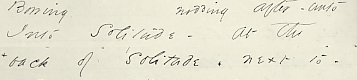

Emily Dickinson’s poems weren’t published during her lifetime- it was only after her death that her sister found Emily’s manuscripts, tucked at the bottom of a trunk, and decided to publish them. In the translation from manuscript to printed page, many aspects of her poems were lost. In editor’s notes, scholars admit to getting snagged on her unusual punctuation, capitalization, and line breaks. The biggest stumbling block comes with Dickinson’s endnotes. For many poems in her manuscripts, Dickinson provided alternate lines. Sometimes only an adjective changed but at other times entire stanzas morphed. In “How the Old Mountains drip with Sunset” (291), Dickinson couldn’t decide upon a single preposition, so there became six ways that one could be in relation to Solitude.

I’ve been building a Sophie book, which pulls Dickinson’s alternate lines into the body of the poem. I’ve been trying to make the lines no longer seem like potential-yet-never-permanent afterthoughts. When the line is presented within the text of the poem, I find it receives more consideration (if not equal weight, at least more screen time). Plus, in most publications, editors make the decision which lines to incorporate and which ones to discard. With this version, the reader gets pulled into that discussion, closer to Dickinson’s original work. When there is an alternate line, the reader can press on a black button and scroll through Dickinson’s suggested changes:

Now, when reading “When we stand on the tops of Things” (242), the reader can see what effect it has when “they bear their dauntless/fearful/tranquil heads.” In the book, the reader begins to encounter questions that surface frequently in literary translation, the question of “what is best in context of the poem.” However, I think that another type of issue is happening here with Dickinson’s work. In “Many a phrase has the English Language” (276), Dickinson waits, tucked in her bedroom in Amherst, for a phrase to arrive with its thundering prospective. The line can read: a) till I grope, and weep; b) till I stir, and weep; or c) till I start, and weep. Each single phrase is fine. But I prefer to think of Emily Dickinson thrashing in her sleigh bed, groping, stirring, and starting all at once. A certain open playfulness becomes built into the framework of the poem once you can let all the possibilities toggle by in one reading experience.

In terms of timing, it pleased me to see Judith Thurman’s recent New Yorker article “Her Own Society.” Thurman describes Dickinson’s dashes as moments in which she “evaded the necessity of putting a period to their mystery—or to her own.” And, earlier this summer, Dan gave me Susan Howe’s “My Emily Dickinson” to read. At one point, Howe argues that Dickinson built a new poetic form grounded in hesitation. I liked that idea of hesitation, circling back and reconsidering what you might say, what you could possibly. For “I prayed at first, a little Girl” (576), Dickinson gives two final stanzas. The two aren’t that unlike. However, looping back, you notice that they accomplish markedly unique things.

Till I could take the Balance

That tips so frequent now,

It takes me all the while to poise —

And then — it does’nt stay —Till I could catch my Balance

That slips so easy, now,

It takes me all the while to poise —

It isn’t steady tho’.

At this point in the project, I’m afraid I’ve sunken too deep into semi-obsessive adoration to begin to see how this Sophie book could be useful. With this blog post, I’d like to open up the concept for discussion. How do you think a collection like this could be used? Is it ultimately helpful?

Download it here

Right click to download the file. Unzip the file to open the folder. Open “ED Ten” in Sophie Reader.