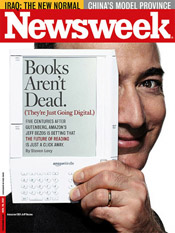

Steven Levy’s Newsweek cover story, “The Future of Reading,” is pegged to the much anticipated release of the Kindle, Amazon’s new e-book reader. While covering a lot of ground, from publishing industry anxieties, to mass digitization, Google, and speculations on longer-term changes to the nature of reading and writing (including a few remarks from us), the bulk of the article is spent pondering the implications of this latest entrant to the charred battlefield of ill-conceived gadgetry which has tried and failed for more than a decade to beat the paper book at its own game. The Kindle has a few very significant new things going for it, mainly an Internet connection and integration with the world’s largest online bookseller, and Jeff Bezos is betting that it might finally strike the balance required to attract larger numbers of readers: doing a respectable job of recreating the print experience while opening up a wide range of digital affordances.

Steven Levy’s Newsweek cover story, “The Future of Reading,” is pegged to the much anticipated release of the Kindle, Amazon’s new e-book reader. While covering a lot of ground, from publishing industry anxieties, to mass digitization, Google, and speculations on longer-term changes to the nature of reading and writing (including a few remarks from us), the bulk of the article is spent pondering the implications of this latest entrant to the charred battlefield of ill-conceived gadgetry which has tried and failed for more than a decade to beat the paper book at its own game. The Kindle has a few very significant new things going for it, mainly an Internet connection and integration with the world’s largest online bookseller, and Jeff Bezos is betting that it might finally strike the balance required to attract larger numbers of readers: doing a respectable job of recreating the print experience while opening up a wide range of digital affordances.

Speaking of that elusive balance, the bit of the article that most stood out for me was this decidely ambivalent passage on losing the “boundedness” of books:

Though the Kindle is at heart a reading machine made by a bookseller – ?and works most impressively when you are buying a book or reading it – ?it is also something more: a perpetually connected Internet device. A few twitches of the fingers and that zoned-in connection between your mind and an author’s machinations can be interrupted – ?or enhanced – ?by an avalanche of data. Therein lies the disruptive nature of the Amazon Kindle. It’s the first “always-on” book.