Over at Teleread, David Rothman has a pair of posts about Google’s new desktop RSS reader and a couple of new technologies for creating “offline web applications” (Google Gears and Adobe Apollo), tying them all together into an interesting speculation about the possibility of offline networked books. This would mean media-rich, hypertextual books that could cache some or all of their remote elements and be experienced whole (or close to whole) without a network connection, leveraging the local power of the desktop. Sophie already does this to a limited degree, caching remote movies for a brief period after unplugging.

Electronic reading is usually prey to a million distractions and digressions, but David’s idea suggests an interesting alternative: you take a chunk of the network offline with you for a more sustained, “bounded” engagement. We already do this with desktop email clients and RSS readers, which allow us to browse networked content offline. This could be expanded into a whole new way of reading (and writing) networked books. Having your own copy of a networked document. Seems this should be a basic requirement for any dedicated e-reader worth its salt, to be able to run rich web applications with an “offline” option.

Category Archives: the_networked_book

visual amazon browser

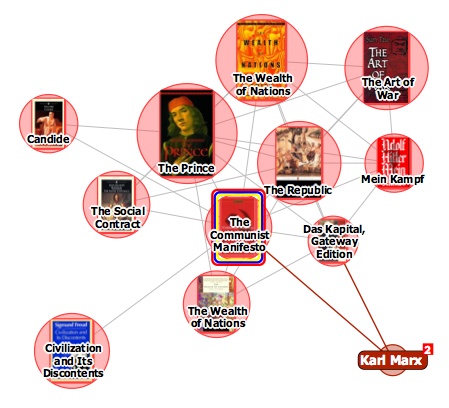

The interface design firm TouchGraph recently released a free visual browsing tool for Amazon’s books, movies, music and electronics inventories. My first thought was, aha, here’s a tool that can generate an image of Bob’s thought experiment, which reimagines The Communist Manifesto as a networked book, connected digitally to all the writings it has influenced and all the commentaries that have been written about it. Alas no.

It turns out that relations between items in the TouchGraph clusters are based not on citations across texts but purely on customer purchase patterns, the data that generates the “customers who bought this item also bought” links on Amazon pages. The results, consequently, are a tad shallow. Above you see The Communist Manifesto situated in a small web of political philosophy heavyweights, an image that reveals more about Amazon’s algorithmically derived recommendations than any actual networks of discourse.

TouchGraph has built a nice tool, and I’m sure with further investigation it might reveal interesting patterns in Amazon reading (and buying) behaviors (in the electronics category, it could also come in handy for comparison shopping). But I’d like to see a new verion that factors in citation indexes for books – data that Amazon already provides for many of its titles anyway. They could also look at user-supplied tags, Listmania lists, references from reader reviews etc. And perhaps with the option to view clusters across media types, not simply broken down into book, movie and music categories.

time machine

The other day, a bunch of us were looking at this new feature promised for Leopard, the next iteration of the Mac operating system, and thinking about it as a possible interface for document versioning.

I’ve yet to find something that does this well. Wikis and and Google Docs give you chronological version lists. In Microsoft Word, “track changes” integrates editing history within the surface of the text, but it’s ugly and clunky. Wikipedia has a version comparison feature, which is nice, but it’s only really useful for scrutinizing two specific passages.

If a document could be seen to have layers, perhaps in a similar fashion to Apple’s Time Machine, or more like Gamer Theory‘s stacks of cards, it would immediately give the reader or writer a visual sense of how far back the text’s history goes – not so much a 3-D interface as 2.5-D. Sifting through the layers would need to be easy and tactile. You’d want ways to mark, annotate or reference specific versions, to highlight or suppress areas where text has been altered, to pull sections into a comparison view. Perhaps there could be a “fade” option for toggling between versions, slowing down the transition so you could see precisely where the text becomes liquid, the page in effect becoming a semi-transparent membrane between two versions. Or “heat maps” that highlight, through hot and cool hues, the more contested or agonized-over sections of the text (as in the Free Software Foundations commentable drafts of the GNU General Public License).

And of course you’d need to figure out comments. When the text is a moving target, which comments stay anchored to a specific version, and which ones get carried with you further through the process? What do you bring with you and what do you leave behind?

the people’s card catalog (a thought)

New partners and new features. Google has been busy lately building up Book Search. On the institutional end, Ghent, Lausanne and Mysore are among the most recent universities to hitch their wagons to the Google library project. On the user end, the GBS feature set continues to expand, with new discovery tools and more extensive “about” pages gathering a range of contextual resources for each individual volume.

Recently, they extended this coverage to books that haven’t yet been digitized, substantially increasing the findability, if not yet the searchability, of thousands of new titles. The about pages are similar to Amazon’s, which supply book browsers with things like concordances, “statistically improbably phrases” (tags generated automatically from distinct phrasings in a text), textual statistics, and, best of all, hot-linked lists of references to and from other titles in the catalog: a rich bibliographic network of interconnected texts (Bob wrote about this fairly recently). Google’s pages do much the same thing but add other valuable links to retailers, library catalogues, reviews, blogs, scholarly resources, Wikipedia entries, and other relevant sites around the net (an example). Again, many of these books are not yet full-text searchable, but collecting these resources in one place is highly useful.

It makes me think, though, how sorely an open source alternative to this is needed. Wikipedia already has reasonably extensive articles about various works of literature. Library Thing has built a terrific social architecture for sharing books. There are a great number of other freely accessible resources around the web, scholarly database projects, public domain e-libraries, CC-licensed collections, library catalogs.

Could this be stitched together into a public, non-proprietary book directory, a People’s Card Catalog? A web page for every book, perhaps in wiki format, wtih detailed bibliographic profiles, history, links, citation indices, social tools, visualizations, and ideally a smart graphical interface for browsing it. In a network of books, each title ought to have a stable node to which resources can be attached and from which discussions can branch. So far Google is leading the way in building this modern bibliographic system, and stands to turn the card catalogue of the future into a major advertising cash nexus. Let them do it. But couldn’t we build something better?

the encyclopedia of life

E. O. Wilson, one of the world’s most distinguished scientists, professor and honorary curator in entomology at Harvard, promoted his long-cherished idea of The Encyclopedia of Life, as he accepted the TED Prize 2007.

The reason behind his project is the catastrophic human threat to our biosphere. For Wilson, our knowledge of biodiversity is so abysmally incomplete that we are at risk of losing a great deal of it even before we discover it. In the US alone, of the 200,000 known species, only about 15% have been studied well enough to evaluate their status. In other words, we are “flying blindly into our environmental future.” If we don’t explore the biosphere properly, we won’t be able to understand it and competently manage it. In order to do this, we need to work together to help create the key tools that are needed to inspire preservation and biodiversity. This vast enterprise, equivalent of the human genome project, is possible today thanks to scientific and technological advances. The Encyclopedia of Life is conceived as a networked project to which thousands of scientists, and amateurs, form around the world can contribute. It is comprised of an indefinitely expandable page for each species, with the hope that all key information about life can be accessible to anyone anywhere in the world. According to Wilson’s dream, this aggregation, expansion, and communication of knowledge will address transcendent qualities in the human consciousness and will transform the science of biology in ways of obvious benefit to humans as it will inspire present, and future, biologists to continue the search for life, to understand it, and above all, to preserve it.

The first big step in that dream came true on May 9th when major scientific institutions, backed by a funding commitment led by the MacArthur Foundation, announced a global effort to launch the project. The Encyclopedia of Life is a collaborative scientific effort led by the Field Museum, Harvard University, Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole), Missouri Botanical Garden, Smithsonian Institution, and Biodiversity Heritage Library, and also the American Museum of Natural History (New York), Natural History Museum (London), New York Botanical Garden, and Royal Botanic Garden (Kew). Ultimately, the Encyclopedia of Life will provide an online database for all 1.8 million species now known to live on Earth.

As we ponder about the meaning, and the ways, of the network; a collective place that fosters new kinds of creation and dialogue, a place that dehumanizes, a place of destruction or reconstruction of memory where time is not lost because is always available, we begin to wonder about the value of having all that information at our fingertips. Was it having to go to the library, searching the catalog, looking for the books, piling them on a table, and leafing through them in search of information that one copied by hand, or photocopied to read later, a more meaningful exercise? Because I wrote my dissertation at the library, though I then went home and painstakingly used a word processor to compose it, am not sure which process is better, or worse. For Socrates, as Dan cites him, we, people of the written word, are forgetful, ignorant, filled with the conceit of wisdom. However, we still process information. I still need to read a lot to retain a little. But that little, guides my future search. It seems that E.O. Wilson’s dream, in all its ambition but also its humility, is a desire to use the Internet’s capability of information sharing and accessibility to make us more human. Looking at the demonstration pages of The Encyclopedia of Life, took me to one of my early botanical interests: mushrooms, and to the species that most attracted me when I first “discovered” it, the deadly poisonous Amanita phalloides, related to Alice in Wonderland’s Fly agaric, Amanita muscaria, which I adopted as my pen name for a while. Those fabulous engravings that mesmerized me as a child, brought me understanding as a youth, and pleasure as a grown up, all came back to me this afternoon, thanks to a combination of factors that, somehow, the Internet catalyzed for me.

As we ponder about the meaning, and the ways, of the network; a collective place that fosters new kinds of creation and dialogue, a place that dehumanizes, a place of destruction or reconstruction of memory where time is not lost because is always available, we begin to wonder about the value of having all that information at our fingertips. Was it having to go to the library, searching the catalog, looking for the books, piling them on a table, and leafing through them in search of information that one copied by hand, or photocopied to read later, a more meaningful exercise? Because I wrote my dissertation at the library, though I then went home and painstakingly used a word processor to compose it, am not sure which process is better, or worse. For Socrates, as Dan cites him, we, people of the written word, are forgetful, ignorant, filled with the conceit of wisdom. However, we still process information. I still need to read a lot to retain a little. But that little, guides my future search. It seems that E.O. Wilson’s dream, in all its ambition but also its humility, is a desire to use the Internet’s capability of information sharing and accessibility to make us more human. Looking at the demonstration pages of The Encyclopedia of Life, took me to one of my early botanical interests: mushrooms, and to the species that most attracted me when I first “discovered” it, the deadly poisonous Amanita phalloides, related to Alice in Wonderland’s Fly agaric, Amanita muscaria, which I adopted as my pen name for a while. Those fabulous engravings that mesmerized me as a child, brought me understanding as a youth, and pleasure as a grown up, all came back to me this afternoon, thanks to a combination of factors that, somehow, the Internet catalyzed for me.

another chapter in the prehistory of the networked book

A quick post to note that there’s an interesting article at the Brooklyn Rail by Dara Greenwald on the early history of video collectives. I know next to nothing about the history of video, but it’s a fascinating piece & her description of the way video collectives worked in the early 1970s is eye-opening. In particular, the model of interactivity they espoused resonates strongly with the way media works across the network today. An excerpt:

Many of the 1970s groups worked in a style termed “street tapes,” interviewing passersby on the streets, in their homes, or on doorsteps. As Deirdre Boyle writes in Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited (1997), the goal of street tapes was to create an “interactive information loop” with the subject in order to contest the one-way communication model of network television. One collective, The People’s Video Theater, were specifically interested in the social possibilities of video. On the streets of NYC, they would interview people and then invite them back to their loft to watch the tapes that night. This fit into the theoretical framework that groups were working with at the time, the idea of feedback. Feedback was considered both a technological and social idea. As already stated, they saw a danger in the one-way communication structure of mainstream television, and street tapes allowed for direct people-to-people communications. Some media makers were also interested in feeding back the medium itself in the way that musicians have experimented with amp feedback; jamming communication and creating interference or noise in the communications structures.

Video was also used to mediate between groups in disagreement or in social conflict. Instead of talking back to the television, some groups attempted to talk through it. One example of video’s use as a mediation tool in the early 70s was a project of the students at the Media Co-op at NYU. They taped interviews with squatters and disgruntled neighbors and then had each party view the other’s tape for better understanding. The students believed they were encouraging a more “real” dialogue than a face-to-face encounter would allow because the conflicting parties had an easier time expressing their position and communicating when the other was not in the same room.

Is YouTube being used this way? The tools the video collectives were using are now widely available; I’m sure there are efforts like this out there, but I don’t know of them.

Greenwald’s piece also appears in Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority, a collection edited by Josh MacPhee and Erik Reuland which looks worthwhile.

chromograms: visualizing an individual’s editing history in wikipedia

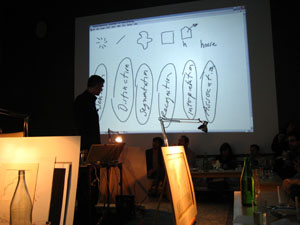

The field of information visualization is cluttered with works that claim to illuminate but in fact obscure. These are what Brad Paley calls “write-only” visualizations. If you put information in but don’t get any out, says Paley, the visualization has failed, no matter how much it dazzles. Brad discusses these matters with the zeal of a spiritual seeker. Just this Monday, he gave a master class in visualization on two laptops, four easels, and four wall screens at the Institute’s second “Monkeybook” evening at our favorite video venue in Brooklyn, Monkeytown. It was a scintillating performance that left the audience in a collective state of synaptic arrest.

Jesse took some photos:

We stand at a crucial juncture, Brad says, where we must marshal knowledge from the relevant disciplines — design, the arts, cognitive science, engineering — in order to build tools and interfaces that will help us make sense of the huge masses of information that have been dumped upon us with the advent of computer networks. All the shallow efforts passing as meaning, each pretty piece of infoporn that obfuscates as it titillates, is a drag on this purpose, and a muddying of the principles of “cognitive engineering” that must be honed and mastered if we are to keep a grip on the world.

With this eloquent gospel still echoing in my brain, I turned my gaze the next day to a new project out of IBM’s Visual Communication Lab that analyzes individuals’ editing histories in Wikipedia. This was produced by the same team of researchers (including the brilliant Fernanda Viegas) that built the well known History Flow, an elegant technique for visualizing the revision histories of Wikipedia articles — a program which, I think it’s fair to say, would rate favorably on the Paley scale of readability and illumination. Their latest effort, called “Chromograms,” hones in the activities of individual Wikipedia editors.

The IBM team is interested generally in understanding the dynamics of peer to peer labor on the internet. They’ve focused on Wikipedia in particular because it provides such rich and transparent records of its production — each individual edit logged, many of them discussed and contextualized through contributors’ commentary. This is a juicy heap of data that, if placed under the right set of lenses, might help make sense of the massively peer-produced palimpsest that is the world’s largest encyclopedia, and, in turn, reveal something about other related endeavors.

Their question was simple: how do the most dedicated Wikipedia contributors divvy up their labor? In other words, when someone says, “I edit Wikipedia,” what precisely do they mean? Are they writing actual copy? Fact checking? Fixing typos and syntactical errors? Categorizing? Adding images? Adding internal links? External ones? Bringing pages into line with Wikipedia style and citation standards? Reverting vandalism?

All of the above, of course. But how it breaks down across contributors, and how those contributors organize and pace their work, is still largely a mystery. Chromograms shed a bit of light.

For their study, the IBM team took the edit histories of Wikipedia administrators: users to whom the community has granted access to the technical backend and who have special privileges to protect and delete pages, and to block unruly users. Admins are among the most active contributors to Wikipedia, some averaging as many as 100 edits per day, and are responsible more than any other single group for the site’s day-to-day maintenance and governance.

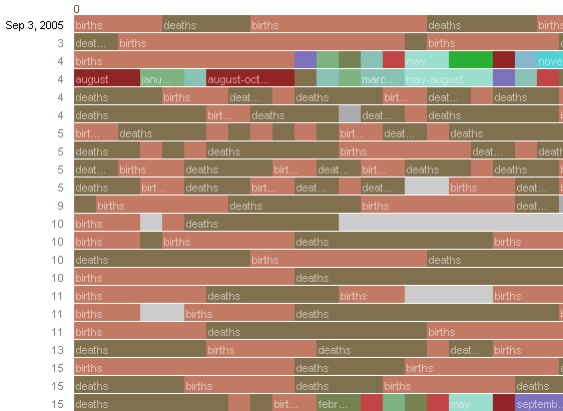

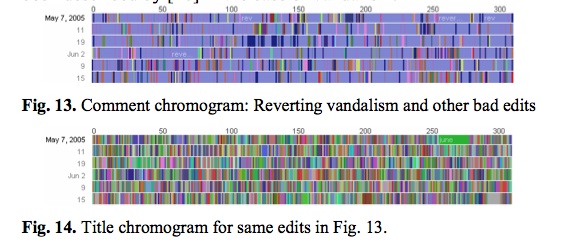

What the researches essentially did was run through the edit histories with a fine-toothed, color-coded comb. A chromogram consists of multiple rows of colored tiles, each tile representing a single edit. The color of the tile corresponds with the first letter of the text in the edit, or in the case of “comment chromograms,” the first letter of the user’s description of their edit. Colors run through the alphabet, starting with numbers 1-10 in hues of gray and then running through the ROYGBIV spectrum, A (red) to violet (Z).

It’s a simple system, and one that seems arbitrary at first, but it accomplishes the important task of visually separating editorial actions, and making evident certain patterns in editors’ workflow.

Much was gleaned about the way admins divide their time. Acvitity often occurs in bursts, they found, either in response to specific events such as vandalism, or in steady, methodical tackling of nitpicky, often repetitive, tasks — catching typos, fixing wiki syntax, labeling images etc. Here’s a detail of a chromogram depicting an administrator’s repeated entry of birth and death information on a year page:

The team found that this sort of systematic labor was often guided by lists, either to-do lists in Wikiprojects, or lists of information in articles (a list of naval ships, say). Other times, an editing spree simply works progressively through the alphabet. The way to tell? Look for rainbows. Since the color spectrum runs A to Z, rainbow patterned chromograms depict these sorts of alphabetically ordered tasks. As in here:

This next pair of images is almost moving. The top one shows one administrator’s crusade against a bout of vandalism. Appropriately, he’s got the blues, blue corresponding with “r” for “revert.” The bottom image shows the same edit history but by article title. The result? A rainbow. Vandalism from A to Z.

Chromograms is just one tool that sheds light on a particular sort of editing activity in Wikipedia — the fussy, tedious labors of love that keep the vast engine running smoothly. Visualizing these histories goes some distance toward explaining how the distributed method of Wikipedia editing turns out to be so efficient (for a far more detailed account of what the IBM team learned, it’s worth reading this pdf). The chromogram technique is probably too crude to reveal much about the sorts of editing that more directly impact the substance of Wikipedia articles, but it might be a good stepping stone.

Learning how to read all the layers of Wikipedia is necessarily a mammoth undertaking that will require many tools, visualizations being just one of them. High-quality, detailed ethnographies are another thing that could greatly increase our understanding. Does anyone know of anything good in this area?

gamer theory 2.0

…is officially live! Check it out. Spread the word.

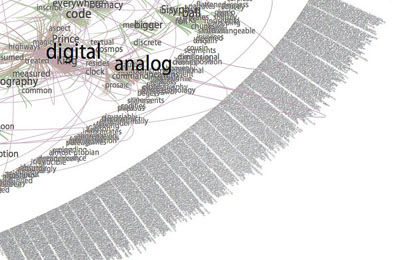

I want to draw special attention to the Gamer Theory TextArc in the visualization gallery – a graphical rendering of the book that reveals (quite beautifully) some of the text’s underlying structures.

Gamer Arc detail

TextArc was created by Brad Paley, a brilliant interaction designer based in New York. A few weeks ago, he and Ken Wark came over to the Institute to play around with the Gamer Theory in TextArc on a wall display:

Ken jotted down some of his thoughts on the experience: “Brad put it up on the screen and it was like seeing a diagram of my own writing brain…” Read more here (then scroll down partway).

starting bottom-left, counter-clockwise: Ken, Brad, Eddie, Bob

More thoughts about all of this to come. I’ve spent the past two days running around like a madman at the Digital Library Federation Spring Forum in Pasadena, presenting our work (MediaCommons in particular), ducking in and out of sessions, chatting with interesting folks, and pounding away at the Gamer site — inserting footnote links, writing copy, generally polishing. I’m looking forward to regrouping in New York and processing all of this.

Thanks, Florian Brody for the photos.

Oh, and here is the “official” press/blogosphere release. Circulate freely:

The Institute for the Future of the Book is pleased to announce a new edition of the “networked book” Gamer Theory by McKenzie Wark. Last year, the Institute published a draft of Wark’s path-breaking critical study of video games in an experimental web format designed to bring readers into conversation around a work in progress. In the months that followed, hundreds of comments poured in from gamers, students, scholars, artists and the generally curious, at times turning into a full-blown conversation in the manuscript’s margins. Based on the many thoughtful contributions he received, Wark revised the book and has now published a print edition through Harvard University Press, which contains an edited selection of comments from the original website. In conjunction with the Harvard release, the Institute for the Future of the Book has launched a new Creative Commons-licensed, social web edition of Gamer Theory, along with a gallery of data visualizations of the text submitted by leading interaction designers, artists and hackers. This constellation of formats — read, read/write, visualize — offers the reader multiple ways of discovering and building upon Gamer Theory. A multi-mediated approach to the book in the digital age.

http://web.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/

More about the book:

Ever get the feeling that life’s a game with changing rules and no clear sides, one you are compelled to play yet cannot win? Welcome to gamespace. Gamespace is where and how we live today. It is everywhere and nowhere: the main chance, the best shot, the big leagues, the only game in town. In a world thus configured, McKenzie Wark contends, digital computer games are the emergent cultural form of the times. Where others argue obsessively over violence in games, Wark approaches them as a utopian version of the world in which we actually live. Playing against the machine on a game console, we enjoy the only truly level playing field–where we get ahead on our strengths or not at all.

Gamer Theory uncovers the significance of games in the gap between the near-perfection of actual games and the highly imperfect gamespace of everyday life in the rat race of free-market society. The book depicts a world becoming an inescapable series of less and less perfect games. This world gives rise to a new persona. In place of the subject or citizen stands the gamer. As all previous such personae had their breviaries and manuals, Gamer Theory seeks to offer guidance for thinking within this new character. Neither a strategy guide nor a cheat sheet for improving one’s score or skills, the book is instead a primer in thinking about a world made over as a gamespace, recast as an imperfect copy of the game.

——————-

The Institute for the Future of the Book is a small New York-based think tank dedicated to inventing new forms of discourse for the network age. Other recent publishing experiments include an annotated online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report (with Lapham’s Quarterly), Without Gods: Toward a History of Disbelief (with Mitchell Stephens, NYU), and MediaCommons, a digital scholarly network in media studies. Read the Institute’s blog, if:book. Inquiries: curator [at] futureofthebook [dot] org

McKenzie Wark teaches media and cultural studies at the New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College in New York City. He is the author of several books, most recently A Hacker Manifesto (Harvard University Press) and Dispositions (Salt Publishing).

gamer theory 2.0 (beta)

The new Gamer Theory site is up, though for the next 24 hours we’re considering it beta. It’s all pretty much there except for some last bits and pieces (pop-up textual notes, a few explanatory materials, one or two pieces for the visualization gallery, miscellaneous tweaks). By all means start poking around and posting comments.

The project now has a portal page that links you to the constitutent parts: the Harvard print edition, two networked web editions (1.1 and 2.0), a discussion forum, and, newest of all, a gallery of text visualizations including a customized version of Brad Paley’s “TextArc” and a fascinating prototype of a progam called “FeatureLens” from the Human-Computer Interaction Lab at the University of Maryland. We’ll make a much bigger announcement about this tomorrow. For now, consider the site softly launched.

dismantling the book

Peter Brantley relates the frustrating experience of trying to hunt down a particular passage in a book and his subsequent painful collision with the cold economic realities of publishing. The story involves a $58 paperback, a moment of outrage, and a venting session with an anonymous friend in publishing. As it happens, the venting turned into some pretty fascinating speculative musing on the future of books, some of which Peter has reproduced on his blog. Well worth a read.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

Amazon already provides a by-the-page or by-the-chapter option for certain titles through its “Pages” program. Google presumably will hammer out some deals with publishers and offer a similar service before too long. Peter Osnos’ Caravan Project includes individual chapter downloads and print-on-demand as part of the five-prong distribution standard it is promoting throughout the industry. If this catches on, it will open up a plethora of options for readers but it might also unvravel the very notion of what a book is. Could we be headed for a replay of the mp3’s assault on the album?

The wholeness of the book has to some extent always been illusory, and reading far more fragmentary than we tend to admit. A number of things have clouded our view: the economic imperative to publish whole volumes (it’s more cost-effective to produce good aggregations of content than to publish lots of individual options, or to allow readers to build their own); romantic notions of deep, cover-to-cover reading; and more recently, the guilty conscience of the harried book consumer (when we buy a book we like to think that we’ll read the whole thing, yet our shelves are packed with unfinished adventures).

But think of all the books that you value just for a few particular nuggets, or the books that could have been longish essays but were puffed up and padded to qualify as $24.95 commodities (so many!). Any academic will tell you that it is not only appropriate but vital to a researcher’s survival to hone in on the parts of a book one needs and not waste time on the rest (I’ve received several tutorials from professors and graduate students on the fine art of fileting a monograph). Not all thoughts are book-sized and not all reading goes in a straight line. Selective reading is probably as old as reading itself.

Unbundling the book has the potential to allow various forms of knowledge to find the shapes and sizes that fit them best. And when all the pieces are interconnected in the network, and subject to social discovery tools like tagging, RSS and APIs, readers could begin to assume a role traditionally played by publishers, editors and librarians — the role of piecing things together. Here’s the bit of Peter’s conversation that goes into this:

Peter: …the Google- empowered vision of the “network of books” which is itself partially a romantic, academic notion that might actually be a distinctly net minus for publishers. Potentially great for academics and readers, but potentially deadly for publishers (not to mention librarians). As opposed to the simple first order advantage of having the books discoverable in the first place – but the extent to which books are mined and then inter-connected – that is an interesting and very difficult challenge for publishers.

Am I missing something…?

Friend: If you mean, are book publishers as we know them doomed? Then the answer is “probably yes.” But it isn’t Google’s connecting everything together that’s doing it. If people still want books, all this promotion of discovery will obviously help. But if they want nuggets of information, it won’t. Obviously, a big part of the consumer market that book publishers have owned for 200 years want the nuggets, not a narrative. They’re going, going, gone. The skills of a “publisher” — developing content and connecting it to markets — will have to be applied in different ways.

Peter: I agree that it is not the mechanical act of interconnection that is to blame but the demand side preference for chunks of texts. And the demand is probably extremely high, I agree.

The challenge you describe for publishers – analogous in its own way to that for libraries – is so fundamentally huge as to mystify the mind. In my own library domain, I find it hard to imagine profoundly differently enough to capture a glimpse of this future. We tinker with fabrics and dyes and stitches but have not yet imagined a whole new manner of clothing.

Friend: Well, the aggregation and then parceling out of printed information has evolved since Gutenberg and is now quite sophisticated. Every aspect of how it is organized is pretty much entirely an anachronism. There’s a lot of inertia to preserve current forms: most people aren’t of a frame of mind to start assembling their own reading material and the tools aren’t really there for it anyway.

Peter: They will be there. Arguably, when you look at things like RSS and Yahoo Pipes and things like that – it’s getting closer to what people need.

And really, it is not always about assembling pieces from many different places. I might just want the pieces, not the assemblage. That’s the big difference, it seems to me. That’s what breaks the current picture.

Friend: Yes, but those who DO want an assemblage will be able to create their own. And the other thing I think we’re pointed at, but haven’t arrived at yet, is the ability of any people to simply collect by themselves with whatever they like best in all available media. You like the Civil War? Well, by 2020, you’ll have battle reenactments in virtual reality along with an unlimited number of bios of every character tied to the movies etc. etc. etc. I see a big intellectual change; a balkanization of society along lines of interest. A continuation of the breakdown of the 3-television network (CBS, NBC, ABC) social consensus.