Wired profiles Amp’d Mobile, a new service launching this fall that will offer subscribers a wide array of “mobile entertainment” options on a specialized handheld device. Amp’d has marshalled a vast amount of venture capital to bring the cellphone to its full potential as a catch-all media device – video console, gaming handset, ebook reader, web browser, and, if your brain hasn’t been totally fricasseed by that point, still a good old-fashioned telephone.

Amp’d targets consumers in their mid-20s to mid-30s – the bracket that is the most gadget-crazed, the most entertainment-hungry, as well as the most mobile, or so the reasoning goes. At the very least, Amp’d might serve as a catalyst for Verizon, Sprint and the other big mobile service providers to move into this sweet spot of media convergence. It certainly seems that things are going that way.

Category Archives: The Ideal Device?

play station portable as online reading device

The new updated Sony PSP portable gaming device will include a web browser. That gives it games, film, photo and web – the most comprehensive pocket instrument out there. But for the time being, it’s read-only. Without a stylus, or virtual keyboard, many of the web’s more interactive elements will be unavailable.

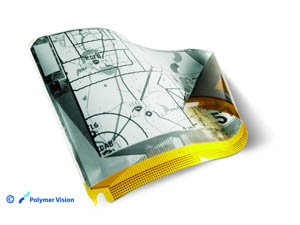

rollable paper-like screens

![]()

Some future fantasy fare from Polymer Vision, a subset of Philips. These screens are paper-thin and use e-ink to produce a reflective display that consumes little power and can be read in sunlight. Read a book and then roll it back up into your phone. This stuff is only a few years off.

![]()

More info from Philips.

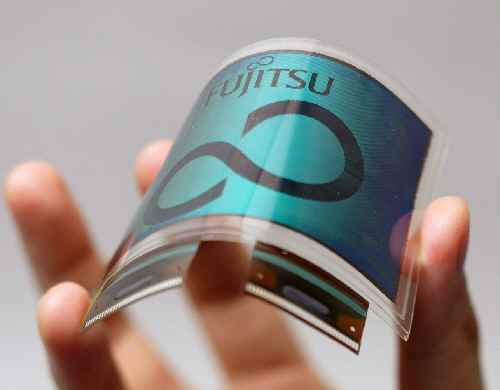

curvaceous electronic paper, with color

Fujitsu has developed a flexible, light-weight electronic display capable of retaining stable, full-color images even when bent. About as thick as a plastic transparency (like an x-ray), the paper consists of three substrate layers (red, green and blue) and requires “only one one-hundredth to one ten-thousandth the energy of conventional display technologies.” The paper’s memory system enables continuous image display with zero energy required, while changing images consumes only a negligible amount of power. And because displays won’t require continuous updates, Fujitsu boasts, the screen will not flicker. The paper should be available to consumers by Spring, 2006. It will be pushed for use in the office, home and for signs and advertisements in public spaces. It’s not clear, however, if it will be able to handle film or sophisticated animation (I would guess not very well). If anyone reading this happens to be in Tokyo today or tomorrow, the prototype is currently being exhibited at the Fujitsu Forum.

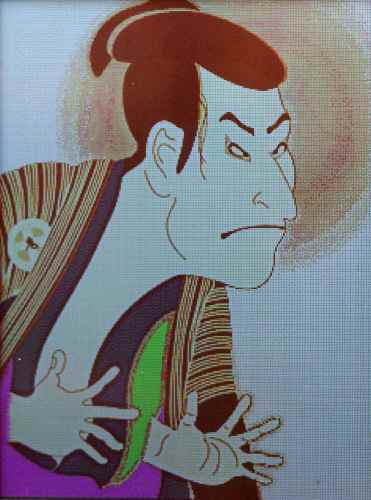

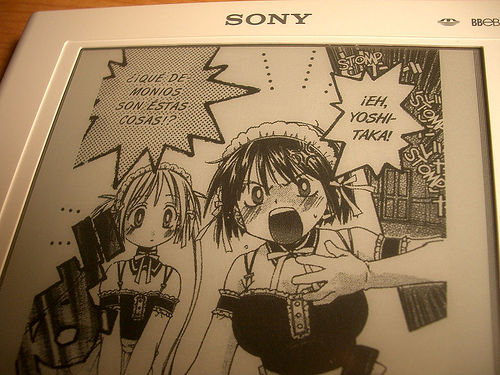

reading manga on Sony Librie

Came across this Flickr photoset of Japanese comics on a Librie – Sony’s electric ink ebook reader. Even in a photo, the reflective, print-like quality of the screen is striking. People have generally raved about the Librie’s display, but are outraged by its senseless DRM policies: books self-destruct after 60 days. (discussed here and here)

Once E ink enters the mainstream, people might flock to electronic books as rapidly and enthusiastically as they did to digital photography. Screen display technology will undoubtedly advance. The DRM problem is trickier.

(Incidentally, I found this image while browsing recent blog posts under the “ebook” tag on Technorati. Flickr images tagged with “ebook” are placed alongside. An example of how these social tagging systems are becoming interconnected.)

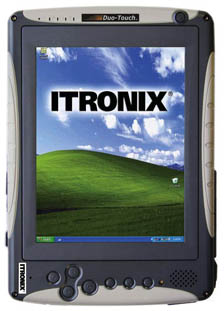

a computer to withstand the wind and rain

This expensive new tablet PC is built to withstand “rain, snow, wind, dust, vibration, shock, chemical exposure, and temperature extremes, from minus 4 to 140 degrees” (see article).

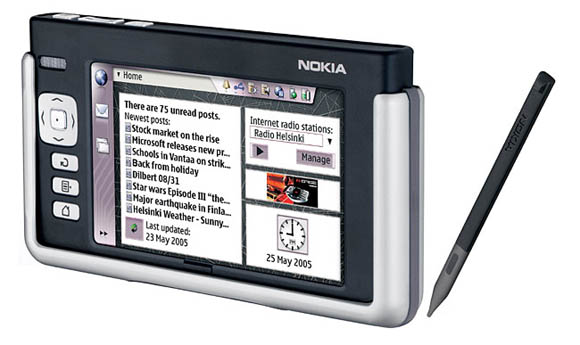

devices converge

![]() Nokia is preparing to release the Internet Tablet, a handheld, Linux-based device with wireless web browsing capability and a variety of multimedia options (video, audio, internet radio). $350 is the asking price. Problems seem to be that it doesn’t come with a lot of memory, and that it doesn’t support Microsoft media formats. But it edges a little closer to the “can I take it into bed with me?” criterion. We’ll see if any interesting e-reading formats are developed for it. Most likely just a footnote on the way to something better.

Nokia is preparing to release the Internet Tablet, a handheld, Linux-based device with wireless web browsing capability and a variety of multimedia options (video, audio, internet radio). $350 is the asking price. Problems seem to be that it doesn’t come with a lot of memory, and that it doesn’t support Microsoft media formats. But it edges a little closer to the “can I take it into bed with me?” criterion. We’ll see if any interesting e-reading formats are developed for it. Most likely just a footnote on the way to something better.

Mentioned here in Wired. Here with the Linux angle. Pros and cons laid out here.

mobile web initiative

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the main standards-setting body for the networked world we live and breathe, recently launched the Mobile Web Initiative. From the press release:

“Many of today’s mobile devices already feature Web browsers and the demand for mobile devices continues to grow. Despite these trends, browsing the Web from a mobile device — for example, to find product information, consult timetables, check email, transfer money — has not become as convenient as expected. Users often find that their favorite Web sites are not accessible or not as easy to use on their mobile phone as on their desktop computer. Content providers have difficulties building Web sites that work well on all types and configurations of mobile phones offering Web access.”

The web is moving further and further from being exclusively a desktop system. What began essentially as a set of interlinked brochures, to be read sitting down, has evolved into a dynamic, social multimedia space, increasingly connected to the world around us. I often think of the history of industrialization as a story of estrangement from the physical world. Cities swell, smog billows and the haze of electric light washes out the stars. Mass media forms naturally emerge from the concentration of industry – economies of scale that favor homogeneity, the sweeping gesture. At first, the new media seem to take this estrangement further, confining us to “virtual” spaces. But quite to the contrary, the web is taking us back into the world, not out of it. Even something as simple as Google Maps suggests this return. But to become fully unmoored from our desks, standards have to be set in place to ensure that the web is readable in smaller formats, and that we have faster, more reliable access when we’re on the move. Plus, the devices need to emerge that offer the convenience of a cell phone with the power of a notebook computer. The future of personal computing lies more with cell phones (see the new Sidekick II), iPods and Play Station Portable than with the latest desktop from Dell or Apple.

reading, without the book

David Bell, a history professor at Johns Hopkins, has written a smart, well-reasoned article for The New Republic entitled “The Bookless Future,” in which he ponders the changing nature of reading, writing and research in a digital world. Professor Bell and The New Republic have kindly allowed us to reproduce the article in TK3, an e-document reader. Our hope is that it will serve as a springboard for wider discussion, both of the article, and of what is needed to create the optimal electronic reading environment. The downloads are below, followed by some initial thoughts on Bell’s piece. We would love to hear people’s reactions..

First Download and Install the TK3 Reader

- TK3 Reader Installer WINDOWS

- TK3 Reader Installer MAC OSX (if using Internet Explorer, hold down the option-key when downloading for the Mac)

Then Download “The Bookless Future”

(when you’ve unzipped the book, you should be able to open it by double-clicking on its icon)

In Bell’s view, the big gains so far have been in the realm of research. “Today, a scholar in South Dakota, or Shanghai, or Albania–anywhere on earth with an Internet connection–has a research library at her fingertips.” A democratization has taken place, comparable only to the change unleashed by the printing press. The ease and speed of searching, comparing, and collating digital documents is similarly a great boon to scholars and students. The benefits afforded by new reading modes far outnumber the losses that opponents of the electronic book frequently lament – the tactile pleasures, the smell of musty bindings, the social environment of bookstores, the art of typography.

This will remain controversial territory for quite some time, but Bell manages to strike the right balance:

What really matters, particularly at this early stage, is not to damn or to praise the eclipse of the paper book or the digital complication of its future, but to ensure that it happens in the right way, and to minimize the risks.

Bell is also thinking what this means for writing. He recognizes the possibilities for new kinds of expression and argumentation that are only possible in the multimedia, not-exclusively-linear, environment of the computer. He cites a few examples in the Gutenberg-e series. But Bell’s enthusiasm is mixed with concern for how we are being affected as readers. First there is the way we absorb content, which has been entirely transformed by hypertext and search – the “browsing” ethos. Bell warns:

Reading in this strategic, targeted manner can feel empowering. Instead of surrendering to the organizing logic of the book you are reading, you can approach it with your own questions and glean precisely what you want from it. You are the master, not some dead author. And this is precisely where the greatest dangers lie, because when reading, you should not be the master. Information is not knowledge; searching is not reading; and surrendering to the organizing logic of a book is, after all, the way one learns.

Questions of form are no less important. Bell reminds us that the digital revolution, unlike the print revolution, is not just about the book. Moveable type may have transformed the means of production for books. But in form, they remained basically the same, and were no less “readable” than their hand-copied forebears. This is not the case with digital books. Until personal computers, and later, the web, it was never assumed that we would do any serious reading on screens. But as technology advanced, we learned that computers were more than just computational tools. A big lesson of the digital revolution is that since all media can be equalized as ones and zeros, then it follows that all media can converge and dance together in a single space. The digital revolution is about this convergence. Text is just one part of it, and so far computers have proven themselves better at handling rich media like graphics, film and sound than at providing satisfactory conditions for sustained reading. This boils down to a few, very simple reasons:

1. Screen display technology is poor – it hurts the eyes, requires large amounts of energy, and cannot be read in sunlight or other such ambient light settings. Progress is being made with the development of electronic ink and cholesteric displays, and Bell hopes that these improvements will deliver us from the headache of liquid crystal displays.

2. Most electronic documents are read in vertical scrolling fields. This is probably descended from the first computer terminal reading which consisted of long batches of code, best read in a scroll, or spit out on long rolls of paper. Horizontal paging keeps words and lines in a fixed position and makes for much easier reading. But you rarely find this today. A good example is the website of the International Herald Tribune. It seems like a no-brainer that screen-based documents should be laid out in this way.

3. And finally, the device is too awkward – heavy, fragile, expensive, and overheated.

Bell recognizes these points, but overemphasizes the need for a device that is tailored exclusively for screen-reading (though he does acknowledge that it would require web-browsing capabilities). One of the reasons book reading devices have consistently failed to catch on is that they are too specialized. In digital space, media can dance together, and there is no reason to corral them off into distinct zones. People are already reading books and other documents on their PDAs, and even their cell phones (check out thread, “the ideal device“). This is not because they offer an ideal reading environment, but because they are indispensable – gadgets that you always have with you. As a consequence, people feel compelled to cram in as many uses as possible. By this logic, the cell phone and the laptop seemed destined to combine. It may end up being something roughly the size of a trade paperback – hold it vertically to read a text, or flip it on its side to watch a widescreen film or play a video game. As with media, it seems inevitable that devices, too, will eventually converge.

ebooks in education

![]() if:book will be spending the day at the Open eBook Forum‘s eBooks in Education Conference at the McGraw-Hill Auditorium in New York.

if:book will be spending the day at the Open eBook Forum‘s eBooks in Education Conference at the McGraw-Hill Auditorium in New York.

In the spirit of the conference, here’s an AP article from last week that gives a good overview of Nicholas Negroponte‘s $100 laptop project for developing countries.

“Details are still being worked out, but here’s the MIT team’s current recipe: Put the laptop on a software diet; use the freely distributed Linux operating system; design a battery capable of being recharged with a hand crank; and use newly developed ‘electronic ink’ or a novel rear-projected image display with a 12-inch screen. Then, give it Wi-Fi access, and add USB ports to hook up peripheral devices. Most importantly, take profits, sales costs and marketing expenses out of the picture.”