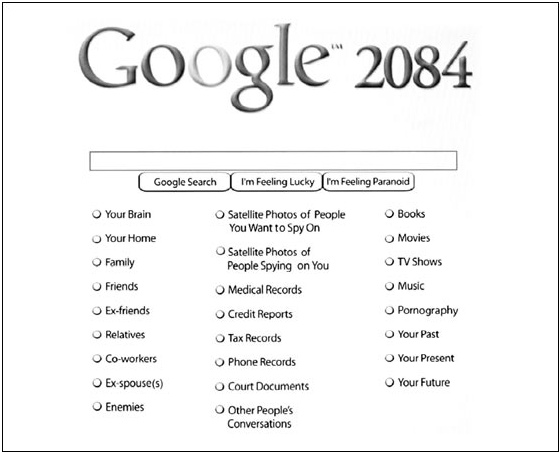

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year). Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

As for the device, well, the

As for the device, well, the

Kurzweil’s

Kurzweil’s