We asked Rick Prelinger for permission to cross-post this provocative piece which originally appeared in Absent Magazine

1. Why add to the population of orphaned works?

2. Don’t presume that new work improves on old

3. Honor our ancestors by recycling their wisdom

4. The ideology of originality is arrogant and wasteful

5. Dregs are the sweetest drink

6. And leftovers were spared for a reason

7. Actors don’t get a fair shake the first time around, let’s give them another

8. The pleasure of recognition warms us on cold nights and cools us in hot summers

9. We approach the future by typically roundabout means

10. We hope the future is listening, and the past hopes we are too

11. What’s gone is irretrievable, but might also predict the future

12. Access to what’s already happened is cheaper than access to what’s happening now

13. Archives are justified by use

14. Make a quilt not an advertisement

No one loves manifestos more than their writers, which means that they often require interpretation and maybe even translation into real-world language. So what I’m going to do is take my 14 points and expand them into ideas. Some of these might sound trendy, but I think they’re actually traditional – they’ve been in and around the culture for a long time.

1. Why add to the population of orphaned works?

This is meant to provoke, of course. I might as well have asked, “why make new work while old work still exists?” That would be an argument for stasis, but I’m not seeking that – I’m seeking movement.

We live in a tremendously media-rich society. Every year Americans throw away more text, sound and image than most other nations create. We’re the world capital of ephemera, and much of it has no active parent.

Orphaned works – which are works that are still owned by somebody, but a somebody that can’t be found – testify to the absurdities that arise when products of the intellect are automatically born as property, which is the way our copyright law now reads. There are millions of orphaned works out there floating in limbo. You can reproduce them or work with them if you like, but if the derivative work you make rises above a certain horizon of obscurity, you run the risk of being sued. We are trying to come up with a better set of rules, but it’s very difficult to change copyright law unless you run a studio or a record company. There are literally hundreds of thousands of great books we’d like to scan and put on the Net, but can’t because of their orphan status.

The real issue, of course, is that we need to convene and decide how deeply we want to connect culture and property. And when we’ve settled on a particular mix, we might think about whether it maximizes our freedom to speak, to learn and to inquire – in short, whether it leads to the kind of a world we’d want to live in. This will not be an easy conversation – it’s hardly even begun. But one way we can move towards more open cultural distribution and exchange is to make our own works as accessible as possible. We can do this by limiting restrictions on reuse to the absolute minimum, by using permissive licenses, like the Creative Commons licenses, that say “use me this way, it’s OK,” and by using copyright homeopathically rather than as a weapon of shock and awe.

2. Don’t presume that new work improves on old

The ephemera we produce tend to manifest ideas that fix themselves over and over again in different media. What this suggests to me is that we might be more open to letting old works speak, that our task might not be so much to make new works but to build new platforms for old works to speak from. This might mean that we weave using others’ threads, that we take positions as arrangers rather than as sculptors.

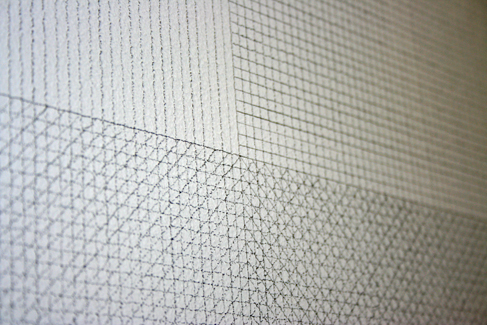

Collage often does this. In recent years we have come to understand collage largely as an assembly of small units – as the equivalent of words, syllables or even phonemes. Collage has migrated from the arts and crafts we associate with folk culture into digital culture, speeding up and fragmenting along the way. Value-free, I want to propose that collage might also work in larger units, as sentences, paragraphs, chapters, even entire books. This kind of collage works slowly and in stealth, and will ultimately affect the way that we contrast new and old works.

3. Honor our ancestors by recycling their wisdom

Take this with a grain of salt. I’m not good at ancestor worship and don’t know if I’d recognize wisdom when it’s in front of me.

But I’m going to argue here against eternalizing the present. Just because we’re in the middle of a condition that we call X doesn’t mean it’s always been X. Who would have thought that glaciers would start breaking up? Who could have predicted that honeybee populations would shrink? Who foresaw the breakup of the Soviet Union? And who among us recognizes that the 50 United States will grow to more or shrink to less than 50 as time passes?

Recycling the so-called wisdom of the past can problematize the present and encourage people to ask harder questions. When we inject history into contemporary experience, we are making an historical intervention, which can have dramatic consequences – if we listen.

This is why we’ve put ephemeral films online and why we’re now scanning books, most of which weren’t written by famous authors.

4. The ideology of originality is arrogant and wasteful

Many others have said this better than I can. It’s folly to make too much of originality. So much of what we make rests on work that’s come before. Let’s admit this and revel in it. Though it might make some people nervous, it actually cushions us in a genetic continuity of expression, and what could be more reassuring?

Last month, I went to a great lecture by Drew Daniel and Martin Schmidt from Matmos at the beautiful Hearst Mining Building. Drew laid out the history and promise of 1960s and 1970s conceptual art and talked about how it informed the work they do. One of the most provocative legacies of conceptual art was de-commodification – departing from object-oriented artmaking and from the tyranny of the art market. And yet it struck me that de-commodification had actually created its opposite. Conceptual works tended to exist primarily in their documentation, in physical traces of the work that had been created by someone so that the work would not disappear from consciousness. Documentation creates objects that are always someone’s property. The value of art documentation rests in whose work it documents and in who made the documents. We are therefore almost back where we started.

When you attend a performance, a demonstration or a happening, count the cameras and recorders. What’s the ratio of documentators to actors? Think of all the property that’s being created on the back of an event that may be nobody’s property, that may even be anti-property. Then think of identifying and unraveling those property rights forty years in the future.

5. Dregs are the sweetest drink

My partner Megan and I run a research library in San Francisco that we built around our personal book, periodical and ephemera collections. At some point it got a life of its own and started growing like mushrooms in Mendocino. Many of you know it because you’re our honored shelvers. We joke about how it’s a library full of bad ideas; I characterize it as 98% false consciousness. It’s full of outdated information, extinct procedures, self-serving explanations, ideas that never passed the smell test, and lies. And yet that’s where you find the truth. You can’t judge the past at its best, you need to confront its imperfections. And of course that’s true for the present as well.

I’ve been interested in labor history for a long time, used to collect books about it, many of them from the old Moe’s. When I began to collect industrial films I was struck by how much of the history of working people was contained in films made by corporations. In order to extract it you’ve got to engage in selective appropriation, but it’s there, often eloquently so. There’s a 1936 film called Master Hands which you can download from the Internet Archive; it’s a tribute to mass production at Chevrolet. But what it really shows is how elemental, dangerous and mind-numbing the work at Flint was. It’s a film no one else seems to have, and it’s now on the National Film Registry, but it was dregs – on a cold day in 1983, I paid a man not to throw it away.

Research is now indicating that kids who grow up on farms have fewer allergies later in life. The hypothesis is that exposure to manure immunizes them early on. City kids miss out. I hope you’ll all come visit the library, get your own dose of bad ideas and build up your immune system.

6. And leftovers were spared for a reason

Leftovers exist for lots of reasons, but my favorite reason is that they’re our raw material for performing operations on history. Whether it’s an individual filtering their family’s reality through a scrapbook or a marcher carrying a picture of a prisoner at Abu Ghraib, people use what’s left to us as leverage to document history or even change it.

7. Actors don’t get a fair shake the first time around, let’s give them another

I don’t know much about actors, really, and I’m not going to take you through the “long tail” argument. But I think that reincarnation through reuse confers importance, greater recognition, and respect on works and those who make them. Does it bring the makers money? It often does, and there are all sorts of experimental models out there. We ourselves make more money selling stock footage since we put the same footage online for free downloading.

Ubiquity raises value. Culture is an infinitely renewable resource. Does the value of “Stairway to Heaven” suffer because somewhere in America, someone’s playing it on the radio every thirty seconds?

Perhaps we’ll never know whether models of plenty beat out models of scarcity, but we may learn something as we experiment along the way and give actors a fairer shake.

8. The pleasure of recognition warms us on cold nights and cools us in hot summers

We add meaning to culture by remixing it. Putting something in a new context helps you see it with new eyes; it’s like bringing your partner home to the parents for the first time, or letting a dog loose to run in the waves.

We also infuse culture with new pleasure. When the maker who calls him or herself Otto Nomous made the short video The Fellowship of the Ring of Free Trade, he or she sought to decode the hidden prophecies contained in The Lord of the Rings and prove that it was an anarchist parable relevant to the present day. This video reveals the decoded dialogues through witty subtitles set in an Elvish typestyle. It is delightful and you can easily find it online.

Remixing is estrangement in the way the classic writers like Viktor Shklovsky and Bertolt Brecht described it. And yet the raw material remains familiar and recognizable. It’s at once a subversive and reassuring process. Some writers, like John Updike and not like Jonathan Lethem, fear the emerging mashed-up book. They hope their texts won’t be scrambled or altered, that they’ll always retain the same identity and continuity, and follow the same course. But rivers, like information, route themselves around obstacles, and the bends in rivers are where adventures happen. We’ll find new ways to experience and value old works as a consequence of mixing them into newer ones.

9. We approach the future by typically roundabout means

It’s said that storytelling is hardwired into our brains – that we respond most deeply and emotionally to storylines, characters and narrative arcs. You hear this from everyone, from folklorists to cable TV programming executives. You can’t drive a project through the distribution system if it lacks certain compulsory elements. You can, of course, employ traditional elements in novel and dramatic ways: this may get you awards.

Though I agree that stories wield power, I think this power is arbitrary. We believe in storytelling because we’ve naturalized the consensus that causes us to believe in it. There is no reason for this consensus not to change as the world changes. Storytelling as we know it is not an absolute, and it may slow the courses of culture and history. We value storytelling for its ability to wrap new skins on old skeletons, but even bones don’t last forever.

10. We hope the future is listening, and the past hopes we are too

It may be vain to hope that our works survive into the future and will be seen and listened to, but still we hope so. If we want to encourage those not yet born to think historically, we need to begin by thinking historically ourselves. This inevitably pushes us into the territory of preexisting materials.

11. What’s gone is irretrievable, but might also predict the future

For 20 years I collected old educational and industrial films. They were made to instruct and socialize young people with the objective of turning them into dependable workers, good citizens and avid consumers. 1980s audiences became fascinated with these films and a cult following developed.

I was psyched to see this happen, but became disenchanted with what to me seemed like superficial and ahistorical reactions to the films. For many people, they triggered regressive nostalgic reactions. Others treated them as surreal documents, as bizarre oddities, as the stuff of long-gone conspiracies to manufacture consensus. All of these were true in a way, but something seemed to be missing.

The breakthrough for me was to realize that these films didn’t just describe a lost past, but might also be tracing the contours of possible futures. In other words, we could see them not simply as antiquated, but as predictive. And this has in fact come true. Many of today’s suburban children live the walled-in lives of their 1950s counterparts. Corporate and government interests are conflated. We fear those we call terrorists as we once feared those we called communists.

We can’t go back to the world of the past, but sometimes the past overtakes us.

12. Access to what’s already happened is cheaper than access to what’s happening now

Sidewalk sales, dumpsters, library discard carts, Craigslist, your grandmother’s attic all contain masses of content just waiting to be cut up and reassembled. Every city has an outsider archivist who’s rescued some important collection of something from landfill and may be looking for collaborators. The past lies ready to be remade.

Yes, you can remix the present and upload it to YouTube, but they can take it down and they will, if you use content that someone else owns. The emerging digital media use electronic locks to inhibit reuse, and what you download on Saturday may vanish from your hard disk on Monday. We are beginning to turn fair use into a legal right rather than a legal defense, but we haven’t yet won.

Don’t shrink from remixing the present, but enjoy the freedom that comes with working with public domain material. The public domain is the coolest neighborhood on the frontier.

13. Archives are justified by use

This might seem obvious to you and me, but it doesn’t really work that way in the archival world. Until recently (and I generalize), archives focused more on preserving records than on providing access to them. Though this has begun to change, archives have had a really difficult time reengineering themselves and their culture to meet the vastly increased demand for their holdings.

Which brings us again to YouTube. In addition to generating lawsuits and refocusing mass culture onto a shrunken, fuzzy screen, it’s raised critical issues for archives. Media archives have tried to join the 21st century by putting little bits and pieces online. They face such opposition internally and from copyright holders that they’ve had to take baby steps. Now YouTube has raised public expectations, and it’s hard to see how any institution can meet them. In its first 12 months, YouTube built an easy-to-access online collection of some 7 million digital videos that I’d argue has become the world’s default media archives. Everything anyone does to bring archives online is now going to be measured against YouTube’s ambiguous legacy. It presents a massive collection of older and newer material, from video of Malcolm X’s complete speeches to clips of the moose I saw wandering in front yards in Anchorage. It sticks to preview mode, presenting visually degraded Flash video, so it will still get sued, but most rightsholders will rightfully regard what it does as promotion. Best of all, it allows users to upload almost anything and annotate with relative freedom. It is not an archives, but it’s outclassed archives at their own game.

In order for archives to survive while the YouTubes rule, they need to be used. And it is up to us to use the amazing things that they hold.

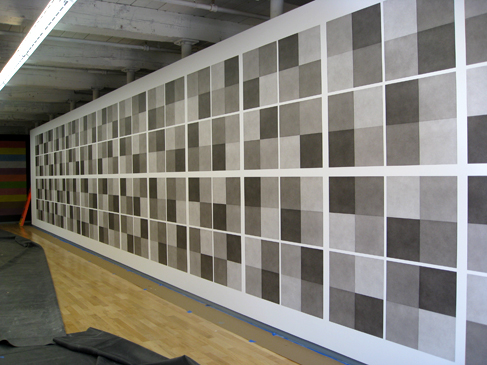

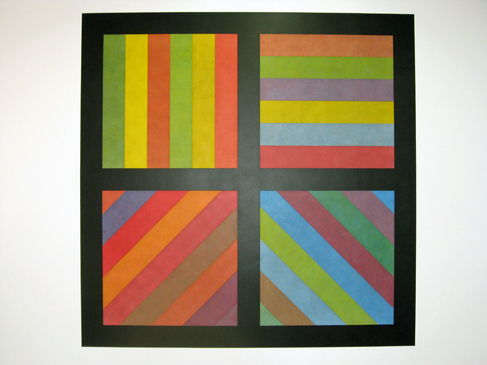

14. Make a quilt not an advertisement

Quilting is an early form of sampling. A patchwork quilt combines preexisting fabric from many sources. Quilting relies on what geeks call interoperability – the ability of elements to fit into a matrix and function together. That’s what makes the Internet work – machines and networks can talk with one another and freely exchange bits.

Interoperability requires openness. But today openness is threatened in many ways. While some companies have built business models around openness, many others haven’t. Right now, for instance, private companies are scanning books in publicly-owned and tax-exempt libraries around the world. Because the companies are paying for digitization, they control access to these new digital books, even though the books themselves may be in the public domain. Many online books let you see images of the pages, but don’t permit access to the raw text. You cannot cut and paste the text or grab it so you can index it yourself. That isn’t open, and these books don’t interoperate. You can’t weave a textual quilt using books from Project Gutenberg and books from Google. If we’re to build networked books, to freely cite the work of others and merge past and present, we need to make sure that openness is at the core of all of our activities. Cultural material needs to be shared and distributed as freely as the law allows.

But above all quilting is folk art, not corporate expression. It’s about turning leftovers into something that’s both transcendent and useful. It doesn’t have selling at its core.

Make a quilt, not an advertisement.