The networked book, as an idea and as a term, has gained currency of late. A few weeks ago, Farrar Straus and Giroux launched Pulse , an adventurous marketing experiment in which they are syndicating the complete text of a new nonfiction title in blog, RSS and email. Their web developers called it, quite independently it seems, a networked book. Next week (drum roll), the institute will launch McKenzie Wark’s “GAM3R 7H30RY,” an online version of a book in progress designed to generate a critical networked discussion about video games. And, of course, the July release of Sophie is fast approaching, so soon we’ll all be making networked books.

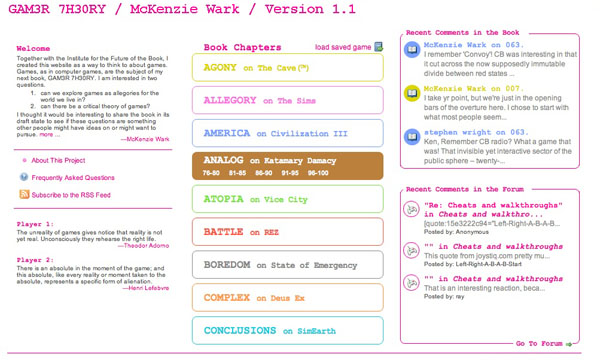

The institue will launch McKenzie Wark’s GAM3R 7H30RY Version 1.1 on Monday, May 15

The discussion following Pulse highlighted some interesting issues and made us think hard about precisely what it is we mean by “networked book.” Last spring, Kim White (who was the first to posit the idea of networked books) wrote a paper for the Computers and Writing Online conference that developed the idea a little further, based on our experience with the Gates Memory Project, where we tried to create a collaborative networked document of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Gates using popular social software tools like Flickr and del.icio.us. Kim later adapted parts of this paper as a first stab at a Wikipedia article. This was a good start.

We thought it might be useful, however, in light of recent discussion and upcoming ventures, to try to focus the definition a little bit more — to create some useful boundaries for thinking this through while holding on to some of the ambiguity. After a quick back-and-forth, we came up with the following capsule definition: “a networked book is an open book designed to be written, edited and read in a networked environment.”

Ok. Hardly Samuel Johnson, I know, but it at least begins to lay down some basic criteria. Open. Designed for the network. Still vague, but moving in a good direction. Yet already I feel like adding to the list of verbs “annotated” — taking notes inside a text is something we take for granted in print but is still quite rare in electronic documents. A networked book should allow for some kind of reader feedback within its structure. I would also add “compiled,” or “assembled,” to account for books composed of various remote parts — either freestanding assets on distant databases, or sections of text and media “transcluded” from other documents. And what about readers having conversations inside the book, or across books? Is that covered by “read in a networked environment”? — the book in a peer-to-peer ecology? Also, I’d want to add that a networked book is not a static object but something that evolves over time. Not an intersection of atoms, but an intersection of intentions. All right, so this is a little complicated.

It’s also possible that defining the networked book as a new species within the genus “book” sows the seeds of its own eventual obsolescence, bound, as we may well be, toward a post-book future. But that strikes me as too deterministic. As Dan rightly observed in his recent post on learning to read Wikipedia, the history of media (or anything for that matter) is rarely a direct line of succession — of this replacing that, and so on. As with the evolution of biological life, things tend to mutate and split into parallel trajectories. The book as the principal mode of discourse and cultural ideal of intellectual achievement may indeed be headed for gradual decline, but we believe the network has the potential to keep it in play far longer than the techno-determinists might think.

But enough with the theory and on to the practice. To further this discussion, I’ve compiled a quick-and-dirty list of projects currently out in the wild that seem to be reasonable candidates for networked bookdom. The list is intentionally small and ridden with gaps, the point being not to create a comprehensive catalogue, but to get a conversation going and collect other examples (submitted by you) of networked books, real or imaginary.

* * * * *

Everyone here at the institute agrees that Wikipedia is a networked book par excellence. A vast, interwoven compendium of popular knowledge, never fixed, always changing, recording within its bounds each and every stage of its growth and all the discussions of its collaborative producers. Linked outward to the web in millions of directions and highly visible on all the popular search indexes, Wikipedia is a city-like book, or a vast network of shanties. If you consider all its various iterations in 229 different languages it resembles more a pan-global tradition, or something approaching a real-life Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. And it is only five years in the making.

But already we begin to run into problems. Though we are all comfortable with the idea of Wikipedia as a networked book, there is significant discord when it comes to Flickr, MySpace, Live Journal, YouTube and practically every other social software, media-sharing community. Why? Is it simply a bias in favor of the textual? Or because Wikipedia – the free encyclopedia — is more closely identified with an existing genre of book? Is it because Wikipedia seems to have an over-arching vision (free, anyone can edit it, neutral point of view etc.) and something approaching a coherent editorial sensibility (albeit an aggregate one), whereas the other sites just mentioned are simply repositories, ultimately shapeless and filled with come what may? This raises yet more questions. Does a networked book require an editor? A vision? A direction? Coherence? And what about the blogosphere? Or the world wide web itself? Tim O’Reilly recently called the www one enormous ebook, with Google and Yahoo as the infinitely mutable tables of contents.

Ok. So already we’ve opened a pretty big can of worms (Wikipedia tends to have that effect). But before delving further (and hopefully we can really get this going in the comments), I’ll briefly list just a few more experiments.

>>> Code v.2 by Larry Lessig

From the site:

“Lawrence Lessig first published Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace in 1999. After five years in print and five years of changes in law, technology, and the context in which they reside, Code needs an update. But rather than do this alone, Professor Lessig is using this wiki to open the editing process to all, to draw upon the creativity and knowledge of the community. This is an online, collaborative book update; a first of its kind.

“Once the project nears completion, Professor Lessig will take the contents of this wiki and ready it for publication.”

Recently discussed here, there is the new book by Yochai Benkler, another intellectual property heavyweight:

>>> The Wealth of Networks

Yale University Press has set up a wiki for readers to write collective summaries and commentaries on the book. PDFs of each chapter are available for free. The verdict? A networked book, but not a well executed one. By keeping the wiki and the text separate, the publisher has placed unnecessary obstacles in the reader’s path and diminished the book’s chances of success as an organic online entity.

>>> Our very own GAM3R 7H30RY

On Monday, the institute will launch its most ambitious networked book experiment to date, putting an entire draft of McKenzie Wark’s new book online in a compelling interface designed to gather reader feedback. The book will be matched by a series of free-fire discussion zones, and readers will have the option of syndicating the book over a period of nine weeks.

>>> The afore-mentioned Pulse by Robert Frenay.

Again, definitely a networked book, but frustratingly so. In print, the book is nearly 600 pages long, yet they’ve chosen to serialize it a couple pages at a time. It will take readers until November to make their way through the book in this fashion — clearly not at all the way Frenay crafted it to be read. Plus, some dubious linking made not by the author but by a hired “linkologist” only serves to underscore the superficiality of the effort. A bold experiment in viral marketing, but judging by the near absence of reader activity on the site, not a very contagious one. The lesson I would draw is that a networked book ought to be networked for its own sake, not to bolster a print commodity (though these ends are not necessarily incompatible).

>>> The Quicksilver Wiki (formerly the Metaweb)

A community site devoted to collectively annotating and supplementing Neal Stephenson’s novel “Quicksilver.” Currently at work on over 1,000 articles. The actual novel does not appear to be available on-site.

>>> Finnegans Wiki

A complete version of James Joyce’s demanding masterpiece, the entire text placed in a wiki for reader annotation.

>>> There’s a host of other literary portals, many dating back to the early days of the web: Decameron Web, the William Blake Archive, the Walt Whitman Archive, the Rossetti Archive, and countless others (fill in this list and tell us what you think).

Lastly, here’s a list of book blogs — not blogs about books in general, but blogs devoted to the writing and/or discussion of a particular book, by that book’s author. These may not be networked books in themselves, but they merit study as a new mode of writing within the network. The interesting thing is that these sites are designed to gather material, generate discussion, and build a community of readers around an eventual book. But in so doing, they gently undermine the conventional notion of the book as a crystallized object and begin to reinvent it as an ongoing process: an evolving artifact at the center of a conversation.

Here are some I’ve come across (please supplement). Interestingly, three of these are by current or former editors of Wired. At this point, they tend to be about techie subjects:

>>> An exception is Without Gods: Toward a History of Disbelief by Mitchell Stephens (another institute project).

“The blog I am writing here, with the connivance of The Institute for the Future of the Book, is an experiment. Our thought is that my book on the history of atheism (eventually to be published by Carroll and Graf) will benefit from an online discussion as the book is being written. Our hope is that the conversation will be joined: ideas challenged, facts corrected, queries answered; that lively and intelligent discussion will ensue. And we have an additional thought: that the web might realize some smidgen of benefit through the airing of this process.”

>>> Searchblog

John Battelle’s daily thoughts on the business and technology of web search, originally set up as a research tool for his now-published book on Google, The Search.

>>> The Long Tail

Similar concept, “a public diary on the way to a book” chronicling “the shift from mass markets to millions of niches.” By current Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson.

>>> Darknet

JD Lasica’s blog on his book about Hollywood’s war against amateur digital filmmakers.

>>> The Technium

Former Wired editor Kevin Kelly is working through ideas for a book:

“As I write I will post here. The purpose of this site is to turn my posts into a conversation. I will be uploading my half-thoughts, notes, self-arguments, early drafts and responses to others’ postings as a way for me to figure out what I actually think.”

>>> End of Cyberspace by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

Pang has some interesting thoughts on blogs as research tools:

“This begins to move you to a model of scholarly performance in which the value resides not exclusively in the finished, published work, but is distributed across a number of usually non-competitive media. If I ever do publish a book on the end of cyberspace, I seriously doubt that anyone who’s encountered the blog will think, “Well, I can read the notes, I don’t need to read the book.” The final product is more like the last chapter of a mystery. You want to know how it comes out.

“It could ultimately point to a somewhat different model for both doing and evaluating scholarship: one that depends a little less on peer-reviewed papers and monographs, and more upon your ability to develop and maintain a piece of intellectual territory, and attract others to it– to build an interested, thoughtful audience.”

* * * * *

This turned out much longer than I’d intended, and yet there’s a lot left to discuss. One question worth mulling over is whether the networked book is really a new idea at all. Don’t all books exist over time within social networks, “linked” to countless other texts? What about the Talmud, the Jewish compendium of law and exigesis where core texts are surrounded on the page by layers of commentary? Is this a networked book? Or could something as prosaic as a phone book chained to a phone booth be considered a networked book?

In our discussions, we have focused overwhelmingly on electronic books within digital networks because we are convinced that this is a major direction in which the book is (or should be) heading. But this is not to imply that the networked book is born in a vacuum. Naturally, it exists in a continuum. And just as our concept of the analog was not fully formed until we had the digital to hold it up against, perhaps our idea of the book contains some as yet undiscovered dimensions that will be revealed by investigating the networked book.

Momus is a Scottish pop musician, based in Berlin, who writes smart and original things about art and technology. He blogs a wonderful blog called

Momus is a Scottish pop musician, based in Berlin, who writes smart and original things about art and technology. He blogs a wonderful blog called