- Ars Technica has a review of an interesting-sounding iPhone application called Papers, designed to make it easy to carry around a library of scientific papers on your iPhone. It works with a desktop app also called Papers; it also interfaces with various scientific search engines so you can download more papers on the go. It’s not free, and it’s not for everyone, but it’s nice to see software that seems to understand that different kinds of reading need to be done differently.

- Thematically related: Adam Hodgkin argues that dedicated e-book devices generally lack an awareness of the place of the network in the task of reading; this is more natural in things like the iPhone.

- Jason Epstein’s keynote from O’Reilly’s Tools of Change conference is now online. There’s not much in here that’s particularly surprising to anyone who’s been paying attention to the field for the past few years – the Espresso Book Machine is still his hope for the future of publishing.

- And James Long, over at the digitalist has a wrap-up of Tools of Change.

- Michael Cairns points out that the trouble with e-books is that publishers still think of them only as an electronic version of the print book.

- Ted Nelson, who we mention here from time to time, has a new, self-published book out, entitled Geeks Bearing Gifts, which is his own deeply idiosyncratic take on the history of the computer and how we use them, starting from the invention of the alphabet and explaining exactly where things went wrong along the way. Ted Nelson, of course, is the inventor of hypertext among other things; I hope to have an interview with him up here soon.

- And there’s a new issue of Triple Canopy out; not all the content is up yet, but Ed Halter’s piece on Jeff Krulik and public-access TV – something of a Youtube-before-Youtube and Bidisha Banerjee & George Collins’s memoir/video game combo are worth inspection.

briefly noted

- In Mute, Tony D. Sampson reviews FLOSS+ART and Software Studies: A Lexicon, two books on software studies and digital art.

- At the Poetry Foundation, Stephanie Strickland a manifesto for e-poetry, which nicely defines how e-poetry might differ from traditional poetry. Examples are provided, though most aren’t very compelling.

- Richard Kostelanetz, who has a long history in visual poetry, has some Flash-based e-poetry in Little Red Leaves. He’s also part of a concert put on by the Electronic Music Foundation at Judson Church in New York on February 27.

- The current issue of Episteme focuses on the “epistemology of mass collaboration”; Larry Sanger, formerly of Wikipedia and currently of Citizendium, has an article about Wikipedia and expertise, one of the chief causes of his falling out with Wikipedia.

announcement: itin film on sunday

Alex Itin, the Institute’s artist-in-residence, currently has a show up in Frost Space in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. If you’re around this Sunday afternoon, he’s screening his films and giving an artist’s talk. I’m not sure exactly what he’ll be up to – Alex is nothing if not unpredictable – but it will certainly be interesting and entertaining.

wikipedia before wikipedia

I’ve been reading Tom McArthur’s Worlds of Reference: lexicography, learning and language from the clay tablet to the computer, a history of dictionaries, encyclopedias and reference materials published in 1986. The last section, titled “Tomorrow’s World” is interesting in hindsight: having looked at the major shifts that have occurred in how cultures have used lexicography, McArthur is aware that things change in unimaginable ways. He shies away from making detailed predictions about how the computer will change the dictionary or the encyclopedia; but he does find an interesting model for how the collaborative creation of knowledge might work in the future. Because I haven’t seen this mentioned online, I’ll quote this at length:

. . . I am considering something much more radically interesting: turning students on occasion into once-in-a-lifetime Sam Johnsons and Noah Websters.

At least one remarkable precedent exists for this idea: a project undertaken between 1978 and 1982 on the lower East Side of New York City which produced a “Trictionary” without a single really-truly lexicographer being involved.

The Trictionary is a 400-page trilingual English/Spanish/Chinese wordbook, covering a base vocabulary of some 3,000 items per language. Much of the basic cost was covered by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the bulk of the work was done on the premises of the Chatham Square branch of the New York Public Library, on East Broadway. The librarian there, Virginia Swift, was glad to provide the accommodation, while the original idea was developed by Jane Shapiro, a teacher of English as a Second Language at Junior High School 65, helped through all the stages the work by Mary Scherbatoskoy of ARTS (Art Resources for Teachers and Students). They organized the work, but they were not the compilers as such.

The compilation was done, as The New Yorker reports (10 May 1982) “by the spare-time energy of some 150 young people from the neighborhood”, aged between 10 and 15, two afternoons a week over three years. New York is the multilingual city par excellence, in which, as the report points out, “some of its citizens live in a kind of linguistic isolation, islanded in their languages”. The Trictionary was an effort to do something about that kind of isolation and separateness. One method used in the project was getting together a group of youngsters variously skilled in English, Spanish and Chinese and “brainstorming” over, say, the word ANIMALS written on an otherwise empty blackboard. They would think of animals and considered how they were labelled in each language, putting their triples on the board and arguing about the legitimacy of particular terms. Another method was the review session, a more sophisticated activity where a stack of blue cards with English words on them was used to create equivalent stacks in pink for Spanish and yellow for Chinese. It was out of this kind of interactive effort that the Trictionary developed, until in its final form it had a blue section with English first, a second section that was yellow and Chinese, and a third section that was pink and Spanish. Each part had three columns per page, with each language appropriately presented. In all three sections, the material was punctuated here and there by line drawings done by the youngsters themselves.

Jane Shapiro told The New Yorker that when she first went to work in the area she had had no idea what the language situation was like. The neighbourhood is about 80% Chinese and 20% Spanish-speaking, and in class she had often found herself in the position of comparing all three languages. Out of that “small United Nations” came the idea for the book, because she had often wished for such a book, but of course no right-minded publisher had ever thought of that particular combination as commercially viable or academically interesting. Additionally, and damningly, Shapiro felt that what dictionaries were available “were either too stiff or out of date or written on a linguistic level far different from that of the students”. In other words, because formal lexicography had nothing to offer, grass-roots lexicography had to serve instead.

As with Vaugelas, neighbourhood usage was the authority, and as work progressed the women and their charges actually kept away from published dictionaries so as to be sure that the words came from the youngsters themselves. Reality also prevailed, in that there is a fair quantity of legal and medical terms in the book. These were included because the children often served as interpreters between their elders and lawyers and doctors. Motivation was high, despite a shifting population of helpers, evidently because the children could see the practical utility of what they were doing. One youngster engaged in the work was Iris Chu, born in Venezuela of Chinese parents and brought to New York about five years earlier. She told The New Yorker that she made a lot of friends while working on the Trictionary (the opposite to what often happens to lexicographers), adding: “It’s funny to see it as a book now – before, it was just something we did every week. I’m really sorry it’s over. For us, it was a whole lot of fun.”

It was also a prototype for a whole new kind of educational lexicography (with or without the additional advantage, where available, of electronic and other aids). The ancient Sumerians and the medieval Scholastics would have understood the general idea of the Trictionary very well, and Comenius would certainly have approved of it. I approve of it whole-heartedly because it simply broke the mould of conventional thinking. Additionally, we can see in the brain-storming sessions and the use of the cards the two modes of lexicography creatively at work side by side: themes and word relationships on one side, alphabetic order on the other. The women of the lower East Side certainly discovered a formula for getting the taxonomic urge working in ways that are just as spectacular as any instrument that beeps, blinks and hums.

(pp. 181–183.) There doesn’t seem to be much trace of the Trictionary online; a cursory search finds the New Yorker article that McArthur refers to (behind their paywall). The New York Center for Urban Folk Culture seems to be selling copies for $5; their page for the project gives it a minimal description and has images of some of the pages.

Using the back and forth of a wikipedia article to get closer to the truth

When Jaron Lanier disparaged the Wikipedia in his 2006 essay on “the hazards of the new online collectivism” I wrote an impassioned defense including our oft-mentioned point that the most interesting thing about wikipedia articles, especially controversial ones is not necessarily what’s on the surface, but the back and forth underneath.

Jaron misunderstands the Wikipedia. In a traditional encyclopedia, experts write articles that are permanently encased in authoritative editions. The writing and editing goes on behind the scenes, effectively hiding the process that produces the published article. The standalone nature of print encyclopedias also means that any discussion about articles is essentially private and hidden from collective view. The Wikipedia is a quite different sort of publication, which frankly needs to be read in a new way. Jaron focuses on the “finished piece”, ie. the latest version of a Wikipedia article. In fact what is most illuminative is the back-and-forth that occurs between a topic’s many author/editors. I think there is a lot to be learned by studying the points of dissent; indeed the “truth” is likely to be found in the interstices, where different points of view collide. Network-authored works need to be read in a new way that allows one to focus on the process as well as the end product.

Recently a group of researchers at Palo Alto Research Center (formerly Xerox Parc) announced that they have created a prototype of a tool called “wikidashboard” which they hope will help reveal the back and forth beneath wiki articles in a way that will help readers get closer to the truth of a matter. in their own words:

“Because the information [the back and forth history of a wiikipedia artilcle] is out there for anyone to examine and to question, incorrect information can be fixed and two disputed points of view can be listed side-by-side. In fact, this is precisely the academic process for ascertaining the truth. Scholars publish papers so that theories can be put forth and debated, facts can be examined, and ideas challenged. Without publication and without social transparency of attribution of ideas and facts to individual researchers, there would be no scientific progress.”

judging a book by its contents

There’s a post at the Harper Studio blog about Stephen King’s recent denigration of Stephenie Meyer’s talents as a writer. Meyer is, of course, the author of the Twilight books, a chaste vampire saga. The post asks:

Can a book be deemed “good” or “bad” based solely of the quality of its writing?

I haven’t read the Twilight books so I can’t weigh in on King’s assessment. But it seems to me that Stephenie Meyer has activated something profound in people- mostly teenage girls – and the ability to do that may be as rare as the literary gifts of a writer like… Stephen King. Put another way: In terms of literary merit, Twilight may not be “good,” but that doesn’t mean it’s not great.

I have not read these books, though people whose taste in writing I trust more than Stephen King’s have assured me that the writing is abysmal. I have been repeatedly entertained by having what goes on in these books described to me; I have also seen the movie based upon the first of them, which I found quite thoroughly astonishing. From my perspective, it seems clear that these books are a Jesse Helms-level assault on American morality. It’s tempting to pull out Theodor Adorno, bête noire of the blogosphere: should you need a fix, his miniature essay “Morality and Style”, from Minima Moralia, will do the trick nicely.

But I’m interested not so much in Twilight‘s merit but in the attitude toward books that’s on display in this post. Books can be many things, but by this argument they stand mostly as commodity: Twilight is culturally valuable not because of anything that it might be saying – or the method in which it’s said – but because it’s reached a lot of people. By this reductionist perspective, Twilight might as well be a movie or a videogame as a book. And I think it’s this sort of thinking which is causing the downfall of publishing: for big publishers, a great book is simply one that sells a lot of copies. This is an attitude which makes sense to the people in charge of the numbers at a big publishing house, but I’m not sure that it plays so well with consumers. I can’t imagine that anyone – beside their employees – would be particularly upset if Hachette (publishers of Twilight) goes under. If a book is just a vehicle for the consumer to get content as quickly as possible, another vehicle can easily be found.

on john updike

If:book certainly isn’t an obvious venue for a John Updike remembrance. In 2006, his “The End of Authorship” vehemently misconstrued the ideals of digital publishing. At remix culture, he bristled; at collaborative reading, he balked; at the notion of books on screens, he cringed, seeking the refuge of his conventional library and its dusty tomes. In a single, hair-pullingly obtuse sentence, Updike pegged his era’s headstrong mentality: “Books traditionally have edges.”

At the time, if:book responded, to much less fanfare, with a scorched-earth rebuke in which Updike’s entire oeuvre was reduced to “juvenilia,” his brain purportedly “addled” by decades upon decades of “hero worship.”

And yet.

Updike, who died last week at 76, came to me on the recommendation of my high school English teacher, shortly after I’d realized that reading was not an altogether painful pastime. I fawned over the glittery prose of his early fiction and promptly tackled the Rabbit tetralogy; soon enough, I was writing the requisite rip-off stories and mimicking his vow “to give the mundane its beautiful due.” By now an unseemly number of Updike imitators have weaseled their way into print, but without his delicate touch, the mundane only yields the saccharine.

No detail was too minute for Updike — he was at his best when he pursued the microcosmic, finding analogs for the Big Questions in the small ones. Atomically, his sentences were as expansive and accommodating as any I’ve read. At Slate.com, Sven Birkerts eloquently elected him “the sentence guru; he showed me just what lyric accuracy a string of words could accomplish.”

Lyric accuracy, indeed. Updike’s brand of prose, however stylized, rarely sullied the acuity of his observations. The people and places that he conjured felt alive to me in a way that few had, prior to then. Those worlds were immediate. Puzzlingly, their immediacy materialized from the calm, considered measure of the prose. The perspective of an Updike piece is always enveloping. I’ll outsource my thoughts again to Birkerts: “Harry Angstrom working the remains of a caramel from his molar is a straight shunt to the living human now.”

Nowadays, I find those tribulations of suburbia moderately less gripping, but some of the passages I marveled over have retained their luster. Though it may be damning it with faint praise, I regard Updike’s work as a kind of gateway drug. Certainly it whetted my appetite for capital-L Literature, for words that faced the thrum of contemporary life without further obfuscating it. What he generated in his finest work is the crackle of a full-fledged consciousness, a voice: the sentences have a cadence, the cadence has a tone, and the tone, somehow, becomes human.

His death is, in a sense, another nail in the coffin of a kind of literary vanguard. I can understand why this blog’s readership might relish, openly or in private, the extinction of these writers, particularly given the old school’s knee-jerk aversion to new methodologies and shifting boundaries. By 2006, as the sensationally-titled “The End of Authorship” attests, it seemed that Updike opposed progress in the humanities more than he furthered it. The voguish sentiment, for better or worse, was disdain for his belletristic ways.

Still, I’m saddened by his passing. Updike and his ilk presided over fiction when more Americans read it, debated it, engaged with it. He took his writing seriously, yes, without proffering it as panacean. By the time I picked him up, to be sure, his heyday had come and gone. Legend has it, though, that the phrase “man of letters” was in those days uttered without an ironic smirk, and that one could reasonably endeavor to devote his or her life to words without appearing highfalutin or deranged. Writers could even expect to see their work in mass-market paperback editions. Imagine that.

I hope that, through the very transformation that Updike disparaged, literature in any and all forms will see an era of renewed relevance, and soon. Even he, after all, regarded books as “an encounter, in silence, of two minds.” There’s plenty to cavil about, sure — the degree of silence, the number of minds, the mode of the encounter — but at an elemental level, his assessment rings true to me. To millions of readers, Updike demonstrated the solicitous vitality of that truth, of those encounters. He will be missed.

a defense of the webcomics business model

Syndicated comics artists who are seeing their livelihood disappear as the newspapers their work appears in shrink from sight, are starting to look with more interest at the world of online webcomics. Unfortunately, they seem to misunderstand what they see or are just too quick to disapprove. Jeph Jaques, one of the early webcomic pioneers posted a wonderful description and defense of the webcomic business model. Read it here.

correspondences

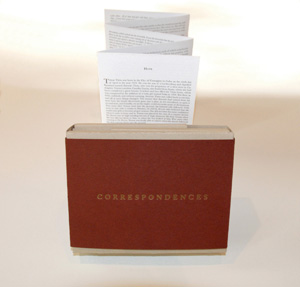

One of the most attractive books I picked up last year was a copy of Ben Greenman’s Correspondences, a collection of short stories published by Hotel St. George Press. Strictly speaking, you could argue that Correspondences isn’t a book: a maroon band surrounds an ingeniously constructed box which, when unfolded, turns out to contain three pamphlets folded accordion-style and a postcard, to which I’ll return. Each pamphlet is encircled by two stories, all of which share a theme of letter-writing. The whole thing was printed letterpress; it’s a limited edition, and each copy is signed by the author. Although it’s a relatively pricey book, I can’t imagine that the publisher’s making much money on it: clearly it cost a lot to make.

One of the most attractive books I picked up last year was a copy of Ben Greenman’s Correspondences, a collection of short stories published by Hotel St. George Press. Strictly speaking, you could argue that Correspondences isn’t a book: a maroon band surrounds an ingeniously constructed box which, when unfolded, turns out to contain three pamphlets folded accordion-style and a postcard, to which I’ll return. Each pamphlet is encircled by two stories, all of which share a theme of letter-writing. The whole thing was printed letterpress; it’s a limited edition, and each copy is signed by the author. Although it’s a relatively pricey book, I can’t imagine that the publisher’s making much money on it: clearly it cost a lot to make.

As a print book, Correspondences is very much of the present moment, inauspicious as it might be for print publishers. Hotel St. George hasn’t bothered with distribution in bookstores; the primary mode of distribution is HSG’s website. Ben Greenman has enough of a following that they’ll probably do well this way. The extraordinary form of the book is a recognition that in an age when content has become almost infinitely cheap an object needs to stand out to be bought. (One might analogously consider the CDs of Raster-Noton or Touch.) Appealing to the collector’s market makes sense for print publishing: all of Hotel St. George’s books are beautifully produced, but Correspondences takes their work to another level.

What’s most interesting to me about Ben Greenman’s book, however, is the postcard. As the box is opened, a seventh story, titled “What He’s Poised to Do,” is disclosed, printed on the box itself. A note from the author describes it as

the tale of a man who walks out on his marriage and reconsiders it from a distance. The man is staying in a hotel. While he is there, he writes ad receives a number of postcards. Some carry messages of love, others messages of regret, others still are confessions or rationalizations. There are nine postcard messages in all, not a single one of which is actually reprinted in the text of the story.

At nine points in the story there are bracketed numbers, indicating the points in the story where a postcard is read or sent; the reader is invited to take the postcard include and to compose a message to be a part of the story, and possibly part of future editions of the book. There’s a lovely tension here between the intent of the author and the wishes of the collector: filling out the postcard and dropping it in the mail destroys the unity of the book. The Mail Room at Hotel St. George’s website might convince the wary book-owner: on display are some postcards that have already been sent back. (One does note that a few of the postcard writers seem to have shied away from using the postcard that came with the book.)

The copy of Correspondences that I own – postcard still tucked in its flap – is precisely situated in time: it’s a book that prefigures its own destruction and, in a way, its own obsolescence. While this book is very firmly an object, it’s also aware of itself as a process: while the writing and the printing of the book has already happened, the reader’s response may yet happen. It’s a book that wouldn’t have existed in this form if the web hadn’t changed our understanding of how books work.

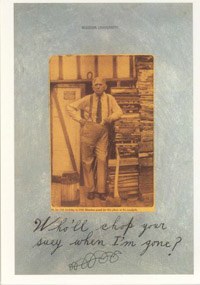

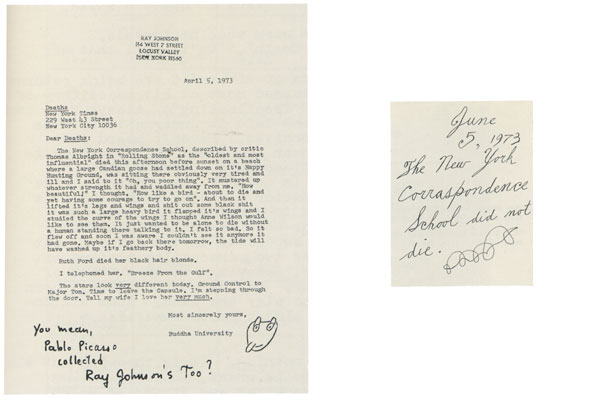

Ben Greenman’s postcard project might be seen as a recapitulation of themes present in the mail art of Ray Johnson. Trained at Black Mountain College as a painter, Johnson began making collages, which he sent to friends through the mail in the early 1950s; his use of the postal service quickly became a major focus of his art. Others followed his example; the movement he started was termed “mail art,” and it continues to this day. Although Johnson was well known and admired in the New York art world, much of his work operated outside the normal channels of the art world and he’s still surprisingly unknown to the general public. How to Draw a Bunny, John Walter’s 2002 documentary, is perhaps the easiest way in to the artist’s work. Interviews with Johnson’s friends and associates focus on the nature of their interactions with him; these interactions, it becomes clear, were as much a part of Johnson’s work as the work itself.

Ben Greenman’s postcard project might be seen as a recapitulation of themes present in the mail art of Ray Johnson. Trained at Black Mountain College as a painter, Johnson began making collages, which he sent to friends through the mail in the early 1950s; his use of the postal service quickly became a major focus of his art. Others followed his example; the movement he started was termed “mail art,” and it continues to this day. Although Johnson was well known and admired in the New York art world, much of his work operated outside the normal channels of the art world and he’s still surprisingly unknown to the general public. How to Draw a Bunny, John Walter’s 2002 documentary, is perhaps the easiest way in to the artist’s work. Interviews with Johnson’s friends and associates focus on the nature of their interactions with him; these interactions, it becomes clear, were as much a part of Johnson’s work as the work itself.

The mail was a primary method of communication for Johnson, particularly after he left New York City for Long Island in 1968; his death in 1995 came just at the cusp of broad use of the Internet to communicate. Mail art, he told James Rosenquist, was an extension of Cubism: he put things in the mail and they got spread all over the place. It was also an attempt to take art out of the commercial sphere, setting up a gift-based economy in its stead. The critic Ina Blom describes it in The Name of the Game: Ray Johnson’s Postal Performance as being

one of several art movements that tried to create an alternative space for art – a space that would be radically social and interactive, intermedial and performative. Mail art seemed to focus explicitly on the communicational aspects of both art production and reception, creating a huge network of correspondent who could communicate and exchange objects and messages through the postal system

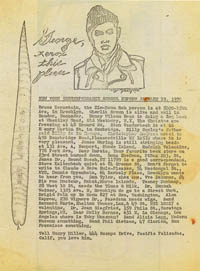

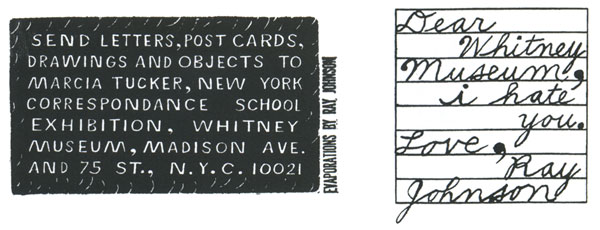

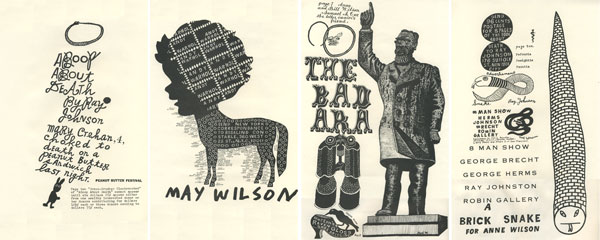

(p. 6.) Johnson ran what he called the New York Correspondence School; he used the word correspondence not simply for its reference to communication but for the way he made associations with words and graphic elements in his collages. Mailings were sent out, like this New York Correspondence School Report from January 19, 1970. William S. Wilson, in an essay entitled With Ray: The Art of Friendship, gives a sample of his working method:

(p. 6.) Johnson ran what he called the New York Correspondence School; he used the word correspondence not simply for its reference to communication but for the way he made associations with words and graphic elements in his collages. Mailings were sent out, like this New York Correspondence School Report from January 19, 1970. William S. Wilson, in an essay entitled With Ray: The Art of Friendship, gives a sample of his working method:

Walking on the Lower East Side Ray frequently saw a Ukrainian sign advertising a dance in letters which looked to him like “3-A-BABY”. He then equated “dance” with “three”, so that when three babies were involved with his life, he put the dance of three into the word “correspondence”, thereafter usually writing New York Correspondance School. Because Ray wanted to respond to accidents with spontaneities, he needed accidents to produce something more and other than he had planned to produce. In that spirit I showed him how he had happened to construct the French word,

correspondance, and gave him a copy of Baudelaire’s poem “Les Correspondances”. Later he improvised “corraspongence” and other permutations.

(p. 34) Membership was seemingly capricious and full of contradictions: members included institutions and the dead; the school committed suicide publicly at least once; and it was at best the most constant member of a baffling parade of clubs and organizations that Johnson ran, including, at random, Buddha University, the Deadpan Club, the Odilon Redon Fan Club, the Nancy Sinatra Fan Club. The Whitney Museum organized a show of the Correspondence School’s work, entitled Ray Johnson: New York Correspondance School in 1970; the museum exhibited everything Johnson’s network of collaborators mailed to it.

“The whole idea of the Correspondence School,” Johnson told Richard Bernstein in an interview with Andy Warhol’s Interview in August, 1972 “is to receive and dispense with these bits of information, because they all refer to something else. It’s just a way of having a conversation or exchange, a kind of social intercourse.” Emblematic of Johnson’s work might be his Book about Death, begun in 1963, which consisted of thirteen printed pages of collaged images and text, which were mailed individually to Clive Phillpot, chief librarian at the Museum of Modern Art, and others. (A few pages are reproduced below.) The Book about Death was discorporate, as befits a book about death; more than being unbound, Johnson made sure that none of his readers received a complete set of the pages of the book. The book could only be assembled and read in toto by the correspondents working in concert: it was a book that demanded active participation in its reading. The content as well as the form of the Book about Death request active participation: the names of his correspondents feature prominently in it, but understanding of what Johnson was doing with those names requires some knowledge of the people who had those names.

Much of Johnson’s work is interesting because it’s so dependent upon its audience. It’s not something that can exist under glass: rather, it’s a work that’s based upon personal relationships. Henry Martin writes about Ray Johnson’s work in a way that makes it sound like he’s talking about a social networking platform:

To me, Ray Johnson’s Correspondence School seems simply an attempt to establish as many significantly human relationships with as many individual people as possible. All of the relationships of which the School is made are personal relationship: relationships with a tendency towards intimacy: relationships where true experiences are truly shared and where what makes an experience true is its real participation in a secret libidinal charge. And the relationships that the artist values so highly are something he attempts to pass on to others. The classical exhortation in a Ray Johnson is “please send to . . . .” Person A will receive an object or an image and be asked to pass it on to person B, and the image will probably be appropriate to these two different people in two entirely different ways, or in terms of two entirely different chains of association. It thus becomes a kind of totem that can connect them, and whatever latent relationship may possibly exist between person A and person B becomes a little less latent and a little more real. It’s a beginning of an uncommon sense of community, and this sense of community grows as persons A and B send something back through Ray to each other, or through each other back to Ray.

(p. 186 in Ray Johnson: Correspondences.) Johnson’s work was about connection, the “art of friendship” as the title of Wilson’s essay has it. Work about personal connection has a necessarily uneasy relationship with the idea of art as a commodity; a great deal of Johnson’s work (including some of the pages of the Book about Death above) references money and remuneration in some way. Looked at through the lens of 2009, Johnson’s work seems remarkably prescient in its recognition of the importance of the network and the problems still inherent in it.

Who, if I cried out, would hear me? asks Rainer Maria Rilke at the start of the first Duino Elegy. It’s a rhetorical question that might be worth consideration: who does Rilke – or his speaker – think will hear him? Completing the line provides a superficial answer: “who” becomes someone “among the angels’ hierarchies”. But if the cry of Rilke’s speaker is directed at the angels, it’s heard by us, the readers of the poem: as a published work, the Duino Elegies function as a cry from a poet who desires to be heard. Rilke dedicated his poems to the Princess Marie von Thurn and Taxis-Hohenlohe, who brought him to Duino; she is perhaps the most proximate reader that Rilke expected. We are not the audience that Rilke envisioned; by now, everyone that Rilke might have reasonably expected to read his poem is dead.

Such authorial intent, if it existed, can’t stand in the way of the reader’s response. While reading is often a solitary act, a sense of connection can be engendered: a grieving reader might read Rilke’s poem and feel a sense of empathy, a commonality of experience. This is anticipated by Rilke’s poem (here in Stephen Mitchell’s translation):

Ah, whom can we ever turn to

in our need? Not angels, not humans,

and already the knowing animals are aware

that we are not really at home in

our interpreted world.

Rilke isn’t presumptuous enough to propose his own work as the answer to his question, though plenty of his readers would be happy to do just that. This empathy between the author and the reader is not empathy as empathy is generally understood to exist between two people: Rilke is of course dead and does not know the reader or the suffering that the reader might be undergoing. The reader may not even speak the same language as the author. Rilke is not your friend and almost certainly would not cheer you up if he were. But this is immaterial, the feeling still exists: the reader knows Rilke even if Rilke does not know the reader. To move from the specific to the overly general, this sort of response is perhaps why people describe themselves as having a visceral connection with books: our terror of print being dead isn’t so much for the books themselves but for the associations inherent in those physical objects, the sense of connection with the author even if that connection is unreciprocated.

The question of the audience of a book, and the connection of the audience to the author, is one that’s currently in a state of flux. Historically authors were something like mother sea turtles; publishing a book was something like laying eggs on a beach to hatch as they might: a reader might find a book, or a reader might not. An author could conceivably write a book for a single reader, but this doesn’t happen very often. A reader could, in the days before the Internet, find the author’s contract information from the publisher and write a letter to the author, but that happened comparatively rarely. The relationship between readers and authors is different now: after reading Greenman’s book I emailed him wondering if he’d been influenced by Ray Johnson’s work – no, he said – a behavior I find myself indulging in more and more lately. Greenman’s work, like that of Johnson’s before him, anticipates a new kind of relation between the author and the reader. The reworking of this relationship in increasingly varied ways will be the most significant aspect of the way our reading changes as it moves from the printed page to the networked screen.

Can Books and the Web Play Well Together?

The Internet, coupled with the bad economic times, has the media industry in a flurry; Institutional newspaper papers are failing regularly, magazines are reconsidering everything, and reports showing that people are just not reading – or at least not the way we are used to – has book publishers particularly concerned. So as technological advances make it easier to share online, it is publishers who are being squeezed. Especially given that no matter how things shake out, writers will still write and readers will still read.

But as the industry flails, I see hope in an emerging model. A model that I think re-embraces the traditional role of a publisher – that of connecting quality writers with interested readers – with the technology at hand.

I got this impression while reading the New York Times essay “See the Web Site, Buy the Book“, which suggests that authors are realizing the importance of a unique web presence:

[…] do book sites really help sell books? As in so much of publishing, no one quite knows. “People now latch on to a Web presence the way they once did with the book tour,” said Sloane Crosley, a publicist at Vintage/Anchor whose own book, “I Was Told There’d Be Cake,” was accompanied by a Web site featuring photographs of intricate dioramas, video and enough new material to fill a second book. “I don’t know how well the success of book Web sites can be tracked, but they do get thrown into that priceless bucket of buzz.”

First, I like that they do not know whether having a web presence will sell books, as experimentation is always a good thing. But embracing the web, I think, suggests a certain level of confidence in the book – at least for the time being. I think this also acknowledges the web as a distinct medium that doesn’t have to threaten books directly – and can maybe even work together with traditional publishing – reminiscent of the relationship between film and book industry.

Whether or not this model is adopted and developed by the current publishing industry is hard to say. It is telling that, according to the article, it is the authors taking the leadership role; paying the web agencies, out of pocket, 85% of the time.