The uncritical embrace of technology plagues American universities and consumers alike, whose credo is “adopt first, ask questions later.” An assistant professor of english from an unnamed Midwestern liberal arts college, writes in the Chronicle of Higher Education of his dismay at the changes underway in American university libraries, where traditional stacks are left to deteriorate while money is lavished on fancy “techno-spas,” transforming research sanctuaries into digital rec centers. The article is written in response to a very a real trend, brought to wider public attention in a NY Times article in May about an initiative at the University of Texas, Austin library in which approximately 90,000 books are to be relocated from the Flawn Academic Center to other libraries around campus to make way for a “24-hour information commons.”

The uncritical embrace of technology plagues American universities and consumers alike, whose credo is “adopt first, ask questions later.” An assistant professor of english from an unnamed Midwestern liberal arts college, writes in the Chronicle of Higher Education of his dismay at the changes underway in American university libraries, where traditional stacks are left to deteriorate while money is lavished on fancy “techno-spas,” transforming research sanctuaries into digital rec centers. The article is written in response to a very a real trend, brought to wider public attention in a NY Times article in May about an initiative at the University of Texas, Austin library in which approximately 90,000 books are to be relocated from the Flawn Academic Center to other libraries around campus to make way for a “24-hour information commons.”

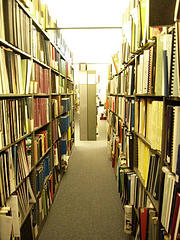

Benton’s rhapsodizing on the pleasures of the stacks can be trying:

I once had a useful, relevant book fall on my head like Newton’s apple. Perhaps it was pushed there by some ghostly scholar, one of my forebears whom I might consider myself privileged to join in the posthumous academy of spectral stack walkers.

But his overall criticism is correct. Many universities have adopted a servile stance, catering to what they perceive to be a new breed of restless, multi-tasking student. But the “customer is always right” philosophy probably isn’t doing the students any favors in the long run. A generation is coming of age lost somewhere between the old print-based hierarchies of knowledge and the new Googlesque. And they aren’t receiving much in the way of guidance. A university president needs shiny groves of sleek new computers to wow the funders and alumnae, just as he needs a winning football team. The business of universities and the business of technology march ahead together without much thought for what kind of citizen they might be producing.

From Benton:

Library administrators have had to make hard choices as costs have risen, their missions have expanded, and their budgets have failed to keep pace. But I am not so sure that the techno-spa model should be adopted so uncritically. Who will profit most from the transformation now and in the future, as fees and updates for new technologies continue indefinitely? Is that transformation really about the demands of students? If so, should we conform to their expectations, or make an effort to reshape them against the grain of the culture?

Alas, at many institutions, there is no longer much room for books on our central campuses. But we do have room for coffee bars, sports facilities, and a collection of other expensive, space-consuming amenities.

For that reason, I find it hard to accept that digitization is motivated primarily by constrained budgets and limited space. The money is there, and so is the space. It’s just that colleges want to spend the money and use the space for something else that, presumably, will make them more competitive among students who are, perhaps, more interested in amenities than education.

One purpose of universities is to provide insulation from the world at large for the cultivation of sensitive minds. Universities might consider extending this principle to technology, applying the brakes on what could be a runaway train. The Amish, who, to say the least, are loathe to adopt new technologies, ask first, when confronted with a new invention, how it might change them. We could learn something from that. The answer isn’t to hold candlelight vigils for the death of the card catalogue or the scribbled margin note, but rather to ask at each step how this is changing us, and whether we think it is a good thing.

(image by kendrak, via Flickr)