More fun with book metadata. Hot on the heels of Bkkeepr comes Booklert, an app that lets you keep track of the Amazon rank of your (or anyone else’s) book. Writer, thinker and social media maven Russell Davies speculated that he’d love to have such a thing for keeping track of his book. No sooner was this said than MCQN had built it; so far it has few users, but fairly well-connected ones.

Reading MCQN’s explanation I get a picture of Booklert as a time-saving tool for hypercompetitive and stat-obsessed writers, or possibly as a kind of masochistic entertainment for publishers morbidly addicted to seeing their industry flounder. Then perhaps I’m being uncharitable: assuming you accept the (deeply dodgy) premise that the only meaningful book sales are those conducted through Amazon, Booklert – or something similar – could be used to create personalized bestseller lists, adding a layer of market data to the work of trusted reviewers and curators. I’d be interested to find out which were the top-selling titles in the rest of the Institute’s personal favourites list; I’d also be interested to find out what effect a few weeks’ endorsement by a high-flying member of the digerati might have on a handful of books.

But whether or not it is, as Davies asserts, “exactly the sort of thing a major book business could have thought of, should have thought of, but didn’t”, Booklert illustrates the extent to which, in the context of the Web, most of the key developments around the future of the book do not concern the form, purposes or delivery mechanism of the book. They concern metadata: how it is collected, who owns it, who can make use of it. Whether you’re talking DRM, digitization, archiving, folksonomies or feeds, the Web brings a tendency – because an ability – to see the world less in terms of static content than in terms of dynamic patterns, flows and aggregated masses of user-generated behavior. When thus measured as units in a dynamic system, what the books themselves actually contain is only of secondary importance. What does this say about the future of serious culture in the world of information visualization?

Category Archives: Web2.0

trade-offs

Alex Itin just cross-posted a wonderful new piece on his blog, and Vimeo.

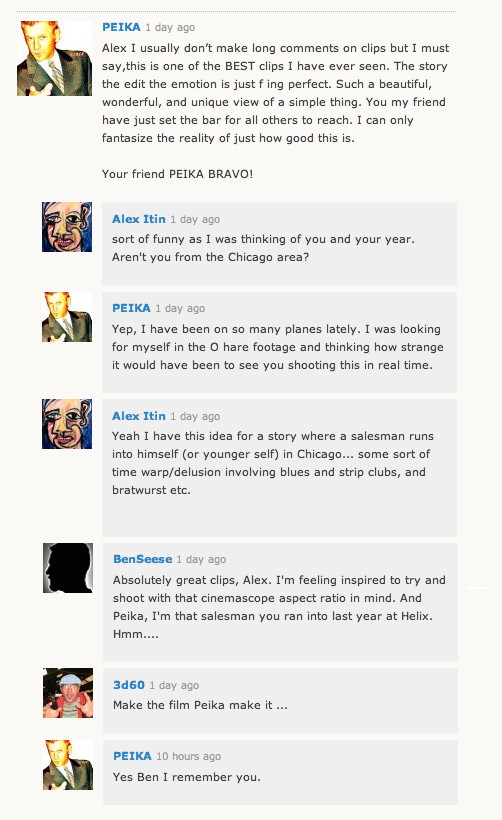

I watched it on Vimeo and was struck by the terrific back and forth discussion between Alex and the people who are looking at his work. It’s gone beyond “cool video dude” and “you rock” to include rather thoughtful sharing of feelings and riffs on ideas for new work. By engaging with his “readers” in the way that he is, Alex is building a community around his work. He is inventing a new medium and unconsciously taking on the role of “author in a networked environment” that we talk about so often on these pages.

Check out this exchange on Vimeo about the video:

I am struck by the compromise Alex has to make as an artist in order to build a community around his work. When we first met, Alex was making brilliant multi-modal works combining his paintings, video and audio mash-ups. While on the one hand he had complete control over how the elements appeared and combined it was done in proprietary software which created standalone documents which seriously limited the size of his potential audience. In 2005 he became the institute’s first artist in residence and we made a blog for him where he started posting a continuous stream of individual works. Moving onto the web provided a much larger audience, but the blog format meant that he lost the ability to make complex layered works. Alex’s big web breakthrough came when he started to post his paintings to Flickr and his videos to Vimeo. This allowed him to begin a dialog with his audience and even to begin a series of exciting collaborations with other artists. But at the expense of having to put his paintings on one site and his videos on another.

The balkanization of art works (video here, photos there, and audio in yet another space) in the web 2.0 environment is frustrating, but i completely understand why it’s better to show your work in a place which fosters a dynamic and lively back and forth. I look forward to the day when artists won’t have to make a trade-off between form/content and community.

Sophie 1.0 is being released next week and Alex is the first artist we’re giving it to. Sophie documents don’t display in a web page (yet) but they do have an online component which enables people to have a conversation about the work in the “margin” of the work itself. Stay tuned, we’ll put an announcement up here of Alex’s first Sophie.

critical perspectives on web 2.0

First Monday has a new special issue out devoted to unpacking the politics, economics and ethics of Web 2.0. Looks like lots of interesting stuff. From the preface by Michael Zimmer:

Web 2.0 represents a blurring of the boundaries between Web users and producers, consumption and participation, authority and amateurism, play and work, data and the network, reality and virtuality. The rhetoric surrounding Web 2.0 infrastructures presents certain cultural claims about media, identity, and technology. It suggests that everyone can and should use new Internet technologies to organize and share information, to interact within communities, and to express oneself. It promises to empower creativity, to democratize media production, and to celebrate the individual while also relishing the power of collaboration and social networks.

But Web 2.0 also embodies a set of unintended consequences, including the increased flow of personal information across networks, the diffusion of one’s identity across fractured spaces, the emergence of powerful tools for peer surveillance, the exploitation of free labor for commercial gain, and the fear of increased corporatization of online social and collaborative spaces and outputs.

In Technopoly, Neil Postman warned that we tend to be “surrounded by the wondrous effects of machines and are encouraged to ignore the ideas embedded in them. Which means we become blind to the ideological meaning of our technologies” [1]. As the power and ubiquity of Web 2.0 rises, it becomes increasingly difficult for users to recognize its externalities, and easier to take the design of such tools simply “at interface value” [2]. Heeding Postman and Turkle’s warnings, this collection of articles will work to remove the blinders of the unintended consequences of Web 2.0’s blurring of boundaries and critically explore the social, political, and ethical dimensions of Web 2.0.

amazon reviewer no. 7 and the ambiguities of web 2.0

Slate takes a look at Grady Harp, Amazon’s no. 7-ranked book reviewer, and finds the amateur-driven literary culture there to be a much grayer area than expected:

Absent the institutional standards that govern (however notionally) professional journalists, Web 2.0 stakes its credibility on the transparency of users’ motives and their freedom from top-down interference. Amazon, for example, describes its Top Reviewers as “clear-eyed critics [who] provide their fellow shoppers with helpful, honest, tell-it-like-it-is product information.” But beneath the just-us-folks rhetoric lurks an unresolved tension between transparency and opacity; in this respect, Amazon exemplifies the ambiguities of Web 2.0. The Top 10 List promises interactivity – ?”How do I become a Top Reviewer?” – ?yet Amazon guards its rankings algorithms closely…. As in any numbers game (tax returns, elections) opacity abets manipulation.

no longer separated by a common language

LibraryThing now interfaces with the British Library and loads of other UK sources:

The BL is a catch in more than one way. It’s huge, of course. But, unlike some other sources, BL data isn’t normally available to the public. To get it, our friends at Talis, the UK-based library software company, have granted us special access to their Talis Base product, an elephantine mass of book data. In the case of the BL, that’s some twelve million unique records, two copies Gutenberg Bibles and two copies of the Magna Carta.

content syndicate

While Andrew Keen laments the decline of professionalised content production, and Publishing2.0 fuels the debate about whether there’s a distinction between ‘citizen journalism’ and the old-fashioned sort, I’ve spent the morning at Seedcamp talking with a Dubai-based entrepreur who’s blurring the distinction even further.

Content Syndicate is a distributed marketplace for buying, selling and commissioning content (By that they mean writing). Submitted content is quality-assessed first automatically and then by human editors, and can be translated by the company staff if required. They’ve grown since starting a year or so ago to 30 staff and a decent turnover.

This enterprise interests me because it picks up on some recurring themes around the the changes digitisation brings to what a writer is, and what he or she does. In some respects, this system commodifies content to an extent traditionalists will find horrifying – what writer, starting out (as many do) wanting to change the world, will feel happy having their work fed through a semiautomatic system in which they are a ‘content producer’? But while it may be helping to dismantle – in practice – the distinction between professional and amateur writers, and thus risking helping us towards Keen’s much-lamented mulch of unprofessionalised blah, but at least people are getting paid for their efforts. And you can rebut this last fear of unprofessionalised blah by saying that at least there’s some quality control going on. (The nature of the quality control is interesting too, as it’s a hybrid of automated assessment and human idiot-checking; this bears some thinking about as we consider the future of the book.)

So this enterprise points towards some ways in which we’re learning to manage, filter and also monetise this world of increasingly-pervasive ‘content everywhere’, and suggests some of the realities in which writers increasingly work. I’ll be interested to see how we adapt to this: will the erstwhile privileged position of ‘writers’ give way as these become mere grunts producing ‘content’ for the maw of the market? Or will some subtler and more nuanced bottom-up hierarchy of writing excellence emerge?

books and the man i sing

I’ve been reading failed Web1.0 entrepreneur Andrew Keen’s The Cult of the Amateur. For those who haven’t hurled it out of the window already, this is a vitriolic denouncement of the ways in which Web2.0 technology is supplanting ‘expert’ cultural agents with poor-quality ‘amateur’ content, and how this is destroying our culture.

In vehemence (if, perhaps, not in eloquence), Keen’s philippic reminded me of Alexander Pope (1688-1744). Pope was one of the first writers to popularize the notion of a ‘critic’ – and also, significantly, one of the first to make an independent living through sales of his own copyrighted works. There are some intriguing similarities in their complaints.

In the Dunciad Variorum (1738), a lengthy poem responding to the recent print boom with parodies of poor writers, information overload and a babble of voices (sound familiar, anyone?) Pope writes of ‘Martinus Scriblerus’, the supposed author of the work

He lived in those days, when (after providence had permitted the Invention of Printing as a scourge for the Sins of the learned) Paper also became so cheap, and printers so numerous, that a deluge of authors cover’d the land: Whereby not only the peace of the honest unwriting subject was daily molested, but unmerciful demands were made of his applause, yea of his money, by such as would neither earn the one, or deserve the other.

The shattered ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’, lamented by Pope in the eighteenth century when faced with a boom in printed words, is echoed by Keen when he complains that “the Web2.0 gives us is an infinitely fragmented culture in which we are hopelessly lost as to how to focus our attention and spend our limited time.” Bemoaning our gullibility, Keen wants us to return to an imagined prelapsarian state in which we dutifully consume work that has been as “professionally selected, edited and published”.

In Keen’s ideal, this selection, editing and publication ought (one presumes) to left in the hands of ‘proper’ critics – whose aesthetic in many ways still owes much to (to name but a few) Pope’s Essay On Criticism (1711), or the satirical work The Art of Sinking In Poetry (1727). But faith in these critics is collapsing. Instead, new tools that enable books to be linked give us “a hypertextual confusion of unedited, unreadable rubbish”, while publish-on-demand services swamp us in “a tidal wave of amateurish work”.

So what? you might ask. So the first explosion in the volume of published text created some of the same anxieties as this current one. But this isn’t a narrative of relentless evolutionary progress towards a utopia where everything is written, linked and searchable. The two events don’t exist on a linear trajectory; the links between Pope’s critical writings and Keen’s Canute-like protest against Web2.0 are more complex than that.

Pope’s response to the print boom was not simply to wish things could return to their previous state; rather, he popularized a critical vocabulary that both helped others to deal with it, and also – conveniently – positioned himself at the tip of the writerly hierarchy. His extensive critical writings, promoting the notions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ quality writing and lambasting the less talented, served to position Pope himself as an expert. It is no coincidence that he was one of the first writers to break free of the literary patronage model and make a living out of selling his published works. The print boom that he critiqued so scatologically was the same boom that helped him to the economic independence that enabled him to criticize as he saw fit.

But where Pope’s approach to the print boom was critical engagement, Keen offers only nostalgic blustering. Where Pope was crucial in developing a language with which to deal with the print boom, Keen wishes only to preserve Pope’s approach. So, while you can choose to read the two voices, some three centuries apart, as part of a linear evolution, it’s also possible to see them as bookends (ahem) to the beginning and end of a literary era.

This era is characterized by a conceptual and practical nexus that shackles together copyright, authorship and a homogenized discourse (or ‘common high culture’, as Keen has it), delivers it through top-down and semi-monopolistic channels, and proposes always a hierarchy therein whilst tending ever more towards proliferating mass culture. In this ecology, copyright, elitism and mass populism form inseparable aspects of the same activity: publications and, by extension, writers, all busy ‘molesting’ the ‘peace of the honest unwriting subject’ with competing demands on ‘his applause, yea [on] his money’.

The grading of writing by quality – the invention of a ‘high culture’ not merely determined by whichever ruler chose to praise a piece – is inextricable from the birth of the literary marketplace, new opportunities as a writer to turn oneself into a brand. In a word, the notion of ‘high culture’ is intimately bound up in the until-recently-uncontested economics of survival as a writer.

Again, so what? Well, if Keen is right and the new Web2.0 is undermining ‘high culture’, it is interesting to speculate whether this is the case because it is undermining writers’ established business model, or whether the business model is suffering because the ‘high’ concept is tottering. Either way, if Keen should be lambasted for anything it is not his puerile prose style, or for taking a stand against the often queasy techno-utopianism of some of Web2.0’s champions, but because he has, to date, demonstrated little of Pope’s nous in positioning himself to take advantage of the new economics of publishing.

Others have been more wily, though, in working out exactly what these economics might be. While researching this piece, I emailed Chris Anderson, Wired editor, Long Tail author, sometime sparring partner for Keen and vocal proponent of new, post-digital business models for writers. He told me that

“For what I do speaking is about 10x more lucrative than selling books […]. For me, it would make sense to give away the book to market my personal appearances, much as bands give away their music on MySpace to market their concerts. Thus the title of my next book, FREE, which we will try to give away in every way possible.”

Thus, for Anderson, there is life beyond copyright. It just doesn’t work the same way. And while Keen claims that Web2.0 is turning us into “a nation so digitally fragmented it’s no longer capable of informed debate” – or, in other words, that we have abandoned shared discourse and the respected authorities that arbitrate it in favor of a mulch of cultural white noise, it’s worth noting that Anderson is an example of an authority that has emerged from within this white noise. And who is making a decent living as such.

Anderson did acknowledge, though, that this might not apply to every kind of writer – “it’s just that my particular speaking niche is much in demand these days”. Anderson’s approach is all very well for ‘Big Ideas’ writers; but what, one wonders, is a poet supposed to do? A playwright? My previous post gives an example of just such a writer, though Doctorow’s podcast touches only briefly on the economics of fiction in a free-distribution model. I’ve argued elsewhere that ‘fiction’ is a complex concept and severely in need of a rethink in the context of the Web; my hunch is that while for nonfiction writers the Web requires an adjustment of distribution channels and little more, or creative work – stories – the implications are much more drastic.

I have this suspicion that, for poets and storytellers, the price of leaving copyright behind is that ‘high art’ goes with it. And, further, that perhaps that’s not as terrible as the Keens of this world might think. But that’s another article.

feeling random

Following HarperCollins’ recent Web renovations, Random House today unveiled their publisher-driven alternative to Google: a new, full-text search engine of over 5,000 new and backlist books including browsable samples of select titles. The most interesting thing here is that book samples can be syndicated on other websites through a page-flipping browser widget (Flash 9 required) that you embed with a bit of cut-and-paste code (like a YouTube clip). It’s a nice little tool, though it comes in two sizes only — one that’s too small to read, and one that embedded would take up most of a web page (plus it keeps crashing my browser). Compare below with HarperCollins’ simpler embeddable book link:

Worth noting here is that both the search engine and the sampling widget were produced by Random House in-house. Too many digital forays by major publishers are accomplished by hiring an external Web shop, meaning of course that little ends up being learned within the institution. It’s an old mantra of Bob’s that publishers’ digital budgets would be better spent by throwing 20 grand at a bright young editor or assistant editor a few years out of college and charging them with the task of doing something interesting than by pouring huge sums into elaborate revampings from the outside. Random House’s recent home improvements were almost certainly more expensive, and more focused on infrastructure and marketing than on genuinely reinventing books, but they indicate a do it yourself approach that could, maybe, lead in new directions.

video (in your own words)

is the slogan of Mojiti, a company based in Beijing which has enabled commenting for video. Users can annotate any video on YouTube, Google, MySpace and about twenty other providers with text, shape and images. the annotations can be animated as well. The interface for making comments is unusually simple and straightforward. On first glance this is an important step forward in web 2.0 applications. [note: the demos all show text fields with solid backgrounds obscuring the video. in fact it’s quite easy to make the text box transparent or to turn off the annotations at any point to see the unalloyed video]

terrain as browsing mechanism

Ben’s post last week, book as terrain, about converting any image to an interactive map with hotspots contained a link to a blog which collects info about all sorts of google map mashups. Ben’s post was about using book pages as geographic jumping-off points. However, as i read the endlessly fascinating list of other sorts of mashups it occurred to me that in addition to “book as terrain” we could also look at the idea of “Google map mashups” as a genuinely new form of expression. As I read through the wonderfully annotated list I realized that they cover the full gamut of subjects you would find in a bookstore . . . . Fiction, Non-Fiction, Travel, History, Sports, Games, Religion, Personal Growth, and Crime.

It’s interesting to realize that as our experience moves relentlessly into the virtual domain, that geography, which in the past was firmly rooted in the “real,” increasingly becomes the mechanism for organizing our activiites in virtual space.