This morning I’m giving a talk on networked books at a libraries and technology conference up at Bentley College, just outside of Boston. The program, “Social Networking: Plugging New England Libraries into Web 2.0,” has been organized by NELINET, a consortium of over 600 academic, public and special libraries across the six New England states, so librarians and info services folks from all over the northeast will be in attendance.

In many ways, our publishing projects fit quite comfortably under the broad, buzz-ridden rubrique of Web 2.0: books as social spaces, “architecture of participation,” “treat your users as co-developers” (or, in our experiments, readers as co-authors). I’m going to be discussing all of these things, but I’m also planning to look at books in a slightly different way: as processes, or movements, in time.

Lately, when we’re explaining our work to the unitiated, Bob picks up whatever book is lying nearby (yes, we do have books), holds it up in the air and indicates with his hands the space on either side of the object: “here’s all the stuff that came before the book, and here’s all the stuff that came after.” That’s the spectrum that networked reading and writing opens up, and what the Institute are trying to do is to explore and open up new ways of thinking about all these different stages of creative flow that go into and out of books. Of our recent projects, you could say that Without Gods focuses on the “into” end of the evolutionary span while GAM3R 7H30RY deals more with the “out of.” Naturally, books have always been this way, but computers and networks make all of it manifest in a very new way that’s difficult to make sense of.

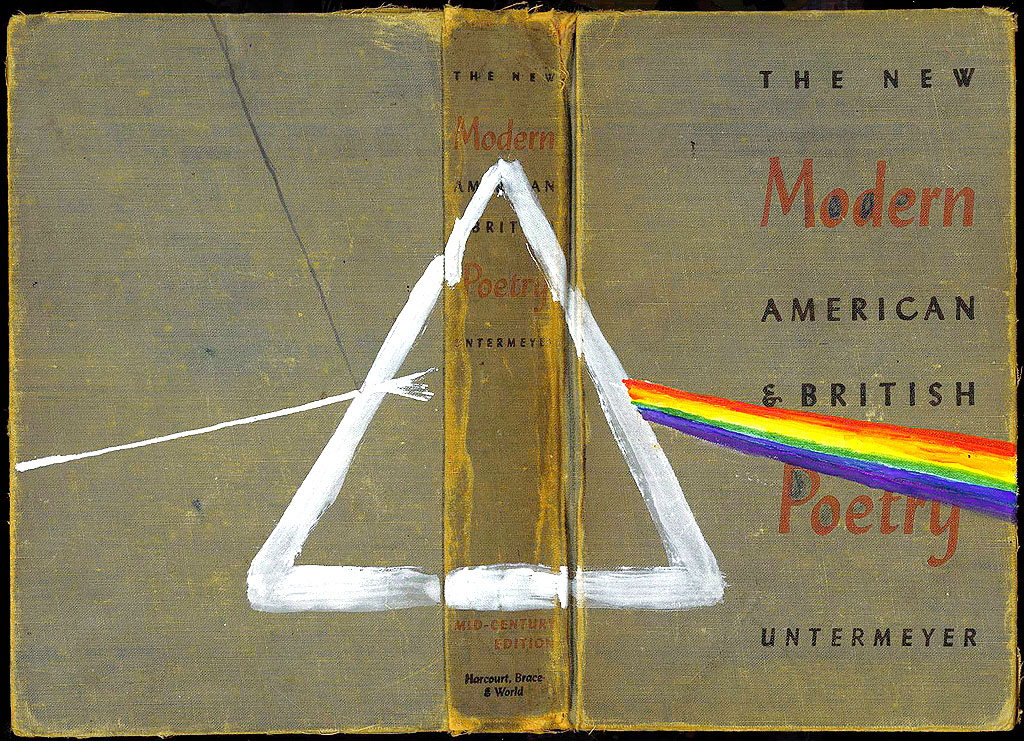

That’s what the picture up top is getting at, in a joshing way. Bob’s depiction of books in time reminded me of the famous prism image on the cover of Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon” where pure white light turns to rainbow as it passes through the glass. I was joking about this with Alex Itin, our artblogger in residence, and yesterday he cobbled together this excellent image (and ripped the audio), which I’m going to work into my talk somehow. Wish me luck.

(Incidentally, “Books in Time” is the name of a wonderful essay by Carla Hesse, a Berkeley historian, which has been a big influence on what we do.)

Category Archives: Web2.0

an excursion into old media

![]()

Last summer on a trip to Canada I picked up a copy of Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Iron Whim: a Fragmented History of Typewriting. It’s a look at our relationship with one particular piece of technology through a compound eye, investigating why so many books striving to be “literary” have typewriter keys on the cover, novelists’ feelings for their typewriters, and the complicated relationship between typewriter making and gunsmithing, among a great many other things. The book ends too soon, as Wershler-Henry doesn’t extend his thinking about typewriters and writing into broader conclusions about how technology affects writing (for that see Hugh Kenner’s The Mechanic Muse) but it’s still worth tracking down.

Last summer on a trip to Canada I picked up a copy of Darren Wershler-Henry’s The Iron Whim: a Fragmented History of Typewriting. It’s a look at our relationship with one particular piece of technology through a compound eye, investigating why so many books striving to be “literary” have typewriter keys on the cover, novelists’ feelings for their typewriters, and the complicated relationship between typewriter making and gunsmithing, among a great many other things. The book ends too soon, as Wershler-Henry doesn’t extend his thinking about typewriters and writing into broader conclusions about how technology affects writing (for that see Hugh Kenner’s The Mechanic Muse) but it’s still worth tracking down.

It did start me thinking about my use of technology. Back in junior high I was taught to type on hulking IBM Selectrics, but the last time I’d used a typewriter was to type up my college application essays. (This demonstrates my age: my baby brother’s interactions with typewriters have been limited to once finding the family typewriter in the basement; though he played with it, he says that he “never really produced anything of note on it,” and he found my query about whether or not he’d typed his college essays so ridiculous as not to merit reply.) Had I been missing out? A little investigation revealed a thriving typewriter market on eBay; for $20 (plus shipping & handling) I bought myself a Hermes Baby Featherweight. With a new ribbon and some oiling it works well, though it’s probably from the 1930s.

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a Numark PT-01) and cheap. It’s also because much of the music I’ve been listening to lately doesn’t get released on CD: dance music is still mostly vinyl-based, though it’s made the jump to MP3s without much trouble. There wasn’t much reasoning past that: after buying my record player I started buying records, almost all things I’d previously heard as MP3s. And, of course, I’d never owned a record player and I was curious what it would be like.

Next I got myself a record player. I would like to note that this acquisition didn’t immediately follow my buying a typewriter: old technology isn’t that slippery a slope. This was because I happened to see a record player that was cute as a button (a Numark PT-01) and cheap. It’s also because much of the music I’ve been listening to lately doesn’t get released on CD: dance music is still mostly vinyl-based, though it’s made the jump to MP3s without much trouble. There wasn’t much reasoning past that: after buying my record player I started buying records, almost all things I’d previously heard as MP3s. And, of course, I’d never owned a record player and I was curious what it would be like.

![]()

So what happened when I started using this technology of an older generation? The first thing you notice about using a typewriter (and I’m specifically talking about using a non-electric typewriter) is how much sense it makes. When my typewriter arrived, it was filthy. I scrubbed the gunk off the top, then unscrewed the bottom of it to get at the gunk inside it. Inside, typewriters turn out to be simple machines. A key is a lever that triggers the hammer with the key on it. The energy from my action of pressing the key makes the hammer hit the paper. There are some other mechanisms in there to move the carriage and so on, but that’s basically it.

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise: this guy has made a record player out of paper. If you look at the record, you can see from the grooves where the tracks begin and end; quiet passages don’t look the same as loud passages. You don’t get any such information from a CD: a burned CD looks different depending on how much information it has on it, but the bottom from every CD from the store looks completely identical. Without a label, you can’t tell whether a disc is an audio CD, a CD-ROM, or a DVD.

A record player’s more complicated than a typewriter, but it’s still something that you can understand. Technologically, a record player isn’t very complicated: you need a motor that turns the record at a certain speed, a pickup, something to turn the vibrations into sound, and an amplifier. Even without amplification, the needle in the groove makes a tiny but audible noise: this guy has made a record player out of paper. If you look at the record, you can see from the grooves where the tracks begin and end; quiet passages don’t look the same as loud passages. You don’t get any such information from a CD: a burned CD looks different depending on how much information it has on it, but the bottom from every CD from the store looks completely identical. Without a label, you can’t tell whether a disc is an audio CD, a CD-ROM, or a DVD.

![]()

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

There’s something admirably simple about this. On my typewriter, pressing the A key always gets you the letter A. It may be an uppercase A or a lowercase a, but it’s always an A. (Caveat: if it’s oiled and in good working condition and you have a good ribbon. There are a lot of things that can go wrong with a typewriter.) This is blatantly obvious. It only becomes interesting when you set it against the way we type now. If I type an A key on my laptop, sometimes an A appears on my screen. If my computer’s set to use Arabic or Persian input, typing an A might get me the Arabic letter ش. But if I’m not in a text field, typing an A won’t get me anything. Typing A in the Apple Finder, for example, selects a file starting with that letter. Typing an A in a web browser usually doesn’t do anything at all. On a computer, the function of the A key is context-specific.

What my excursion into old technology makes me notice is how comparatively opaque our current technology is. It’s not hard to figure out how a typewriter works: were a monkey to decide that she wanted to write Hamlet, she could figure out how to use a typewriter without any problem. (Though I’m sure it exists, I couldn’t dig up any footage on YouTube of a monkey using a record player. This cat operating a record player bodes well for them, though.) It would be much more difficult, if not impossible, for even a monkey and a cat working together to figure out how to use a laptop to do the same thing.

What my excursion into old technology makes me notice is how comparatively opaque our current technology is. It’s not hard to figure out how a typewriter works: were a monkey to decide that she wanted to write Hamlet, she could figure out how to use a typewriter without any problem. (Though I’m sure it exists, I couldn’t dig up any footage on YouTube of a monkey using a record player. This cat operating a record player bodes well for them, though.) It would be much more difficult, if not impossible, for even a monkey and a cat working together to figure out how to use a laptop to do the same thing.

Obviously, designing technologies for monkeys is a foolish idea. Computers are useful because they’re abstract. I can do things with it that the makers of my Hermes Baby Featherweight couldn’t begin to imagine in 1936 (although I am quite certain than my MacBook Pro won’t be functional in seventy years). It does give me pause, however, to realize that I have no real idea at all what’s happening between when I press the A key and when an A appears on my screen. In a certain sense, the workings of my computer are closed to me.

![]()

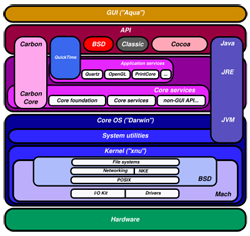

Let me add some nuance to a previous statement: not only are computers abstract, they have layers of abstraction in them. Somewhere deep inside my computer there is Unix, then on top of that there’s my operating system, then on top of that there’s Microsoft Word, and then there’s the paper I’m trying to write. (It’s more complicated than this, I know, but allow me this simplification for argument’s sake.) But these layers of abstraction are tremendously useful for the users of a computer: you don’t have to know what Unix or an operating system is to write a paper in Microsoft Word, you just need to know how to use Word. It doesn’t matter whether you’re using a Mac or a PC.

The world wide web takes this structure of abstraction layers even further. With the internet, it doesn’t matter which computer you’re on as long as you have an internet connection and a web browser. Thus I can go to another country and sit down at an internet café and check my email, which is pretty fantastic.

And yet there are still problems. Though everyone can use the Internet, it’s imperfect. The same webpage will almost certainly look different on different browsers and on different computers. This is annoying if you’re making a web page. Here at the Institute, we’ve spent ridiculous amounts of time trying to ascertain that video will play on different computers and in different web browsers, or wondering whether websites will work for people who have small screens.

A solution that pops up more and more often is Flash. Flash content works on any computer that has the Flash browser plugin, which most people have. Flash content looks exactly the same on every computer. As Ben noted yesterday, Flash video made YouTube possible, and now we can all watch videos of cats using record players.

But there’s something that nags about Flash, the same thing that bothers Ben about Flash, and in my head it’s consonant with what I notice about computers after using a typewriter or a record player. Flash is opaque. Somebody makes the Flash & you open the file on your computer, but there’s no way to figure out exactly how it works. The View Source command in your web browser will show you the relatively simple HTML that makes up this blog entry; should you be so inclined, you could figure out exactly how it worked. You could take this entry and replace all the pictures with ones that you prefer, or you could run the text through a faux-Cockney filter to make it sound even more ridiculous than it does. You can’t do the same thing with Flash: once something’s in Flash, it’s in Flash.

A couple years ago, Neal Stephenson wrote an essay called “In the Beginning Was the Command Line,” which looked at why it made a difference whether you had an open or closed operating system. It’s a bit out of date by now, as Stephenson has admitted: while the debate is the same, the terms have changed. It doesn’t really matter which operating system you use when more and more of our work is being done on web applications. The question of whether we use open or closed systems is still important: maybe it’s important to more of us, now that it’s about how we store our text, our images, our audio, our video.

A couple years ago, Neal Stephenson wrote an essay called “In the Beginning Was the Command Line,” which looked at why it made a difference whether you had an open or closed operating system. It’s a bit out of date by now, as Stephenson has admitted: while the debate is the same, the terms have changed. It doesn’t really matter which operating system you use when more and more of our work is being done on web applications. The question of whether we use open or closed systems is still important: maybe it’s important to more of us, now that it’s about how we store our text, our images, our audio, our video.

social powerpointing, or, the darker side of flash

SlideShare is a new web application that lets you upload PowerPoint (.ppt and .pps) or OpenOffice (.odp) slideshows to the web for people to use and share. The site (which is in an invite-only beta right now, though accounts are granted within minutes of a request) feels a lot like the now-merged Google Video and YouTube. Slideshows come up with a unique url, copy-and-paste embed code for bloggers, tags, a comment stream and links to related shows. Clicking a “full” button on the viewer controls enlarges the slideshow to fill up most of the screen. Here’s one I found humorously diagramming soccer strategies from various national teams:

Another resemblance to Google Video and YouTube: SlideShare rides the tidal wave of Flash-based applications that has swept through the web over the past few years. By achieving near-ubiquity with its plugin, Flash has become the gel capsule that makes rich media content easy to swallow across platform and browser (there’s a reason that the web video explosion happened when it did, the way it did). But in a sneaky way, this has changed the nature of our web browsers, transforming them into something that more resembles a highly customizable TV set. And by this I mean to point out that Flash inhibits the creative reuse of the materials being delivered since Flash-wrapped video (or slideshows) can’t, to my knowledge, be easily broken apart and remixed.

Where once the “view source” ethic of web browsers reigned, allowing you to retrieve the underlying html code of any page and repurpose all or parts of it on your own site, the web is becoming a network of congealed packages — bite-sized broadcast units that, while nearly effortless to disseminate through linking and embedding, are much less easily reworked or repurposed (unless the source files are made available). The proliferation of rich media and dynamic interfaces across the web is no doubt exciting, but it’s worth considering this darker side.

networking textbooks

Daniel Anderson (UNC Chapel Hill), an ever-insightful voice in the wise crowd around the Institute, just announced an exciting english composition textbook project that he’s about to begin developing with Prentice Hall. He calls it “Write Now.” Already the author of two literature textbooks, Dan has been talking with college publishers across the industry about the need to rethink both their process and their product, and has been pleasantly surprised to find a lot of open minds and ears:

…publishers are ready to push technology and social writing both in the production and distribution of their products and in the content of the texts. I proposed playlist, podcast, photo essay, collage, video collage, online profile, and dozens of other technology-based assignments for Write Now. Everyone I talked to welcomed those projects and wanted to keep the media and technology focus of the books. And, not one publisher balked at the notion of shifting the production model of the book to one consistent with the second Web. I proposed adding a public dimension to the writing through social software. I suggested participation from a broad community, and asked that publishers fund and facilitate that participation. I asked that some of the materials be released for the community to use and modify. We all had questions about logistics and boundaries, but every publisher was eager to implement these processes in the development of the books.

In fact, my eventual selection of Prentice Hall as a home for the project was based mainly on their eagerness to figure out together how we might transform the development process by opening it up. I started with an admission that I felt like I was straddling two worlds: one the open source, communal knowledge sphere I admire and participate with online, and two the world where I wanted to publish textbooks that challenge the state of writing but reach mainstream writing classes. We sat down and started brainstorming about how that might happen. The results will evolve over the next several years, but I wouldn’t have committed to the process if I didn’t believe it would offer opportunities for future students, for publishers, and for me to push writing.

As is implied above, Write Now will constitute a blend of the cathedral and the bazaar modes of authorship — Dan will be principal architect, but will also function as a moderator and coordinator of contributions from around the social web. Very exciting.

He also points to another fledgeling networked book project in the rhet/comp field, Rhetworks: An Introduction to the Study of Discursive Networks. I’m going to take some time to look this over.

google buys writely, or, the book is reading you, part 2

Last week Google bought Upstartle, a small company that created an online word processing program called Writely.  Writely is like a stripped-down Microsoft Word, with the crucial difference that it exists entirely online, allowing you to write, edit, publish and store documents (individually or in collaboration with others) on the network without being tied to any particular machine or copy of a program. This evidently confirms the much speculated-about Google office suite with Writely and Gmail as cornerstone, and presumably has Bill Gates shitting bricks .

Writely is like a stripped-down Microsoft Word, with the crucial difference that it exists entirely online, allowing you to write, edit, publish and store documents (individually or in collaboration with others) on the network without being tied to any particular machine or copy of a program. This evidently confirms the much speculated-about Google office suite with Writely and Gmail as cornerstone, and presumably has Bill Gates shitting bricks .

Back in January, I noted that Google requires you to be logged in with a Google ID to access full page views of copyrighted works in its Book Search service. Which gave me the eerie feeling that the books are reading us: capturing our clickstreams, keywords, zip codes even — and, of course, all the pages we’ve traversed. This isn’t necessarily a new thing. Amazon has been doing it for a while and has built a sophisticated personalized recommendation system out of it — a serendipity engine that makes up for some of the lost pleasures of browsing a physical store. There it seems fairly harmless, useful actually, though it depends on who you ask (my mother says it gives her the willies). Gmail is what has me spooked. The constant sprinkle of contextual ads in the margin attaching like barnacles to my bot-scoured correspondences. Google’s acquisition of Writely suggests that things will only get spookier.

I’ve been a webmail user for the past several years, and more recently a blogger (which is a sort of online word processing) but I’m uneasy about what the Writely-Google union portends — about moving the bulk of my creative output into a surveilled space where the actual content of what I’m working on becomes an asset of the private company that supplies the tools.

Imagine you’re writing your opus and ads, drawn from words and themes in your work, are popping up in the periphery. Or the program senses line breaks resembling verse, and you get solicited for publication — before you’ve even finished writing — in one of those suckers’ poetry anthologies.  Leave the cursor blinking too long on a blank page and it starts advertising cures for writers’ block. Copy from a copyrighted source and Writely orders you to cease and desist after matching your text in a unique character string database. Write an essay about terrorists and child pornographers and you find yourself flagged.

Leave the cursor blinking too long on a blank page and it starts advertising cures for writers’ block. Copy from a copyrighted source and Writely orders you to cease and desist after matching your text in a unique character string database. Write an essay about terrorists and child pornographers and you find yourself flagged.

Reading and writing migrated to the computer, and now the computer — all except the basic hardware — is migrating to the network. We here at the institute talk about this as the dawn of the networked book, and we have open source software in development that will enable the writing of this new sort of born-digital book (online word processing being just part of it). But in many cases, the networked book will live in an increasingly commercial context, tattooed and watermarked (like our clothing) with a dozen bubbly logos and scoured by a million mechanical eyes.

Suddenly, that smarmy little paper clip character always popping up in Microsoft Word doesn’t seem quite so bad. Annoying as he is, at least he has an off switch. And at least he’s not taking your words and throwing them back at you as advertisements — re-writing you, as it were. Forgive me if I sound a bit paranoid — I’m just trying to underscore the privacy issues. Like a frog in a pot of slowly heating water, we don’t really notice until it’s too late that things are rising to a boil. Then again, being highly adaptive creatures, we’ll more likely get accustomed to this softer standard of privacy and learn to withstand the heat — or simply not be bothered at all.

ESBNs and more thoughts on the end of cyberspace

Anyone who’s ever seen a book has seen ISBNs, or International Standard Book Numbers — that string of ten digits, right above the bar code, that uniquely identifies a given title. Now come ESBNs, or Electronic Standard Book Numbers, which you’d expect would be just like ISBNs, only for electronic books. And you’d be right, but only partly.  ESBNs, which just came into existence this year, uniquely identify not only an electronic title, but each individual copy, stream, or download of that title — little tracking devices that publishers can embed in their content. And not just books, but music, video or any other discrete media form — ESBNs are media-agnostic.

ESBNs, which just came into existence this year, uniquely identify not only an electronic title, but each individual copy, stream, or download of that title — little tracking devices that publishers can embed in their content. And not just books, but music, video or any other discrete media form — ESBNs are media-agnostic.

“It’s all part of the attempt to impose the restrictions of the physical on the digital, enforcing scarcity where there is none,” David Weinberger rightly observes. On the net, it’s not so much a matter of who has the book, but who is reading the book — who is at the book. It’s not a copy, it’s more like a place. But cyberspace blurs that distinction. As Alex Pang explains, cyberspace is still a place to which we must travel. Going there has become much easier and much faster, but we are still visitors, not natives. We begin and end in the physical world, at a concrete terminal.

When I snap shut my laptop, I disconnect. I am back in the world. And it is that instantaneous moment of travel, that light-speed jump, that has unleashed the reams and decibels of anguished debate over intellectual property in the digital era. A sort of conceptual jetlag. Culture shock. The travel metaphors begin to falter, but the point is that we are talking about things confused during travel from one world to another. Discombobulation.

This jetlag creates a schism in how we treat and consume media. When we’re connected to the net, we’re not concerned with copies we may or may not own. What matters is access to the material. The copy is immaterial. It’s here, there, and everywhere, as the poet said. But when you’re offline, physical possession of copies, digital or otherwise, becomes important again. If you don’t have it in your hand, or a local copy on your desktop then you cannot experience it. It’s as simple as that. ESBNs are a byproduct of this jetlag. They seek to carry the guarantees of the physical world like luggage into the virtual world of cyberspace.

But when that distinction is erased, when connection to the network becomes ubiquitous and constant (as is generally predicted), a pervasive layer over all private and public space, keeping pace with all our movements, then the idea of digital “copies” will be effectively dead. As will the idea of cyberspace. The virtual world and the actual world will be one.

For publishers and IP lawyers, this will simplify matters greatly. Take, for example, webmail. For the past few years, I have relied exclusively on webmail with no local client on my machine. This means that when I’m offline, I have no mail (unless I go to the trouble of making copies of individual messages or printouts). As a consequence, I’ve stopped thinking of my correspondence in terms of copies. I think of it in terms of being there, of being “on my email” — or not. Soon that will be the way I think of most, if not all, digital media — in terms of access and services, not copies.

But in terms of perception, the end of cyberspace is not so simple. When the last actual-to-virtual transport service officially shuts down — when the line between worlds is completely erased — we will still be left, as human beings, with a desire to travel to places beyond our immediate perception. As Sol Gaitan describes it in a brilliant comment to yesterday’s “end of cyberspace” post:

In the West, the desire to blur the line, the need to access the “other side,” took artists to try opium, absinth, kef, and peyote. The symbolists crossed the line and brought back dada, surrealism, and other manifestations of worlds that until then had been held at bay but that were all there. The virtual is part of the actual, “we, or objects acting on our behalf are online all the time.” Never though of that in such terms, but it’s true, and very exciting. It potentially enriches my reality. As with a book, contents become alive through the reader/user, otherwise the book is a dead, or dormant, object. So, my e-mail, the blogs I read, the Web, are online all the time, but it’s through me that they become concrete, a perceived reality. Yes, we read differently because texts grow, move, and evolve, while we are away and “the object” is closed. But, we still need to read them. Esse rerum est percipi.

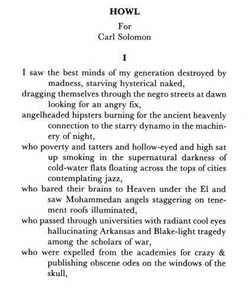

Just the other night I saw a fantastic performance of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl that took the poem — which I’d always found alluring but ultimately remote on the page — and, through the conjury of five actors, made it concrete, a perceived reality. I dug Ginsburg’s words. I downloaded them, as if across time. I was in cyberspace, but with sweat and pheremones. The Beats, too, sought sublimity — transport to a virtual world. So, too, did the cyberpunks in the net’s early days. So, too, did early Christian monastics, an analogy that Pang draws:

Just the other night I saw a fantastic performance of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl that took the poem — which I’d always found alluring but ultimately remote on the page — and, through the conjury of five actors, made it concrete, a perceived reality. I dug Ginsburg’s words. I downloaded them, as if across time. I was in cyberspace, but with sweat and pheremones. The Beats, too, sought sublimity — transport to a virtual world. So, too, did the cyberpunks in the net’s early days. So, too, did early Christian monastics, an analogy that Pang draws:

…cyberspace expresses a desire to transcend the world; Web 2.0 is about engaging with it. The early inhabitants of cyberspace were like the early Church monastics, who sought to serve God by going into the desert and escaping the temptations and distractions of the world and the flesh. The vision of Web 2.0, in contrast, is more Franciscan: one of engagement with and improvement of the world, not escape from it.

The end of cyberspace may mean the fusion of real and virtual worlds, another layer of a massively mediated existence. And this raises many questions about what is real and how, or if, that matters. But the end of cyberspace, despite all the sweeping gospel of Web 2.0, continuous computing, urban computing etc., also signals the beginning of something terribly mundane. Networks of fiber and digits are still human networks, prone to corruption and virtue alike. A virtual environment is still a natural environment. The extraordinary, in time, becomes ordinary. And undoubtedly we will still search for lines to cross.

end of cyberspace

The End of Cyberspace is a brand-new blog by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, former academic editor and print-to-digital overseer at Encyclopedia Britannica, and currently a research director at the Institute for the Future (no relation). Pang has been toying with this idea of the end of cyberspace for several years now, but just last week he set up this blog as “a public research notebook” where he can begin working through things more systematically. To what precise end, I’m not certain.

The end of cyberspace refers to the the blurring, or outright erasure, of the line between the virtual and the actual world. With the proliferation of mobile devices that are always online, along with increasingly sophisticated social software and “Web 2.0” applications, we are moving steadily away from a conception of the virtual — of cyberspace — as a place one accesses exclusively through a computer console. Pang explains:

Our experience of interacting with digital information is changing. We’re moving to a world in which we (or objects acting on our behalf) are online all the time, everywhere.

Designers and computer scientists are also trying hard to create a new generation of devices and interfaces that don’t monopolize our attention, but ride on the edges of our awareness. We’ll no longer have to choose between cyberspace and the world; we’ll constantly access the first while being fully part of the second.

Because of this, the idea of cyberspace as separate from the real world will collapse.

If the future of the book, defined broadly, is about the book in the context of the network, then certainly we must examine how the network exists in relation to the world, and on what terms we engage with it. I’m not sure cyberspace has ever really been a home for the book, but it has, in a very short time, totally altered the way we read. Now, gradually, we return to the world. But changed. This could get interesting.

hmmm… online word processing

Not quite sure what I think of this new web-based word processor, Writely. Cute Web 2.0ish name, “beta” to the hilt. It’s free and quite easy to get started. I guess it falls into that weird zone of transitional unease between desktop computing and the wide open web, where more and more of our identity and information resides. Some of the tech specifics: Writely saves documents in Word and (as of today) Open Office formats, outputs as RSS and to some blogging platforms (not ours), and can also be saved as a simple web page (here’s the Writely version of this post). A key feature is that Writely documents can be written and edited by multiple authors, like SubEthaEdit only totally net-based. It feels more or less like a disembodied text editor for a wiki.

I’m trying to think about what’s different about writing online. Movable Type, our blogging software, is essentially an ultra-stripped-down text editor — web-based — and it’s no fun to work in. That’s partly because the text field is about the size of a mail slot, but writing online can be annoying for other reasons, chief among them the fact that you have to be online to work, and second that you are susceptible to the chance mishaps of the browser (accidentally backing up and losing everything, it crashes, you forgot to pay Time Warner and they turn off the web etc.). But with a conventional word processor you’re vulnerable to the mishaps of the machine (hard drive dies and you didn’t back it up, it crashes and you didn’t save, coffee spills…). Writely saves everything automatically as you go, maintaining a revision history and tracking changes — a very nice feature.

They say this is the future of software, at least for the simple everyday kind of stuff: web-based tool suites and tons of online data storage. I guess it’s nice not having to be tied to one machine. Your work is just out there, waiting for you to log in. But then again, your work is just out there…

nicholas carr on “the amorality of web 2.0”

Nicholas Carr, who writes about business and technology and formerly was an editor of the Harvard Business Review, has published an interesting though problematic piece on “the amorality of web 2.0”. I was drawn to the piece because it seemed to be questioning the giddy optimism surrounding “web 2.0”, specifically Kevin Kelly’s rapturous late-summer retrospective on ten years of the world wide web, from Netscape IPO to now. While he does poke some much-needed holes in the carnival floats, Carr fails to adequately address the new media practices on their own terms and ends up bashing Wikipedia with some highly selective quotes.

Carr is skeptical that the collectivist paradigms of the web can lead to the creation of high-quality, authoritative work (encyclopedias, journalism etc.). Forced to choose, he’d take the professionals over the amateurs. But put this way it’s a Hobson’s choice. Flawed as it is, Wikipedia is in its infancy and is probably not going away. Whereas the future of Britannica is less sure. And it’s not just amateurs that are participating in new forms of discourse (take as an example the new law faculty blog at U. Chicago). Anyway, here’s Carr:

The Internet is changing the economics of creative work – or, to put it more broadly, the economics of culture – and it’s doing it in a way that may well restrict rather than expand our choices. Wikipedia might be a pale shadow of the Britannica, but because it’s created by amateurs rather than professionals, it’s free. And free trumps quality all the time. So what happens to those poor saps who write encyclopedias for a living? They wither and die. The same thing happens when blogs and other free on-line content go up against old-fashioned newspapers and magazines. Of course the mainstream media sees the blogosphere as a competitor. It is a competitor. And, given the economics of the competition, it may well turn out to be a superior competitor. The layoffs we’ve recently seen at major newspapers may just be the beginning, and those layoffs should be cause not for self-satisfied snickering but for despair. Implicit in the ecstatic visions of Web 2.0 is the hegemony of the amateur. I for one can’t imagine anything more frightening.

He then has a nice follow-up in which he republishes a letter from an administrator at Wikipedia, which responds to the above.

Encyclopedia Britannica is an amazing work. It’s of consistent high quality, it’s one of the great books in the English language and it’s doomed. Brilliant but pricey has difficulty competing economically with free and apparently adequate….

…So if we want a good encyclopedia in ten years, it’s going to have to be a good Wikipedia. So those who care about getting a good encyclopedia are going to have to work out how to make Wikipedia better, or there won’t be anything.

Let’s discuss.

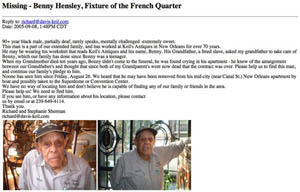

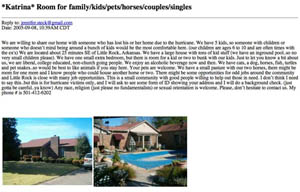

craigslist new orleans – web 2.0 in action

You can find just about anything on craigslist. Bikes, mattresses, futons, stereos, landscapers, moving vans, graphic designers, jobs. You can even find missing persons, or a safe haven thousands of miles from what was once your home. How a public classifieds section transformed itself overnight into a dynamic networked survival book – a central node in the effort to locate the missing and provide shelter to the uprooted – captures the significance of what has happened over the past two weeks in Katrina’s wake. The web has been pushed to its full potential, capturing both the enormity of the disaster (in a way that the professional media, working alone, would have been unable to), and the details – the individual lives, the specific intersections of streets – that got swept up in the flood. This give-and-take between global and “hyperlocal” is what Web 2.0 is all about. Danah Boyd recently described this as “glocalization” – “a dance between the individual and the collective”:

In business, glocalization usually refers to a sort of internationalization where a global product is adapted to fit the local norms of a particular region. Yet, in the social sciences, the term is often used to describe an active process where there’s an ongoing negotiation between the local and the global (not simply a directed settling point). In other words, there is a global influence that is altered by local culture and re-inserted into the global in a constant cycle. Think of it as a complex tango with information constantly flowing between the global and the local, altered at each junction.

The diverse, simultaneous efforts on the web to bear witness and bring relief to the ravaged Gulf Coast – a Knight Ridder newspaper running hyperlocal blogs out of a hurricane bunker (nola.com); a frantic text message sent from a phone in a rapidly flooding attic to relatives in Idaho who, in turn, post precise coordinates for rescue on a missing persons forum (anecdote from Craig Newmark of craigslist); an apartment rental registry turned into a disaster relief housing index; images from consumer digital cameras leading the network news; scipionus.com, the interactive map wiki where users can post specific, geographically situated information about missing persons and flood levels – that is the dance. The case of the scrappy craigslist, or rather its users, rising to the occasion is particularly moving.