We’ve got a small NEH grant to hold a couple of brainstorming sessions. the overarching goal of the sessions is to come up with a conceptual framework for learning spaces which combine the rich media attributes of the cd-rom era with the collaborative affordances of the net. Here’s a short excerpt from the grant application:

With the advent of the cd-rom in the late 80s, a few pioneering humanities scholars began to develop a new vocabulary for multi-layered, multi-modal digital publications. Since that time, the internet has emerged as a powerful engine for collaboration across peer networks, radically collapsing the distance between authors and readers and creating new communal spaces for work and review.

To date, these two evolutionary streams have been largely separate. Rich multimedia is still largely consigned to individual consumption on the desktop, while networked collaboration generally occurs around predominantly textual media such as the blogosphere, or bite-sized fragments on YouTube and elsewhere. We propose to carry out initial planning for two ambitious digital publishing projects that will merge these streams into powerfully integrated experiences.

Although the locus of scholarly discourse is slowly but clearly moving from bound/printed pages to networked screens, we’ve yet to reach the tipping point. The printed book is still the gold standard of the academy. The goal of these projects is to produce born-digital works that are as elegant as printed books and also draw on the power of audio and video illustrations and new models of community-based inquiry -? and do all of these so well that they inspire a generation of young scholars with the promise of digital scholarship.

We’re going to hold three meetings grouped by discipline -? History, Music and Media Studies.

Consider this an invitation to apply to be part of one of these sessions. If you think you can make a significant contribution to the discussion, please send us a note. Or if you know someone else who would be perfect, please pass the word on to them.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Sophie demo movies now available

In addition to the demo books themselves, we’ve posted several movies demonstrating the capabilities of Sophie 1.0. At about a minute each, these clips provide a cursory glance at a variety of our books, complete with hopefully unobtrusive narration by yours truly.

[1] Candyman — A digital edition of John Gibbs’s “Candyman” essay, originally published by Wallflower Press.

[2] Cookbooks — Librarian and avid cookbook collector Kim Beeman shares some of her favorite rarities.

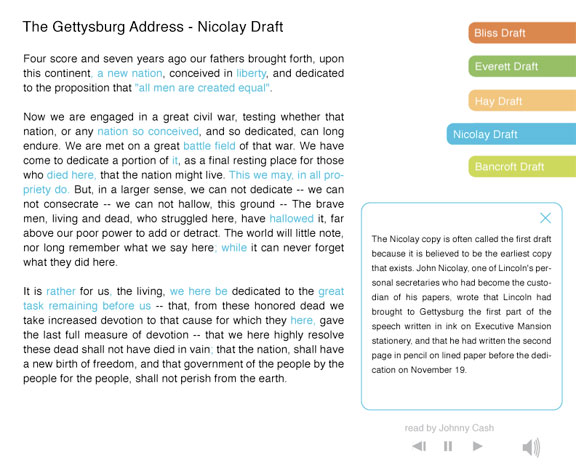

[3] Gettysburg Address — As Holladay wrote earlier this month, this is a multimodal presentation of the Address’s five drafts.

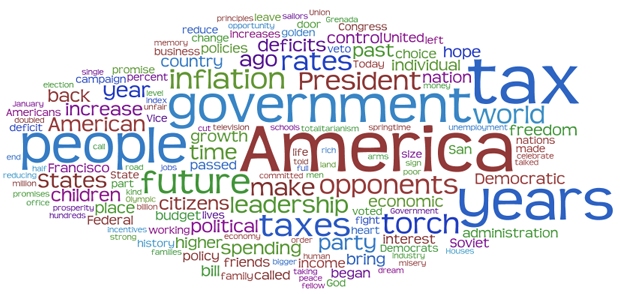

[4] Nomination Speech Visualizations — Also mentioned in a previous if:book post, this book combines worldle.net visualizations with transcripts and audio recordings of presidential nomination speeches.

[5] Robert Winter’s Mozart — A close reading of Mozart’s Dissonant Quartet, ported from a popular Voyager CD-ROM with new features.

We welcome any and all feedback.

Greenblatt on human agency and New Historicism

Image via Queen’s University.

Here is a little bit about the MIT communications forum on October 14, with respondent David Thorburn, moderator Diana Henderson, and lecturer Stephen Greenblatt. Greenblatt is the Cogen University Professor of Humanities at Harvard. He co-founded the literary journal Representations and wrote the book Will in the World; he edits Norton Anthology of Literature and the Norton Shakespeare.

David Thorburn began the lecture by asking Greenblatt about an historical moment: his time as an undergrad- and graduate student at Yale on the cusp of New Criticism. Greenblatt listed his teachers, among them Harold Bloom, Jeffrey Hartman, and Robert Penn Warren. While New Criticism was the principle game in town, there was “something else stirring” in continuity with it. While defining New Criticism for his audience, Greenblatt referenced the W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley line, “Judging a poem is like judging a pudding or a machine. One demands that it work.” A poem was to be examined like a beautifully wrought object, or a verbal icon. Greenblatt recounted the feeling of empowerment New Criticism initially gave him: freeing him from a certain kind of “time-wasting and sociology,” and liberation from “a certain cult and taste.” You had to know how to “get your hands dirty, and learn what internal structures were.” And though he broke away from this school of thought, he said he is grateful to have experience with it.

Thorburn added that Greenblatt has the power of reading closely, even if he doesn’t read closely in the same way his mentors did; he still reads with “the rigor and excitement of the old New Critics.” Henderson added that this historical moment is an excellent time for criticism, since “attention to detail and method is very important with a glut of information.”

As for the “something else stirring,” Greenblatt said his thinking was affected by a “huge dose of Cambridge,” which was “curiously, not part of the New Criticism at Yale.” There he played a game where texts were passed around on scraps of paper and everyone in the room was supposed to guess when each text was written. It “seemed unbelievably stupid at the time,” but Greenblatt concluded that it was important to understand how a text fit into a specific historical and sociological moment. After a “mega-dose” of this, he came to understand the importance of thinking inside a text, rather than removing the text from its context (as in New Criticism).

Henderson concurred that delving together into the historical moment fosters a generosity of relationship between students and professors, a dialogue and openness “that allows you to not take umbrage,” and allows for “a kind of listening to student voices” instead of professors serving as “a kind of acolyte” and the students just taking notes.

Henderson said to Greenblatt, “Yours was a friendlier face of incorporating American and English thought at a moment of real culture wars.” [She was referring to the difference between New Historicism (a term Greenblatt himself coined for examining a text within the framework of history, culture, and sociology) and Cultural Materialism, a term for a branch of literary criticism stemming from Marxism that looks at a text not as an object, but as a process that is both politicized and historigraphical.]

Greenblatt defined a pivotal moment in his intellectual life: he read Althusser in the ’70s, especially the union of theory and practice, which opened his mind to how one could think differently of culture and society. This was a “brilliant continuation of hermeutic thought and New Criticism,” which worked to align what he thought he’d learned with what was (then) going on in France.

Thorburn quoted Greenblatt back to himself, saying, “This is what was going on when I found my voice.” Thorburn asked Greenblatt to expand upon this statement.

Greenblatt said that it was clear in his writing, in his style, that he was not an apprentice any longer. “Things holding you [down] disappear: you’re not worrying what your advisor thinks.” Instead Greenblatt began to wonder, How could I think out of the model of an individual life?

He wrote a book about Sir Walter Raleigh, which he explained was about this. Raleigh was a soldier, explorer, scoundrel, courier, an interesting poet. He was not simply defined by his work as a fiction writer or a critic or a professor. Greenblatt pondered Raleigh and himself, what their identities were, what their subjectivities were. He asked, “What would it mean not to think so conventionally about a life? What would it mean for me to have a voice?” He felt “liberation to think in a life, passionately, his life and my life… not to throw one away and not think about the other one, but not to be stuck in the biographical model of an individual life.”

Henderson added that the great question, then, was how to use history to tell a story. At the moment that New Historicism emerged, it put the individual back into the system (as opposed to high theory and Cultural Materialism). It was about America in individual lives.

Greenblatt agreed, “It was a great moment, an unbelievable moment… the question was how to sound like who you are.”

Henderson said, “And that’s where history comes into play: in who YOU are. It is a unit of rhetoric, organizing history, you sort of grab something that for you resonates and tells a vivid story… of course, [grabbing one story and not another] immediately begs the question, why not this one instead?”

Greenblatt proceeded with a vivid story of his own: when he finished his Raleigh book, he sent the manuscript to Oxford University Press. There a woman named Agnes Latham, who had worked all her life studying Raleigh (the culmination of which was a single article). She read his work and suggested that after 20-25 years perhaps Greenblatt would know enough about Raleigh to write about Raleigh. “That vision of how to do this work, to know absolutely every detail about someone’s life… seemed to me a form of intellectual deadening.” He remembered a professor who wrote on Hardy, who was afraid of publishing in case he discovered something else about Hardy. As a scholar, Greenblatt advised, decide when you have to cut yourself off; later you may know more but won’t end up saying much more. You have to know when to stop. He said he had to learn for himself and his students to be responsible, but not to be so obsessive or so frightened. You must shape around the idea that you have a story to tell, for yourself and your readers.

Thornburn reiterated that there are a few key terms in New Historicism that are problematic and central in Greenblatt’s work: human agency and self-fashioning. He asked Greenblatt to elaborate on these.

Human agency and self-fashioning are terms “like fate and free will: the more general they are, the gassier they are.” Greenblatt responded with an anecdote from a trip to Israel: he traveled to give a lecture, and on Friday night, someone invited him to have dinner at their house in the old city. After dinner, they sat on the roof under the stars and sang the Hebrew prayers traditionally sung after meals. Greenblatt doesn’t think of himself as having much of a spiritual life – his exact term for his perception of Jewish tradition was “total flapdoodle” – but he had a powerful semitic reaction to this. He said being Jewish in this scenario was about non-agency; it was uncontrollable, like getting an erection at the beach. There was something about “the words that you sing as a child, that you don’t believe in… I was already way post-belief, but still affected.” And yes, agency became a part of it – he felt the urge to ask, “Christ, what’s that about, and what am I going to do about it?” He said, “I didn’t know what to do with it; I was amazed by it.” All Saturday afternoon, with sounds of helicopters overhead, he thought about how to parse his experience. He chose not to ignore it, and met a friend at the PLO to talk it through; in this moment he chose agency over the alternative. He spent a lot of time trying to think who he was, what historical situation he was in, and why these things made him want to meet at the PLO instead of going elsewhere, instead of being swung around on a string, “and that’s what I’ve been interested in all my life.”

Thorburn added here that one of Greenblatt’s strengths is “this dividedness in him.”

Henderson expanded upon Greenblatt’s example, pointing out that we must identify local choices, the effect of those choices and what difference they make, and finally, “how do we tell our own story and the history of the world in a way we think matters.” We must consider the value of our storytelling, and “our obligation to whatever It out there is.” Henderson said it seemed to her that only half of it is agency.

She then brought up the subject of this lecture, the place of the book today, and posited, “Can we consider the place of the book today?” Greenblatt interjected, who are we to consider the place of the book today? Henderson said considering the students in front of her, “And as scholars, what are we asking of our young now? We’ve gone to another extreme because we’re trying to get things out NOW? In another system that doesn’t want to publish your book.” This sense of immediacy seemed out of place to Henderson in the current publishing world.

Greenblatt continued to say that last year Harvard passed a vote that faculty would be required if they wrote an article to allow access to a digital version for Harvard, so that all their scholarly work would be universally accessible digitally. “As a general principle, the idea that the work that we do should have value digitally and have universal access,” is what Greenblatt said he had been calling for for years. In an article for the MLA, he said we must transform our understanding of what it means to appear on the web and how we can use that. We must make more broadly accessible our work. We must feel that work is significant; though the web must take into consideration the feeling of community that is subscription-based. You feel you are part of a community when you subscribe to a scholarly journal. But ultimately your work can reach a larger scholarly audience with the internet.

A grad student with blonde dreadlocks asked a question about Jane Newman, pastoral conventions, and bringing history back as an objective field. Greenblatt replied, “I don’t carry a card in my wallet that says Official New Historicist. On the whole… making old and new historicism live again… it does very good archival work, sociological work, has very little relation to [objectivity.]”

The example he put forth is whether Shakespeare was Catholic. “I just think the work is not pious… I think it’s actually quite secular.” It is “manifest in a lifelong grappling with Christianity and Catholicism.” In Greenblatt’s opinion, Shakespeare had an interesting engagement with religion, but there is inadequate evidence to support either theory. One can examine Shakespeare’s father’s will, his mother’s relationship to the Arden family in Birmingham, and the people who educated Shakespeare. “Can I prove anything? No. But I thought it was interesting to tease out [these elements.]” Another example: Was Donne tormented all his life? Greenblatt says he thinks Donne is definitely interested in “damaged institutional goods,” and he drew upon the aesthetics all his life because he probably had personal relations to them, but we don’t know whether he actually had personal relations to them or not.

A man in the audience inquired about the state of culture. Greenblatt responded, What if, for example, Nomads or exchange or exile were actually the “normal state” of culture, rather than that of settled cultures? What follows from that? What if we think about cultures in movement? Greenblatt wanted to try to think about a new set of terms – e.g. culture is essentially about movement. Or, Greenblatt insisted, this could go in a second direction: the weakening of the boundaries between art-making and criticism. In one’s pedagogical practice, this means getting more interested in relation to the makers. Academics are in the habit, Greenblatt said, to refuse absolutely everything the makers say – not only what they’re up to, but their relation to art-making (this stubbornness is consistent with Greenblatt’s assertion that professors’ work is driven by students even though one doesn’t admit it). With new technology, it’s possible to make things in interesting ways – certainly visual things – that couldn’t have been made five years ago, certainly not 20 years ago.

For example, Greenblatt said, look what Shakespeare did with his citations: he was famous as a thief. “What happens when he steals from other people, what does he do with the materials? What happens if you don’t imagine that the fate of all these objects was to fall into Shakespeare and end there? They don’t end there.” Henderson agreed. They have metamorphic effects. Greenblatt is interested in experimenting with that idea intellectually, aesthetically, and in following moving cultures from place to place.

Henderson added that the materials do not end with Shakespeare, because Shakespeare is being performed and reimagined all of the time. Performing Shakespeare made people in the humanities aware again that they need to talk to the makers.

An older man on the stairs asked for Greenblatt’s take on Israel.

Greenblatt responded to an issue that is specific to Harvard. In his opinion, John Pullman said things that were extremely foolish to say. Therefore Greenblatt thought that though many people didn’t want him to, he should come as a poet to Harvard and people should give him a hard time. Rescinding the invitation seemed foolish, but protest seemed appropriate (and wouldn’t require the university to support the West Bank Settlements).

A man in the audience asked if there are moments in scholarship that are like the security gates at airports, that you can go in but can’t go back out. He gave the Greeks vs. the Romans as an example.

Greenblatt said he would love to say that groups in conflict will just work things out, but that this is untrue. Catholics and Protestants, for example, are two factions that couldn’t “settle it.” Epicurianism, which is Greek organization, survives because a Roman poet wrote a fantastic poem that survived, and in the Middle Ages, was found. “My sense is that there’s no getting back to the thing itself. But to give up the dream completely – that all we have is what the clerks have given us – is a depressing historical position. All my life… gives me the illusion that I’m finally getting it.”

Greenblatt launched into a description of Richard Madox’s diary. His recounting of the book went something like this: Madox wanted to go on “an insane voyage to the new world.” But he quickly realized “he hated every sucker on the ship.” Madox was a very finely educated, rather sophisticated guy, and he was stuck on board with “a bunch of horrible yahoos.” So in his diary, he gave them Latin and Greek names, and invented his own code to complain about them freely. Madox died off the coast of Brazil, and the others brought his diary back because they didn’t know what was in it. When Greenblatt read this book, he felt he was finally reading “a voice that hadn’t been mediated in fifty thousand ways.” It wasn’t the product of German Romanticism.

A woman asked Greenblatt to reflect upon Amitad Ghosh’s In An Antique Land. Greenblatt replied that the book is an important touchstone, it articulates problems, but literal travel isn’t recorded in a book. Even the digital world of literature doesn’t solve this problem. Literal travel is a crucial element, he continued – who are the customs agents, what do you have to pay, what do you have to conceal? There is a huge amount of material of this kind. And that literal travel becomes the metaphorical. (He is now in his classes at Harvard incorporating a simulation of that sort of travel with digital resources. One such course is “Travel and Transformation in the Early 17th Century.”) In a play like King Lear, Greenblatt said, you have “a crazy pastiche of things”: Isaiah plus Sir Philip Sydney mixed up with Machiavelli. Each carries with a it a set of implications through its (physical) travels.

A woman in the audience asked for Greenblatt’s take on the “what if,” or the imagination, and also to discuss the relationship between hypothetical and historical in his work.

Greenblatt employed the example of Natalie Zemon Davis’s Fiction in the Archives, which allowed for people to think about why people were writing the things they were writing instead of concentrating on the truth contained therein. Greenblatt argued that there is an extent of imagination and making up already implicit in the materials that we use. We are saturated with “crazy conjectures” of people who left traces of themselves. It is even more difficult to work with fictional materials, which are full of imaginary conjectures. You must account for the fact that you are deploying imagination yourself as you study it.

“On the other hand,” Greenblatt said, “You can’t just make it all up.” For example, one could use the discourse, “I never thought of anything I wrote as ‘fiction,’ ” but I am interested in effect and affects that are reachable through the imagination to get them in play. “You cough when the story is over if you’re not using the imagination.” In Anthony Burgess’s Nothing Like the Sun, though, there is a difference in the game being played. There is a tiny hook of documentary evidence to begin delving into the story. As a reader, perhaps it’s best to assume Shakespeare made up from stuff he could draw on from his life, not one character he is trying to portray from his life. This is better described as something else, like literary biography.

Henderson concluded, “Doesn’t it just come back to, What did Shakespeare say, anyway?”

Greenblatt laughed, “He’s a wonderful broken field runner; you can’t catch him that way anyway.”

Thorburn handed Greenblatt a copy of a book he published 25 years ago. Greenblatt read aloud the introduction, a story of a man on an airplane who asked Greenblatt to read the words, ‘I want to die, I want to die.’ The point of this fragment is that Greenblatt chooses the moments in his life when he recites someone else’s words. (Ironically, Thorburn had chosen this moment for him.)

Greenblatt ended the talk by saying, If you could record every movement of every atom as the world was constructed, it would become clear there was no free will, but it would also be clear that “one atom swerved.” That swerve was ridiculed for decades – it was written in 1417 by Lucretius. Now it is “the only thing in contemporary physics that seems kind of hip.” In other words, generations of theologians ridiculed the thing that saved agency.

nine curiosities from the beeman cookbook collection

This Sophie book showcases several interesting, rare, or otherwise odd cookbooks from the collection of Kimberly Beeman. You can download it here (.zip, 60Mb). Make sure that you have Sophie or Sophie Reader installed.

The title page, including a video introduction.

A detail page, with additional close-up shots of the cookbook, as well as a video description.

the five drafts of the gettysburg address: a sophie book

Contrary to popular lore, Lincoln did not write the Gettysburg Address on the back of an envelope. Though given short notice that he was to speak at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, he had enough time to write two drafts of the address prior to November 19th, 1863. These he entrusted to his private secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay. The remaining three drafts were written well after the delivery of the address for inclusion in various charitable anthologies. Each draft differs slightly in wording and punctuation, most likely because each was written from memory.

This Sophie book compares the differences in the five drafts visually, provides information about the provenance of each draft, and features a reading of the address by Johnny Cash.

You can download it here. (.zip, 2.9 Mb) Make sure that you have Sophie or Sophie Reader installed.

By clicking on the title of the draft at the top of the text, the differences in wording will be highlighted, and information about the particular draft is displayed.

meanwhile . . . .

My colleagues at the Institute and i are busy making some interesting things with Sophie 1.0. We’re going to start posting them on a new institute website devoted to Sophie 1.0. [They will also be available on the OpenSophie site]

and the first document is . . . .

An Experiment in Visualization: Presidential Nomination Acceptance Speeches from Truman through Obama and McCain.

In addition to the wordle.net visualizations in which the size of the word is proportionate to the number of times it is used, we’ve also included an audio recording and the full text for each speech. In order to encourage reader’s to look closely at each speech, you don’t see the name of the speaker until you decide to click on the word cloud to reveal it. Is that Reagan? Perhaps Clinton? it’s very interesting trying to parse the differences and what they mean. Although there are still problems with the way that Sophie’s comment streams are managed, we’ve enabled them here. Please if you leave comments for others, make them serious and not simply . . . .”testing” or “gee i wonder how this works.” You can download it here. But before you do, make sure you download and install the Sophie Reader.

Mellon announces a $1.25 million grant for Sophie 2.0

Last week the Mellon Foundation announced a $1.25 million grant to the University of Southern California for a java-based version of Sophie, which will be known as Sophie 2.0. In addition to improving on Sophie 1.0 in various ways, Sophie 2.0 documents will run inside the browser. The programming team is committed to working in the open as much as possible, so expect public releases of the code beginning in late November of this year. Sophie 2.0 itself is scheduled for release in September 2009, and yes, there will be a conversion path for Sophie 1.0 documents.

How do you want to read?

(Photo of Tom Stoppard’s book case, made by T. Anthony, via The New York Times.)

For the sake of travel and convenience, sure, even a Kindle is better than toting a book shelf with you on an airplane. But people still resist eReaders. Is it because eReaders cannot meet your reading needs, or because they’re unaffordable and inelegant?

The media is brimming with iPhone and Android apps and speculations about eReading. Even literary blogs are tech-focused: Maud Newton dropped her iPhone in the subway, but didn’t lose her place in her virtual book. And Chad W. Post ties up last week’s “end of publishing” coverage with highlights from New York Magazine‘s comments (most of them are much more positive about eBooks than New York Magazine).

eReading devices haven’t made an Android-esque debut, but they’re chugging forward. Forbes presents a $850 iRex reader with a 10.2 inch screen. Plastic Logic has produced a one-pound, flexible eReader without Wi-Fi or backlighting (it looks sort of like one of those plastic covers Calvin put over his “Bats Are Bugs” report in the Calvin and Hobbes cartoon). The phones still have a leg up on these devices because they have names and color screens and do not cost $850.

The Sony eReader has been said to be difficult to navigate. [Edit: the new one has just been released.] The Kindle is distracting. And the iRex has received criticism from USA Today for a short battery life, slow loading, and incompatibility with Windows. In other words, eReaders exist but no model has achieved ubiquitousness; those that have managed to draw an audience are still clunky, slow, and don’t have enough memory for major personal libraries. Until we all start to feel tech-lust, let’s ignore these beasts and discuss something more important.

How do you take your eBooks? You can turn pages in Scribd’s “Opening Up Education,” or scroll down through Hewson’s newA Season for the Dead. You can also scroll through scores of poetry at BlazeVox or Cory Doctorow’s new book, Content. You can read Warren Ellis’s comics online each week, or pay for them to be printed on dead trees. Do you want to read books in blogs embedded by Google, or perhaps on your iPhone? Here are a few questions:

1) Is it more convenient in a pocket-sized device like one of these phones, a Kindle-sized screen, an iRex-sized screen, or a desktop screen? Are you inclined to stick with paperback-sized pages when you read an eBook?

2) Are there certain types of books you would read on one screen rather than another? I assume there are – do you use The Pynchon Test or some other method to determine the best possible reading device for your material?

3) Are there certain features in one of these that really works for you? Specifically, do you care about turning the pages? Scrolling? Reading inside or outside a browser?

4) Do you feel more compelled to buy a digital book if it is scarce? Libraries seem to be wondering whether to loan one ebook out at a time, or take advantage of the infinite resources the digital world provides.

5) Is the problem that screens are too closely associated with your workplace, and that you’re afraid of your reading being interrupted by popups, email, etc.?

6) Most importantly: Is there some mysterious intangible thing that books have and eBooks don’t? If so, can you describe it? (That library smell and your great-grandfather’s marginalia in your prized first-edition don’t count.)

There has been a little buzz about this this week, and I’d like to challenge if:Book readers to contribute to the dialogue.

Bob recently mentioned that he is puzzled as to why people are willing to have music on iPods and movies on their laptops, but feel skeptical of books on a screen. His point was that these other events are very social; one hears music at concerts and sees movies in theaters, but reading is the most solitary of these events and seems the easiest to move from paper to eReader. Dan Visel has posted on the beauty of the “pause” button. “Pause” converted films – which one cannot control in a theater – into something the user could control thoroughly. And it seems to me that perhaps we are resistant to converting to a user-driven form when the form we have is already user-driven. But if it were done well, would you read it?

I read an article this morning that suggested eBook culture would provide publication space for things that don’t deserve to be published, but if talented publishers are able to aggregate eBooks, we may be able to worry less about this problem (it would also benefit the publishing industry as a whole to cut down production costs, and would potentially provide for “risky” decisions – supporting new literary writers, for example, or books of short stories).

So lifting our heads above all these doubts: Is it a control issue, a content issue, or an aesthetic one? Or something larger about the way we connect to digital literature?

How do you connect to literature today? And how could you better engage with it?

The Golden Notebook Project – Readers Announced

Beginning November 10th, seven women will begin a public conversation in the margins of Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. The text of the novel and the readers’ conversation will be in a nifty new format designed by Apt Studios in London, similar to, but much more elegant than CommentPress. We’ll put up a preview sometime in October. In the meantime here is a brief bio of the seven readers:

Naomi Alderman grew up in London and attended Oxford University and UEA. Her first novel, Disobedience, was published in nine languages; it was read on BBC radio’s Book at Bedtime and won the Orange Award for New Writers. In 2007, she was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year, and one of Waterstones’ 25 Writers for the Future. From 2004 to 2007 Naomi was lead writer on the award-winning alternate reality game Perplex City and in 2008 she wrote the Alice in Storyland game for Penguin’s online We Tell Stories project.

Naomi Alderman grew up in London and attended Oxford University and UEA. Her first novel, Disobedience, was published in nine languages; it was read on BBC radio’s Book at Bedtime and won the Orange Award for New Writers. In 2007, she was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year, and one of Waterstones’ 25 Writers for the Future. From 2004 to 2007 Naomi was lead writer on the award-winning alternate reality game Perplex City and in 2008 she wrote the Alice in Storyland game for Penguin’s online We Tell Stories project.

Nona Willis Aronowitz is a freelance writer originally from New York City. She is a political and cultural critic who writes about sex, women, youth culture, and music for numerous publications including The Nation, The New York Observer, The Village Voice, VenusZine, and Salon.com. She currently co-writes a blog called GIRLdrive, the content of which will be in an upcoming book of the same name. GIRLdrive is based on a road trip taken across the United States in order to find out what young women think and feel about feminism, and will be published by Seal Press in Fall 2009. She lives in Chicago.

Nona Willis Aronowitz is a freelance writer originally from New York City. She is a political and cultural critic who writes about sex, women, youth culture, and music for numerous publications including The Nation, The New York Observer, The Village Voice, VenusZine, and Salon.com. She currently co-writes a blog called GIRLdrive, the content of which will be in an upcoming book of the same name. GIRLdrive is based on a road trip taken across the United States in order to find out what young women think and feel about feminism, and will be published by Seal Press in Fall 2009. She lives in Chicago.

Laura Kipnis is a cultural critic and theorist whose most recent books are Against Love: A Polemic and The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability (both from Pantheon); her essays have appeared in Slate, Harper’s, Playboy, the Nation, and The New York Times Magazine. Her work has been translated into thirteen languages; she’s received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and Yaddo; and she teaches in the Radio-TV-Film Department at Northwestern University (she is a former video artist). Her next book is called How To Become a Scandal.

Philippa Levine grew up in an upwardly-mobile, left-wing, working-class family in London. She received her doctorate in history during the Thatcher era when academic jobs were thin on the ground so after a brief stint teaching at the University of East Anglia, she took a post-doctoral fellowship in women’s studies in Australia where she combined academic work with radio broadcasting. In 1987 she moved to the US where she has lived since. Her publications include The British Empire, Sunrise to Sunset (2007), Gender and Empire: Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series (2004) Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (2003). Her current projects include a study of colonial nakedness, and of evolution, eugenics and empire.

Philippa Levine grew up in an upwardly-mobile, left-wing, working-class family in London. She received her doctorate in history during the Thatcher era when academic jobs were thin on the ground so after a brief stint teaching at the University of East Anglia, she took a post-doctoral fellowship in women’s studies in Australia where she combined academic work with radio broadcasting. In 1987 she moved to the US where she has lived since. Her publications include The British Empire, Sunrise to Sunset (2007), Gender and Empire: Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series (2004) Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (2003). Her current projects include a study of colonial nakedness, and of evolution, eugenics and empire.

Lenelle Moïse is an award-winning “culturally hyphenated pomosexual poet,” playwright and performance artist. She writes jazz-infused, politically-charged performance texts about Haitian-American culture and the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality. Moïse blogs regularly for Showtime’s OurChart.com. At 20, she co-wrote the screenplay for a Rodrigo Bellot film, Sexual Dependency, which has been screened at dozens of international festivals. Moïse received an MFA in Playwriting from Smith College. Moïse regularly performs her autobiographical one-woman show Womb-Words Thirsting at colleges across the United States and her newest musical Expatriate was produced Off-Broadway at the Culture Project in July 2008 and met with critical acclaim.

Lenelle Moïse is an award-winning “culturally hyphenated pomosexual poet,” playwright and performance artist. She writes jazz-infused, politically-charged performance texts about Haitian-American culture and the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality. Moïse blogs regularly for Showtime’s OurChart.com. At 20, she co-wrote the screenplay for a Rodrigo Bellot film, Sexual Dependency, which has been screened at dozens of international festivals. Moïse received an MFA in Playwriting from Smith College. Moïse regularly performs her autobiographical one-woman show Womb-Words Thirsting at colleges across the United States and her newest musical Expatriate was produced Off-Broadway at the Culture Project in July 2008 and met with critical acclaim.

Helen Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria in 1984 and raised in London. Her first novel, The Icarus Girl, is about a young girl and her imaginary friend. Her second novel, The Opposite House, is a nominee for the 2008 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Her third novel, White is for Witching, will be published in 2009.

Helen Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria in 1984 and raised in London. Her first novel, The Icarus Girl, is about a young girl and her imaginary friend. Her second novel, The Opposite House, is a nominee for the 2008 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. Her third novel, White is for Witching, will be published in 2009.

Harriet Rubin is best known as the author of The Princessa: Machiavelli for Women, a little bullet of a book on power that is now in its twelfth paperback printing. The book has been published in 27 languages and has been a bestseller in several of them. Rubin currently writes for The NY Times and other publications. She was the founder and publisher of Currency Books/Doubleday, which changed the science and soul of economic thinking. In late Fall 2008, she is launching an on-line publishing program devoted to business, power and leadership.

Harriet Rubin is best known as the author of The Princessa: Machiavelli for Women, a little bullet of a book on power that is now in its twelfth paperback printing. The book has been published in 27 languages and has been a bestseller in several of them. Rubin currently writes for The NY Times and other publications. She was the founder and publisher of Currency Books/Doubleday, which changed the science and soul of economic thinking. In late Fall 2008, she is launching an on-line publishing program devoted to business, power and leadership.