More fun with book metadata. Hot on the heels of Bkkeepr comes Booklert, an app that lets you keep track of the Amazon rank of your (or anyone else’s) book. Writer, thinker and social media maven Russell Davies speculated that he’d love to have such a thing for keeping track of his book. No sooner was this said than MCQN had built it; so far it has few users, but fairly well-connected ones.

Reading MCQN’s explanation I get a picture of Booklert as a time-saving tool for hypercompetitive and stat-obsessed writers, or possibly as a kind of masochistic entertainment for publishers morbidly addicted to seeing their industry flounder. Then perhaps I’m being uncharitable: assuming you accept the (deeply dodgy) premise that the only meaningful book sales are those conducted through Amazon, Booklert – or something similar – could be used to create personalized bestseller lists, adding a layer of market data to the work of trusted reviewers and curators. I’d be interested to find out which were the top-selling titles in the rest of the Institute’s personal favourites list; I’d also be interested to find out what effect a few weeks’ endorsement by a high-flying member of the digerati might have on a handful of books.

But whether or not it is, as Davies asserts, “exactly the sort of thing a major book business could have thought of, should have thought of, but didn’t”, Booklert illustrates the extent to which, in the context of the Web, most of the key developments around the future of the book do not concern the form, purposes or delivery mechanism of the book. They concern metadata: how it is collected, who owns it, who can make use of it. Whether you’re talking DRM, digitization, archiving, folksonomies or feeds, the Web brings a tendency – because an ability – to see the world less in terms of static content than in terms of dynamic patterns, flows and aggregated masses of user-generated behavior. When thus measured as units in a dynamic system, what the books themselves actually contain is only of secondary importance. What does this say about the future of serious culture in the world of information visualization?

Tag Archives: Web2.0

content syndicate

While Andrew Keen laments the decline of professionalised content production, and Publishing2.0 fuels the debate about whether there’s a distinction between ‘citizen journalism’ and the old-fashioned sort, I’ve spent the morning at Seedcamp talking with a Dubai-based entrepreur who’s blurring the distinction even further.

Content Syndicate is a distributed marketplace for buying, selling and commissioning content (By that they mean writing). Submitted content is quality-assessed first automatically and then by human editors, and can be translated by the company staff if required. They’ve grown since starting a year or so ago to 30 staff and a decent turnover.

This enterprise interests me because it picks up on some recurring themes around the the changes digitisation brings to what a writer is, and what he or she does. In some respects, this system commodifies content to an extent traditionalists will find horrifying – what writer, starting out (as many do) wanting to change the world, will feel happy having their work fed through a semiautomatic system in which they are a ‘content producer’? But while it may be helping to dismantle – in practice – the distinction between professional and amateur writers, and thus risking helping us towards Keen’s much-lamented mulch of unprofessionalised blah, but at least people are getting paid for their efforts. And you can rebut this last fear of unprofessionalised blah by saying that at least there’s some quality control going on. (The nature of the quality control is interesting too, as it’s a hybrid of automated assessment and human idiot-checking; this bears some thinking about as we consider the future of the book.)

So this enterprise points towards some ways in which we’re learning to manage, filter and also monetise this world of increasingly-pervasive ‘content everywhere’, and suggests some of the realities in which writers increasingly work. I’ll be interested to see how we adapt to this: will the erstwhile privileged position of ‘writers’ give way as these become mere grunts producing ‘content’ for the maw of the market? Or will some subtler and more nuanced bottom-up hierarchy of writing excellence emerge?

books and the man i sing

I’ve been reading failed Web1.0 entrepreneur Andrew Keen’s The Cult of the Amateur. For those who haven’t hurled it out of the window already, this is a vitriolic denouncement of the ways in which Web2.0 technology is supplanting ‘expert’ cultural agents with poor-quality ‘amateur’ content, and how this is destroying our culture.

In vehemence (if, perhaps, not in eloquence), Keen’s philippic reminded me of Alexander Pope (1688-1744). Pope was one of the first writers to popularize the notion of a ‘critic’ – and also, significantly, one of the first to make an independent living through sales of his own copyrighted works. There are some intriguing similarities in their complaints.

In the Dunciad Variorum (1738), a lengthy poem responding to the recent print boom with parodies of poor writers, information overload and a babble of voices (sound familiar, anyone?) Pope writes of ‘Martinus Scriblerus’, the supposed author of the work

He lived in those days, when (after providence had permitted the Invention of Printing as a scourge for the Sins of the learned) Paper also became so cheap, and printers so numerous, that a deluge of authors cover’d the land: Whereby not only the peace of the honest unwriting subject was daily molested, but unmerciful demands were made of his applause, yea of his money, by such as would neither earn the one, or deserve the other.

The shattered ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’, lamented by Pope in the eighteenth century when faced with a boom in printed words, is echoed by Keen when he complains that “the Web2.0 gives us is an infinitely fragmented culture in which we are hopelessly lost as to how to focus our attention and spend our limited time.” Bemoaning our gullibility, Keen wants us to return to an imagined prelapsarian state in which we dutifully consume work that has been as “professionally selected, edited and published”.

In Keen’s ideal, this selection, editing and publication ought (one presumes) to left in the hands of ‘proper’ critics – whose aesthetic in many ways still owes much to (to name but a few) Pope’s Essay On Criticism (1711), or the satirical work The Art of Sinking In Poetry (1727). But faith in these critics is collapsing. Instead, new tools that enable books to be linked give us “a hypertextual confusion of unedited, unreadable rubbish”, while publish-on-demand services swamp us in “a tidal wave of amateurish work”.

So what? you might ask. So the first explosion in the volume of published text created some of the same anxieties as this current one. But this isn’t a narrative of relentless evolutionary progress towards a utopia where everything is written, linked and searchable. The two events don’t exist on a linear trajectory; the links between Pope’s critical writings and Keen’s Canute-like protest against Web2.0 are more complex than that.

Pope’s response to the print boom was not simply to wish things could return to their previous state; rather, he popularized a critical vocabulary that both helped others to deal with it, and also – conveniently – positioned himself at the tip of the writerly hierarchy. His extensive critical writings, promoting the notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ quality writing and lambasting the less talented, served to position Pope himself as an expert. It is no coincidence that he was one of the first writers to break free of the literary patronage model and make a living out of selling his published works. The print boom that he critiqued so scatologically was the same boom that helped him to the economic independence that enabled him to criticize as he saw fit.

But where Pope’s approach to the print boom was critical engagement, Keen offers only nostalgic blustering. Where Pope was crucial in developing a language with which to deal with the print boom, Keen wishes only to preserve Pope’s approach. So, while you can choose to read the two voices, some three centuries apart, as part of a linear evolution, it’s also possible to see them as bookends (ahem) to the beginning and end of a literary era.

This era is characterized by a conceptual and practical nexus that shackles together copyright, authorship and a homogenized discourse (or ‘common high culture’, as Keen has it), delivers it through top-down and semi-monopolistic channels, and proposes always a hierarchy therein whilst tending ever more towards proliferating mass culture. In this ecology, copyright, elitism and mass populism form inseparable aspects of the same activity: publications and, by extension, writers, all busy ‘molesting’ the ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’ with competing demands on ‘his applause, yea [on] his money’.

The grading of writing by quality – the invention of a ‘high culture’ not merely determined by whichever ruler chose to praise a piece – is inextricable from the birth of the literary marketplace, new opportunities as a writer to turn oneself into a brand. In a word, the notion of ‘high culture’ is intimately bound up in the until-recently-uncontested economics of survival as a writer.

Again, so what? Well, if Keen is right and the new Web2.0 is undermining ‘high culture’, it is interesting to speculate whether this is the case because it is undermining writers’ established business model, or whether the business model is suffering because the ‘high’ concept is tottering. Either way, if Keen should be lambasted for anything it is not his puerile prose style, or for taking a stand against the often queasy techno-utopianism of some of Web2.0’s champions, but because he has, to date, demonstrated little of Pope’s nous in positioning himself to take advantage of the new economics of publishing.

Others have been more wily, though, in working out exactly what these economics might be. While researching this piece, I emailed Chris Anderson, Wired editor, Long Tail author, sometime sparring partner for Keen and vocal proponent of new, post-digital business models for writers. He told me that

“For what I do speaking is about 10x more lucrative than selling books […]. For me, it would make sense to give away the book to market my personal appearances, much as bands give away their music on MySpace to market their concerts. Thus the title of my next book, FREE, which we will try to give away in every way possible.”

Thus, for Anderson, there is life beyond copyright. It just doesn’t work the same way. And while Keen claims that Web2.0 is turning us into “a nation so digitally fragmented it’s no longer capable of informed debate” – or, in other words, that we have abandoned shared discourse and the respected authorities that arbitrate it in favor of a mulch of cultural white noise, it’s worth noting that Anderson is an example of an authority that has emerged from within this white noise. And who is making a decent living as such.

Anderson did acknowledge, though, that this might not apply to every kind of writer – “it’s just that my particular speaking niche is much in demand these days”. Anderson’s approach is all very well for ‘Big Ideas’ writers; but what, one wonders, is a poet supposed to do? A playwright? My previous post gives an example of just such a writer, though Doctorow’s podcast touches only briefly on the economics of fiction in a free-distribution model. I’ve argued elsewhere that ‘fiction’ is a complex concept and severely in need of a rethink in the context of the Web; my hunch is that while for nonfiction writers the Web requires an adjustment of distribution channels and little more, or creative work – stories – the implications are much more drastic.

I have this suspicion that, for poets and storytellers, the price of leaving copyright behind is that ‘high art’ goes with it. And, further, that perhaps that’s not as terrible as the Keens of this world might think. But that’s another article.

an excursion into old media

![]()

Last summer on a trip to Canada I picked up a copy of Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Iron Whim: a Fragmented History of Typewriting. It’s a look at our relationship with one particular piece of technology through a compound eye, investigating why so many books striving to be “literary” have typewriter keys on the cover, novelists’ feelings for their typewriters, and the complicated relationship between typewriter making and gunsmithing, among a great many other things. The book ends too soon, as Wershler-Henry doesn’t extend his thinking about typewriters and writing into broader conclusions about how technology affects writing (for that see Hugh Kenner’s The Mechanic Muse) but it’s still worth tracking down.

Last summer on a trip to Canada I picked up a copy of Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Iron Whim: a Fragmented History of Typewriting. It’s a look at our relationship with one particular piece of technology through a compound eye, investigating why so many books striving to be “literary” have typewriter keys on the cover, novelists’ feelings for their typewriters, and the complicated relationship between typewriter making and gunsmithing, among a great many other things. The book ends too soon, as Wershler-Henry doesn’t extend his thinking about typewriters and writing into broader conclusions about how technology affects writing (for that see Hugh Kenner’s The Mechanic Muse) but it’s still worth tracking down.

It did start me thinking about my use of technology. Back in junior high I was taught to type on hulking IBM Selectrics, but the last time I’d used a typewriter was to type up my college application essays. (This demonstrates my age: my baby brother’s interactions with typewriters have been limited to once finding the family typewriter in the basement; though he played with it, he says that he “never really produced anything of note on it,” and he found my query about whether or not he’d typed his college essays so ridiculous as not to merit reply.) Had I been missing out? A little investigation revealed a thriving typewriter market on eBay; for $20 (plus shipping & handling) I bought myself a Hermes Baby Featherweight. With a new ribbon and some oiling it works well, though it’s probably from the 1930s.

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a Numark PT-01) and cheap. It’s also because much of the music I’ve been listening to lately doesn’t get released on CD: dance music is still mostly vinyl-based, though it’s made the jump to MP3s without much trouble. There wasn’t much reasoning past that: after buying my record player I started buying records, almost all things I’d previously heard as MP3s. And, of course, I’d never owned a record player and I was curious what it would be like.

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a Numark PT-01) and cheap. It’s also because much of the music I’ve been listening to lately doesn’t get released on CD: dance music is still mostly vinyl-based, though it’s made the jump to MP3s without much trouble. There wasn’t much reasoning past that: after buying my record player I started buying records, almost all things I’d previously heard as MP3s. And, of course, I’d never owned a record player and I was curious what it would be like.

![]()

So what happened when I started using this technology of an older generation? The first thing you notice about using a typewriter (and I’m specifically talking about using a non-electric typewriter) is how much sense it makes. When my typewriter arrived, it was filthy. I scrubbed the gunk off the top, then unscrewed the bottom of it to get at the gunk inside it. Inside, typewriters turn out to be simple machines. A key is a lever that triggers the hammer with the key on it. The energy from my action of pressing the key makes the hammer hit the paper. There are some other mechanisms in there to move the carriage and so on, but that’s basically it.

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise: this guy has made a record player out of paper. If you look at the record, you can see from the grooves where the tracks begin and end; quiet passages don’t look the same as loud passages. You don’t get any such information from a CD: a burned CD looks different depending on how much information it has on it, but the bottom from every CD from the store looks completely identical. Without a label, you can’t tell whether a disc is an audio CD, a CD-ROM, or a DVD.

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise: this guy has made a record player out of paper. If you look at the record, you can see from the grooves where the tracks begin and end; quiet passages don’t look the same as loud passages. You don’t get any such information from a CD: a burned CD looks different depending on how much information it has on it, but the bottom from every CD from the store looks completely identical. Without a label, you can’t tell whether a disc is an audio CD, a CD-ROM, or a DVD.

![]()

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

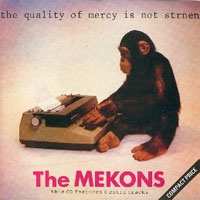

What my excursion into old technology makes me notice is how comparatively opaque our current technology is. It’s not hard to figure out how a typewriter works: were a monkey to decide that she wanted to write Hamlet, she could figure out how to use a typewriter without any problem. (Though I’m sure it exists, I couldn’t dig up any footage on YouTube of a monkey using a record player. This cat operating a record player bodes well for them, though.) It would be much more difficult, if not impossible, for even a monkey and a cat working together to figure out how to use a laptop to do the same thing.

What my excursion into old technology makes me notice is how comparatively opaque our current technology is. It’s not hard to figure out how a typewriter works: were a monkey to decide that she wanted to write Hamlet, she could figure out how to use a typewriter without any problem. (Though I’m sure it exists, I couldn’t dig up any footage on YouTube of a monkey using a record player. This cat operating a record player bodes well for them, though.) It would be much more difficult, if not impossible, for even a monkey and a cat working together to figure out how to use a laptop to do the same thing.

Obviously, designing technologies for monkeys is a foolish idea. Computers are useful because they’re abstract. I can do things with it that the makers of my Hermes Baby Featherweight couldn’t begin to imagine in 1936 (although I am quite certain than my MacBook Pro won’t be functional in seventy years). It does give me pause, however, to realize that I have no real idea at all what’s happening between when I press the A key and when an A appears on my screen. In a certain sense, the workings of my computer are closed to me.

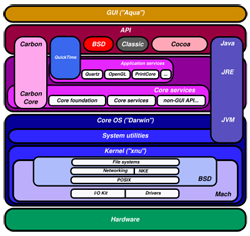

![]()

Let me add some nuance to a previous statement: not only are computers abstract, they have layers of abstraction in them. Somewhere deep inside my computer there is Unix, then on top of that there’s my operating system, then on top of that there’s Microsoft Word, and then there’s the paper I’m trying to write. (It’s more complicated than this, I know, but allow me this simplification for argument’s sake.) But these layers of abstraction are tremendously useful for the users of a computer: you don’t have to know what Unix or an operating system is to write a paper in Microsoft Word, you just need to know how to use Word. It doesn’t matter whether you’re using a Mac or a PC.

The world wide web takes this structure of abstraction layers even further. With the internet, it doesn’t matter which computer you’re on as long as you have an internet connection and a web browser. Thus I can go to another country and sit down at an internet café and check my email, which is pretty fantastic.

And yet there are still problems. Though everyone can use the Internet, it’s imperfect. The same webpage will almost certainly look different on different browsers and on different computers. This is annoying if you’re making a web page. Here at the Institute, we’ve spent ridiculous amounts of time trying to ascertain that video will play on different computers and in different web browsers, or wondering whether websites will work for people who have small screens.

A solution that pops up more and more often is Flash. Flash content works on any computer that has the Flash browser plugin, which most people have. Flash content looks exactly the same on every computer. As Ben noted yesterday, Flash video made YouTube possible, and now we can all watch videos of cats using record players.

But there’s something that nags about Flash, the same thing that bothers Ben about Flash, and in my head it’s consonant with what I notice about computers after using a typewriter or a record player. Flash is opaque. Somebody makes the Flash & you open the file on your computer, but there’s no way to figure out exactly how it works. The View Source command in your web browser will show you the relatively simple HTML that makes up this blog entry; should you be so inclined, you could figure out exactly how it worked. You could take this entry and replace all the pictures with ones that you prefer, or you could run the text through a faux-Cockney filter to make it sound even more ridiculous than it does. You can’t do the same thing with Flash: once something’s in Flash, it’s in Flash.

A couple years ago, Neal Stephenson wrote an essay called “In the Beginning Was the Command Line,” which looked at why it made a difference whether you had an open or closed operating system. It’s a bit out of date by now, as Stephenson has admitted: while the debate is the same, the terms have changed. It doesn’t really matter which operating system you use when more and more of our work is being done on web applications. The question of whether we use open or closed systems is still important: maybe it’s important to more of us, now that it’s about how we store our text, our images, our audio, our video.

A couple years ago, Neal Stephenson wrote an essay called “In the Beginning Was the Command Line,” which looked at why it made a difference whether you had an open or closed operating system. It’s a bit out of date by now, as Stephenson has admitted: while the debate is the same, the terms have changed. It doesn’t really matter which operating system you use when more and more of our work is being done on web applications. The question of whether we use open or closed systems is still important: maybe it’s important to more of us, now that it’s about how we store our text, our images, our audio, our video.