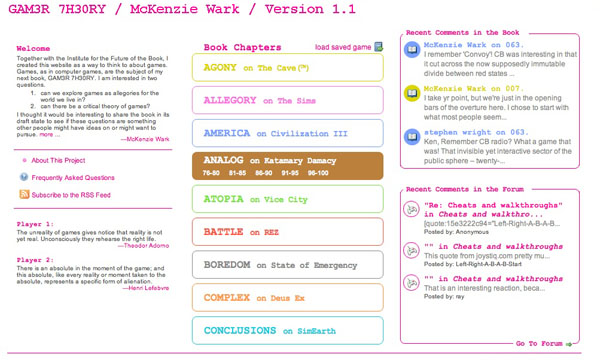

The Institute has published its first networked book, GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1 by McKenzie Wark! This is a fascinating look at video games as allegories of the world we live in, and (we think) a compelling approach to publishing in the network environment. As with Mitch Stephens’ ongoing experiment at Without Gods, we’re interested here in a process-oriented approach to writing, opening the book up to discussion and debate while it’s still being written.

Inside the book, you’ll find comment streams adjacent to each individual paragraph, inviting readers to respond to the text on a fine-grained level. Doing the comments this way (next to, not below, the parent posts) came out of a desire to break out of the usual top-down hierarchy of blog-based discussion — something we’ve talked about periodically here. There’s also a free-fire forum where people can start their own threads about the games dealt with in the book or about the experience of game play in general. It’s also a place to tackle meta-questions about networked books and to evaluate the successes and failings of our experiment. The gateway to the forum is a graphical topic pool in which conversations float along axes of time and quantity, giving a sense of the shape of the discussion.

Both sections of GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1 — the book and the forum — are designed to challenge current design conventions and to generate thoughtful exchange on the meaning of games. McKenzie will actively participate in these discussions and draw upon them in subsequent drafts of his book. The current version is published under a Creative Commons license.

And like the book, the site is a work in progress. We fully intend to make modifications and add new features as we go. Here’s to putting theory into practice!

(You can read archived posts documenting the various design stages of GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1 here.)

Category Archives: the_networked_book

good discussion(s) of kevin kelly article

In the New York Times own book discussion forum, one rirutsky opines eloquently on the problems with Kelly’s punch-drunk corporate optimism:

…what I find particularly problematic is the way that Kelly’s “analysis”–as well as most of the discussion of it–omits any serious mention of what is actually at stake in the utopian scheme of a universal library (which Borges, by the way, does not promote, but debunks). It has little to do with enabling creativity, but rather, with enabling greater corporate profits. Kelly is actually most close to the mark when [he] characterizes the conflict over digital books as a conflict between two business models. Of course, one gets the impression from some of Kelly’s writings that for him business and creativity are more or less the same thing….

….A more serious consideration of these issues would move away from the “old” binary antagonisms that Kelly outlines (surely, these are a relic of a pre-digital age) and think seriously about how society at large is changed by digital technologies and techniques. Who has the right to copy or to make use of data and who does not? In a world of such vast informational clutter, doesn’t power accrue to those who can afford to advertise? It is worth remembering, too, that searching is not, after all, a value-free operation. Who ultimately will control the searching and indexing of digital information? Should the government–or private corporations–be allowed to data mine the searches that people make? In short, who benefits and who loses from these technological changes? Where, precisely, is power consolidated?

Kelly does not even begin to deal with these sorts of serious social issues.

And from a typically immense Slashdot thread (from highlights conveniently collected by Branko Collin at Teleread) — this comes back to the “book is reading you” question:

Will all these books and articles require we login to view them first? I think having every book, article, movie, song, etc available for use anytime is a great idea and important for society but I don’t want to have to login and leave a paper trail of everything I’m looking at.

And we have our own little thread going here.

on ebay: collaborative fiction, one page at a time

Phil McArthur is not a writer. But while recovering from a recent fight with cancer, he began to dream about producing a novel. Sci-fi or horror most likely — the kind of stuff he enjoys to read. But what if he could write it socially? That is, with other people? What if he could send the book spinning like a top and just watch it go?

Say he pens the first page of what will eventually become a 250-page thriller and then passes the baton to a stranger. That person goes on to write the second page, then passes it on again to a third author. And a fourth. A fifth. And so on. One page per day, all the way to 250. By that point it’s 2007 and they can publish the whole thing on Lulu.

The fruit of these musings is (or will be… or is steadily becoming) “Novel Twists”, a ongoing collaborative fiction experiment where you, I or anyone can contribute a page. The only stipulations are that entries are between 250 and 450 words, are kept reasonably clean, and that you refrain from killing the protagonist, Andy Amaratha — at least at this early stage, when only 17 pages have been completed. Writers also get a little 100-word notepad beneath their page to provide a biographical sketch and author’s notes. Once they’ve published their slice, the subsequent page is auctioned on Ebay. Before too long, a final bid is accepted and the next appointed author has 24 hours to complete his or her page.

Networked vanity publishing, you might say. And it is. But McArthur clearly isn’t in it for the money: bids are made by the penny, and all proceeds go to a cancer charity. The Ebay part is intended more to boost the project’s visibility (an article in yesterday’s Guardian also helps), and “to allow everyone a fair chance at the next page.” The main point is to have fun, and to test the hunch that relay-race writing might yield good fiction. In the end, McArthur seems not to care whether it does or not, he just wants to see if the thing actually can get written.

Surrealists explored this territory in the 1920s with the “exquisite corpse,” a game in which images and texts are assembled collaboratively, with knowledge of previous entries deliberately obscured. This made its way into all sorts of games we played when we were young and books that we read (I remember that book of three-panel figures where heads, midriffs and legs could be endlessly recombined to form hilarious, fantastical creatures). The internet lends itself particularly well to this kind of playful medley.

if:book in library journal (and kevin kelly in n.y. times)

The Institute is on the cover of Library Journal this week! A big article called “The Social Life of Books,” which gives a good overview of the intersecting ideas and concerns that we mull over here daily. It all started, actually, with that little series of posts I wrote a few months back, “the book is reading you” (parts 3, 2 and 1), which pondered the darker implications of Google Book Search and commercial online publishing. The article is mostly an interview with me, but it covers ideas and subjects that we’ve been working through as a collective for the past year and a half. Wikipedia, Google, copyright, social software, networked books — most of our hobby horses are in there.

The Institute is on the cover of Library Journal this week! A big article called “The Social Life of Books,” which gives a good overview of the intersecting ideas and concerns that we mull over here daily. It all started, actually, with that little series of posts I wrote a few months back, “the book is reading you” (parts 3, 2 and 1), which pondered the darker implications of Google Book Search and commercial online publishing. The article is mostly an interview with me, but it covers ideas and subjects that we’ve been working through as a collective for the past year and a half. Wikipedia, Google, copyright, social software, networked books — most of our hobby horses are in there.

I also think the article serves as a nice complement (and in some ways counterpoint) to Kevin Kelly’s big article on books and search engines in yesterday’s New York Times Magazine. Kelly does an excellent job outlining the thorny intellectual property issues raised by Google Book Search and the internet in general. In particular, he gives a very lucid explanation of the copyright “orphan” issue, of which most readers of the Times are probably unaware. At least 75% of the books in contention in Google’s scanning effort are works that have been pretty much left for dead by the publishing industry: works (often out of print) whose copyright status is unclear, and for whom the rights holder is unknown, dead or otherwise prohibitively difficult to contact. Once publishers’ and authors’ groups sensed there might finally be a way to monetize these works, they mobilized a legal offensive.

Kelly argues convincingly that not only does Google have the right to make a transformative use of these works (scanning them into a searchable database), but that there is a moral imperative to do so, since these works will otherwise be left forever in the shadows. That the Times published such a progressive statement on copyright (and called it a manifesto no less) is to be applauded. That said, there are other things I felt were wanting in the article. First, at no point does Kelly question whether private companies such as Google ought to become the arbiter of all the world’s information. He seems pretty satisfied with this projected outcome.

And though the article serves as a great introduction to how search engines will revolutionize books, it doesn’t really delve into how books themselves — their form, their authorship, their content — might evolve. Interlinked, unbundled, tagged, woven into social networks — he goes into all that. But Kelly still conceives of something pretty much like a normal book (a linear construction, in relatively fixed form, made of pages) that, like Dylan at Newport in 1965, has gone electric. Our article in Library Journal goes further into the new networked life of books, intimating a profound re-jiggering of the relationship between authors and readers, and pointing to new networked modes of reading and writing in which a book is continually re-worked, re-combined and re-negotiated over time. Admittedly, these ideas have been developed further on if:book since I wrote the article a month and a half ago (when a blogger writes an article for a print magazine, there’s bound to be some temporal dissonance). There’s still a very active thread on the “defining the networked book” post which opens up many of the big questions, and I think serves well as a pre-published sequel to the LJ interview. We’d love to hear people’s thoughts on both the Kelly and the LJ pieces. Seems to make sense to discuss them in the same thread.

a network of books

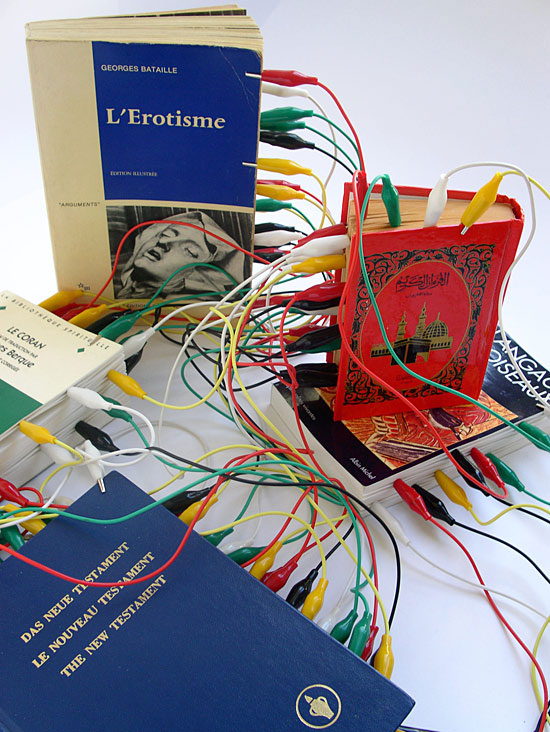

This is the “cover” (it’s an email mag) of the latest issue of artkrush. Part of a 2004 installation by Moroccan artist Mounir Fatmi called “The Connections.”

Connections is the outcome of a reflection which began in the early Nineties, at the time of the war in the Gulf…. At that time, the operations Desert Storm and Desert Fox, preceding the last operation which could be named “Desert, full stop”, established the era of a media oriented war, therefore a war of image, on the very spot of the Revelation, that of the three sacred books, a historic place dedicated to communication. They clearly showed the lack of means of communication and even the lack of communication power of the Arab countries as well as the resurgent fear of technology.

In our calendar, that of Hegira, we are today in 1420, eternally nomads. Our roots are clearly set in the future, as the Arab poet Adonis wrote it. For me, it is an attempt to enter this desert, this collective memory, to remove sand from objects which may lose their identity through the changing of material but will still keep their memory.

A recent comment from Adam Greenfield, author of the just-published “Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing,” seems apropos:

I’ve become all but unable to think of the objects around me except in terms of Actor-Network theory, as sort of depositions or instantiations of a great deal of matter, energy and information moving through the world. And of course, a book is nothing but a snapshot in that regard; you have to do a lot of extra work if you want to prise out and examine the flows it is a part of, or even those it has set up.

defining the networked book: a few thoughts and a list

The networked book, as an idea and as a term, has gained currency of late. A few weeks ago, Farrar Straus and Giroux launched Pulse , an adventurous marketing experiment in which they are syndicating the complete text of a new nonfiction title in blog, RSS and email. Their web developers called it, quite independently it seems, a networked book. Next week (drum roll), the institute will launch McKenzie Wark’s “GAM3R 7H30RY,” an online version of a book in progress designed to generate a critical networked discussion about video games. And, of course, the July release of Sophie is fast approaching, so soon we’ll all be making networked books.

The institue will launch McKenzie Wark’s GAM3R 7H30RY Version 1.1 on Monday, May 15

The discussion following Pulse highlighted some interesting issues and made us think hard about precisely what it is we mean by “networked book.” Last spring, Kim White (who was the first to posit the idea of networked books) wrote a paper for the Computers and Writing Online conference that developed the idea a little further, based on our experience with the Gates Memory Project, where we tried to create a collaborative networked document of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Gates using popular social software tools like Flickr and del.icio.us. Kim later adapted parts of this paper as a first stab at a Wikipedia article. This was a good start.

We thought it might be useful, however, in light of recent discussion and upcoming ventures, to try to focus the definition a little bit more — to create some useful boundaries for thinking this through while holding on to some of the ambiguity. After a quick back-and-forth, we came up with the following capsule definition: “a networked book is an open book designed to be written, edited and read in a networked environment.”

Ok. Hardly Samuel Johnson, I know, but it at least begins to lay down some basic criteria. Open. Designed for the network. Still vague, but moving in a good direction. Yet already I feel like adding to the list of verbs “annotated” — taking notes inside a text is something we take for granted in print but is still quite rare in electronic documents. A networked book should allow for some kind of reader feedback within its structure. I would also add “compiled,” or “assembled,” to account for books composed of various remote parts — either freestanding assets on distant databases, or sections of text and media “transcluded” from other documents. And what about readers having conversations inside the book, or across books? Is that covered by “read in a networked environment”? — the book in a peer-to-peer ecology? Also, I’d want to add that a networked book is not a static object but something that evolves over time. Not an intersection of atoms, but an intersection of intentions. All right, so this is a little complicated.

It’s also possible that defining the networked book as a new species within the genus “book” sows the seeds of its own eventual obsolescence, bound, as we may well be, toward a post-book future. But that strikes me as too deterministic. As Dan rightly observed in his recent post on learning to read Wikipedia, the history of media (or anything for that matter) is rarely a direct line of succession — of this replacing that, and so on. As with the evolution of biological life, things tend to mutate and split into parallel trajectories. The book as the principal mode of discourse and cultural ideal of intellectual achievement may indeed be headed for gradual decline, but we believe the network has the potential to keep it in play far longer than the techno-determinists might think.

But enough with the theory and on to the practice. To further this discussion, I’ve compiled a quick-and-dirty list of projects currently out in the wild that seem to be reasonable candidates for networked bookdom. The list is intentionally small and ridden with gaps, the point being not to create a comprehensive catalogue, but to get a conversation going and collect other examples (submitted by you) of networked books, real or imaginary.

* * * * *

Everyone here at the institute agrees that Wikipedia is a networked book par excellence. A vast, interwoven compendium of popular knowledge, never fixed, always changing, recording within its bounds each and every stage of its growth and all the discussions of its collaborative producers. Linked outward to the web in millions of directions and highly visible on all the popular search indexes, Wikipedia is a city-like book, or a vast network of shanties. If you consider all its various iterations in 229 different languages it resembles more a pan-global tradition, or something approaching a real-life Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. And it is only five years in the making.

But already we begin to run into problems. Though we are all comfortable with the idea of Wikipedia as a networked book, there is significant discord when it comes to Flickr, MySpace, Live Journal, YouTube and practically every other social software, media-sharing community. Why? Is it simply a bias in favor of the textual? Or because Wikipedia – the free encyclopedia — is more closely identified with an existing genre of book? Is it because Wikipedia seems to have an over-arching vision (free, anyone can edit it, neutral point of view etc.) and something approaching a coherent editorial sensibility (albeit an aggregate one), whereas the other sites just mentioned are simply repositories, ultimately shapeless and filled with come what may? This raises yet more questions. Does a networked book require an editor? A vision? A direction? Coherence? And what about the blogosphere? Or the world wide web itself? Tim O’Reilly recently called the www one enormous ebook, with Google and Yahoo as the infinitely mutable tables of contents.

Ok. So already we’ve opened a pretty big can of worms (Wikipedia tends to have that effect). But before delving further (and hopefully we can really get this going in the comments), I’ll briefly list just a few more experiments.

>>> Code v.2 by Larry Lessig

From the site:

“Lawrence Lessig first published Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace in 1999. After five years in print and five years of changes in law, technology, and the context in which they reside, Code needs an update. But rather than do this alone, Professor Lessig is using this wiki to open the editing process to all, to draw upon the creativity and knowledge of the community. This is an online, collaborative book update; a first of its kind.

“Once the project nears completion, Professor Lessig will take the contents of this wiki and ready it for publication.”

Recently discussed here, there is the new book by Yochai Benkler, another intellectual property heavyweight:

>>> The Wealth of Networks

Yale University Press has set up a wiki for readers to write collective summaries and commentaries on the book. PDFs of each chapter are available for free. The verdict? A networked book, but not a well executed one. By keeping the wiki and the text separate, the publisher has placed unnecessary obstacles in the reader’s path and diminished the book’s chances of success as an organic online entity.

>>> Our very own GAM3R 7H30RY

On Monday, the institute will launch its most ambitious networked book experiment to date, putting an entire draft of McKenzie Wark’s new book online in a compelling interface designed to gather reader feedback. The book will be matched by a series of free-fire discussion zones, and readers will have the option of syndicating the book over a period of nine weeks.

>>> The afore-mentioned Pulse by Robert Frenay.

Again, definitely a networked book, but frustratingly so. In print, the book is nearly 600 pages long, yet they’ve chosen to serialize it a couple pages at a time. It will take readers until November to make their way through the book in this fashion — clearly not at all the way Frenay crafted it to be read. Plus, some dubious linking made not by the author but by a hired “linkologist” only serves to underscore the superficiality of the effort. A bold experiment in viral marketing, but judging by the near absence of reader activity on the site, not a very contagious one. The lesson I would draw is that a networked book ought to be networked for its own sake, not to bolster a print commodity (though these ends are not necessarily incompatible).

>>> The Quicksilver Wiki (formerly the Metaweb)

A community site devoted to collectively annotating and supplementing Neal Stephenson’s novel “Quicksilver.” Currently at work on over 1,000 articles. The actual novel does not appear to be available on-site.

>>> Finnegans Wiki

A complete version of James Joyce’s demanding masterpiece, the entire text placed in a wiki for reader annotation.

>>> There’s a host of other literary portals, many dating back to the early days of the web: Decameron Web, the William Blake Archive, the Walt Whitman Archive, the Rossetti Archive, and countless others (fill in this list and tell us what you think).

Lastly, here’s a list of book blogs — not blogs about books in general, but blogs devoted to the writing and/or discussion of a particular book, by that book’s author. These may not be networked books in themselves, but they merit study as a new mode of writing within the network. The interesting thing is that these sites are designed to gather material, generate discussion, and build a community of readers around an eventual book. But in so doing, they gently undermine the conventional notion of the book as a crystallized object and begin to reinvent it as an ongoing process: an evolving artifact at the center of a conversation.

Here are some I’ve come across (please supplement). Interestingly, three of these are by current or former editors of Wired. At this point, they tend to be about techie subjects:

>>> An exception is Without Gods: Toward a History of Disbelief by Mitchell Stephens (another institute project).

“The blog I am writing here, with the connivance of The Institute for the Future of the Book, is an experiment. Our thought is that my book on the history of atheism (eventually to be published by Carroll and Graf) will benefit from an online discussion as the book is being written. Our hope is that the conversation will be joined: ideas challenged, facts corrected, queries answered; that lively and intelligent discussion will ensue. And we have an additional thought: that the web might realize some smidgen of benefit through the airing of this process.”

>>> Searchblog

John Battelle’s daily thoughts on the business and technology of web search, originally set up as a research tool for his now-published book on Google, The Search.

>>> The Long Tail

Similar concept, “a public diary on the way to a book” chronicling “the shift from mass markets to millions of niches.” By current Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson.

>>> Darknet

JD Lasica’s blog on his book about Hollywood’s war against amateur digital filmmakers.

>>> The Technium

Former Wired editor Kevin Kelly is working through ideas for a book:

“As I write I will post here. The purpose of this site is to turn my posts into a conversation. I will be uploading my half-thoughts, notes, self-arguments, early drafts and responses to others’ postings as a way for me to figure out what I actually think.”

>>> End of Cyberspace by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

Pang has some interesting thoughts on blogs as research tools:

“This begins to move you to a model of scholarly performance in which the value resides not exclusively in the finished, published work, but is distributed across a number of usually non-competitive media. If I ever do publish a book on the end of cyberspace, I seriously doubt that anyone who’s encountered the blog will think, “Well, I can read the notes, I don’t need to read the book.” The final product is more like the last chapter of a mystery. You want to know how it comes out.

“It could ultimately point to a somewhat different model for both doing and evaluating scholarship: one that depends a little less on peer-reviewed papers and monographs, and more upon your ability to develop and maintain a piece of intellectual territory, and attract others to it– to build an interested, thoughtful audience.”

* * * * *

This turned out much longer than I’d intended, and yet there’s a lot left to discuss. One question worth mulling over is whether the networked book is really a new idea at all. Don’t all books exist over time within social networks, “linked” to countless other texts? What about the Talmud, the Jewish compendium of law and exigesis where core texts are surrounded on the page by layers of commentary? Is this a networked book? Or could something as prosaic as a phone book chained to a phone booth be considered a networked book?

In our discussions, we have focused overwhelmingly on electronic books within digital networks because we are convinced that this is a major direction in which the book is (or should be) heading. But this is not to imply that the networked book is born in a vacuum. Naturally, it exists in a continuum. And just as our concept of the analog was not fully formed until we had the digital to hold it up against, perhaps our idea of the book contains some as yet undiscovered dimensions that will be revealed by investigating the networked book.

wealth of networks

I was lucky enough to have a chance to be at The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom book launch at Eyebeam in NYC last week. After a short introduction by Jonah Peretti, Yochai Benkler got up and gave us his presentation. The talk was really interesting, covering the basic ideas in his book and delivered with the energy and clarity of a true believer. We are, he says, in a transitional period, during which we have the opportunity to shape our information culture and policies, and thereby the future of our society. From the introduction:

I was lucky enough to have a chance to be at The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom book launch at Eyebeam in NYC last week. After a short introduction by Jonah Peretti, Yochai Benkler got up and gave us his presentation. The talk was really interesting, covering the basic ideas in his book and delivered with the energy and clarity of a true believer. We are, he says, in a transitional period, during which we have the opportunity to shape our information culture and policies, and thereby the future of our society. From the introduction:

This book is offered, then, as a challenge to contemporary legal democracies. We are in the midst of a technological, economic and organizational transformation that allows us to renegotiate the terms of freedom, justice, and productivity in the information society. How we shall live in this new environment will in some significant measure depend on policy choices that we make over the next decade or so. To be able to understand these choices, to be able to make them well, we must recognize that they are part of what is fundamentally a social and political choice—a choice about how to be free, equal, productive human beings under a new set of technological and economic conditions.

During the talk Benkler claimed an optimism for the future, with full faith in the strength of individuals and loose networks to increasingly contribute to our culture and, in certain areas, replace the moneyed interests that exist now. This is the long-held promise of the Internet, open-source technology, and the infomation commons. But what I’m looking forward to, treated at length in his book, is the analysis of the struggle between the contemporary economic and political structure and the unstructured groups enabled by technology. In one corner there is the system of markets in which individuals, government, mass media, and corporations currently try to control various parts of our cultural galaxy. In the other corner there are individuals, non-profits, and social networks sharing with each other through non-market transactions, motivated by uniquely human emotions (community, self-gratification, etc.) rather than profit. Benkler’s claim is that current and future technologies enable richer non-market, public good oriented development of intellectual and cultural products. He also claims that this does not preclude the development of marketable products from these public ideas. In fact, he sees an economic incentive for corporations to support and contribute to the open-source/non-profit sphere. He points to IBM’s Global Services division: the largest part of IBM’s income is based off of consulting fees collected from services related to open-source software implementations. [I have not verified whether this is an accurate portrayal of IBM’s Global Services, but this article suggests that it is. Anecdotally, as a former IBM co-op, I can say that Benkler’s idea has been widely adopted within the organization.]

Further discussion of book will have to wait until I’ve read more of it. As an interesting addition, Benkler put up a wiki to accompany his book. Kathleen Fitzpatrick has just posted about this. She brings up a valid criticism of the wiki: why isn’t the text of the book included on the page? Yes, you can download the pdf, but the texts are in essentially the same environment—yet they are not together. This is one of the things we were trying to overcome with the Gamer Theory design. This separation highlights a larger issue, and one that we are preoccupied with at the institute: how can we shape technology to allow us handle text collaboratively and socially, yet still maintain an author’s unique voice?

the networked book: an increasingly contagious idea

Farrar, Straus and Giroux have ventured into waters pretty much uncharted by a big commercial publisher, putting the entire text of one of their latest titles online in a form designed to be read inside a browser. “Pulse,” a sweeping, multi-disciplinary survey by Robert Frenay of “the new biology” — “the coming age of systems and machines inspired by living things” — is now available to readers serially via blog, RSS or email: two installments per day and once per day on weekends.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux have ventured into waters pretty much uncharted by a big commercial publisher, putting the entire text of one of their latest titles online in a form designed to be read inside a browser. “Pulse,” a sweeping, multi-disciplinary survey by Robert Frenay of “the new biology” — “the coming age of systems and machines inspired by living things” — is now available to readers serially via blog, RSS or email: two installments per day and once per day on weekends.

Naturally, our ears pricked up when we heard they were calling the thing a “networked book” — a concept we’ve been developing for the past year and a half, starting with Kim White’s original post here on “networked book/book as network.” Apparently, the site’s producer, Antony Van Couvering, had never come across if:book and our mad theories before another blogger drew the connection following Pulse’s launch last week. So this would seem to be a case of happy synergy. Let a hundred networked books bloom.

The site is nicely done, employing most of the standard blogger’s toolkit to wire the book into the online discourse: comments, outbound links (embedded by an official “linkologist”), tie-ins to social bookmarking sites, a linkroll to relevant blog carnivals etc. There are also a number of useful tools for exploring the book on-site: a tag cloud, a five-star rating system for individual entries, a full-text concordance, and various ways to filter posts by topic and popularity.

My one major criticism of the Pulse site is that the site is perhaps a little over-accessorized, the design informed less by the book’s inherent structure and themes than by a general enthusiasm for Web 2.0 tools. Pulse clearly was not written for serialization and does not always break down well into self-contained units, so is a blog the ideal reading environment or just the reading environment most readily at hand? Does the abundance of tools perhaps overcrowd the text and intimidate the reader? There has been very little reader commenting or rating activity so far.

But this could all be interpreted as a clever gambit: perhaps FSG is embracing the web with a good faith experiment in sharing and openness, and at the same time relying on the web’s present limitations as a reading interface (and the dribbling pace of syndication — they’ll be rolling this out until November 6) to ultimately drive readers back to the familiar print commodity. We’ll see if it works. In any event, this is an encouraging sign that publishers are beginning to broaden their horizons — light years ahead of what Harper Collins half-heartedly attempted a few months back with one of its more beleaguered titles.

I also applaud FSG for undertaking an experiment like this at a time when the most aggressive movements into online publishing have issued not from publishers but from the likes of Google and Amazon. No doubt, Googlezon’s encroachment into electronic publishing had something to do with FSG’s decision to go ahead with Pulse. Van Couvering urges publishers to take matters into their own hands and start making networked books:

Why get listed in a secondary index when you can be indexed in the primary search results page? Google has been pressuring publishers to make their books available through the Google Books program, arguing (basically) that they’ll get more play if people can search them. Fine, except Google may be getting the play. If you’re producing the content, better do it yourself (before someone else does it).

I hope tht Pulse is not just the lone canary in the coal mine but the first of many such exploratory projects.

Here’s something even more interesting. In a note to readers, Frenay talks about what he’d eventually like to do: make an “open source” version of the book online (incidentally, Yochai Benkler has just done something sort of along these lines with his new book, “The Wealth of Networks” — more on that soon):

At some point I’d like to experiment with putting the full text of Pulse online in a form that anyone can link into and modify, possibly with parallel texts or even by changing or adding to the wording of mine. I like the idea of collaborative texts. I also feel there’s value in the structure and insight that a single, deeply committed author can bring to a subject. So what I want to do is offer my text as an anchor for something that then grows to become its own unique creature. I like to imagine Pulse not just as the book I’ve worked so hard to write, but as a dynamic text that can continue expanding and updating in all directions, to encompass every aspect of this subject (which is also growing so rapidly).

This would come much closer to the networked book as we at the institute have imagined it: a book that evolves over time. It also chimes with Frenay’s theme of modeling technology after nature, repurposing the book as its own intellectual ecosystem. By contrast, the current serialized web version of Pulse is still very much a pre-network kind of book, its structure and substance frozen and non-negotiable; more an experiment in viral marketing than a genuine rethinking of the book model. Whether the open source phase of Pulse ever happens, we have yet to see.

But taking the book for a spin in cyberspace — attracting readers, generating buzz, injecting it into the conversation — is not at all a bad idea, especially in these transitional times when we are continually shifting back and forth between on and offline reading. This is not unlike what we are attempting to do with McKenzie Wark’s “Gamer Theory,” the latest draft of which we are publishing online next month. The web edition of Gamer Theory is designed to gather feedback and to record the conversations of readers, all of which could potentially influence and alter subsequent drafts. Like Pulse, Gamer Theory will eventually be a shelf-based book, but with our experiment we hope to make this networked draft a major stage in its growth, and to suggest what might lie ahead when the networked element is no longer just a version or a stage, but the book itself.

G4M3R 7H30RY: part 4

We’ve moved past the design stage with the GAM3R 7H30RY blog and forum. We’re releasing the book in two formats: all at once (date to be soon decided), in the page card format, and through RSS syndication. We’re collecting user input and feedback in two ways: from comments submitted through the page-card interface, and in user posts in the forum.

The idea is to nest Ken’s work in the social network that surrounds it, made visible in the number of comments and topics posted. This accomplishes something fairly radical, shifting the focus from an author’s work towards the contributions of a work’s readers. The integration between the blog and forums, and the position of the comments in relation to the author’s work emphasizes this shift. We’re hoping that the use of color as an integrating device will further collapse the usual distance between the author and his reading (and writing) public.

To review all the stages that this project has been through before it arrived at this, check out Part I, Part II, and Part III. The design changes show the evolution of our thought and the recognition of the different problems we were facing: screen real estate, reading environment, maintaining the author’s voice but introducing the public, and making it fun. The basic interaction design emerged from those constraints. The page card concept arose from both the form of Ken’s book—a regimented number of paragraphs with limited length—and the constraints of screen real estate (1024×768). The overlapping arose from the physical handling of the ‘Oblique Strategies’ cards, and helps to present all the information on a single screen. The count of pages (five per section, five sections per chapter) is a further expression of the structure that Ken wrote into the book. Comments were lifted from their usual inglorious spot under the writer’s post to be right beside the work. It lends them some additional weight.

We’ve also reimagined the entry point for the forums with the topic pool. It provides a dynamic view of the forums, raising the traditional list into the realm of something energetic, more accurately reflecting the feeling of live conversation. It also helps clarify the direction of the topic discussion with a first post/last post view (visible in the mouseover state below). This simple preview will let users know whether or not a discussion has kept tightly to the subject or spun out of control into trivialities.

We’ve been careful with the niceties: the forum indicator bars turned on their sides to resemble video game power ups; the top of the comments sitting at the same height as the top of their associated page card; the icons representing comments and replies (thanks to famfamfam).

Each of the designed pages changed several times. The page cards have been the most drastically and frequently changed, but the home page went through a significant series of edits in a matter of a few days. As with many things related to design, I took several missteps before alighting on something which seems, in retrospect, perfectly obvious. Although the ‘table of contents’ is traditionally an integrated part of a bound volume, I tried (and failed) to create a different alignment and layout with it. I’m not sure why—it seemed like a good idea at the time. I also wanted to include a hint of the pages to come—unfortunately it just made it difficult for your eye move smoothly across the page. Finally I settled on a simpler concept, one that harmonized with the other layouts, and it all snapped into place.

With that we began the production stage, and we’re making it all real. Next update will be a pre-launch announcement.

the age of amphibians

Momus is a Scottish pop musician, based in Berlin, who writes smart and original things about art and technology. He blogs a wonderful blog called Click Opera — some of the best reading on the web. He wears an eye patch. And he is currently doing a stint as an “unreliable tour guide” at the Whitney Biennial, roving through the galleries, sneaking up behind museum-goers with a bullhorn.

Momus is a Scottish pop musician, based in Berlin, who writes smart and original things about art and technology. He blogs a wonderful blog called Click Opera — some of the best reading on the web. He wears an eye patch. And he is currently doing a stint as an “unreliable tour guide” at the Whitney Biennial, roving through the galleries, sneaking up behind museum-goers with a bullhorn.

A couple of weeks ago, Dan had the bright idea of inviting Momus — seeing as he is currently captive in New York and interested, like us, in the human migration from analog to digital — to visit the institute. Knowing almost nothing about who we are or what we do, he bravely accepted the offer and came over to Brooklyn on one of the Whitney’s dark days and lunched at our table on the customary menu of falafel and babaganoush. Yesterday, he blogged some thoughts about our meeting.

Early on, as happens with most guests, Momus asked something along the lines of: “so what do you mean by ‘future of the book?'” Always an interesting moment, in a generally blue-sky, thinky endeavor such as ours, when you’re forced to pin down some specifics (though in other areas, like Sophie, it’s all about specifics). “Well,” (some clearing of throats) “what we mean is…” “Well, you see, the thing you have to understand is…” …and once again we launch into a conversation that seems to lap at the edges of our table with tide-like regularity. Overheard:

“Well, we don’t mean books in the literal sense…”

“The book at its most essential: an instrument for moving big ideas.”

“A sustained chunk of thought.”

And so it goes… In the end, though, it seems that Momus figured out what we were up to, picking up on our obsession with the relationship between books and conversation:

It seems they’re assuming that the book itself is already over, and that it will survive now as a metaphor for intelligent conversation in networks.

It’s always interesting (and helpful) to hear our operation described by an outside observer. Momus grasped (though I don’t think totally agreed with) how the idea of “the book” might be a useful tool for posing some big questions about where we’re headed — a metaphorical vessel for charting a sea of unknowns. And yet also a concrete form that is being reinvented.

Another choice tidbit from Momus’ report — the hapless traveler’s first encounter with the institute:

I found myself in a kitchen overlooking the sandy back courtyard of a plain clapperboard building on North 7th Street. There were about six men sitting around a kidney-shaped table. One of them was older than the others and looked like a delicate Vulcan. “I expect you’re wondering why you’re here?” he said. “Yes, I’ve been very trusting,” I replied, wondering if I was about to be held hostage by a resistance movement of some kind.

Well, it turned out that the Vulcan was none other than Bob Stein, who founded the amazing Voyager multi-media company, the reference for intelligent CD-ROM publishing in the 90s.

He took this lovely picture of the office:

Interestingly, Momus splices his thoughts on us with some musings on “blooks” (books that began as blogs), commenting on the recently announced winners of lulu.com‘s annual Blooker Prize:

What is a blook? It’s a blog that turns into a book, the way, in evolution, mammals went back into the sea and became fish again. Except they didn’t really do that, although undoubtedly some of us still enjoy a good swim.

And expanding upon this in a comment further down:

…the cunning thing about the concept of the blook is that it posits the book as coming after the blog, not before it, as some evolutionist of media forms would probably do. In this reading, blogs are the past of the book, not its future.

To be that evolutionist for a moment, the “blook” is indeed a curious species, falling somewhere under the genus “networked book,” but at the same time resisting cozy classification, wriggling off the taxonomic hook by virtue of its seemingly regressive character: moving from bits back to atoms; live continuous feedback back to inert bindings and glue. I suspect that “the blook” will be looked back upon as an intriguing artifact of a transitional period, a time when the great apes began sprouting gills.

If we are in fact becoming “post-book,” might this be a regression? A return to an aquatic state of culture, free-flowing and gradually accreting like oral tradition, away from the solid land of paper, print and books? Are we living, then, in an age of amphibians? Hopping in and out of the water, equally at home in both? Is the blog that tentative dip in the water and the blook the return to terra firma?

But I thought the theory of evolution had broken free of this kind of directionality: the Enlightenment idea of progress, the great chain gang of being. Isn’t it all just a long meander, full of forks, leaps and mutations? And so isn’t the future of the book also its past? Might we move beyond the book and yet also stay with it, whether as some defined form or an actual thing in our (webbed) hands? No progress, no regress, just one long continuous motion? Sounds sort of like a conversation…