Another grassroots media experiment has sprung up in the hinterlands: YourHub.com, a cluster of community portals in the greater Denver metropolitan area that, like Bluffton Today, invites users to forge their own local news from submitted stories, images, ads and events listings. And like its South Carolina counterpart, YourHub is being launched by a larger media company, The Rocky Mountain News.

(via Dan Gillmor)

Category Archives: the_networked_book

britannica storms wikipedia – networked accumulatio

![]() Beginning on as an april fool’s prank, Britannica’s hostile takeover of Wikipedia has snowballed over the past few days into a sprawling collaborative goof-off on a nerdy conspiracy theory. The article is currently being considered for deletion, or consignment to Wikipedia’s Bad Jokes and Other Deleted Nonsense archive. A funny specimen of web accumulatio (thanks, Infocult).

Beginning on as an april fool’s prank, Britannica’s hostile takeover of Wikipedia has snowballed over the past few days into a sprawling collaborative goof-off on a nerdy conspiracy theory. The article is currently being considered for deletion, or consignment to Wikipedia’s Bad Jokes and Other Deleted Nonsense archive. A funny specimen of web accumulatio (thanks, Infocult).

visions of revisions

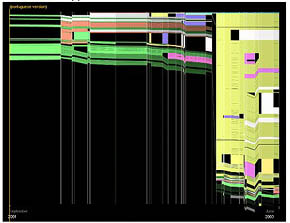

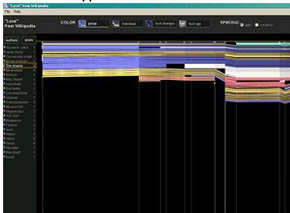

What does the evolution of a complex, multi-authored document look like over time? Below are revision histories of two Wikipedia articles, “Brazil” and “love,” as rendered by History Flow Visualization, a new application from alphaWorks, the emerging technologies division at IBM.

Changes are depicted as parallelograms along two axes, the vertical axis representing the document’s length, and the horizontal axis representing time. The tool offers “community” or single-author views, and uses color to emphasize or isolate specific information – i.e. to distinguish authors, or to measure age of a contribution. (view screenshots)

If you open Wikipedia’s revision history of the Brazil article, you find a daunting list of hundreds of recorded changes. It’s hard to get any sense of how this history compares in overall shape, complexity, and pattern of growth to that of love. But with the alphaWorks tool, it’s clear at a glance that the Brazil article almost tripled in size in 2003, and seems to have been suddenly saturated in yellow (perhaps representing the preponderant influence of a single author?). We’re looking not at a list, but a situation: in 2003, a self-designated authority on Brazil swaggered in and assumed leadership of the country’s wiki-destiny, whereas love seems to have grown at a fairly constant rate with a pretty consistent mix of contributors – no swaggering, yellow Brazilians.

I’d say that the alphaWorks tool suggests something powerful, but is probably of limited use. It’s good at providing the quick glance, but seems a little too mashed and muddled for line-by-line analysis. Good visualization tools are those that give a sense of the whole but also allow for minute investigation. At their best, they convey information meaningfully, even movingly. Nurturing a complex, multi-authored work is in some ways like raising a child. You mark its height against the wall, take photographs, file away old homework assignments, gather artifacts – in short, you construct a history, of “a hundred indecisions..and..a hundred visions and revisions.”

(from Slashdot via reBlog)

the book as community: wikicities

Jimmy Wales, creator of the not-for-profit Wikipedia has launched a for-profit, ad-supported site called Wikicities, which offers users “free MediaWiki hosting for a community to build a free content wiki-based website.”

In yesterday’s Wall Street Journal, Vauhini Vara noted that gaming communities have been particularly enthusiastic. “Laurence Parry, a 22-year-old computer programmer, who co-founded a wiki dedicated to a computer-game series called Creatures and now spends up to several hours a day updating the site. Before the Creatures wiki existed, fans of the game swapped tips in scattered online forums.”

The brilliance of this idea is it just might succeed in centralizing the online gathering place. Internet-based tribal communities that meet to discuss common interests can create their own “city” within the greater universe of Wikicities.com The communal spaces can be defined in the recommended “mission statement.” Wikicities also gives users advice on “developing your community” and “setting boundaries.”

In a recent Wired Magazine article Daniel H. Pink wondered if this is, in fact, a new idea.

It may feel like we’ve been down this road before – remember GeoCities and theglobe.com? But Wales says this is different because those earlier sites lacked any mechanism for true community. “It was just free home-pages,” he says. WikiCities, he believes, will let people who share a passion also share a project. They’ll be able to design and build projects together.

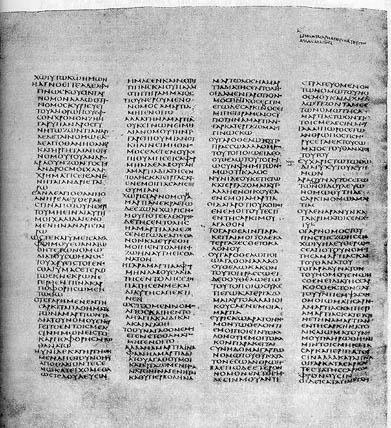

bible fragments reunite in digital space

Plans were recently announced for the digitization of the Codex Sinaiticus, the world’s oldest existing Bible, which currently resides in four separate chunks in Egypt, Russia, Germany and Britain. Dating back to the mid-4th century, the Codex contains large portions in Greek of the Old Testament, and the complete New Testament, including several non-canonical epistles.

From article:

“The project encompasses four strands: conservation, digitisation, transcription and scholarly commentary to make the Codex available for a worldwide audience of all ages and levels of interest. There are plans for a range of projects including a free to view website, a high quality digital facsimile and CD Rom. It is intended that this project will be a model for future collaborations on other manuscripts.”

a book by Lawrence Lessig and you

Lawrence Lessig is inviting everyone to help revise and update his landmark 1999 book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace on a public wiki, as a way of drawing “upon the creativity and knowledge of the community.” (story in Mercury News)

From the site: “This is an online, collaborative book update; a first of its kind. Once the the project nears completion, Professor Lessig will take the contents of this wiki and ready it for publication. The

resulting book, Code v.2, will be published in late 2005 by Basic Books. All royalties, including the book advance, will be donated to Creative Commons.”

As an experiment with networked books, this has a couple of big things going for it. For one, it is a pre-existent work with a large reader community. Like a stone tossed in the water, it creates ripples. Version 2 might benefit by incorporating these ripples. Secondly, Lessig will retain ultimate editorial authority, so we can be pretty sure that the final revision will be focused and well-shaped. And lastly, Lessig’s subject is so vast, so multi-dimensional, that the book will almost certainly benefit from broad reader/writer input. And for someone like Lessig, who is as much an activist as a scholar, constantly running around the world spreading his ideas, it is a nice way of asking for assistance in the time-consuming process of updating of a book that the world needs sooner rather than later.

Incidentally, Lessig will be appearing on April 7 at the New York Public Library with Wilco frontman Jeff Tweedy to discuss the question, “Who Owns Culture?” moderated by Steven Johnson. (thanks, NEWSgrist)

Tweedy says: “A piece of art is not a loaf of bread. When someone steals a loaf of bread from the store, that’s it. The loaf of bread is gone. When someone downloads a piece of music, it’s just data until the listener puts that music back together with their own ears, their mind, their subjective

experience.”

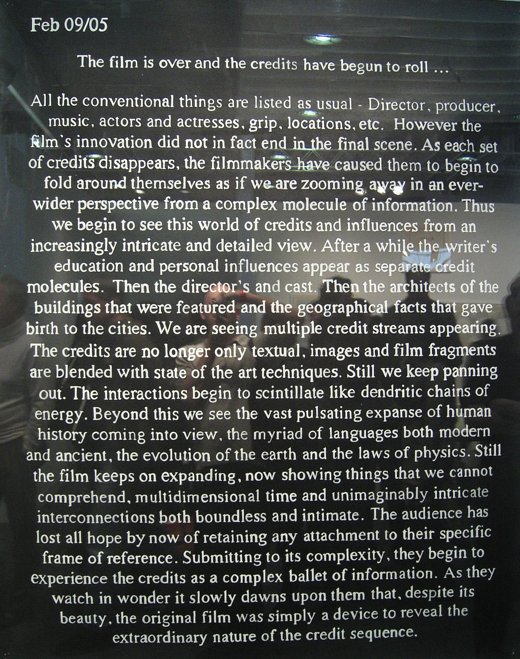

the film is over and the credits have begun to roll

went to the armory show over the weekend. most conceptually interesting piece i saw was a large “poster” which described the credits to a film as an entry point to an ever-expanding chain of related information . . . basically suggesting that all knowledge can be linked in a semantic web to all other knowledge . . . theoretically the internet will develop to the point that this will be actually true instead of just conceptiually true. (emabarrassed to admit that in my excitement i didn’t get the name of the artist; if anyone recognizes the work, please tell us.)

describing humanity in data sets

Yahoo’s recently released commemorative microsite, “Yahoo Netrospective: 10 years, 100 moments,” is a selection of one hundred significant moments in the history of the web (1995-2005). The format for the site was inspired by the work of information architect Jonathan Harris. Harris created 10 x 10, a piece visually identical to, but considerably more interesting than the Yahoo birthday card, (whose content leans quite heavily toward self-promotion, i.e. there are 20 mentions of Yahoo products and no mention at all of Google.) By contrast, Harris’ 10 x 10 builds its fascinating content from RSS feeds. The piece selects the most frequently used words from the major news networks to assemble an hourly “portrait” of our world. “What interests me is trying to find descriptions of humanity in very large data sets, creating programs that tell us something about ourselves,” Harris told Wired News. “We set them free and they come back and tell us what we are like.”

What makes Harris’ work interesting is the self-discipline he exercises in designing these objective systems. By withholding the urge to edit (except, perhaps, when Yahoo is involved) he allows an authentic “picture” of current events, of human behavior online, of the fluid exchange of words and images. His linguistic self-portrait WordCount, harvests data from the British National Corpus. WordCount displays the 86,800 most commonly used words in the English language in order of their commonness. Harris alleges that “observing closely ranked words tells us a great deal about our culture. For instance, “God” is one word from “began”, two words from “start”, and six words from “war”. I tried WordCount and was instantly addicted. To read WordCount or 10 x 10, you have to interact with it and bring meaning to it. Or put another way, you have to be willing to bring meaning to it. This is quite different from the way we experience traditional narratives, whose structure and meaning are crafted by the writer and handed down to the reader. I am eagerly anticipating his next project which, he told Wired, “involves looking at human feelings on a large scale from the web.”

harnessing the collective mind: the ultimate networked book

Dr. Douglas C. Engelbart, who invented the computer mouse and is also credited with pioneering online computing and e-mail, advocates networked books as tools for building what he calls a “dynamic knowledge repository. This would be a place,” Engelbart said, in a recent interview with K. Oanh Ha at Mercury News, “where you can put all different thoughts together that represents the best human understanding of a situation. It would be a well-formed argument. You can see the structure of the argument, people’s assertions on both sides and their proof. This would all be knit together. You could use it for any number of problems. Wikipedia is something similar to it.”

How to conceptualize, organize, build, and use a “book” of that scale, is the project of Engelbart’s Bootstrap Institute. In the “Reasons for Action” section of their website, Engelbart gives his perception of why we need such a book. It reads as follows:

• Our world is a complex place with urgent problems of a global scale.

• The rate, scale, and complex nature of change is unprecedented and beyond the capability of any one person, organization, or even nation to comprehend and respond to.

• Challenges of an exponential scale require an evolutionary coping strategy of a commensurate scale at a cooperative cross-disciplinary, international, cross-cultural level.

• We need a new, co-evolutionary environment capable of handling simultaneous complex social, technical, and economic changes at an appropriate rate and scale.

• The grand challenge is to boost the collective IQ* of organizations and of society. A successful effort brings about an improved capacity for addressing any other grand challenge.

• The improvements gained and applied in their own pursuit will accelerate the improvement of collective IQ. This is a bootstrapping strategy.

• Those organizations, communities, institutions, and nations that successfully bootstrap their collective IQ will achieve the highest levels of performance and success.

“Towards High-Performance Organizations: A Strategic Role for Groupware,” a paper written by Dr. Engelbart in 1992, outlines practical ideas for the architecture of this vast and comprehensive networked book.

All of this is meaty food for thought with regards to our ongoing thread “the networked book.” I am wondering what blog readers think about this? Assuming it becomes possible to collect, map, and analyze the thoughts and opinions of a large community, will it really be to our advantage? Will it necessarily lead to solving the complex problems that Dr. Engelbart speaks of, or will the grand group-think lead to certain dystopian outcomes which may, perhaps, cancel out its IQ-raising value?

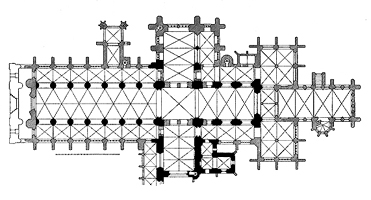

building the cathedral: collaborative authorship and the internet

The World Wide Web is, quite possibly, the most collaborative multi-cultural project in the history of mankind. Millions of people have contributed personal homepages, blogs, and other sites to the growing body of human expression available online. It is, one could say, the secular equivalent of the medieval cathedral, designed by a professional, but constructed by non-professionals, regular folk who are eager to participate in the construction of a legacy. Such is the context for projects like Wikimedia and the Semantic Web, designed by elite programmers, built by the masses.

One of the most pressing questions with regard to collaborative authorship is, can the content be trusted? Does the anonymous group author have the same authority as the credentialed single author? Is our belief in the quality of information inextricably connected to our belief in the authority of the writer? Wikimedia (the non-profit organization that initiated Wikipedia, Wikibooks,, Wiktionary, Wikinews, Wikisource, and Wikiquote) addresses these concerns by offering a new model for collaborative authorship and peer review. Wikipedia’s anonymously published articles undergo peer review via direct peer revision. All revisions are saved and linked; user actions are logged and reversible. “This type of constant editing,” Wikimedia co-director Angela Beesley alleges, “allows you to trust the content over time.” The ambition of Wikimedia is to create a neutral territory where, through open debate, consensus can be reached on even the most contentious topics. The Wikimedia authoring system sets up a democratic forum where contributors construct their own rulespace and policies emerge from consensus-based, rather than top-down, processes. So the authority of the Wikimedia collaborative book depends, in part, on a collective self-discipline that is defined by and enforced by the group.

One of the most pressing questions with regard to collaborative authorship is, can the content be trusted? Does the anonymous group author have the same authority as the credentialed single author? Is our belief in the quality of information inextricably connected to our belief in the authority of the writer? Wikimedia (the non-profit organization that initiated Wikipedia, Wikibooks,, Wiktionary, Wikinews, Wikisource, and Wikiquote) addresses these concerns by offering a new model for collaborative authorship and peer review. Wikipedia’s anonymously published articles undergo peer review via direct peer revision. All revisions are saved and linked; user actions are logged and reversible. “This type of constant editing,” Wikimedia co-director Angela Beesley alleges, “allows you to trust the content over time.” The ambition of Wikimedia is to create a neutral territory where, through open debate, consensus can be reached on even the most contentious topics. The Wikimedia authoring system sets up a democratic forum where contributors construct their own rulespace and policies emerge from consensus-based, rather than top-down, processes. So the authority of the Wikimedia collaborative book depends, in part, on a collective self-discipline that is defined by and enforced by the group.

The collaborative authoring environment engendered by the web will make even more ambitious and far-reaching projects possible. Projects like the Semantic Web, which aims to make all content searchable by allowing users to assign semantic meaning to their work, will organize the prodigious output of collaborative networks, and could, potentially, cast the entire web as a collaboratively authored “book.”