Adobe just announced the release of Acrobat 8, their PDF production software. To promote it, they hosted three “webinars” on Tuesday to demonstrate some of the new features to the interested public. Your correspondent was there (well, here) to see what glimmers might be discerned about the future of electronic reading.

Who cares about Acrobat?

What does Acrobat have to do with electronic books? You’re probably familiar with Acrobat Reader: it’s the program that opens up PDFs. Acrobat is the “author” program: it lets people make PDFs. This is very important in the world of print design and publishing: probably 90% of the new printed material you see every day goes through Acrobat in some form or another. Acrobat’s not quite as ubiquitous as it once was – newer programs like Adobe InDesign, for example, let designers create PDFs that can be sent to the printer’s without bothering with Acrobat, and it’s easy to make PDFs out of anything in Mac OS X. But Acrobat remains an enormous force in the world of print design.

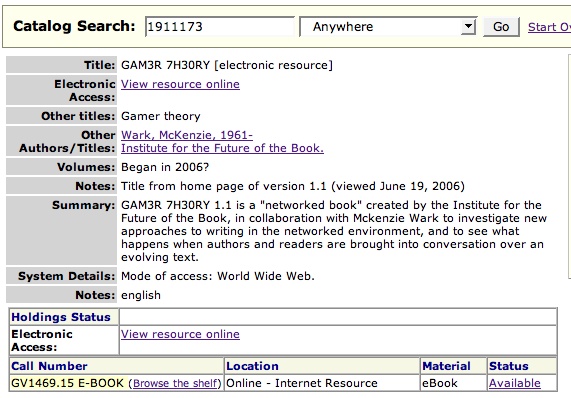

PDF, of course, has been presented as being a suitable format for electronic books; see here for an example. Acrobat provided the ability for publishers to lock down the PDFs that Amazon (for example) sold with DRM; publishers jumped on board. The system wasn’t successful, not least because opening the locked PDFs proved chancey: I have a couple of PDFs I bought during Amazon’s experiment selling them which, on opening, download a lot of “verification information” and then give inscrutable errors. In part because of these troubles, Amazon’s largely abandoned the format – notice their sad-looking ebook store.

Why keep an eye on Acrobat? One reason is because Acrobat 8 is Adobe’s first major release since merging with Macromedia, a union that sent shockwaves across the world of print and web design. Adobe now releases almost most significant programs used in print design. (A single exception is Quark XPress, which has been quietly rolling away towards oblivion of its own accord since around the millennium.) With the acquisition of Macromedia’s web technologies – including Flash and Dreamweaver – Adobe is inching towards a Microsoft-style monopoly of Web design. In short: where Acrobat goes is where Adobe goes; and where Adobe goes is where design goes. And where design goes is where books go, maybe.

So what does Acrobat 8 do?

Acrobat 8 provides a number of updated features that will be useful to people who do pre-press and probably uninteresting to anyone else. They’ve made a number of minor improvements – the U. S. government will be happy to know that they can now use Acrobat to redact information without having to worry about the press looking under their black boxes. You can now use Acrobat to take a bunch of documents (PDF or otherwise) and lump them together into a “bundle”. All nice things, but nothing to get excited about. More DRM than you could shake a stick at, but that’s to be expected.

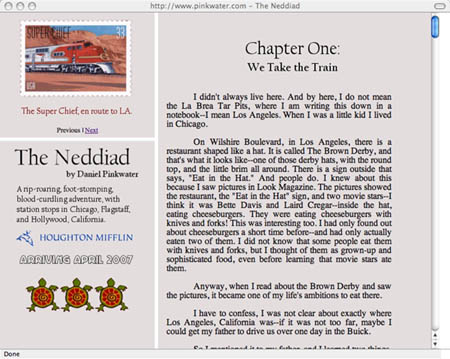

The most interesting thing that Acrobat 8 does – and the reason I’m bringing this up here – is called Acrobat Connect. Acrobat Connect allows users to host web conferences around a document – it was what Adobe was using to hold their “webinars”. (There’s a screenshot to the right; click on the thumbnail for the full-sized image.) These conferences can be joined by anyone with an Internet connection and the Flash plugin. Pages can be turned and annotations can be made by those with sufficient privileges. Audio chatting is available, as is text-based chatting. The whole “conversation” can be recorded for future reference as a Flash-based movie file.

The most interesting thing that Acrobat 8 does – and the reason I’m bringing this up here – is called Acrobat Connect. Acrobat Connect allows users to host web conferences around a document – it was what Adobe was using to hold their “webinars”. (There’s a screenshot to the right; click on the thumbnail for the full-sized image.) These conferences can be joined by anyone with an Internet connection and the Flash plugin. Pages can be turned and annotations can be made by those with sufficient privileges. Audio chatting is available, as is text-based chatting. The whole “conversation” can be recorded for future reference as a Flash-based movie file.

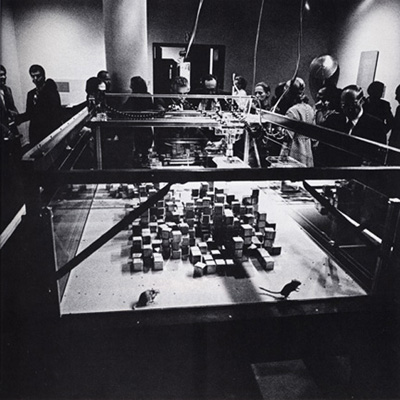

There are a lot of possibilities that this technology suggests: take an electronic book as your source text and you could have an electronic book club. Teachers could work their way through a text with students. You could use it to copy-edit a book that’s being published. A group of people could get together to argue about a particularly interesting blog post. Reading could become a social experience.

But what’s the catch?

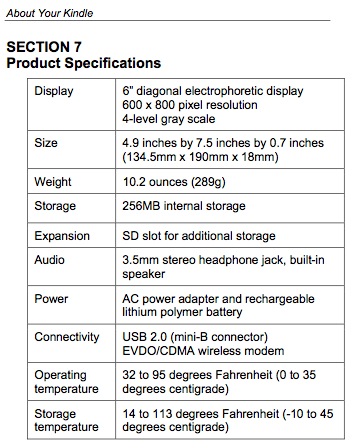

There’s one catch, and it’s a big one: the infrastructure that Acrobat 8 uses: you have to use Adobe’s server, and there’s a price for that. It was suggested that chat-hosting access would be provided for $39 a month or $395 a year. This isn’t entirely a surprise: more and more software companies are trying to rope consumers into subscription-based models. This might well work for Adobe: I’m sure there are plenty of corporations that won’t balk at shelling out $395 a year for what Acrobat Connect offers (plus $449 for the software). Maybe some private schools will see the benefit of doing that. But I can’t imagine, however, that there are going to be many private individuals who will. Much as I’d like to, I won’t.

I’m not faulting Adobe for this stance: they know who butters their bread. But I think it’s worth noting what’s happening here: a divide between the technology available to the corporate world and the general public, and, more specifically, a divide that doesn’t need to exist. Though they don’t have the motive to do so, Adobe could presumably make a version of Acrobat Connect that would work on anyone’s server. This would open up a new realm of possibility in the world of online reading. Instead, what’s going to happen is that the worker bees of the corporate world will find themselves forced to sit through more PowerPoint presentations at their desks.

While a bunch of people reading PowerPoint could be seen as a social reading experience, so much more is possible. We, the public, should be demanding more out of our software.