The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

The Encyclopedia Britannica versus Wikipedia saga continues. As Ben has recently posted, Britannica has been confronting Nature on its article which found that the two encyclopedias were fairly equal in the accuracy of their science articles. Today, the editors and the board of directors of Encyclopedia Britannica, have taken out a half page ad in today New York Times (A19) to present an open letter to Nature which requests for a public reaction of the article.

Several interesting things are going on here. Because Britannica chose to place an ad in the Times, it shifted the argument and debate away from the peer review / editorial context into one of rhetoric and public relations. Further, their conscious move to take the argument to the “public” or the “masses” with an open letter is ironic because the New York TImes does not display its print ads online, therefore access of the letter is limited to the Time’s print readership. (Not to mention, the letter is addressed to the Nature Publishing Group located in London. If anyone knows that a similar letter was printed in the UK, please let us know.) Readers here can click on the thumbnail image to read the entire text of the letter. Ben raised an interesting question here today, asking where one might post a similar open letter on the Internet.

Britannica cites many important criticisms of Nature’s article, including: using text not from Britannica, using excerpts out of context, giving equal weight to minor and major errors, and writing a misleading headline. If their accusations are true, then Nature should redo the study. However, to harp upon Nature’s methods is to miss the point. Britannica cannot do anything to stop Wikipedia, except to try to discredit to this study. Disproving Nature’s methodology will have a limited effect on the growth of Wikipedia. People do not mind that Wikipedia is not perfect. The JKF assassination / Seigenthaler episode showed that. Britannica’s efforts will only lead to more studies, which will inevitably will show errors in both encyclopedias. They acknowledge in today’s letter that, “Britannica has never claimed to be error-free.” Therefore, they are undermining their own authority, as people who never thought about the accuracy of Britannica are doing just that now. Perhaps, people will not mind that Britannica contains errors as well. In their determination to show the world that of the two encyclopedias which both content flaws, they are also advertising that of the two, the free one has some-what more errors.

In the end, I agree with Ben’s previous post that the Nature article in question has a marginal relevance to the bigger picture. The main point is that Wikipedia works amazingly well and contains articles that Britannica never will. It is a revolutionary way to collaboratively share knowledge. That we should give consideration to the source of our information we encounter, be it the Encyclopedia Britannica, Wikipedia, Nature or the New York Time, is nothing new.

Category Archives: the_networked_book

the social life of books

One of the most exciting things about Sophie, the open-source software the institute is currently developing, is that it will enable readers and writers to have conversations inside of books — both live chats and asynchronous exchanges through comments and social annotation. I touched on this idea of books as social software in my most recent “The Book is Reading You” post, and we’re exploring it right now through our networked book experiments with authors Mitch Stephens, and soon, McKenzie Wark, both of whom are writing books and opening up the process (with a little help from us) to readers. It’s a big part of our thinking here at the institute.

Catching up with some backlogged blog reading, I came across a little something from David Weinberger that suggests he shares our enthusiasm:

I can’t wait until we’re all reading on e-books. Because they’ll be networked, reading will become social. Book clubs will be continuous, global, ubiquitous, and as diverse as the Web.

And just think of being an author who gets to see which sections readers are underlining and scribbling next to. Just think of being an author given permission to reply.

I can’t wait.

Of course, ebooks as currently envisioned by Google and Amazon, bolted into restrictive IP enclosures, won’t allow for this kind of exchange. That’s why we need to be thinking hard right now about an alternative electronic publishing system. It may seem premature to say this — now, when electronic books are a marginal form — but before we know it, these companies will be the main purveyors of all media, including books, and we’ll wonder what the hell happened.

britannica bites back (do we care?)

![]() Late last year, Nature Magazine let loose a small shockwave when it published results from a study that had compared science articles in Encyclopedia Britannica to corresponding entries in Wikipedia. Both encyclopedias, the study concluded, contain numerous errors, with Britannica holding only a slight edge in accuracy. Shaking, as it did, a great many assumptions of authority, this was generally viewed as a great victory for the five-year-old Wikipedia, vindicating its model of decentralized amateur production.

Late last year, Nature Magazine let loose a small shockwave when it published results from a study that had compared science articles in Encyclopedia Britannica to corresponding entries in Wikipedia. Both encyclopedias, the study concluded, contain numerous errors, with Britannica holding only a slight edge in accuracy. Shaking, as it did, a great many assumptions of authority, this was generally viewed as a great victory for the five-year-old Wikipedia, vindicating its model of decentralized amateur production.

Now comes this: a document (download PDF) just published on the Encyclopedia Britannica website claims that the Nature study was “fatally flawed”:

Almost everything about the journal’s investigation, from the criteria for identifying inaccuracies to the discrepancy between the article text and its headline, was wrong and misleading.

What are we to make of this? And if Britannica’s right, what are we to make of Nature? I can’t help but feel that in the end it doesn’t matter. Jabs and parries will inevitably be exchanged, yet Wikipedia continues to grow and evolve, containing multitudes, full of truth and full of error, ultimately indifferent to the censure or approval of the old guard. It is a fact: Wikipedia now contains over a million articles in english, nearly 223 thousand in Polish, nearly 195 thousand in Japanese and 104 thousand in Spanish; it is broadly consulted, it is free and, at least for now, non-commercial.

At the moment, I feel optimistic that in the long arc of time Wikipedia will bend toward excellence. Others fear that muddled mediocrity can be the only result. Again, I find myself not really caring. Wikipedia is one of those things that makes me hopeful about the future of the web. No matter how accurate or inaccurate it becomes, it is honest. Its messiness is the messiness of life.

googlezon and the publishing industry: a defining moment for books?

Yesterday Roger Sperberg made a thoughtful comment on my latest Google Books post in which he articulated (more precisely than I was able to do) the causes and potential consequences of the publisher’s quest for control. I’m working through these ideas with the thought of possibly writing an article, so I’m reposting my response (with a few additions) here. Would appreciate any feedback…

What’s interesting is how the Google/Amazon move into online books recapitulates the first flurry of ebook speculation in the mid-to-late 90s. At that time, the discussion was all about ebook reading devices, but then as now, the publish industry’s pursuit of legal and techological control of digital books seemed to bring with it a corresponding struggle for control over the definition of digital books — i.e. what is the book going to become in the digital age? The word “ebook” — generally understood as a digital version of a print book — is itself part of this legacy of trying to stablize the definition of books amid massively destablizing change. Of course the problem with this is that it throws up all sorts of walls — literal and conceptual — that close off avenues of innovation and rob books of much of their potential enrichment in the electronic environment.

Clifford Lynch described this well in his important 2001 essay “The Battle to Define to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World”:

Clifford Lynch described this well in his important 2001 essay “The Battle to Define to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World”:

…e-book readers may be the price that the publishing industry imposes, or tries to impose, on consumers, as part of the bargain that will make large numbers of interesting works available in electronic form. As a by-product, they may well constrain the widespread acceptance of the new genres of digital books and the extent to which they will be thought of as part of the canon of respectable digital “printed” works.

A similar bargain is being struck now between publishers and two of the great architects of the internet: Google and Amazon. Naturally, they accept the publishers’ uninspired definition of electronic books — highly restricted digital facsimiles of print books — since it guarantees them the most profit now. But it points in the long run to a malnourished digital culture (and maybe, paradoxically, the persistence of print? since paper books can’t be regulated so devilishly).

As these companies come of age, they behave less and less like the upstart innovators they originally were, and more like the big corporations they’ve become. We see their grand vision (especially Google’s) contract as the focus turns to near-term success and the fluctuations of stock. It creates a weird paradox: Google Book Search totally revolutionizes the way we search and find connections between books, but amounts to a huge setback in the way we read them.

(For those of you interested in reading Lynch’s full essay, there’s a TK3 version that is far more comfortable to read than the basic online text. Click the image above or go here to download. You’ll have to download the free TK3 Reader first, which takes about 10 seconds. Everything can be found at the above link).

the book is reading you, part 3

News broke quietly a little over a week ago that Google will begin selling full digital book editions from participating publishers. This will not, Google makes clear, extend to books from its Library Project — still a bone of contention between Google and the industry groups that have brought suit against it for scanning in-copyright works (75% of which — it boggles the mind — are out of print).

Let’s be clear: when they say book, they mean it in a pretty impoverished sense. Google’s ebooks will not be full digital editions, at least not in the way we would want: with attention paid to design and the reading experience in general. All you’ll get is the right to access the full scanned edition online.

Let’s be clear: when they say book, they mean it in a pretty impoverished sense. Google’s ebooks will not be full digital editions, at least not in the way we would want: with attention paid to design and the reading experience in general. All you’ll get is the right to access the full scanned edition online.

Much like Amazon’s projected Upgrade program, you’re not so much buying a book as a searchable digital companion to the print version. The book will not be downloadable, printable or shareable in any way, save for inviting a friend to sit beside you and read it on your screen. Fine, so it will be useful to have fully searchable texts, but what value is there other than this? And what might this suggest about the future of publishing as envisioned by companies like Google and Amazon, not to mention the future of our right to read?

About a month ago, Cory Doctorow wrote a long essay on Boing Boing exhorting publishers to wake up to the golden opportunities of Book Search. Not only should they not be contesting Google’s fair use claim, he argued, but they should be sending fruit baskets to express their gratitude. Allowing books to dwell in greater numbers on the internet saves them from falling off the digital train of progress and from losing relevance in people’s lives. Doctorow isn’t talking about a bookstore (he wrote this before the ebook announcement), or a full-fledged digital library, but simply a searchable index — something that will make books at least partially functional within the social sphere of the net.

This idea of the social life of books is crucial. To Doctorow it’s quite plain that books — as entertainment, as a diversion, as a place to stick your head for a while — are losing ground in a major way not only to electronic media like movies, TV and video games (that’s been happening for a while), but to new social rituals developing on the net and on portable networked devices.

Though print will always offer inimitable pleasures, the social life of media is moving to the network. That’s why we here at if:book care so much about issues, tangential as they may seem to the future of the book, like network neutrality, copyright and privacy. These issues are of great concern because they make up the environment for the future of reading and writing. We believe that a free, neutral network, a progressive intellectual property system, and robust safeguards for privacy are essential conditions for an enlightened digital age.

We also believe in understanding the essence of the new medium we are in the process of inventing, and about understanding the essential nature of books. The networked book is not a block on a shelf — it is a piece of social software. A web of revisions, interactions, annotations and references. “A piece of intellectual territory.” It can’t be measured in copies. Yet publishers want electronic books to behave like physical objects because physical objects can be controlled. Sales can be recorded, money counted. That’s why the electronic book market hasn’t materialized. Partly because people aren’t quite ready to begin reading books on screens, but also because publishers have been so half-hearted about publishing electronically.

They can’t even begin to imagine how books might be enhanced and expanded in a digital environment, so terrified are they of their entire industry being flushed down the internet drain — with hackers and pirates cannibalizing the literary system. To them, electronic publishing is grit your teeth and wait for the pain. A book is a PDF, some DRM and a prayer. Which is why they’ve reacted so heavy-handedly to Google’s book project. If they lose even a sliver of control, so they are convinced, all hell could break loose.

But wait! Google and Amazon are here to save the day. They understand the internet (naturally — they helped invent it). They understand the social dimension of online spaces. They know how to harness network effects and how to read the embedded desires of readers in the terms and titles for which they search. So they understand the social life of books on the network, right? And surely they will come up with a vision for electronic publishing that is both profitable for the creators and every bit as rich as the print culture that preceded it. Surely the future of the book lies with them?

Sadly, judging by their initial moves into electronic books, we should hope it does not. Understanding the social aspect of the internet also enables you to cunningly restrict it, more cunningly than any print publishers could figure out how to do.

Sadly, judging by their initial moves into electronic books, we should hope it does not. Understanding the social aspect of the internet also enables you to cunningly restrict it, more cunningly than any print publishers could figure out how to do.

Yes, they’ll give you the option of buying a book that lives its life on line, but like a chicken in a poultry plant, packed in a dark crate stuffed with feed tubes, it’s not much of a life. Or better, let’s evaluate it in the terms of a social space — say, a seminar room or book discussion group. In a Google/Amazon ebook you will not be allowed to:

– discuss

– quote

– share

– make notes

– make reference

– build upon

This is the book as antisocial software. Reading is done in solitary confinement, closely monitored by the network overseers. Google and Amazon’s ebooks are essentially, as David Rothman puts it on Teleread, “in a glass case in a museum.” Get too close to the art and motion sensors trigger the alarm.

So ultimately we can’t rely on the big technology companies to make the right decisions for our future. Google’s “fair use” claim for building its books database may be bold and progressive, but its idea of ebooks clearly is not. Even looking solely at the searchable database component of the project, let’s not forget that Google’s ranking system (as Siva Vaidhyanathan has repeatedly reminded us) is non-transparent. In other words, when we do a search on Google Books, we don’t know why the results come up in the order that they do. It’s non-transparent librarianship. Information mystery rather than information science. What secret algorithmic processes are reordering our knowledge and, over time, reordering our minds? And are they immune to commercial interests? And shouldn’t this be of concern to the libraries who have so blithely outsourced the task of digitization? I repeat: Google will make the right choices only when it is in its interest to do so. Its recent actions in China should leave no doubt.

Perhaps someday soon they’ll ease up a bit and let you download a copy, but that would only be because the hardware we are using at that point will be fitted with a “trusted computing” module, which which will monitor what media you use on your machine and how you use it. At that point, copyright will quite literally be the system. Enforcement will be unnecessary since every potential transgression will be preempted through hardwired code. Surveillance will be complete. Control total. Your rights surrendered simply by logging on.

serial killer

Alex Lencicki is a blogger with experience serializing novels online. Today, in a comment to my Slate networked book post, he links to a wonderful diatribe on his site deconstructing the myriad ways in which Slate’s web novel experiment is so bad and so self-defeating — a pretty comprehensive list of dos and don’ts that Slate would do well to heed in the future. In a nutshell, Slate has taken a novel by a popular writer and apparently done everything within its power to make it hard to read and hard to find. Why exactly they did this is hard to figure out.

Summing up, Lencicki puts things nicely in context within the history of serial fiction:

The original 19 th century serials worked because they were optimized for newsprint, 21st century serials should be optimized for the way people use the web. People check blogs daily, they download pages to their phones, they print them out at work and take them downstairs on a smoke break. There’s plenty of room in all that activity to read a serial novel – in fact, that activity is well suited to the mode. But instead of issuing press releases and promising to revolutionize literature, publishers should focus on releasing the books so that people can read them online. It’s easy to get lost in a good book when the book adapts to you.

slate publishes a networked book

Always full of surprises, Slate Magazine has launched an interesting literary experiment: a serial novel by Walter Kirn called (appropriately for a networked book) The Unbinding, to be published twice weekly, exclusively online, through June. From the original announcement:

Always full of surprises, Slate Magazine has launched an interesting literary experiment: a serial novel by Walter Kirn called (appropriately for a networked book) The Unbinding, to be published twice weekly, exclusively online, through June. From the original announcement:

On Monday, March 13, Slate will launch an exciting new publishing venture: an online novel written in real time, by award-winning novelist Walter Kirn. Installments of the novel, titled The Unbinding, will appear in Slate roughly twice a week from March through June. While novels have been serialized in mainstream online publications before, this is the first time a prominent novelist has published a genuine Net Novel–one that takes advantage of, and draws inspiration from, the capacities of the Internet. The Unbinding, a dark comedy set in the near future, is a compilation of “found documents”–online diary entries, e-mails, surveillance reports, etc. It will make use of the Internet’s unique capacity to respond to events as they happen, linking to documents and other Web sites. In other words, The Unbinding is conceived for the Web, rather than adapted to it.

Its publication also marks the debut of Slate’s fiction section. Over the past decade, there has been much discussion of the lack of literature being written on the Web. When Stephen King experimented with the medium in the year 2000, publishing a novel online called The Plant, readers were hampered by dial-up access. But the prevalence of broadband and increasing comfort with online reading makes the publication of a novel like The Unbinding possible.

The Unbinding seems to be straight-up serial fiction, mounted in Flash with downloadable PDFs available. There doesn’t appear to be anything set up for reader feedback. All in all, a rather conservative effort toward a networked book: not a great deal of attention paid to design, not playing much with medium, although the integration of other web genres in its narrative — the “found documents” — could be interesting (House of Leaves?). Still, considering the diminishing space for fiction in mainstream magazines, and the high visibility of this experiment, this is most welcome. The first installment is up: let’s take a look.

google buys writely, or, the book is reading you, part 2

Last week Google bought Upstartle, a small company that created an online word processing program called Writely.  Writely is like a stripped-down Microsoft Word, with the crucial difference that it exists entirely online, allowing you to write, edit, publish and store documents (individually or in collaboration with others) on the network without being tied to any particular machine or copy of a program. This evidently confirms the much speculated-about Google office suite with Writely and Gmail as cornerstone, and presumably has Bill Gates shitting bricks .

Writely is like a stripped-down Microsoft Word, with the crucial difference that it exists entirely online, allowing you to write, edit, publish and store documents (individually or in collaboration with others) on the network without being tied to any particular machine or copy of a program. This evidently confirms the much speculated-about Google office suite with Writely and Gmail as cornerstone, and presumably has Bill Gates shitting bricks .

Back in January, I noted that Google requires you to be logged in with a Google ID to access full page views of copyrighted works in its Book Search service. Which gave me the eerie feeling that the books are reading us: capturing our clickstreams, keywords, zip codes even — and, of course, all the pages we’ve traversed. This isn’t necessarily a new thing. Amazon has been doing it for a while and has built a sophisticated personalized recommendation system out of it — a serendipity engine that makes up for some of the lost pleasures of browsing a physical store. There it seems fairly harmless, useful actually, though it depends on who you ask (my mother says it gives her the willies). Gmail is what has me spooked. The constant sprinkle of contextual ads in the margin attaching like barnacles to my bot-scoured correspondences. Google’s acquisition of Writely suggests that things will only get spookier.

I’ve been a webmail user for the past several years, and more recently a blogger (which is a sort of online word processing) but I’m uneasy about what the Writely-Google union portends — about moving the bulk of my creative output into a surveilled space where the actual content of what I’m working on becomes an asset of the private company that supplies the tools.

Imagine you’re writing your opus and ads, drawn from words and themes in your work, are popping up in the periphery. Or the program senses line breaks resembling verse, and you get solicited for publication — before you’ve even finished writing — in one of those suckers’ poetry anthologies.  Leave the cursor blinking too long on a blank page and it starts advertising cures for writers’ block. Copy from a copyrighted source and Writely orders you to cease and desist after matching your text in a unique character string database. Write an essay about terrorists and child pornographers and you find yourself flagged.

Leave the cursor blinking too long on a blank page and it starts advertising cures for writers’ block. Copy from a copyrighted source and Writely orders you to cease and desist after matching your text in a unique character string database. Write an essay about terrorists and child pornographers and you find yourself flagged.

Reading and writing migrated to the computer, and now the computer — all except the basic hardware — is migrating to the network. We here at the institute talk about this as the dawn of the networked book, and we have open source software in development that will enable the writing of this new sort of born-digital book (online word processing being just part of it). But in many cases, the networked book will live in an increasingly commercial context, tattooed and watermarked (like our clothing) with a dozen bubbly logos and scoured by a million mechanical eyes.

Suddenly, that smarmy little paper clip character always popping up in Microsoft Word doesn’t seem quite so bad. Annoying as he is, at least he has an off switch. And at least he’s not taking your words and throwing them back at you as advertisements — re-writing you, as it were. Forgive me if I sound a bit paranoid — I’m just trying to underscore the privacy issues. Like a frog in a pot of slowly heating water, we don’t really notice until it’s too late that things are rising to a boil. Then again, being highly adaptive creatures, we’ll more likely get accustomed to this softer standard of privacy and learn to withstand the heat — or simply not be bothered at all.

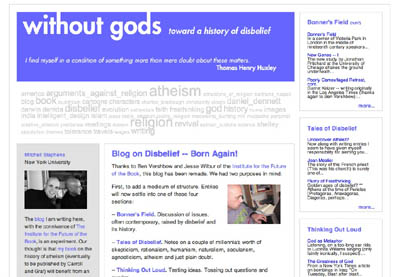

without gods: born again!

Unrest in the Middle East. Cartoons circulated and Danish flags set ablaze (who knew there were so many Danish flags?) A high-profile debate in the pages of the New York Times between a prominent atheist and a Judeo-Christian humanist. Another setback for the “intelligent design” folks, this time in Utah. Things have been busy of late. The world rife with conflict: belief and disbelief, secular pluralism and religious extremism, faith and reason, and all the hazy territory in between.

Mitchell Stephens, too, has been busy, grappling with all the above on Without Gods while trying to muster the opening chapters of his book — the blog serving as both helper and hindrance to his process (a fascinating paradox that haunts the book in the network). To reflect these busy times — and Mitch’s busy mind — the blog has undergone slight renovation, reflecting the busier layout of a newspaper while hopefully remaining accessible and easy to read.

There’s a tag cloud near the top serving as a sort of snapshot of Mitch’s themes and characters, while four topic areas to the side give the reader more options for navigating the site. In some ways the new design also reminds me of the clutter of a writer’s desk — a method-infused madness.

As templates were updated and wrinkles ironed out in the code, Mitch posted a few reflections on the pluses and pitfalls of this infant form, the blog:

Newspapers, too, began, in the 17th century, by simply placing short items in columns (in this case from top down). So it was possible to read on page four of a newspaper in England in 1655 that Cardinal Carassa is one of six men with a chance to become the next pope and then read on page nine of the same paper that Carassa “is newly dead.” Won’t we soon be getting similar chuckles out of these early blogs — where leads are routinely buried under supporting paragraphs; where whim is privileged, coherence discouraged; where the newly dead may be resurrected as one scrolls down.

Early newspapers eventually discovered the joys of what journalism’s first editor called a “continued relation.” Later they discovered layout.

Blogs have a lot of discovering ahead of them.

RDF = bigger piles

Last week at a meeting of all the Mellon funded projects I heard a lot of discussion about RDF as a key technology for interoperability. RDF (Resource Description Framework) is a data model for machine readable metadata and a necessary, but not sufficient requirement for the semantic web. On top of this data model you need applications that can read RDF. On top of the applications you need the ability to understand the meaning in the RDF structured data. This is the really hard part: matching the meaning of two pieces of data from two different contexts still requires human judgement. There are people working on the complex algorithmic gymnastics to make this easier, but so far, it’s still in the realm of the experimental.

So why pursue RDF? The goal is to make human knowledge, implicit and explicit, machine readable. Not only machine readable, but automatically shareable and reusable by applications that understand RDF. Researchers pursuing the semantic web hope that by precipitating an integrated and interoperable data environment, application developers will be able to innovate in their business logic and provide better services across a range of data sets.

Why is this so hard? Well, partly because the world is so complex, and although RDF is theoretically able to model an entire world’s worth of data relationships, doing it seamlessly is just plain hard. You can spend time developing a RDF representation of all the data in your world, then someone else will come along with their own world, with their own set of data relationships. Being naturally friendly, you take in their data and realize that they have a completely different view of the category “Author,” “Creator,” “Keywords,” etc. Now you have a big, beautiful dataset, with a thousand similar, but not equivalent pieces. The hard part—determining relationships between the data.

We immediately considered how RDF and Sophie would work. RDF importing/exporting in Sophie could provide value by preparing Sophie for integration with other RDF capable applications. But, as always, the real work is figuring out what it is that people could do with this data. Helping users derive meaning from a dataset begs the question: what kind of meaning are we trying to help them discover? A universe of linguistic analysis? Literary theory? Historical accuracy? I think a dataset that enabled all of these would be 90% metadata, and 10% data. This raises another huge issue: entering semantic metadata requires skill and time, and is therefore relatively rare.

In the end, RDF creates bigger, better piles of data—intact with provenance and other unique characteristics derived from the originating context. This metadata is important information that we’d rather hold on to than irrevocably discard, but it leaves us stuck with a labyrinth of data, until we create the tools to guide us out. RDF is ten years old, yet it hasn’t achieved the acceptance of other solutions, like XML Schemas or DTD’s. They have succeeded because they solve limited problems in restricted ways and require relatively simple effort to implement. RDF’s promise is that it will solve much larger problems with solutions that have more richness and complexity; but ultimately the act of determining meaning or negotiating interoperability between two systems is still a human function. The undeniable fact of it remains— it’s easy to put everyone’s data into RDF, but that just leaves the hard part for last.