I’ve always been fascinated by medical illustration. My undergraduate degree was in studio art–figurative sculpture and painting–so I marveled at the technical skill required to make the drawings themselves. But I also appreciated the text. In order to sculpt the human figure, I needed to know precisely what was happening under the skin. I memorized all the muscles and how they moved, every bone in the skeletal system and where it stuck out. I absorbed books like “Gray’s Anatomy,” and Frank Netter’s “Atlas of Human Anatomy.” I thought of them as illuminated manuscripts. The text alone would have been less than useful to me and the illustration without the text would not been enough either. I thought it would be interesting to look at some of these illuminations, think about the intermingling of text and image, and examine their “born digital” equivalents.

Below are two Persian illuminations that I find particularly compelling. The first details the human muscle system. I like its primative feel, the squatting pose and the way the notations look like tribal tattoo, ritual scarification patterns, or the sinews of the muscle itself. The second drawing has the opposite effect, an exaggerated gentility, the patient sits, fully conscious, politely allowing the surgeon to slice open his cranium. Captions for the drawings were taken from an article entitled, “Arab Roots of European Medicine” by David W. Tschanz, MSPH, PhD.

The Anatomy of the Human Body. Persian notations detail the human muscle system in Mansur ibn Ilyas’s late-14th century Tashrih-I Badan-I Insan.

An illustration in The Surgeon’s Tract, an Ottoman text written by Sharaf al-Din in about 1465, indicates where on the scalp incisions should be made.

![]()

Above left: A Dead or Moribund Man in Bust Length; a Detail of the Jaw and Neck; the Muscular and Vascular Systems of the Shoulder and Arm (recto). Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452-Cloux, 1519).

Above right: Detail Section of the Mouth and Throat; the Muscular System of the Shoulder and Arm (verso). Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452-Cloux, 1519).

Renaissance European artist Leonardo da Vinci, created sublime illuminations, heavily annotated with notations made during dissections. The effect of the notations reminds us that these drawings were “studies” of the human body and its mysteries. For me, these drawings are as compelling as Da Vinci’s more “finished” works. When I was seven months pregnant, I waited in line for four hourse to see the Met exhibition: Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman which included the drawings above. It was worth it.

I should also mention one of his contemporaries, Andreas Vesalius, (1514-1564) who was the author of an extremely influential atlas of anatomy.

The modern-day equivalent of Vesalius, might be Frank H. Netter, M.D., whose brillantly illustrated “Atlas of Human Anatomy,” is required reading for many first-year medical students.

Flix Productions’3D animation of the beating heart (click on image) could be considered a born digital update on Netter’s style of medical illustration. No text on this one (so it doesn’t really belong here) but I wanted to indicate how 2D drawings are being “improved” by digital technolgy. This animation gives a 360 view of the heart and shows it in motion. I imagine the text might be read by a narrator or included on the screen on in a pop-out window.

![]()

We can’t overlook, “Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body,” I found this (above left) image in the Bartleby.com edition which is available online. The drawing also seems to be a rather eerie premonition of the sonogram (above right). I like to think of sonograms as machine-generated born digital illuminations. I’ve cropped the text off the one above to protect privacy, but it would normally have useful information about the mother and fetus printed in the margins.

Another iteration of the born digital illumination, this 3D animation of a normal birth created by Nucleus Medical Art. It looks so painless in the movies.

Category Archives: the_form_of_the_book

Information Esthetics lecture series

Brad Paley, creator of Text Arc and many other gorgeous data visualizations popular here at if:book, has put together a fascinating lecture series running March through July in New York. The series starts next Thursday in Chelsea with renowned typographer Robert Bringhurst. From Brad:

“I’m excited to have put together something that seems tailor-made for the interests of Institute for the Future of the Book participants and on-lookers.”

Information Esthetics: Lecture Series One starts March 31 in Chelsea

People who value clarity and engagement is visual displays, whether as fine art or on Wall Street, are invited to seven evenings with some of the field’s deepest thinkers and finest practitioners. The series opens with distinguished typographer Robert Bringhurst at 6:00 pm, March 31 at the Chelsea Art Museum. Fine spirits and snacks will be served. It’s free with the $3 discounted museum admission.

A little more about Information Esthetics..

Making data meaningful–this phrase could describe what dozens of professions strive for: Wall Street systems designers, fine artists, advertising creatives, computer interface researchers, and many others. Occasionally something important happens in these practices: a data representation is created that reveals the subject’s nature with such clarity and grace that it both informs and moves the viewer. We both understand and care. This is the focus of Information Esthetics.

Information Esthetics, a recently formed not-for-profit organization, has organized a lecture series dedicated to helping this happen more often.

For the full program, visit InformationEsthetics.org. Thanks, Brad! We’ll definitely be there.

graphic novel as illuminated manuscript

The institute is hosting a competition called Born Digital 1: Illumination, which asks artists, writers, programmers, and designers to address the conceptual underpinnings of illuminated manuscripts in the context of the born digital artifact. We are playing somewhat loose with the term “illuminated manuscript.” Our “Born Digital” contest asks for a single page rather than an entire book and is not necessarily interested in a literal reinvention of the form (unless you’ve come up with a particularly great one). We are intrigued by the fact that illuminated manuscripts do not separate text and image into different disciplines requiring separate platforms for display and critical discourse. We find that, in the workshop of the digital medium, disciplinary amalgams are once again emerging, and we would like to examine this shift.

Without attempting to give a history of the evolution of this form, I will, over the next several days, point out a few contemporary models that pay tribute to medieval illumination. The graphic novel comes immediately to mind. Chris Ware’s, “Jimmy Corrigan the Smartest Kid on Earth, Art Spiegelman’s, “Maus,” and David B’s, “This Sweet Sickness,” have shown us the power of image and text working in tandem to deliver a profound aesthetic, emotional, and intellectual experience.

Early digital versions of the graphic novel include Pyramids of Mars, which was published in 1997 by Richard Douglas and Geoffrey Holmes, and claims to be the first downloadable digital graphic novel. And Scott Frazier’s TRANSCENDENCE which the author describes as: partially animated, partially illustrated and partially text. It will, hopefully, stretch the bounds of multimedia and become something new, more than a mere fusion of comic and animation.

![]() And thanks to friend Douglas Wolk, the absolute authority on graphic novels (and one of the smartest and nicest guys I know) for the following recommendations: “Patrick Farley’s, “The Spiders,” is wonderful and uses the medium nicely. Dylan Meconis’s, “Bite Me” is pretty much just scanned images, but she serialized the whole thing online, and she’s like 19 years old and super-fun.”

And thanks to friend Douglas Wolk, the absolute authority on graphic novels (and one of the smartest and nicest guys I know) for the following recommendations: “Patrick Farley’s, “The Spiders,” is wonderful and uses the medium nicely. Dylan Meconis’s, “Bite Me” is pretty much just scanned images, but she serialized the whole thing online, and she’s like 19 years old and super-fun.”

I hope this serves as a useful beginning for discussion on graphic novel as illuminated manuscript. I’m relying on readers to help me flesh the idea out.

the gates: an experiment in collective memory

So . . . .about two weeks ago I had a dream, (actually more of a nightmare) in which I was asked to judge a contest to choose “the best photograph of the Gates” from among three million orange photos. Over the next few days, however, the more I thought about it,I became intrigued by the idea of seeing people’s different creative solutions to photographing the gates.

[Note: I loved the Gates. Ashton (partner-in-crime) and I were in the park almost every day we were in the city, we even gave a party for 150 friends who came from all over the world to walk through the park at dawn (see nifty video by alex itin, orange you glad).

On the last day Ashton and I walked through the park for seven straight hours with Rebeca Mendez and Adam Euwens — talking almost the whole time about the phenomenon of the Gates — as an art work that requires significant effort on the part of its audience; like all of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work, it requires you to be at a certain latitude and longitude at a specific moment in time; you need to see it from different vantage points at different times of the day; as Ashton said, “there are as many views of the Gates as footsteps in the park.”

And of course you talk endlessly to the people you meet along the way.

Early that last day, high up on the Harlem Meer, we came upon a big man with red orange hair who was quickly slipping a big coat over his obviously naked body. His friend had just as obviously been taking pictures. Ashton and Rebeca immediately realized that they were taking pictures of his orange pubic hair against the backdrop of the Gates. Impulsively I mentioned that I was planning to sponsor a contest for the best amateur photograph of the Gates. Surprisingly they wrote down a URL for the competition I made up on the spot. A few other times during the day I mentioned this to people who seemed to be taking interesting photos. Without any prompting, they also wrote down the URL.

So the next day, Monday, while sitting around the table with Kim, Dan, and Ben, my colleagues at the Institute for the Future of the Book, I mentioned the whole Gates photo idea and to my delight everyone thought it would fit in perfectly with our experiments in the area of open-ended networked “books.”

Voila — the beginning of the Gates Memory Project which we are launching today at gatesmemory.org. It’s quite a bit more ambitious than the original (and impossible) idea of choosing “the best photo.” Now we are aiming to to harness the creativity and insight of thousands to build a kind of collective memory machine — one that is designed not just for the moment, but as a  lasting and definitive document of the Gates and our experience of them. As Ben Vershbow says in the press release announcing the project, “The photographs are a jumping off point for further exploration. Ultimately, we are interested in collecting anything that can be shared over the web – film, audio, text – parodies and remixes.”

lasting and definitive document of the Gates and our experience of them. As Ben Vershbow says in the press release announcing the project, “The photographs are a jumping off point for further exploration. Ultimately, we are interested in collecting anything that can be shared over the web – film, audio, text – parodies and remixes.”

While the photos and stories are being collected, the institute will encourage discussion and debate on how best to present the archives in hopes of finding new, unexpected ways to view and bring meaning to the content. The institute also welcomes the possibility of collaboration with designers, developers and web curators. This project is the beginning of a long-term exploration for us. Through this work, we are asking: how do we use social software to create works that are in the spirit of the web – i.e. free-form, ad hoc, always evolving, and driven by people’s enthusiasm to share – but are also edited and shaped into something of lasting value? It is that tension – between frozen and fluid works – that we aim to explore. We are excited to see the ideas people will bring to the table.

See the complete call for the project HERE.

describing humanity in data sets

Yahoo’s recently released commemorative microsite, “Yahoo Netrospective: 10 years, 100 moments,” is a selection of one hundred significant moments in the history of the web (1995-2005). The format for the site was inspired by the work of information architect Jonathan Harris. Harris created 10 x 10, a piece visually identical to, but considerably more interesting than the Yahoo birthday card, (whose content leans quite heavily toward self-promotion, i.e. there are 20 mentions of Yahoo products and no mention at all of Google.) By contrast, Harris’ 10 x 10 builds its fascinating content from RSS feeds. The piece selects the most frequently used words from the major news networks to assemble an hourly “portrait” of our world. “What interests me is trying to find descriptions of humanity in very large data sets, creating programs that tell us something about ourselves,” Harris told Wired News. “We set them free and they come back and tell us what we are like.”

What makes Harris’ work interesting is the self-discipline he exercises in designing these objective systems. By withholding the urge to edit (except, perhaps, when Yahoo is involved) he allows an authentic “picture” of current events, of human behavior online, of the fluid exchange of words and images. His linguistic self-portrait WordCount, harvests data from the British National Corpus. WordCount displays the 86,800 most commonly used words in the English language in order of their commonness. Harris alleges that “observing closely ranked words tells us a great deal about our culture. For instance, “God” is one word from “began”, two words from “start”, and six words from “war”. I tried WordCount and was instantly addicted. To read WordCount or 10 x 10, you have to interact with it and bring meaning to it. Or put another way, you have to be willing to bring meaning to it. This is quite different from the way we experience traditional narratives, whose structure and meaning are crafted by the writer and handed down to the reader. I am eagerly anticipating his next project which, he told Wired, “involves looking at human feelings on a large scale from the web.”

harnessing the collective mind: the ultimate networked book

Dr. Douglas C. Engelbart, who invented the computer mouse and is also credited with pioneering online computing and e-mail, advocates networked books as tools for building what he calls a “dynamic knowledge repository. This would be a place,” Engelbart said, in a recent interview with K. Oanh Ha at Mercury News, “where you can put all different thoughts together that represents the best human understanding of a situation. It would be a well-formed argument. You can see the structure of the argument, people’s assertions on both sides and their proof. This would all be knit together. You could use it for any number of problems. Wikipedia is something similar to it.”

How to conceptualize, organize, build, and use a “book” of that scale, is the project of Engelbart’s Bootstrap Institute. In the “Reasons for Action” section of their website, Engelbart gives his perception of why we need such a book. It reads as follows:

• Our world is a complex place with urgent problems of a global scale.

• The rate, scale, and complex nature of change is unprecedented and beyond the capability of any one person, organization, or even nation to comprehend and respond to.

• Challenges of an exponential scale require an evolutionary coping strategy of a commensurate scale at a cooperative cross-disciplinary, international, cross-cultural level.

• We need a new, co-evolutionary environment capable of handling simultaneous complex social, technical, and economic changes at an appropriate rate and scale.

• The grand challenge is to boost the collective IQ* of organizations and of society. A successful effort brings about an improved capacity for addressing any other grand challenge.

• The improvements gained and applied in their own pursuit will accelerate the improvement of collective IQ. This is a bootstrapping strategy.

• Those organizations, communities, institutions, and nations that successfully bootstrap their collective IQ will achieve the highest levels of performance and success.

“Towards High-Performance Organizations: A Strategic Role for Groupware,” a paper written by Dr. Engelbart in 1992, outlines practical ideas for the architecture of this vast and comprehensive networked book.

All of this is meaty food for thought with regards to our ongoing thread “the networked book.” I am wondering what blog readers think about this? Assuming it becomes possible to collect, map, and analyze the thoughts and opinions of a large community, will it really be to our advantage? Will it necessarily lead to solving the complex problems that Dr. Engelbart speaks of, or will the grand group-think lead to certain dystopian outcomes which may, perhaps, cancel out its IQ-raising value?

paperback ebook

Booktopia, a Korean ebook developer, is introducing a 29-title series for mobile users based on popular movie scenarios (article), including the recent Cannes hit Old Boy (thanks, textually.org). The books act as supplements to the films, with omitted material and glimpses behind-the-scenes, sort of like special features on a DVD (though it appears that they will be text-only). They also seem to riff on that weird tie-in genre of books adapted from the screen (I’ve always wondered who reads those books..).

Booktopia, a Korean ebook developer, is introducing a 29-title series for mobile users based on popular movie scenarios (article), including the recent Cannes hit Old Boy (thanks, textually.org). The books act as supplements to the films, with omitted material and glimpses behind-the-scenes, sort of like special features on a DVD (though it appears that they will be text-only). They also seem to riff on that weird tie-in genre of books adapted from the screen (I’ve always wondered who reads those books..).

So are phones the electronic book in embryo? If you are looking for innovation in form, what’s happening on cell phones and mobile devices is far more interesting than what you’ll find in the area of conventional “ebooks,” which generally are the kind of pdf nightmare Dan decribes in his post yesterday. But so far, these kinds of mobile books, or mbooks, are to literature what ring tones are to music. The cell phone has become a kind of cud for the distracted brain to chew – I can’t count how many people I see on the subway or waiting in lines simply fiddling with their phone settings. What seems to be developing on cell phones is a new kind of ephemera descended from the pamphlet, flyer, or broadsheet, which will be tightly interwoven with advertising (these Korean movie tie-ins do leg work for the actual films, just as the new 24 spinoff offered on Verizon plugs the Fox television series). But what about actual books? Serious reading to counterbalance all the fluff. Portable devices like phones and palm pilots lend themselves to the serial model. Their diminutive size makes them better suited to smaller chunks of material, and their access to networks allows them to constantly grab new chunks. But I don’t see why quality has to be sacrificed. Perhaps, with time, the tradition of serialized narrative will be reinvented in meaningful ways. Many of Dickens’s novels were published and written serially, and he was able to modulate the course of his writing according to reader response and sales. Digital content delivery over cell phones and the web could employ the same fluidity, delivering the book as it is becoming, and creating whole communities of readers on the web (see earlier post elegant map hack). An interesting prospect for writers as well as readers.

These literary experiments on the tiny screen are probably not trivial, even though the content may be. They seem to be saying “hurry up” to our more sophisticated but unwieldy reading devices like laptops and tablets. We need a kind of paperback ebook, in between a laptop and a smartphone – cheap and easy to tote. If I can comfortably read on this device in a crowded subway, then we might finally have something as handy as a paper book, conducive to any kind of content, with all the affordances of computers and the web. And ideally… I can write on it with a stylus, or on a keyboard that it projects on a tabletop, and I can dock it at a more powerful workstation in my office. I can plug in headphones or speakers and explore my music library, or surf satellite radio. I can watch a film that I made, or one that I downloaded, or I can flip through my photo album. If I’m lost, I can get a map with pictures of the place I’m trying to find. And at night, I can curl up with it in bed, reading by the light of its built-in candle. I may even have glasses I can plug in and read the book without hands, or look at images in 3-D like on a stereopticon. (Kim, I think I may have my fantasy ebook) Nothing could ever truly replace paper books for me, but a pan-media tablet – an everything device – might just become my everyday companion.

the form of the (electronic) book

Boing Boing points out that professor/prankster Kembrew McLeod has released an electronic version of his new book on copyright Freedom of Expression on his website. The electronic version is released with a Creative Commons license. McLeod’s book has not a little to do with what we’re working on at the Institute, so I quite happily downloaded the book – you can too! – and found myself with a 384-page PDF of the book. It’s indeed the whole book, almost exactly as Doubleday printed it, with the addition of a Creative Commons link on the first page. If you happen to know a book printer and some extra cash, you could send them this file and get a book back in a couple weeks. If you don’t have access to a print shop and extra cash but you do have 384 sheets of 8.5” x 11” paper & a fast laser printer, you could print it out yourself and have your own telephone-book sized stack of Freedom of Expression.

Boing Boing points out that professor/prankster Kembrew McLeod has released an electronic version of his new book on copyright Freedom of Expression on his website. The electronic version is released with a Creative Commons license. McLeod’s book has not a little to do with what we’re working on at the Institute, so I quite happily downloaded the book – you can too! – and found myself with a 384-page PDF of the book. It’s indeed the whole book, almost exactly as Doubleday printed it, with the addition of a Creative Commons link on the first page. If you happen to know a book printer and some extra cash, you could send them this file and get a book back in a couple weeks. If you don’t have access to a print shop and extra cash but you do have 384 sheets of 8.5” x 11” paper & a fast laser printer, you could print it out yourself and have your own telephone-book sized stack of Freedom of Expression.

Of course you could fire up your PDF viewer and read it on the screen of your computer, which is probably what you were expecting to do. But that’s where the trouble starts.

While it’s certainly poor form to complain about what’s being given away for free, it’s a remarkably painful experience to try and read this book on your computer. In large part, this is because it’s not meant to be read on a screen. This PDF is the same file that Doubleday’s production staff sent to the printer – with crop marks and the QuarkXPress filename at the top of every page. Because there’s padding around the text so that it can be safely printed, you need to blow up the magnification to actually be able to read the text. There’s a great deal of wasted space you need to page through (click on the thumbnail at right for an example of how this looked in full-screen Adobe Acrobat on my computer). Because Doubleday’s making books in Quark with no thought to reusing or repurposing content, this file doesn’t have any of the niceties that a PDF could have – an interactive table of contents, for example, is useful in a three-hundred page book. Worse: while one of the great benefits of the Creative Commons license is that it allows users to quote and create derivative works from licensed material. It’s not as simple as you’d like to copy text out of a PDF.

While it’s certainly poor form to complain about what’s being given away for free, it’s a remarkably painful experience to try and read this book on your computer. In large part, this is because it’s not meant to be read on a screen. This PDF is the same file that Doubleday’s production staff sent to the printer – with crop marks and the QuarkXPress filename at the top of every page. Because there’s padding around the text so that it can be safely printed, you need to blow up the magnification to actually be able to read the text. There’s a great deal of wasted space you need to page through (click on the thumbnail at right for an example of how this looked in full-screen Adobe Acrobat on my computer). Because Doubleday’s making books in Quark with no thought to reusing or repurposing content, this file doesn’t have any of the niceties that a PDF could have – an interactive table of contents, for example, is useful in a three-hundred page book. Worse: while one of the great benefits of the Creative Commons license is that it allows users to quote and create derivative works from licensed material. It’s not as simple as you’d like to copy text out of a PDF.

From a design perspective, this is a disaster, and one for which I’ll blame the publishing company – this has absolutely nothing to do with the content of the book, merely the form. While it’s a decent-looking book in print, the printed page doesn’t work in the same way as the screen, and there’s been no accounting for this at all. We take for granted the physical book as an object, although it really is a quietly brilliant design, a perfect synthesis of form and function. When electronic books are presented to the public devoid of both, it’s little wonder they haven’t taken off. Nobody’s going to want to read a book on a screen unless it looks good on the screen. One might be forgiven for imagining that this is a publisher’s scheme to encourage people to buy the actual book.

big plans for the tiny screen

Late last week, Random House announced it was making the microlit plunge, acquiring a “significant minority stake” in wireless applications developer VOCEL (AP wire story).

Says Random House Ventures president Richard Sarnoff: “You have a whole generation of consumers, perhaps more than a generation, who are never more than 10 feet from their cell phones, including when they shower. Increasingly, cell phones are becoming an appliance for entertainment and education.”

But, despite the success of cell phone novels and serials in Japan, South Korea and Germany, Sarnoff insists that tiny screens have a potential for information, but not for narrative. “The screens are inappropriate for that kind of sustained reading. That’s a `maybe, someday’ discussion. We’ll keep an eye on that area, and if something happens … we’ll certainly respond.”

So for the time being, Random House will be testing mobile phones for language instruction, test prep, and other informational services.

In a related vein, textually.org, an invaluable resource for the microlit observer, recently posted about Radio Shack‘s plans to sell stand-alone virtual keyboard units the size of a “small fist.” Virtual keyboards project a regular-sized typing area on a flat surface, registering keystrokes via Bluetooth onto a smartphone or personal digital assistant (PDA). VKB, the developer of the technology, recently announced its goal of making the virtual keyboard an embedded feature in mobile devices by next year. Further suggestion that cell phones and laptops are evolving into one another.

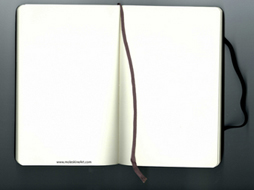

moleskinerie – the steadfast fetish

Last month, I had the good fortune to speak briefly with Peter Lunenfeld at the Scholarship in the Digital Age conference at USC. I was surprised to learn that this famous digital media theorist is currently obsessed with a print-based initiative. His new Mediaworks Pamphlets are “theoretical fetish objects for the 21st century” – elegantly produced collaborations between designer and writer, intended to break serious media theory out of “the hermetically sealed spheres of academia and the techno-culture” and into the public discourse, much like the famous collaboration between Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, “The Medium is the Massage.” By shifting reading, writing and design practices to the screen, Lunenfeld argues, digital media have effectively “taken the weight off” of the print codex, enabling its tactile qualities to flower anew.

Last month, I had the good fortune to speak briefly with Peter Lunenfeld at the Scholarship in the Digital Age conference at USC. I was surprised to learn that this famous digital media theorist is currently obsessed with a print-based initiative. His new Mediaworks Pamphlets are “theoretical fetish objects for the 21st century” – elegantly produced collaborations between designer and writer, intended to break serious media theory out of “the hermetically sealed spheres of academia and the techno-culture” and into the public discourse, much like the famous collaboration between Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, “The Medium is the Massage.” By shifting reading, writing and design practices to the screen, Lunenfeld argues, digital media have effectively “taken the weight off” of the print codex, enabling its tactile qualities to flower anew.  There is room now to play and invent in the realm of paper, and a resulting emphasis on the pursuit of pleasure and grace in the experience of book objects. As evidence of the resurgent fetish book, Lunenfeld points to the immaculate productions of McSweeney’s, which has made its mark by coupling serious literary output with elegant design at relatively low cost to the reader.

There is room now to play and invent in the realm of paper, and a resulting emphasis on the pursuit of pleasure and grace in the experience of book objects. As evidence of the resurgent fetish book, Lunenfeld points to the immaculate productions of McSweeney’s, which has made its mark by coupling serious literary output with elegant design at relatively low cost to the reader.

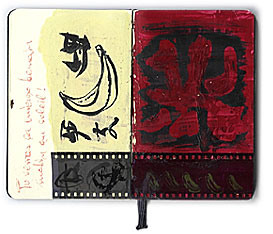

Another sign of this resurgence is the Moleskine phenomenon – those indelible oilskin-bound notebooks reissued in 1998 from the classic French design, famously employed by Chatwin in his travels, and, if the packaging is to be believed, by Hemingway, Van Gogh and Picasso as well.  Nowadays, Moleskines are favored by aesthetes and design sophisticates with a propensity for jotting things down, and is especially beloved by the blogging and techie communities, further evidence that this renewed fetish interest is intimately linked to the experience of networked, digital culture. In fact, Moleskine culture is a flourishing niche on the web, with blogs, art sites, and a full Wikipedia entry devoted solely to the flights of invention (Moleskine hacks etc.) and cult of personal record-keeping arising from this little black book.

Nowadays, Moleskines are favored by aesthetes and design sophisticates with a propensity for jotting things down, and is especially beloved by the blogging and techie communities, further evidence that this renewed fetish interest is intimately linked to the experience of networked, digital culture. In fact, Moleskine culture is a flourishing niche on the web, with blogs, art sites, and a full Wikipedia entry devoted solely to the flights of invention (Moleskine hacks etc.) and cult of personal record-keeping arising from this little black book.

Returning to Lunenfeld’s fetish theory with McSweeney’s as exemplar, it’s almost too perfect that McSweeney’s founder Dave Eggers’ new book of short stories, How We Are Hungry, should be bound exactly like a Moleskine, complete with elastic fastening band. But whereas my notebooks have held up admirably through miles of travel and years of abuse, the elastic strap of my copy of the Eggers book broke after a single day’s jostling in my bag. Take note, McSweeney’s…