Preface

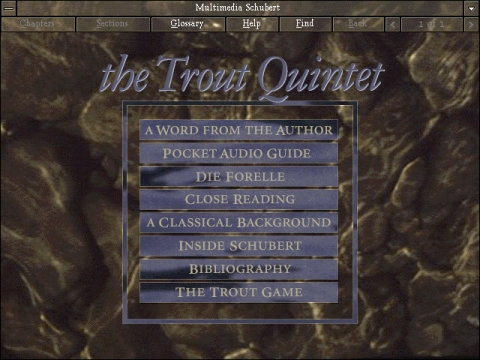

I’ve been exploring the potential of “new media” for nearly thirty years. There was an important aha moment early on when I was trying to understand the essential nature of books as a medium. The breakthrough came when i stopped thinking about the physical form or content of books and focused instead on how they are used. At that time print was unique compared to other media, in terms of giving its users complete control of the sequence and pace at which they accessed the contents. The ability to re-read a paragraph until it’s understood, to flip back and forth almost instantly between passages, to stop and write in the margins, or just think - this affordance of reflection (in a relatively inexpensive portable package) was the key to understanding why books have been such a powerful vehicle for moving ideas across space and time. I started calling books user-driven media - in contrast to movies, radio, and television, which at the time were producer-driven. Once microprocessors were integrated into audio and video devices, I reasoned, this distinction would disappear. However – and this is crucial – back in 1981 I also reasoned that its permanence was another important defining aspect of a book. The book of the future would be just like the book of the past, except that it might contain audio and video on its frozen “pages.” This was the videodisc/cdrom era of electronic publishing.

The emergence of the web turned this vision of the book of the future as a solid, albeit multimedia object completely upside down and inside out. Multimedia is engaging, especially in a format that encourages reflection, but locating discourse inside of a dynamic network promises even more profound changes Reading and writing have always been social activities, but that fact tends to be obscured by the medium of print. We grew up with images of the solitary reader curled up in a chair or under a tree and the writer alone in his garret. The most important thing my colleagues and I have learned during our experiments with networked books over the past few years is that as discourse moves off the page onto the network, the social aspects are revealed in sometimes startling clarity. These exchanges move from background to foreground, a transition that has dramatic implications.

So…

I haven’t published anything for nearly twelve years because, frankly, I didn’t have a model that made any sense to me. One day when I was walking around the streets of London I suddenly I realized I did have a model. I jokingly labeled my little conceptual breakthrough “a unified field theory of publishing,” but the more I think about it, the more apt that sounds, because getting here has involved understanding how a number of different aspects both compliment and contradict each other to make up a dynamic whole. I’m excited about this because for the first time the whole hangs together for me. I hope it will for you too. if not, please say where the model breaks, or which parts need deepening, fixing or wholesale reconsideration.

key questions a unified field theory has to answer:

- What are the characteristics of a successful author in the era of the digital network?

- Ditto for readers: how do you account for the range of behaviors that comprise reading in the era of the digital network?

- What is the role of the publisher and the editor?

- What is the relationship between the professional (author) and the amateur (reader)?

- Do the answers to 1-4 afford a viable economic model?

so how exactly did i get here?

I was thinking about Who Built America, a 1993 Voyager cd-rom based on a wonderful 2-volume history originally published by Knopf. In a lively back and forth with the book’s authors over the course of a year, we tried to understand the potential of an electronic edition. Our conceptual breakthrough came when we started thinking about process – that a history book represents a synthesis of an author’s reading of original source documents, the works of other historians and conversations with colleagues. So we added hundreds of historical documents – text, pictures, audio, video – to the cd-rom edition, woven into dozens of “excursions” distributed throughout the text. Our hope was to engage readers with the author’s conclusions at a deeper, more satisfying level. That day in London, as I thought about how this might occur in the context of a dynamic network (rather than a frozen cd-rom), there seemed to be an explosion of new possibilities. Here are just a few:

- Access to source documents can be much more extensive free of the size, space and copyright constraints of cd-rom

- Dynamic comment fields enable classes to have their unique editions, where a lively conversation can take place in the margins.

- A continuously evolving text, as the authors add new findings in their work and engage in back and forth with “readers” who have begun to learn history by “doing history”, and have begun both to question the authors’ conclusions and to suggest new sources and alternative syntheses. Bingo! That last one leads to . . . .

b) Hmmm. On the surface that sounds a lot like a Wikipedia article, in the sense that it’s always in process and consideration of the the back and forth is crucial to making sense of the whole. However it’s also different, because a defining aspect of the Wikipedia is that once an article is started, there is no special, ongoing role accorded to the the person who initiated it or tends it over time. And that’s definitely not what I’m talking about here. Locating discourse in a dynamic network doesn’t erase the distinction between authors and readers, but it significantly flattens the traditional perceived hierarchy. Ever since we published Ken Wark’s Gamer Theory I’ve tended to think of the author of a networked book as a leader of a group effort, similar in many respects to the role of a professor in a seminar. The professor has presumably set the topic and likely knows more about it than the other participants, but her role is to lead the group in a combined effort to synthesize and extend knowledge. This is not to suggest that one size will fit all authors, especially during this period of experimentation and transition. Some authors will want to lay down a completed text for discussion; others may want to put up drafts in the anticipation of substantial re-writing based on reader input. Other “authors’ may be more comfortable setting the terms and boundaries of the subject and allowing others to participate directly in the writing . . . .

The key element running through all these possibilities is the author’s commitment to engage directly with readers. If the print author’s commitment has been to engage with a particular subject matter on behalf of her readers, in the era of the network that shifts to a commitment to engage with readers in the context of a particular subject.

c) As networked books evolve, readers will increasingly see themselves as participants in a social process. As with authors, especially in what is likely to be a long transitional period, we will see many levels of (reader) engagement – from the simple acknowledgement of the presence of others presence to very active engagement with authors and fellow readers..

(an anecdotal report regarding reading in the networked era)

A mother in London recently described her ten-year old boy’s reading behavior: “He’ll be reading a (printed) book. He’ll put the book down and go to the book’s website. Then, he’ll check what other readers are writing in the forums, and maybe leave a message himself, then return to the book. He’ll put the book down again and google a query that’s occurred to him.” I’d like to suggest that we change our description of reading to include the full range of these activities, not just time spent looking at the printed page.

continuing…

d) One thing i particularly like about this view of the author is that it resolves the professional/amateur contradiction. It doesn’t suggest a flat equality between all potential participants; on the contrary it acknowledges that the author brings an accepted expertise in the subject AND the willingness/ability to work with the community that gathers around. Readers will not have to take on direct responsibility for the integrity of the content (as they do in wikipedia); hopefully they will provide oversight through their comments and participation, but the model can absorb a broad range of reader abilities and commitment

e) Once we acknowledge the possibility of a flatter hierarchy that displaces the writer from the center or from the top of the food chain and moves the reader into a space of parallel importance and consideration -? i.e. once we acknowledge the intrinsic relationship between reading and writing as equally crucial elements of the same equation -? we can begin to redefine the roles of publisher and editor. An old-style formulation might be that publishers and editors serve the packaging and distribution of authors’ ideas. A new formulation might be that publishers and editors contribute to building a community that involves an author and a group of readers who are exploring a subject.

f) So it turns out that far from becoming obsolete, publishers and editors in the networked era have a crucial role to play. The editor of the future is increasingly a producer, a role that includes signing up projects and overseeing all elements of production and distribution, and that of course includes building and nurturing communities of various demographics, size, and shape. Successful publishers will build brands around curatorial and community building know-how AND be really good at designing and developing the robust technical infrastructures that underlie a complex range of user experiences. [I know I’m using “publisher” to encompass an array of tasks and responsibilities, but I don’t think the short-hand does too much damage to the discussion].

g) Once there are roles for author/reader/editor/publisher, we can begin to assess who adds what kind of value, and when. From there we can begin to develop a business model. My sense is that this transitional period (5, 10, 50 years) will encompass a variety of monetizing schemes. People will buy subscriptions to works, to publishers, or to channels that aggregate works from different publishers. People might purchase access to specific titles for specific periods of time. We might see tiered access, where something is free in “read-only” form, but publishers charge for the links that take you OUT of the document or INTO the community. Smart experimenting and careful listening to users/readers/authors will be very important.

h) The ideas above seem to apply equally well to all genres -? whether textbooks, history, self-help, cookbooks, business or fiction – particularly as the model expands to include the more complex arena of interactive narrative. [Think complex and densely textured online events/games whose authors create worlds in which readers play a role in creating the ongoing narrative, rather than choose- your-own ending stories.]

This is not to say that one size will fit all. For example, different subjects or genres will have different optimal community paradigms – e.g. a real-time multi-player game vs. close readings of historical or philosophical essays. Even within a single genre, it will make a difference whether the community consists of students in the same class or of real-world strangers.

other thoughts/questions

- Authors should be able to choose the level of moderation/participation at which they want to engage; ditto for readers.

- It’s not necessary for ALL projects to take this continuous/never-finished form.

- This applies to all modes of expression, not just text-based. The main distinction of this new model is not type of media but the mechanism of distribution. Something is published when the individual reader/user/viewer determines the timing and mode of interaction with the content and the community Something is broadcast when it’s distributed to an audience simultaneously and in real-time. Eventually, presumably, only LIVE content will be broadcast.

- When talking about some of these ideas with people, quite often the most passionate response is that “surely, you are not talking about fiction.” If by fiction we mean the four-hundred page novel then the answer is no, but in the long term arc of change i am imagining, novels will not continue to be the dominant form of fiction. My bet now is that to understand where fiction is going we should look at what’s happening with “video games.” World of Warcraft is an online game with ten million subscribers paying $15 per month to assemble themselves into guilds (teams) of thirty or more people who work together to accomplish the tasks and goals which make up the never-ending game. It’s not a big leap to think of the person who developed the game as an author whose art is conceiving, designing and building a virtual world in which players (readers) don’t merely watch or read the narrative as it unfolds – they construct it as they play. Indeed, from this perspective, extending the narrative is the essence of the game play.

- As active participants in this space, the millions of player/readers do not merely watch or read the unfolding narrative, they are constructing it as they play.

- Editors should have the option of using relatively generic publishing templates for projects whose authors, for one reason or another, do not justify the expense of building a custom site. I can even imagine giving authors access to authoring environments where they can write first drafts or publish experimentally.

- A corollary of the foregrounding of the social relations of reading and writing is that we are going to see the emergence of celebrity editors and readers who are valued for their contributions to a work.

- Over time we are also likely to see the emergence of “professional readers” whose work consistus of tagging our digitized culture (not just new content, but everything that’s been digitized and in all media types . . . . books, video, audio, graphics). This is not meant to undervalue the role of d.elicious and other tagging schemes or the combined wisdom of the undifferentiated crowd but just a recognition of the likelihood that over time the complexity of the task of filtering the web will give rise to a new job category.

- As this model develops, the way in which readers can comment/contribute/interact needs to evolve continuously in order to allow ever more complex conversations among ever more people.

- How does re-mix fit in? as a mode of expression for authors? as something that readers do? as something that other people are allowed to do with someone’s else’s material?

- It’s important to design sites that are outward-looking, emphasizing the fact that boundaries with the rest of the net are porous.

- Books can have momentum, not in the current sense of position on a best-seller or Amazon list, but rather in the size and activity-level of their communities.

- Books can be imagined as channels, especially when they “gather” other books around them. Consider, for example, the Communist Manifesto or the Bible as core works that inspire endless other works and commentary – a constellation of conversations.

- Successful publishers will develop and/or embrace new ways of visualizing content and the resulting conversations. [e.g. imagine google searches that make visible not just the interconnections between hits but also how the content of each hit relates to the rest of the document and/or discipline it’s part of… NOTE: this is an example of imagining something we can’t do yet, but that informs the way we design/invent the future]

- In the videodisc/cd-rom phase of electronic publishing we explored the value and potential of integrating all media types in a new multi-medium which afforded reflection. With the rise of the net we began exploring the possibilities of what happens when you locate discourse in a dynamic network. A whole host of bandwidth and hardware issues made the internet unfriendly to multimedia but those limitations are coming to an end. it’s now possible to imagine weaving the strands back together. (perhaps this last point makes this even more of a unified field theory)