We’ve just put up a version of a talk Kathleen Fitzpatrick has been giving over the past few months describing the genesis of MediaCommons and its goals for reinventing the peer review process. The paper is in CommentPress — unfortunately not the new version, which we’re still working on (revised estimated release late April), it’s more or less the same build we used for the Iraq Study Group Report. The exciting thing here is that the form of the paper, constructed to solicit reader feedback directly alongside the text, actually enacts its content: radically transparent peer-to-peer review, scholars talking in the open, shepherding the development each other’s work. As of this writing there are already 21 comments posted in the page margins by members of the editorial board (fresh off of last weekend’s retreat) and one or two others. This is an important first step toward what will hopefully become a routine practice in the MediaCommons community.

In less than an hour, Kathleen will be delivering the talk, drawing on some of the comments, at this event at the University of Rochester. Kathleen also briefly introduced the paper yesterday on the MediaCommons blog and posed an interesting question that came out of the weekend’s discussion about whether we should actually be calling this group the “editorial board.” Some interesting discussion ensued. Also check at this: “A First Stab at Some General Principles”.

Category Archives: the_networked_book

amazon starts to close the loop

About two and a half years ago, when the institute was first developing the idea of the “networked book,” we started a thought experiment which tries to imagine what would happen if Marx and Engels published the Communist Manifesto today and posted it to the web in a form which captured the extensive “conversation” that the essay provoked. About a year ago i made an image for a talk which cobbled together thumbnails from various books on Amazon which were related to the Communist Manifesto:

The point of the image was that these books, which are a concrete manifestation of the conversation, exist as isolated islands which at best can reference each other but which are not connected in the way we might imagine in the networked world being born.

Well, amidst all the discussion of the pluses and minuses of both Google and Microsoft book search, for the past two years Amazon has been quietly doing something exciting.

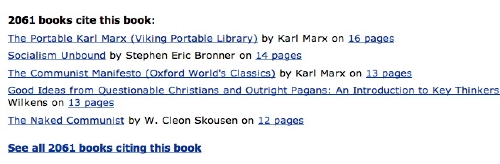

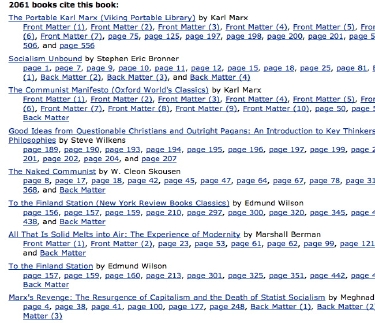

If you go to the Amazon page for an edition of the Communist Manifesto, you’ll see a reference to 2061 books in Amazon’s list which reference the Manifesto with a hot-link to each reference in each of the books.

The only big missing piece is an interactive semantic map with links between all 2061 books.

time out and some of what went into it

A remaindered link that I keep forgetting to post. A couple of weeks back, Time Out London ran a nice little “future of books” feature that makes mention of the Institute. A good chunk of it focuses on On Demand Books, the Espresso book machine and the evolution of print, but it also manages to delve a bit into networked territory, looking at Penguin’s wiki novel project and including a few remarks from me about the yuckiness of e-book hardware and the social aspects of text. Leading up to the article, I had some nice conversations over email and phone with the writer Jessica Winter, most of which of course had no hope of fitting into a ~1300-word piece. And as tends to be the case, the more interesting stuff ended up on the cutting room floor. So I thought I’d take advantage of our laxer space restrictions and throw up for any who are interested some of that conversation.

(Questions are in bold. Please excuse rambliness.)

The other day I was having an interesting conversation with a book editor in which we were trying to determine whether a book is more like a table or a computer; i.e., is a book a really good piece of technology in its present form, or does it need constant rethinking and upgrades, or is it both? Another way of asking this question: Will the regular paper-and-glue book go the way of the stone tablet and the codex, or will it continue to coexist with digital versions? (Sorry, you must get asked this question all the time…)

We keep coming back to this question is because it’s such a tricky one. The simple answer is yes.

The more complicated answer…

When folks at the Institute talk about “the book,” we’re really more interested in the role the book historically has played in our civilization — that is, as the primary vehicle humans use for moving around ideas. In this sense, it seems pretty certain that the future of the book, or to put it more awkwardly, the future of intellectual discourse, is shifting inexorably from printed pages to networked screens.

Predicting hardware is a tougher and ultimately less interesting pursuit. I guess you could say we’re agnostic: unsure about the survival or non-survival of the paper-and-glue book as we are about the success or failure of the latest e-book reading device to hit the market. Still, there’s this strong impulse to try to guess which forms will prevail and which will go extinct. But if you look at the history of media you find that things usually aren’t so clear cut.

It’s actually quite seldom the case that one form flat out replaces another. Far more often the two forms go on existing together, affecting and changing one other in a variety of ways. Photography didn’t kill painting as many predicted it would. Instead it caused a crisis that led to Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism. TV didn’t kill radio but it did usurp radio’s place at the center of the culture and changed the sorts of programming that it made sense for radio to deliver. So far the Internet hasn’t killed TV but there’s no question that it’s bringing about a radical shift in both the production and consumption of television, blurring the line between the two.

The Internet probably won’t kill off books either but it will almost certainly affect what sorts of books get produced, and on the ways in which we read and write them. It’s happening already. Books that look and feel much the same way today as they looked and felt 30 years ago are now almost invariably written on computers with word processing applications, and increasingly, researched or even written on the Web.

Certain things that we used to think of as books — encyclopedias, atlases, phone directories, catalogs — have already been reinvented, and in some cases merged. Other sorts of works, particularly long-form narratives, seem to have a more durable relationship with the printed word. But even here, our relationship with these books is changing as we become more accustomed to new networked forms. Continuous partial attention. Porous boundaries between documents and media. Social and participatory forms of reading. Writing in public. All these things change the very idea of reading and writing, so when you resume an offline mode of doing these things, your perceptions and way of thinking have likely changed.

(A side note. I think this experience of passage back and forth between off and online forms, between analog and digital, is itself significant and for people in our generation, with our general background, is probably the defining state of being. We’re neither immigrant or native. Or to dip into another analogical pot, we’re amphibians.)

As time and technology progress and we move with increasing fluidity between print and digital, we may come to better appreciate the unique affordances of the print book. Looked at one way, the book is an outmoded technology. It lacks the interactivity and interconnectedness of networked communication and is extremely limited in scope when compared with the practically boundless universe of texts and media that exists online. But you could also see this boundedness is its greatest virtue — the focus and structure it brings, enabling sustained thought and contemplation and private intellectual growth. Not to mention archival stability. In these ways the book is a technology that would be hard to improve upon.

John Updike has said that books represent “an encounter, in silence, of two minds.” Does that hold true now, or will it continue to as we continue to rethink the means of production (both technological and intellectual) of books? What are the advantages and disadvantages of a networked book over a book traditionally conceived in that “silent encounter”?

I think I partly answered this question in the last round. But again, as with media forms, so too with ways of reading. Updike is talking about a certain kind of reading, the kind that is best suited to the sorts of things he writes: novels, short stories and criticism. But it would be a mistake to apply this as a universal principle for all books, especially books that are intended as much, if not more, as a jumping off point for discussion as for that silent encounter.

Perhaps the biggest change being brought about by new networked forms of communication is the redefinition of the place of the individual in relation to the collective. The present publishing system very much favors the individual, both in the culture of reverence that surrounds authors and in the intellectual property system that upholds their status as professionals. Updike is at the top of this particular heap and so naturally he defends it as though it were the inviolable natural order.

Digital communication radically clashes with this order: by divorcing intellectual property from physical property (a marriage that has long enabled the culture industry to do business) and by re-situating textual communication in the network, connecting authors and readers in startling ways that rearrange the traditional hiearchies.

What do you think of print-on-demand technology like the Espresso machine? One quibble that I have with it, and it’s probably a lost cause, is that it seems part of the death of browsing (which is otherwise hastened by the demise of the independent bookstore and the rise of the “drive-through” library); opportunities for a chance encounter with a book seem to be lessened. Just curious–has the Institute addressed the importance of browsing at all?

The serendipity of physical browsing would indeed be unfortunate to lose, and there may be some ways of replicating it online. North Carolina State University uses software called Endeca for their online catalog where you pull up a record of a book and you can look at what else is next to it on the physical shelf. But generally speaking browsing in the network age is becoming a social affair. Behavior-derived algorithms are one approach — Amazon’s collaborative filtering system, based on the aggregate clickstreams and purchasing patterns of its customers, is very useful and getting better all the time. Then there’s social bookmarking. There, taxonomy becomes social, serendipity not just a chance encounter with a book or document, but with another reader, or group of readers.

And some other scattered remarks about conversation and the persistent need for editors:

Blogging, comments, message boards, etc… In some ways, the document as a whole is just the seed for the responses. It’s pointing toward a different kind of writing that is more dialogical, and we haven’t really figured it out yet. We don’t yet know how to manage and represent complex conversations in an electronic environment. From a chat room to a discussion forum to a comment stream in a blog post, even to an e-mail thread or a multiparty instant-messaging conversation–it’s just a list of remarks, a linear transcript that flattens the discussion’s spirals, loops and pretzels into a single straight line. In other words, the minute the conversation becomes complex, we become unable to make that complexity readable.

We’ve talked about setting up shop in Second Life and doing an experiment there in modeling conversations. But I’m more interested in finding some way of expanding two-dimensional interfaces into 2.5. We don’t yet know how to represent conversations on a screen once it crosses a certain threshold of complexity.

People gauge comment counts as a measure of the social success of a piece of writing or a video clip. If you look at Huffington Post, you’ll see posts that have 500 comments. Once it gets to that level, it’s sort of impenetrable. It makes the role of filters, of editors and curators–people who can make sound selections–more crucial than ever.

Until recently, publishing existed as a bottleneck model with certain material barriers to publishing. The ability to overleap those barriers was concentrated in a few bottlenecks, with editorial filters to choose what actually got out there. Those material barriers are no longer there; there’s still an enormous digital divide, but for the 1 billion or so people who are connected, those barriers are incredibly low. There’s suddenly a super-abundance of information with no gatekeeper; instead of a bottleneck, we have a deluge. The act of filtering and selecting it down becomes incredibly important. The function that editors serve in the current context will be need to be updated and expanded.

gamer theory 2.0 – visualize this!

Call for participation: Visualize This!

How can we ‘see’ a written text? Do you have a new way of visualizing writing on the screen? If so, then McKenzie Wark and the Institute for the Future of the Book have a challenge for you. We want you to visualize McKenzie’s new book, Gamer Theory.

How can we ‘see’ a written text? Do you have a new way of visualizing writing on the screen? If so, then McKenzie Wark and the Institute for the Future of the Book have a challenge for you. We want you to visualize McKenzie’s new book, Gamer Theory.

Version 1 of Gamer Theory was presented by the Institute for the Future of the Book as a ‘networked book’, open to comments from readers. McKenzie used these comments to write version 2, which will be published in April by Harvard University Press. With the new version we want to extend this exploration of the book in the digital age, and we want you to be part of it.

All you have to do is register, download the v2 text, make a visualization of it (preferably of the whole text though you can also focus on a single part), and upload it to our server with a short explanation of how you did it.

All visualizations will be presented in a gallery on the new Gamer Theory site. Some contributions may be specially featured. All entries will receive a free copy of the printed book (until we run out).

By “visualization” we mean some graphical representation of the text that uses computation to discover new meanings and patterns and enables forms of reading that print can’t support. Some examples that have inspired us:

- Brad Paley’s Text Arc

- Marcos Weskamp’s Newsmap

- Fernanda Viegas’ Wikipedia “History Flow”

- Chirag Mehta’s US Presidential Speeches Tag Cloud

- Kushal Dave’s Exegesis

- Magnus Rembold and Jurgen Spath’s comparative essay visualizations in Total Interaction

- Philip DeCamp, Amber Frid-Jimenez, Jethran Guiness, Deb Roy: “Gist Icons” (pdf)

- CNET News.com’s The Big Picture

- Visuwords online graphical dictionary

- Christopher Collins’ DocuBurst

- Stamen Design’s rendering of Kate Hayles’ Narrating Bits in USC’s Vectors

- Brian Kim Stefans’ The Dreamlife of Letters

- Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries

Understand that this is just a loose guideline. Feel encouraged to break the rules, hack the definition, show us something we hadn’t yet imagined.

All visualizations, like the web version of the text, will be Creative Commons licensed (Attribution-NonCommercial). You have the option of making your code available under this license as well or keeping it to yourself. We encourage you to share the source code of your visualization so that others can learn from your work and build on it. In this spirt, we’ve asked experienced hackers to provide code samples and resources to get you started (these will be made available on the upload page).

Gamer 2.0 will launch around April 18th in synch with the Harvard edition. Deadline for entries is Wednesday, April 11th.

Read GAM3R 7H30RY 1.1.

Download/upload page (registration required):

http://web.futureofthebook.org/gamertheory2.0/viz/

the sea change is coming…

Eons ago, when the institute was just starting out, Ben and I attended a web design conference in Amsterdam where we had the good fortune to chat with Steven Pemberton about the future of the book. Pemberton’s prediction, that “the book is doomed,” was based on the assumption that screen technologies would develop as printer technologies had. When the clunky dot-matrix gave way to the high-quality laser printer, desk top publishing was born and an entire industry changed form almost overnight.

“The book, Pemberton contends, will experience a similar sea-change the moment screen technology improves enough to compete with the printed page.”

This seemed like a logical conclusion. It seemed like the screen technology innovations we were waiting for had to do with resolution and legibility. Over the last two years if:book has reported on digital ink and other innovations that seemed promising. But the fact that we were looking out for a screen technology that could “compete with the printed page,” made it difficult for us to see that the real contender was not page-like at all.

It’s interesting that we made the same assumptions about the structure of the ebook itself. Early ebook systems tried to compete with the book by duplicating conventions like the Table of Contents navigational strategy, and discreet “pages,” that have to be “turned” with the click of a mouse. (And, I’m sorry to report, most contemporary ebooks continue to cling to print book structure). We now understand that networked technologies can interface with book content to create entirely new and revolutionary delivery systems. The experiments the institute has conducted: “Gam3r Th30ry” and the “Iraq Quagmire Project” prove beyond question that the book is evolving and adapting to networked culture.

What kind of screen technology will support this new kind of book? It appears that touch-screen hardware paired with zooming interface software will be the tipping point Pemberton was anticipating. There are many examples of this emerging technology. In particular, I like Jeff Han’s experimental work (his TED presentation is below): Jeff demonstrates an “interface free” touch screen that responds to gesture and lets users navigate through a simulated 3D environment. This technology might allow very small surfaces (like the touchpads on hand-held devices) to act as portals into limitless deep space.

And that brings me around to the real reason the touchscreen zooming interface is the key to the next generation of “books.” It allows users to move into 3D networked space easily and fluently and it gets us beyond the linearity that is the hallmark and the limitation of the paper book. To come into its own, the networked book is going to require three-dimensional visualizations for both content and navigation. Here’s an example of how it might work, imagine the institute’s Iraq Study Group Report in 3D. Main authors would have nodes or “homesites” close to the book with threads connecting them to sections they authored. Co-authors/commentors might have thinner threads that extend out to their, more remotely located, sites. The 3D depiction would allow readers to see “threads” that extend out from each author to everything they have created in digital space. In other words, their entire network would be made visible. Readers could know an author’s body of work in a new way and they could begin to see how collaborative works have been understood and shaped by each contributor. It would be ultimate transparency. It would be absolutely fascinating to see a 3D visualization of other works and deeds by the Iraq Study Groups’ authors, and to “see” the interwoven network spun by Washington’s policy authors. Readers could zoom out to get a sense of each author’s connections. Imagine being able to follow various threads into territories you never would have found via other, more conventional routes. This makes me really curious about what the institute will do in Second Life. I wonder if you can make avatars that act as the nodes for all their threads? Perhaps they could go about like spiders, connecting strands to everything they touch? Hmmm.

But anyway, in my humble opinion the sea change is coming. It’s going to be three-pronged: screen technology, networked content, and 3D visualization. And it’s going to be very, very cool.

bush’s iraq speech: a critical edition

Last month we published an online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report in a new format we’re developing (in-house name is “Comment Press”) that allows readers to enter into conversation with a text and with one another. This was a first step in a creative partnership with Lewis Lapham and Lapham’s Quarterly, a new journal that will look at contemporary issues through the lens of history. Launching only a few days before Christmas, the timing was certainly against us. Only a handful of commenters showed up in those first few days, slowing down almost to a halt as the holiday hibernation period set in. Since New Year’s, however, the site has been picking up momentum and has now amassed a sizable batch of commentary on the Report from a diverse group of respondents including Howard Zinn, Frances FitzGerald and Gary Hart.

While that discussion continues to develop in the Report’s margins, we are following it up with a companion text: the transcript and video of President Bush’s address to the nation last night where he outlined his new strategy for Iraq, presented in a similarly Talmudic fashion with commentary accreting around the central text. To these two documents invited readers and other interested members of the public can continue to append their comments, criticisms and clarifications, “at liberty to find,” in Lapham’s words, “‘the way forward’ in or out of Iraq, back to the future or across the Potomac and into the trees.”

An added feature this time around is that we’re opening the door to general commenters, although with a fairly high barrier to entry. This is an experiment with a more rigorously moderated kind of web discussion and a chance for Lapham and his staff to begin to explore what it means to be editors in the network environment. Anyone is welcome to apply for entry into the discussion by providing a little background on themselves and a sample first comment. If approved by the Lapham’s Quarterly editors (this will all happen within the same day), they will be given a login, at which point they can fire at will on both the speech and the report.

Together these two publications comprise Operation Iraqi Quagmire, a journalistic experiment and a gesture toward a new way of handling public documents in a networked democracy.

***Note: we strongly recommend viewing this on Firefox***

retreat to his study / thoughts for ’07

2006 was a big year for the Institute. We emerged as a sort of publishing lab, a place for authors and readers to rethink books in the digital age — both theoretically (in the wide-ranging dicussions on this blog) and practically (in hands-on experimentation). The project that got things rolling on the practical end — and which is now wrapping up its current phase and down-shifting tempo — was undoubtedly Mitch Stephens’ book blog Without Gods. Like many of our experiments, this one emerged not by some grand design but through an offhand suggestion, when we thought we were headed somewhere else.

Two Novembers ago Bob and I were meeting Mitch for lunch at a cafe near NYU to chat about blogging and its impact on the news media (remember that Mitch, though lately preoccupied with the history of atheism, is a professor in the journalism program at NYU). We were preparing to host a meeting at USC of leading academic bloggers to discuss how scholars were beginning to use blogs to enliven discourse in their fields, and how certain ones (like Juan Cole and PZ Myers) were reaching a general readership, bringing their knowledge to bear on media coverage of subjects like Iraq or the intelligent design movement.

At one point during the lunch it came up that Mitch was in the early stages of researching a new book on nonbelievers and the idea was tossed out — I suppose in the spirit of the discussion — that he start a blog to see how the writing process might be opened up in real time, engaging readers in dialog. Mitch seemed intrigued (guardedly) and said he’d think it over.

A few weeks later, back from a fascinating time in LA, I was pleasantly surprised to receive an email from Mitch saying that he’d been considering the blog idea and wanted to give it a shot. We’d returned from the USC meeting pretty charged up by the discussion we had there and convinced that blogging represented at least the primitive beginnings of a major reorganization of scholarly and public discourse. But we were at a loss as to what our small outfit could do to help. Mitch’s email, if not the answer to all our questions, seemed like a great way to get our hands dirty making a tangible product and would perhaps help us to figure out our next steps. We had a few brainstorm meetings, pulled together a basic design, and Without Gods was born.

A year on, I think it’s safe to say that it’s been a success — actually a turning point for us in balancing the proportions in our work of theoretical pondering to practical experimentation. It’s somewhat ironic that the most substantial thing to come out of the academic blogging inquiry was slightly to the side of the initial question, and conceived before the meeting. But that’s often how things occur. Questions lead to other questions. Without Gods led to Gamer Theory, Gamer Theory led to Holy of Holies, which in turn led to the Iraq Study Group Report. Which I suppose all in some way stems from the academic blogging inquiry and the many tributaries it opened up. MediaCommons is steeped in a belief in the importance of vibrant and visible conversation among scholars in forms ranging from the blog to the networked book — values laid out in the original USC gathering, and developed through our work on Without Gods and beyond.

Now, as hinted before, Mitch has decided it’s time to retreat to his study in order to bring the book to fruition — offline. As he forges ahead, however, he’ll carry with him the echoes — and the archive — of the past year’s discussions.

After a year of mostly daily blogging on this site, I am cutting back.

As most of you know, I am writing a book on the history of disbelief for Carroll and Graf. The blog — produced while working on the book — was an experiment conceived by the Institute for the Future of the Book. It has been a success. I have been benefiting from informed and insightful comments by readers of the blog as I’ve tested some ideas from this book and explored some of their connections to contemporary debates.

I may continue to post sporatically here, but now it seems time to retreat to my study to digest what I’ve learned, polish my thoughts and compose the rest of the narrative. The trick will be accomplishing that without losing touch with those – commenters or just silent readers – who are interested in this project….do try to check back here once in a while. There will be some updates and, perhaps, some new experiments.

New experiments such as “Holy of Holies,” a paper that Mitch delivered last month before an NYU working group on “Secularism, Religious Authority, and the Mediation of Knowledge” (it’s still humming with over a hundred comments). Although blog posting will be sporadic, futureofthebook.org/mitchellstephens will remain the internet hub for Mitch’s book, sections of which may appear in draft state in a format similar to the NYU paper (depending on where Mitch, and his publisher, are at). If you’d like to be notified directly of such developments, there’s a form on the site where you can enter your email address.

Thanks, Mitch, and best of luck. We couldn’t have asked for a better partner in exploring this transitional territory. I hope 2007 proves to be as interesting and as healthy a mix of thinking and doing, for you and for us.

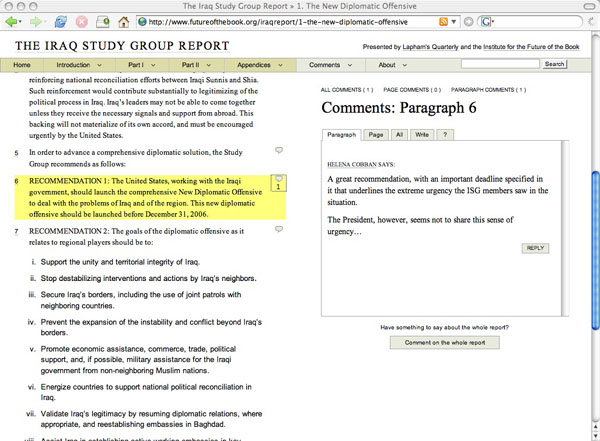

live, on the web, it’s the iraq study group report!

Since leaving Harper’s last spring, Lewis Lapham has been developing plans for a new journal, Lapham’s Quarterly, which will look at important contemporary subjects (one per issue) through the lens of history. Not long ago, Lewis approached the Institute about helping him and his colleagues to develop a web component of the Quarterly, which he imagined as a kind of unorthodox news site where history and source documents would serve as a decoder ring for current events — a trading post of ideas, facts, and historical parallels where readers would play a significant role in piecing together the big picture. To begin probing some of the possibilities for this collaboration, we came up with an exciting and timely experiment: we’ve taken the granular commenting format that we hacked together just a few weeks ago for Mitch Stephens’ paper and plugged in the Iraq Study Group Report. The Lapham crew, for their part, have taken their first editorial plunge into the web, using their broad print network to assemble an astonishing roster of intellectual heavyweights to collectively annotate the text, paragraph by paragraph, live on the site. Here’s more from Lewis:

As expected and in line with standard government practice, the report issued by the Iraq Study Group on December 6th comes to us written in a language that guards against the crime of meaning–a document meant to be admired as a praise-worthy gesture rather than understood as a clear statement of purpose or an intelligible rendition of the facts. How then to read the message in the bottle or the handwriting on the wall?

Lapham’s Quarterly and the Institute for the Future of the Book answers the question with a new form of discussion and critique– an annotated edition of the ISG Report on a website programmed to that specific purpose, evolving over the course of the next three weeks into a collaborative illumination of an otherwise black hole. What you have before you is the humble beginnings of that effort–the first few marginal notes and commentaries furnished by what will eventually be a large number of informed sources both foreign and domestic (historians, military officers, politicians, intelligence operatives, diplomats, some journalists), invited to amend, correct, augment or contradict any point in the text seemingly in need of further clarification or forthright translation into plain English.

As the discussion adds to the number of its participants so also it will extend the reach of its memory and enlarge its spheres of reference. What we hope will take shape on short notice and in real time is the publication of a report that should prove to be a good deal more instructive than the one distributed to the members of Congress and the major news media.

Being at the very beginning of the experiment, what you’ll see on the site today is more or less a blank slate. Our hope is that in the days and weeks ahead, a lively conversation will begin to bubble up in the pages of the report — a kind of collaborative marginalia on a grand scale — mounting toward Bush’s big Iraq strategy speech next month. Around that time, the Lapham’s editors will open up commenting to the public. Until then, here are just some of the people we expect to participate: Anthony Arnove, Helena Cobban, Joshua Cohen, Jean Daniel, Raghida Dergham, Joan Didion, Mark Danner, Barbara Ehrenrich, Daniel Ellsberg, Tom Engelhardt, Stanley Fish, Robert Fisk, Eric Foner, Christopher Hitchens, Rashid Khalidi, Chalmers Johnson, Donald Kagan, Kanan Makiya, William Polk, Walter Russel Mead, Karl Meyer, Ralph Nader, Gianni Riotta, M.J. Rosenberg, Gary Sick, Matthew Stevenson, Frances Stonor, Lally Weymouth, and Wayne White.

Not too shabby.

The form is still very much in the R&D phase, but we’ve made significant improvements since the last round. Add this to your holiday reading stack and watch how it develops.

(We strongly recommend viewing the site in Firefox.)

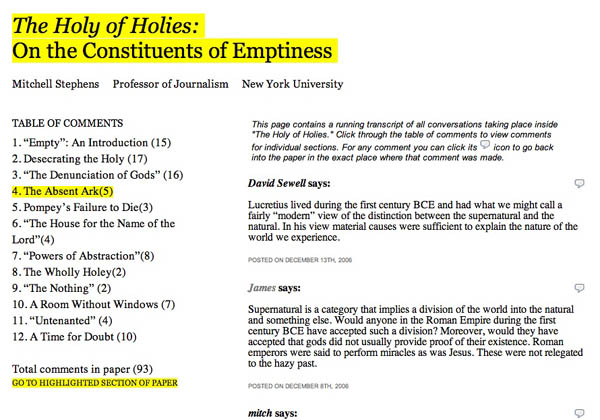

table of comments

Yesterday Bud Parr made the following suggestion regarding the design of Mitch Stephens’ networked paper, “The Holy of Holies”:

I think the site would benefit from something right up front highlighting the most recent exchange of comments and/or what’s getting the most attention in terms of comments.

It just so happens that we’ve been cooking up something that does more or less what he describes: a simple meta comment page, or “table of comments,” displaying a running transcript of all the conversations in the site filtered by section. You can get to it from a link on the front page next to the total comment count for the paper (as of this writing there are 93).

It’s an interesting way to get into the text: through what people are saying about it. Any other ideas of how something like this could work?

2 – dimensions just aren’t enough

We’re burning way too much midnight oil this weekend trying to ready a networked version of the Iraq Study Group report for release next week. We’ll introduce the project itself in a few days, but right now i just want to mention that i think we’re about at the end of our ability to organize these very complex reading/writing projects using the 2-dimensional design constraints inherited from print. Ben came to the same conclusion in his recent post inspired by the difficulty of designing the site for Mitch Stephens’ paper, Holy of Holies. My first resolution for 2007 is to try an experiments building a networked book inside of Second Life or some other three-dimensional environment.