Grand Text Auto reports a call for proposals for essays to be included in a reader on machinima. Most often, machinima is the repurposing of video gameplay that is recorded and then re-edited, with additional sound and voice over.

People have been creating machinima with 3D video games, such as Quake, since the late 1990s. Even before that, in the late 80s, my friends and I would record our Nintendo victories on VHS, more in the spirit of DIY skate videos. However, in the last few years, the machinima community has seen tremendous growth, which coincided with the penetration of video editing equipment in the home. What started as ironic short movies have started to grow into fairly elaborate projects.

Until the last few years, social research on games in general was limited and sporadic. In the 1970s and 1980s, the University of Pennsylvania was the rare institution that supported a community of scholars to investigate games and play. A vast proliferation of book and social research exists on gaming and especially video games, which we have discussed here.

Although I love machinima, I am surprised as to how quickly a reader is being produced. Machinima is still a rather fringe phenomena, albeit growing. My first reaction is that machinima is not exactly ready for an entire reader on the subject. I look forward to being surprised by the final selection of essays.

Part of this reaction comes from the notion that machinima is a rather limited form. In my mind, machinima is the repurposing of video game output. However, machinima.org emphasizes capturing live action/ real time digital animation as an essential part of the form, thereby removing the necessity of the video game. Most machinima is created within the virtual video gaming environment because that is where people are able to most readily control and capture 3D animation in real time. Live action or real time capture is different from traditional 3D animation tools (for instance Maya) where you program (and hence control) the motion of your object, background, and camera before you render (or record) the animation rather than during as in machinima.

Broadening of the definition of machinima, as with any form, plays a role on the sustainability of the form. For example, in looking at painting versus sculpture, painting seems to confine what is considered “painting” to pigment on a 2D surface. Where more expansive interpretations of the form get new labeling such as mixed media or multimedia. On the other hand, sculpture has expanded beyond traditional materials of wood, metal, and stone. Thus, the art of James Turrell, who works with landscape, light and interior space can be called sculpture. I do not imply that painting is by any means dead. The 2004 Whitney Biennal had a surprisingly rich display of painting and drawing, as well as photography. However, note the distinction that photography is not considered painting, although photography is 2D medium.

The word machinima comes from combining machine cineama or machine animation. This foundation does pose limits to how far beyond repurposing video game output machinima can go. It is not convincing to try to include the repurposing of traditional film and animation under the label of machinima. Clearly, repurposing material such as japanese movies or cartoons as in Woody Allen’s “What’s Up, Tigerlily?” and the Cartoon Network’s “Sealab 2021” is not machinima. Further more, I am hesitant to call the repurposing of a digital animation machinima. I am not familiar with any examples, but I would not be surprised if they exist.

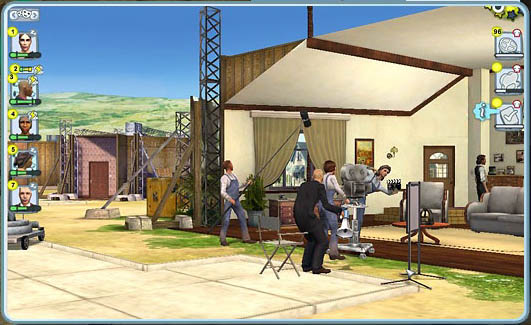

With the release of The Movies, people can use the game’s 3D modeling engine to create wholly new movies. It is not readily clear to me, if The Movies allows for real time control of it’s characters. If it does, then “French Democracy” (the movie made by French teenagers about the Parisian riots in late 2005) should be considered machinima. However, if it does not, then I cannot differentiate the “French Democracy” from films made in Maya or Pixar in-house applications. Clearly, Pixar’s “Toy Story” is not machinima.

As digital forms emerge, the boundaries of our mental constructions guide our understanding and discourse surrounding these forms. I’m realizing that how we define these constructions control not only the relevance but also the sustainability of these forms. Machinima defined solely as repurposed video game output is limiting, and utlimately less interesting than the potential of capturing real time 3D modeling engines as a form of expression, whatever we end up calling it.

Category Archives: the_movies

machinima’s new wave

“The French Democracy” (also here) is a short film about the Paris riots made entirely inside of a computer game. The game, developed by Peter Molyneux‘s Lionhead Productions and called simply “The Movies,” throws players into the shark pool of Hollywood where they get to manage a studio, tangle with investors, hire and fire actors, and of course, produce and distribute movies. The interesting thing is that the movie-making element has taken on a life of its own as films produced inside the game have circulated through the web as free-standing works, generating their own little communities and fan bases.

This is a fascinating development in the brief history of Machinima, or “machine cinema,” a genre of films created inside the engines of popular video game like Halo and The Sims. Basically, you record your game play through a video out feed, edit the footage, and add music and voiceovers, ending up with a totally independent film, often in funny or surreal opposition to the nature of the original game. Bob, for instance, appeared in a Machinima talk show called This Spartan Life, where they talk about art, design and philosophy in the bizarre, apocalyptic landscapes of the Halo game series.

The difference here is that while Machinima is typically made by “hacking” the game engine, “The Movies” provides a dedicated tool kit for making video game-derived films. At the moment, it’s fairly primitive, and “The French Democracy” is not as smooth as other Machinima films that have painstakingly fitted voice and sound to create a seamless riff on the game world. The filmmaker is trying to do a lot with a very restricted set of motifs, unable to add his/her own soundtrack and voices, and having only the basic menu of locales, characters, and audio. The final product can feel rather disjointed, a grab bag of film clichés unevenly stitched together into a story. The dialogue comes only in subtitles that move a little too rapidly, Paris looks suspiciously like Manhattan, and the suburbs, with their split-level houses, are unmistakably American.

But the creative effort here is still quite astonishing. You feel you are seeing something in embryo that will eventually come into its own as a full-fledged art form. Already, “The Movies” online community is developing plug-ins for new props, characters, environments and sound. We can assume that the suite of tools, in this game and elsewhere, will only continue to improve until budding auteurs really do have a full virtual film studio at their disposal.

It’s important to note that, according to the game’s end-user license agreement, all movies made in “The Movies” are effectively owned by Activision, the game’s publisher. Filmmakers, then, can aspire to nothing more than pro-bono promotional work for the parent game. So for a truly independent form to emerge, there needs to be some sort of open-source machinima studio where raw game world material is submitted by a community for the express purpose of remixing. You get all the fantastic puppetry of the genre but with no strings attached.