this is cross-posted from Bookfutures, the blog of Chris Meade, the director of IF:Book London

IF:BOOK ANNOUNCES ITS FIRST FICTIONAL STIMULUS

At last an end to those bored bookgroup blues!

You love books but are interested if sceptical about what ebooks, iPhones and laptops might do for literature? Re-ignite your passion for reading this summer – make sure you get if:book’s FICTIONAL STIMULUS, an amazing experience in digital reading which will be delivered to you by email, download, webpages and post in six segments and added extra bits.

EXPERIENCE THE STORIES OF TOMORROW TODAY!

Presented by novelist Kate Pullinger, including new writing by Cory Doctorow, Naomi Alderman, Kate Pullinger and poetry from Jacob Polley, Daljit Nagra, Eva Salzman plus new media renderings of classics by Rudyard Kipling, Williams Blake, Shakespeare and more, the FICTIONAL STIMULUS is an introduction to the future of reading in the 21st Century and beyond.

Produced by if:book, featuring newly commissioned work from our groundbreaking project MOTFOTHOTBOOK (Museum of the Future of the History of the Book) and designed by Toni Le Busque, the FICTIONAL STIMULUS is for bookgroups and individual readers who know what they love about books, and want to see what might be gained from new ways of reading.

The FICTIONAL STIMULUS includes a signed limited edition handmade ‘menu’, a complete downloadable ebook and links to a range of specially commissioned litchbits from writers asked to imagine the future of stories.

The FICTIONAL STIMULUS will give you plenty of fodder for a fantastic bookgroup or discussion with friends, and there’s the chance to WIN A PRIZE by sending in your own stories, poems and opinions on the future of reading.

to sign up either leave an email in the comments section here or on the Bookfutures page

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Trying to think a bit outside the box or at least change my conception of the box

There’s endless talk these days about ebook readers, Kindle and all its e-ink cousins, and future tablets from Apple and other phone makers. There’s nothing wrong with the fact that these devices are all designed to emulate the experience of reading printed material, but this is a starting point not the end point. The forms are going to evolve in ways we can’t imagine and they may not be best served by 2-D paper emulators.

Reading this description of new functionality in Microsoft’s XBox, I started wondering whether as game box evolves into an all-purpose “entertainment hub” which is thoroughly integrated into major social networks, whether it might extend it’s reach to host new forms of (social) reading. if a “book is a place” perhaps one strand of the near future will be to explore that space with a joystick. I hadn’t thought about it before, but perhaps the interview of me in This Spartan Life is a thought experiment in this direction. It would be interesting to re-imagine The Golden Notebook project which proved the viability of an asynchronous reading group as taking place inside of a virtual space where sometimes you would really be “with” other readers and sometimes on your own.

The article that kicked off this little reverie is from this morning’s MIT Technology Review is about a new camera/controller for Microsoft’s X-Box. The sentences that caught my attention:

Microsoft also debuted 10 exclusive new games and the ability to access social networking sites Facebook and Twitter as well as streaming music service Last.fm on the Xbox Live service. The popular social networking sites Facebook and Twitter will be fully integrated into Xbox Live beginning this fall.

There were several announcements about the Xbox 360’s video capabilities including increased functionality with the online Netflix service, 1080p high-definition video downloads, live TV in the United Kingdom and the ability to watch movies online with friends.

Noah Wardrup-Fruin sums up his experience with open peer review

Noah Wardrup-Fruin has a book coming out from MIT Press this summer — Expressive Processing. Together with Doug Sery, his editor at MIT and Ben Vershbow a former colleague at the Institute, Noah used CommentPress to conduct an open peer review of his manuscript. He sums up the experience in an extensive post on his blog, Grand Text Auto.

The Presence of Print

About two years ago, Dan Visel ended a thoughtful post on the New York Public Library’s newly-installed Espresso Book Machine by proposing: “There’s a discussion here that needs to happen.”

In light of the second version of the Espresso Book Machine (EBM) coming out here in England, I’d like to take up his proposal.

First, a little bit about the machine and how it’s improved over the last two years. The machine, produced by OnDemandBooks, put simply, is a device that allows individuals to print books from a digital catalogue on demand. The original idea was to facilitate customers’ access to books on backlist, or, in its more ambitious conceptualization, to function as a vending machine that provided books in places lacking the space in which to store them (think cruise ships). As Dan Visel noted in his original post, the version installed in the NYPL was a hulking contraption that took a long time to produce books outstanding only for their poor quality:

“Holding my copy of Faulkner in my hands, the overwhelming feeling was one of cheapness: the book had been reduced, finally, to being a disposable consumer object, available as easily as a latte at Starbuck’s. The books that the Espresso was putting out every twenty minutes existed for demonstration purposes…I sensed that the books probably wouldn’t be read.”

Since then, ODB have made the size of the machine itself more compact (it still looks like a photocopying machine), decreased the printing time, and significantly widened the material available. As Blackwell’s CEO put it upon the EBM’s installation in its Charing Cross store two weeks ago, “It’s giving the chance for smaller locations, independent booksellers, to have the opportunity to truly compete with big stock-holding shops and Amazon.” Put bluntly, the unique selling point of the EBM from the perspective of book store owners is that the breadth of titles immediately available will lure customers away from sites like Amazon and back into their bricks-and-mortar shops.

Also since then, a lot has happened in the publishing industry. Not the least of which is Kindle 2, as well as the iPhone, Apple’s imminent Kindle-Killer, and the expansion of GoogleBooks’ content (which includes magazines as well as books). Instantaneous access to limited, but rapidly-expanding, content is now expected and easy in numerous digital formats.

So, what has the EBM got that the digital formats haven’t? One thing, really. Presence. While the cost of books printed by the EBM is low, swathes of online content is free, and e-readers will, like all technology, decrease in price in due time. On-screen readability has progressed impressively and may even have an advantage over the smaller fonts used in standard printed books. If the iPod is any indication, people are willing to pay a more significant amount up front in exchange for total and ubiquitous access to their personal catalogue–up until now, of music, but perhaps soon of books as well. Many music stores now allow customers to download music from in-store digital stations in order to avoid purchasing the physical CD itself. The EBM, with a comparable catalogue, suggests that the same will soon be available to people toting along their E-Books to the store. Plug in, download, read. All these factors would seem to spell a speedy end to the EBM.

So again, I ask, what has the EBM got that the digital formats haven’t? And again the answer is Presence. If people are going to continue to purchase paper books, publishers have got to do for books what the music industry failed to do for CDs. While the CD-stand or -case was almost de rigeur in 1990s interior decor, people soon realized that a tower of transparent plastic was not the personality statement piece they imagined it could be. Yet vinyl records, despite their obsolescence, retain their appeal for many, from nostalgic Baby Boomers to cool-hunting teens. Perhaps it is, after all, the sound quality, but I’m willing to bet that the labor put into sleeves and liner notes is what has guaranteed their enduring appeal. Records are fetishized objects, while CDs are shiny detritus disks. At this moment in time, books seem poised to go either way.

How can the EBM and the publishing industry at large promote the permanence of the paper book? Capitalize on what already makes the book appealing. Its Presence. Looking at my own bookshelves at the moment, my eye is pleased to see three elegantly-designed paperbacks of Murakami’s works leaning against one another, while lamenting that the fourth was produced by a publisher with a lesser eye for design and display. My Penguin Classics form a band of black crowned with a single red striation, and my cookbooks’ spines flash an array of color that, frankly, makes me hungry.

Of course, all of these are mine. I chose them, I own them, I feel their presence in my home. But many, many other people also own them. They have what I have like the certain green-and-white paper coffee cups alluded to in the Espresso Book Machine’s name. But what if, instead of being a customer, accustomed to the books that weren’t customized to me, I were a patron? What if books, instead of being made more disposable, were restored their status of belonging? What if printing allowed us to imprint ourselves on the books that we’ve printed? All of this seems to oppose what printing inherently is and what it revolutionized, as Elizabeth Eisenstein argued. But it is easy to argue that standardization was not an inevitable end to a technologically-determined progression.

What if the EBM allowed us to design books the way we want to see them and want them to be seen? At present, the only choice allowed is paper color. And the desire to keep prices low–an appeal that Amazon and online content already have–demands that options be limited. But what if I could change the cover of that fourth Murakami book to a design more fitting with the other three? What if publishers commissioned more than one artist to produce cover designs that competed for our attention and won them pretty royalties? What if I could hide my Harlequin romance novel behind a cover bearing Kafka’s name? What if I could expand the margins of pages in order to accommodate my written conversations with the text? What if I could append an index with a concordance of a single character’s use of the word “phoney”? What if I could print up the journalistically-toned novels of Marquez in Courier font and the Iliad in Herculanum? What if I thought something as precious as Poe deserved octavo? What if I printed the Wife of Bath’s Tale before the Knight’s?

The what-ifs are many and obviously expensive. But what if we could bend and shift the standardization that is the essence of printing? What if we could change printing to be more present that it already is? Physical witness to a choice made now and in the present.

Gamers Anonymous

I am not a gamer.

I do not consider myself a gaming enthusiast, I do not belong to any kind of “gaming community” and I have not kept my finger on the proverbial pulse of interactive entertainment since my monthly NES newsletter subscription ran out circa 1988.

Save a few momentary aberrations–a brief fling with “Doom” (’93), a torrid encounter with “Half-Life” (’98), a secret tryst with “Grand Theft Auto III” (’01)–I’ve worked to keep my relationship to that world at arm’s length.

Video games, I’d come to believe, had not significantly improved in twenty years. As kids, we’d expected them to evolve with us, to grow and adapt to culture, to become complex and sophisticated like the fine arts; rather, they seemed to remain in a perpetual state of adolescence, merely buffing-out and strutting their ever-flashier chops instead of taking on new challenges and exploring untapped possibilities. Maps grew larger, graphics sharpened to near-photorealistic quality, player options expanded, levels enumerated, and yet the pastime as a whole never advanced beyond a mere guilty pleasure.

Every time a friend would tug my sleeve and giddily drag me to view the latest system, the latest hyped-up game, I’d find myself consistently underwhelmed. Once the narcotic spell of a new virtual landscape wore off, all that was left was the same ossified product game producers had been peddling since 1986. Characters in battle-themed games still followed the tired James Cameron paradigm–tough guy, funny guy, butch girl, robot; stories in “sandbox” games were as aimless and hopelessly convoluted as ever.

This is to say nothing of the interminable interludes that kept appearing between levels, clearly designed by wannabe action movie directors. Fully scripted scenes populated by broad stereotypes would go on for five or even ten minutes at a time, with the “camera” incessantly roving about, punching in, racking focus, jump-cutting., as though an executive had instructed his team to “make it edgier, snappier, more Casino.”

Where was the modern equivalent to the Infocom games, those richly imagined text-based worlds that put to shame any dime-a-dozen title from the Choose Your Own Adventure series? This isn’t nostalgia talking. Infocom, like its predecessors in BASIC, put out games written by actual authors; not only did they know how to construct engaging stories and fleshed-out characters, they foresaw the opportunities presented by non-linear narratives and capitalized on their interactive potential.

Was it me, or had “refinement” in the subsequent years become a dwindling pipe-dream, like accountability in broadcast journalism?

Recently, however, I had a change of heart. On a trip upstate to visit a friend, I was somewhat reluctantly introduced to the latest installment of the “Fallout” series, third in the sprawling, post-apocalyptic trilogy, only to emerge three days later, transfigured.

Here’s the gist: your character has been born into an alternate reality, one in which nuclear war has ravaged the planet at some point immediately following World War II. Subsequent generations have grown up inside elaborate subterranean fallout shelters where culture, if not technology, has remained frozen in the 50s–faded pastel colors and lollipop iconography share space with rusting robots and exotic weaponry, almost as a form of collective denial. Those that have ventured out into the radioactive wasteland have cobbled together ersatz settlements from the ruins, a la Mad Max, in which they are able to form intimate, scavenger communities subsisting on scraps. You enter the game as an infant, grow up in an underground vault, and eventually embark on a journey that takes you deep into the perilous outdoors.

So far, a familiar, setup. But a few things set the game apart from the standard fare. For one thing, the relationship between the player and the character is mediated by something called the “pip-boy”–a digital interface strapped to the character’s arm which holds all the information relevant to your status: health points, radiation levels, weapons & ammo, etc., plus a working map of places you’ve explored and the details of your current quest.

As far as I know, this is the first time a game has come up with anything like this. The pip-boy acts as a bridge between the ‘diegetic’ and ‘non-diegetic’ worlds, a thing rooted in and motivated by the artificial construct of the game, yet positioned w/r/t the player such that he has a lifeline to the virtual realm at all times. This simple step–providing an internally-justified means of communication between player and character–makes a crucial psychological difference. It’s a bit like having a “Dungeon Master” along with you, only this time it’s not an extremely annoying child.

The overall effect on one’s consciousness is unnerving. That strange, not-quite-real sense of space that follows a day spent in a museum, or even an amusement park, permeates the outside world for long stretches of time.

Broadly speaking, this is something we ask of all art: to tweak and enrich our subjective experience of reality. (Good stuff does this for a day; great stuff does it for a lifetime.) But we also ask it introduce us to concepts, to construct microcosms that allow ideas to take shape and find a sort of aesthetic cohesion–and this is where video games, indeed all games, have historically fallen short.

“Fallout 3” is a totally different animal. It’s a game, yes, but only insofar as it adheres to a set of specific gameplay rules; beyond that, it’s a nest of integrated narratives more in keeping with Julio Cortazar ‘s novel, Hopscotch, than, say, a game of hopscotch.

Indeed, the playing of the game is merely the entry point, a framing device that allows you access to a furiously detailed world. Is this in-itself new? To some degree, the same could be said about last year’s “Grand Theft Auto”–the player enters the alternate New York as Nico Belic, a Slavic thug just in from Eastern Europe, and the story unfolds more or less according to the manner of one’s choosing. Missions are accepted or denied, bad guys are mowed-down or spared, items are acquired or neglected.

The difference is that the game “doesn’t care.” Like “The Sims,” “Grand Theft Auto” does not offer meaningful consequences to irrevocable actions. Getting a prospective girlfriend to invite you upstairs after a date simply results in an opportunity for another date; outrunning a cop means only that you will no longer be chased by him.

Conversely, a particular course of action in “Fallout 3” actually affects the way in which the story is told. Defusing a bomb in the center of town doesn’t just award you with karma points, it opens doors in the story while closing others. Enslaving a citizen doesn’t just turn a once-friendly community against you, it puts you in good standing with the slavers you encounter later on, which in turn enables a set of otherwise unavailable choices. The game “cares” what you do, though it does not “judge” you–again, like a Dungeon Master.

In Aristotelian terms, the dramatic action ultimately takes precedent over the “obstacles.” No matter which choices you make, or in what order you make them, the game is predicated on an ingeniously organized narrative architecture that presents a nested series of dramatic events and corresponding consequences, the constellation of which determines the “plot points” of your particular quest. Like life, what you do is who you are.

Which is not to suggest that we begin judging games by the standards of drama proper. Equating the two raises the same red flags we find ourselves facing when we start calling jazz “America’s classical music” and comic books “graphic literature.” Neither idiom seems to benefit from the association. On the contrary, it suggests that we continue evaluating them on their own terms, for what they can accomplish given their own advantages and constraints–only with the bar set much, much higher.

It also means that those of us too snooty to accept certain terms for ourselves might have to buck up and swallow our pride.

Hell, I’m a gamer.

—

Alex Rose is a co-founding editor of Hotel St. George Press and the author of The Musical Illusionist and Other Tales. His work has appeared, most recently, in The New York Times, Ploughshares and Fantasy Magazine. His story, “Ostracon,” will be included in the 2009 edition of Best American Short Stories.

notes from around the web

- On April 26 in Los Angeles, haudenschildGarage presents a performance entitled The Last Book, an “attempt to resurrect the medieval illuminated manuscript through the invocation of our current alchemy, the new technologies, to conjure a future as the past in reverse”. The artists and writers involved include Steve Fagin, Mary Gaitskill, Mian Mian, Leslie Thornton, Davina Semo, and Greg Landau; their site has more information.

- Max Bruinsma has an interesting essay at Limited Language entitled “Typographic Design for New Reading Spaces”, addressing the issue of designing for screen reading and why text on screens is still generally so ugly.

- Mediabistro points out Moulinarn Mobile Books (website under construction), devoted to publishing content specifically for the iPhone platform. Their content doesn’t seem especially interesting, but it does look like it’s not a generic e-book reader.

- Those with a subscription to the Chronicle of Higher Education might be interested in this article about Matthew Kirschenbaum work on writers’ digital archives.

- DiRT is the Digital Research Tools wiki, a collection of useful resources for scholars doing research digitally. Most of the tools they point out are open-source; it’s nice to have all these things in one place. More advanced users might look at XTF, an interesting new public domain extensible text framework designed to make archives digitally accessible.

- The Digital Poetics blog suggests a new method of film criticism: grabbing a screen shot at 10 minutes, 40 minutes, and 70 minutes into the movie & talking about what’s on the screen at that instant and how it relates to the rest of the movie.

- Dene Grigar’s “Electronic Literature: Where Is It?” has been up at the Electronic Book Review for a while, but it’s still worth a look. I’m not entirely sure it will convince skeptics, but it is a good overview of the present of electronic literature and its place in the academy.

- Brazilian novelist Claudio Soares has put his 2006 novel Santos Dumont Número 8: O Livro das Superstições into the Institute’s CommentPress. He’s given all of the characters Twitter accounts; an impressive online presentation introduces the online version of the novel, which looks to be a fairly serious undertaking although put together with free tools. Once again, I wish I spoke Portuguese. (Edit: Claudio Soares suggests three auto-translated links – http://ow.ly/2g0r, http://ow.ly/2g0x, http://ow.ly/2g17 – for English speakers who wish to get a better idea of the project.)

- And finally, if:book London presents Songs of Imagination and Digitisation, a variety of new media responses to the work of William Blake.

oulipo in new york

The most prominent members of the Oulipo are making a rare descent upon New York this week; there are readings at the New School tonight and in Pierogi in Williamsburg on April 3rd. (A complete schedule of events can be found here.) Oulipo is the Ouvroir de littérature potentielle (the workshop of potential literature), a group of mostly French mathematicians and writers who use constraint to generate new literary forms. The most well-known Oulipians are the late Marcel Duchamp, Raymond Queneau, Italo Calvino, and Georges Perec; the group, however, carries on, and Marcel Bénabou, Anne Garréta, Hervé Le Tellier, Ian Monk, Jacques Roubaud, and Harry Mathews will be talking about their work.

Part of the occasion for their arrival is the publication of Jacques Roubaud’s The Loop in Jeff Fort’s English translation by the Dalkey Archive. (There’s a launch party tomorrow night at Idlewild Books.) The Loop, originally published in France in 1993, is the second volume of a series of works collectively called The Great Fire of London; five volumes have been published in France, and a sixth and final volume is in the works. While the first volume (published under the same name as the series) was translated into English in 1992, it’s taking a while for the rest of them to appear here. The Great Fire of London is worthy of mention here because it’s perhaps the most extended literary use of hypertext. The two volumes published here have “Fiction” stamped on the back cover, but that’s not entirely accurate: these books are writing about writing, a metafictional memoir if you will, arranged around Roubaud’s inability to write a novel entitled The Great Fire of London. (Marcel Bénabou confronts this issue more concisely in a book of his own entitled Why I Have Not Written Any of My Books.)

“Metafiction” is a word used in criticism to damn writing more often than not; especially in this country, it’s frequently presented as ivory tower excess, obfuscatory, the enemy of American plain-speaking. The Great Fire of London is certainly subject to these criticisms: Roubaud is dazzlingly intelligent (while a professor of mathematics at the Sorbonne he studied for a second doctorate in poetry), and his writing pulls no punches; within the first chapter of The Loop, the reader is faced with explorations of the ideas of Nicholas of Cusa, Wittgenstein, and Kripke, to name only the philosophers. But The Great Fire of London is also a very personal work: as explained in the first volume, Roubaud began writing the work after the death of his wife Alix as a means of working through grief. His wife’s presence hovers over the first two volumes of the work, albeit obliquely: her death is never discussed directly. Roubaud wakes every morning before dawn and writes a section of his evolving book; he forces himself to work linearly, not to revise, not to leave anything out. The first volume focuses on his conception of his project and his writing, though there are memoiristic departures: Roubaud’s ideas about how croissants should work and how jam was prepared in his childhood in Provence; the memory of an American love affair and his tastes in English novelists all make their way in to his narrative.

Roubaud does not constrain himself to a strictly linear writing style: periodically there are interpolations, glosses on passages of his linear book that go on for a few pages; interpolations frequently have their own interpolations. There are also bifurcations: sometimes Roubaud sees another way that his narrative could go and follows it for a longer period. The reader flips back and forth through the sections of the book; to follow Roubaud’s suggested pathway (which, he points out, is not the only way to read the book) requires three bookmarks.

Here, as a demonstration, is a diagram of the first chapter of The Loop, showing how 90 pages of the book’s text are interconnected: the chapter itself is about 30 pages, there are about 30 pages of interpolations, and the bifurcation also lasts for 30 pages. Horizontal connections are interpolations, where linear text is interrupted to suggest a possible digression; vertical connections are linear connections. The complete book is about six times this length; I’d love to see a complete map of the book, though I haven’t found one yet.

It should be noted that this diagram only captures the explicit interconnections in the book; there are also implicit interconnections, and especially in the bifurcation Roubaud refers back to other interpolations that the reader trying to follow the explicit map will not yet have read. Like Cortázar’s Hopscotch, this is a book that demands re-reading. Dominic Di Bernardi’s afterword to the English translation of The Great Fire of London, “The Great Fire of London and the Destruction of the Book”, argues that Roubaud’s work is the future of the book: the future was hypertext. Read 17 years later, this feels like a flying car vision of the future; the hypertext future that everyone imagined in 1992 never really arrived.

Roubaud’s work, by contrast, now feels like a deeply personal project: one man’s attempt to map out his memory as accurately as possible using the formal tools available to him, trying to smash the architecture of memory into the Procrustean bed imposed by the strict linearity of our readership of text. In The Great Fire of London, Roubaud explains how he works with a typewriter, an electronic model named Miss Bosanquet III (named after the secretary of Henry James); Miss Bosanquet III’s primitive word-processing capabilities allowed him to edit one line of text before it was printed. With The Loop, Roubaud started composing using a Mac. The results are obvious as soon as one opens the book: text is bolded, italicized, and underlined, and the type size changes. The Loop is primarily about Roubaud’s childhood, but it’s also necessarily an exploration of how writing can approach the problem of mapping memory, and, by extension, how technology changes writing. The problem for the reader of Roubaud is that technology changes reading as well: we’re left trying to catch up.

design and dasein: heidegger against the birkerts argument

Here and elsewhere in the blogosphere, much ink has been spilled — or rather, many pixels generated — regarding Sven Birkerts’s “Resisting the Kindle,” which contends that the e-reader’s rise augurs ill for our ability to contextualize information. The argument hinges on a conditional premise, the soundness of which I doubt: “If … we move wholesale into a world where information and texts are called onto the screen by the touch of a button … [then] we will not simply have replaced one delivery system with another.” At his most dystopian, Birkerts foresees “an info-culture … composed entirely of free-floating items of information and expression, all awaiting their access call.”

Birkerts’s skepticism seems more an indictment of human nature than of the Kindle itself, and I think his assumptions about our capacity to “replace” are misguided. In defending or repudiating his stance, bloggers have invoked everyone from McLuhan to Pascal to Derrida. Bearing this continental mélange in mind, I’d like to call to the stand Herr Martin Heidegger, existentialist and phenomenologist par excellence.

Don’t worry — I’ll try to keep this painless.

In his seminal Being and Time, Heidegger considers equipment and utility: how we relate to our tools, how the tools relate to one another, and how a network of tools mitigates our surroundings. “Equipment,” he avers, “can genuinely show itself only in dealings cut to its own measure” (98).* Well-designed tools possess something he dubs “readiness-to-hand.” Roughly defined, the more something is suited to the use it is made for, the more ready-to-hand it becomes. Readiness-to-hand entails a kind of integration with the environment, an invisibility; the tool belongs so much in the world that we seldom realize we’re using it as we work. So that we may gape at his obscurity, here’s how Heidegger puts it:

The peculiarity of what is proximally ready-to-hand is that, in its readiness-to-hand, it must, as it were, withdraw in order to be ready-to-hand quite authentically. That with which our everyday dealings proximally dwell is not the tools themselves. On the contrary, that with which we concern ourselves primarily is the work — that which is to be produced at the time; and this is accordingly ready-to-hand too. The work bears with it that referential totality within which the equipment is encountered. (99)

Consider, for example, a computer keyboard. When I type on mine, I’m ordinarily unaware of it. Since it’s well-designed and fully functioning, I have no phenomenological reason to take notice of its existence — instead, I concentrate on what I’m typing. The keyboard is incorporated in my location, existing in tandem with my monitor, my lamp and, yes, the intimidating paperback edition of Being and Time resting on my desk.

Of course, if the keyboard broke, or if it were inherently flawed, this wouldn’t be the case, and it’s for this reason that Heidegger introduces “obtrusiveness,” one way of distinguishing between well-wrought equipment and defective tools. The latter make us increasingly aware of their presence and less at ease in our environs; they simply don’t seem to fit into the world as we’ve constructed it. This is the last time I’ll quote our man:

When we notice what is un-ready-to-hand, that which is ready-to-hand enters the mode of obtrusiveness. The more urgently we need what is missing, and the more authentically it is encountered in its un-readiness-to-hand, all the more obtrusive does that which is ready-to-hand become — so much so, indeed, that it seems to lose its character of readiness-to-hand. It reveals itself as something just present-at-hand and no more, which cannot be budged without the thing that is missing. The helpless way in which we stand before it is a deficient mode of concern, and as such it uncovers the Being-just-present-at-hand-and-no-more of something ready-to-hand. (103)

Onto Birkerts, then. The Kindle may feel, at present, isolated and bereft of context, but this is because its readiness-to-hand is concealed by a lack. Something is missing, or, to use Heidegger’s jargon, “obtruding.” Birkerts maintains that the issue is one of context, but this is perhaps irrelevant. What matters is not the nature of what’s missing but that something is missing at all. In Heidegger’s philosophy, people will resist imperfect equipment, especially when its faults obtrude upon their interactions with the world.

If designers solve the Kindle’s problems — whatever they may be — satisfactorily, e-readers could supplant traditional, printed books. We might, that is, come to use the Kindle for identical tasks, in otherwise identical environments, and so enable a radical shift in information access without surrendering anything. But if designers can’t remedy this sense of Heideggerian obtrusiveness, then the risk of wholesale displacement is practically nil. Unless its successor is fully accommodating, the “delivery system” will not be replaced. What obtains for e-readers instead will be tenuous coexistence at best and outright failure at worst.

Thus, the most tendentious part of Birkerts’s argument has little to do with the Kindle or context. It’s that he believes humanity would wittingly adopt deficient tools at the expense of effective ones. This fundamental cynicism is, to a point, understandable; much of marketing and advertising, after all, devotes itself to convincing us that what’s new is necessarily superior, and in the marketplace we’re suckers for such baseless claims. (At this point, any sticker that reads “New and Improved!” seems almost redundant.) But Birkerts underestimates, I think, the functional and aesthetic requisites of an average reader. If Heidegger is right, then the catastrophic, decontextualized info-culture of Birkerts’s imagination is patently absurd — readers won’t, in the short- or long-term, shutter our libraries just because some novel, convenient alternative has asserted itself.

“We misjudge it,” writes Birkerts of the Kindle, “if we construe it as just another useful new tool.” But this is exclusively what it is, at the moment. In order to advance as equipment, the Kindle must demonstrate the readiness-to-hand of that which it endeavors to replace. It hasn’t. Until it does, any talk of supersession strikes me as alarmist.

—

*These citations come from the John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson translation. Heidegger’s style, especially in English, is notoriously labyrinthine and often straight-up unreadable. If, someday, someone can endure the entirety of Being and Time on a Kindle, I think we can safely say the e-readers have won.

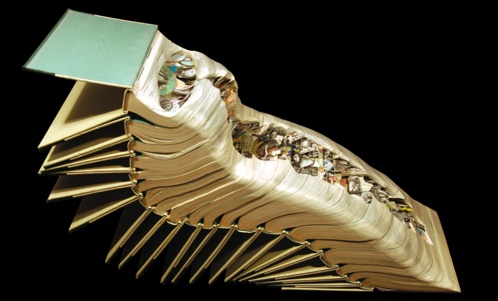

extraordinary book sculpture

Brian Dettmer creates these extraordinary sculptures by amalgamating, modifying and mutating books.

Looking at these images of the physical matter of books, remixed into sculptures, I’m reminded of the process that texts are increasingly going through once digitized: amalgamated, remixed, reformed into new entities.

Dettmer’s sculptures invite us to think about deeply-held taboos around the sanctity of books as objects; a conversation that recurs – especially in the context of e-readers – around discussion of digitized text.

Recycling, reimagining, repurposing the cultural glut amidst which we currently exist feels in many ways an appropriate artistic mode for today. Is authorship really so sacred that remixed works cannot themselves be things of beauty and value? Or, like European villages dismantling local medieval chateaux to build outhouses, are we taking our cultural history so completely for granted that we’re in danger of forgetting or destroying millennia of culture in a thoughtless reappropriation of its materials for our current preoccupations?

Dettmer’s show opens April 3 at the Packer Schopf Gallery in Chicago.

(Via Boing Boing)

will the real iPod for reading stand up now please?

OK, so first of all: this isn’t an article about whether or not ebooks are a good thing. But I was thinking this morning about the now hackneyed idea that we’re moments away from an ‘iPod moment for ebooks’, and trying once again to work out why I think this is so very wrong. I’ve concluded that it’s because of the physical qualities of books. But not in the way you’d think.

No discussion of the future of the book is complete without someone saying, as if they’d thought of it first, ‘But books are tactile and sensory as well as intellectual, what about the feel and smell?’. Yeah, I like to read in the bath, I like to scribble in the margins, etc. This discussion has been extensively rehearsed, by people much smarter than me, so let’s sidestep this issue for a moment. But the physicality of books impacts on their contents, too, and it is this that makes the iPod a misleading comparison for the kind of content that might work on an e-reader.

Let’s look at books for a moment. While in the early Wild West publishing days of the 18th-century print boom works were produced in a bewildering array of formats (elephant folio, pamphlet, poster, flyer, handout along with more familiar books) in today’s mature publishing industry there is an inverse correlation between the size of the print run and the variation in the book’s dimensions. In other words, the more mass-market a book, the more likely it will be to conform to the average book dimensions: 110-135mm wide, by 178-216mm high. This is the easiest size to produce inexpensively, and sell at a price point the market will bear.

Length is determined as well, by manufacturing constraints at the top end, and the fixed overheads of printing at the bottom. Bookshops are crammed with full-length books whose contents could just as well be communicated in a short essay, or even in the title alone: I’m thinking of Feel The Fear And Do It Anyway, but a glance at the self-help or business shelves of your local bookshop will show you plenty more. And yet to make economic sense they have to be padded out for publication in ‘proper’ book size. But to conclude from this (as many unwittingly do) that long-form books are necessarily the best, rather than just the most familiar, way of communicating ideas is mistaken; and to assume that this practice will transplant to e-readers, imagined as a kind of iPod for these long-form essays, is just wrong.

Look at the Web. The attention economy at its most feral. Whatever you’re writing, there is always better, more engaging, more pornographic or immediately relevant content only a click away. If I make this article too long you won’t finish it. In terms of print tradition, long-form writing is best; but online, brevity really is the soul of wit. Or, rather, the soul of not being ignored. Does this mean that – on the assumption that long-form is intrinsically good – the Web is ruining our ability to think deeply? Birkerts’ recent Atlantic article ‘Resisting the Kindle’ (see Bob’s post below) rehearses, after a fashion, some of these concerns; but a counter-perspective might argue simply that, without the physical constraints of print publishing, we are experimenting with new ways to communicate.

I read books, read blogs, I twitter compulsively. I use these different formats for different kinds of experience. I see no contradiction: what I’m getting at here is that the e-reader is being treated as though it is a viable vehicle for long-form writing, in a way that ignores the essential fact that long-form writing and reading is rooted in paper, and book manufacturing.

So, back to the ‘iPod for reading’ metaphor. Its proponents generally don’t dig deeper than ‘here is a small square device for storing and consuming lots of music’. The implication is that we can hop blithely from that to ‘here is a small square device for storing and consuming lots of text’. Regardless of stirring promises of e-books containing audio, video, fancy schmancy links and so on, the common understanding – and, indeed, the hope of the publishing industry – remains that this is a digital device for reading long-form texts. But this ignores the effect that iPods – or, more generally, mp3s – are having on how music is distributed. Once sold as albums, whether on LPs or CDs, music is increasingly sold by the micro-unit – a single song. A unit of content typically around 3 or 4 minutes long rather than 60-75 minutes.

It makes economic sense to sell LPs or CDs at a runtime of 60-odd minutes. It makes economic sense to sell books of around 80,000 words. But music for iPods can be sold song by song. So, extrapolating from this to an iPod for reading, what is the written equivalent of a single song? In a word (or 300), belles lettres.

And the Web is full of belles lettres. Now and then in my wanderings around the Web, I come across something and think ‘That’s a really important essay’. And I worry about the ability of the Web to take care of it for me: link rot always sets in eventually, Wayback Machine or no. I can’t print it all out. So how do I keep such articles? I would welcome a device designed for downloading and archiving essays I think are important, a virtual library device for the belles lettres of today.

Armed with such a device, creating playlists, mashups, collages of our favourite short works, we might become a generation of digital Montaignes, annotating and expanding our collective discourse. Blogging is already, in effect, the re-emergence of belles lettres; and while blog posts are typically written for the moment, a device that could earn the blogger a small sum (and the cachet of being considered worthy of archiving) for every essay downloaded might well inspire a renaissance in short work written for a longer lifespan.

As a device for consuming a kind of writing – long-form – developed within the constraints of physical print, e-readers are a niche product. Reading a long-form book on an e-reader is a bit like teleconferencing: it’s OK as far as it goes, but the meeting format evolved from haptic, as much as informational, constraints and still works better that way. There may be people out there who listen to entire albums, from start to finish, one at a time, on their iPods; I’m willing to bet there will a few who will enjoy slogging through long-form writings, one at a time, on a digital device. I don’t see it going mainstream. But a device for collating and archiving good, important, digital short writing? I want one.

So, please, can we forget about the handful of eccentrics who want to ruin their eyes wading through War and Peace on a tiny LCD screen. Instead, let’s bring on the real iPod for reading: something that lets me download, archive, tag annotate, share, playlist and categorise short-form works that would otherwise disappear into the link-rot mulch of yesterday’s Web. Let’s figure out a business model, an iTunes for micro-articles. Let’s take short-form digital writing seriously.

(Cross-posted from sebastianmary.com)