A quite note to point out that LACMA has announced that they’ve posted the long out-of-print catalogue for their 1971 Art and Technology show online in its entirety in both web and PDF format. It’s worth looking at: Maurice Tuchman and Jane Livingston, the curators of the show, attempted to match artists from the 1960s with corporations working with technology to see what would happen. The process of collaboration is an integral part of the documentation of the project. Sometimes attempted collaborations didn’t work out, and their failure is represented in a refreshingly candid fashion: John Baldessari wanted to work in a botany lab coloring plants; George Brecht wanted IBM & Rand’s help to move the British Isles into the Mediterranean; Donald Judd seems to have wandered off in California. And some of the collaborations worked: Andy Warhol made holograms; Richard Serra worked with a steel foundry; and Jackson Mac Low worked with programmers from IBM to make concrete poetry, among many others.

A quite note to point out that LACMA has announced that they’ve posted the long out-of-print catalogue for their 1971 Art and Technology show online in its entirety in both web and PDF format. It’s worth looking at: Maurice Tuchman and Jane Livingston, the curators of the show, attempted to match artists from the 1960s with corporations working with technology to see what would happen. The process of collaboration is an integral part of the documentation of the project. Sometimes attempted collaborations didn’t work out, and their failure is represented in a refreshingly candid fashion: John Baldessari wanted to work in a botany lab coloring plants; George Brecht wanted IBM & Rand’s help to move the British Isles into the Mediterranean; Donald Judd seems to have wandered off in California. And some of the collaborations worked: Andy Warhol made holograms; Richard Serra worked with a steel foundry; and Jackson Mac Low worked with programmers from IBM to make concrete poetry, among many others.

One contributor who might be unexpected in this context is Jeff Raskin (his first name later lost an “f”), who at the time was an arts professor at UCSD; he’s now best known as the guy behind the Apple Macintosh’s interface. We’ve mentioned his zooming interface and work on humane interfaces for computers on if:book in the past; if you’ve never looked at his zoom demo, it’s worth a look. Back in 1971, he was trying to make modular units that didn’t restrict the builder’s designs; it didn’t quite get off the ground. Microcomputers would come along a few years later.

Category Archives: technology

from work to text

I spent the weekend before last at the Center for Book Arts as part of their Fine Press Publishing Seminar for Emerging Writers. There I was taught to set type; not, perhaps, exactly what you’d expect from someone writing for a blog devoted to new technology. Robert Bringhurst, speaking about typography a couple years back, noted that one of typography’s virtues in the modern world is its status as a “mature technology”; as such, it can serve as a useful measuring stick for those emerging. A chance to think, again, about how books are made: a return to the roots of publishing technology might well illuminate the way we think about the present and future of the book.

I’ve been involved with various aspects of making books – from writing to production – for just over a decade now. In a sense, this isn’t very long – all the books I’ve ever been involved with have gone through a computer – but it’s long enough to note how changes in technology affect the way that books are made. Technology’s changed rapidly over the last decade; I know that my ability to think through them has barely kept up. An arbitrary chronology, then, of my personal history with publishing technology.

The first book I was involved in was Let’s Go Ireland 1998, for which I served as an associate editor in the summer of 1999. At that point, Let’s Go researcher/writers were sent to the field with a copious supply of lined paper and a two copies of the previous year’s book; they cut one copy up and glued it to sheets of paper with hand-written changes, which were then mailed back to the office in Cambridge. A great deal of the associate editor’s job was to type in the changes to the previous years’ book; if you were lucky, typists could be hired to take care of that dirty work. I was not, it goes without saying, a very good typist; my mind tended to drift unless I were re-editing the text. A lot of bad jokes found their way into the book; waves of further editing combed some of them out and let others in. The final text printed that fall bore some resemblance to what the researcher had written, but it was as much a product of the various editors who worked on the book.

The next summer I found myself back at Let’s Go; for lack of anything better to do and a misguided personal masochism I became the Production Manager, which meant (at that point in time) that I oversaw the computer network and the typesetting of the series. Let’s Go, at that point, was a weirdly forward-looking publishing venture in that the books were entirely edited and typeset before they were handed over to St. Martin’s Press for printing and distribution. Because everything was done on an extremely tight schedule – books were constructed from start to finish over the course of a summer – editors were forced to edit in the program used for layout, Adobe FrameMaker, an application intended for creating industrial documentation. (This isn’t, it’s worth pointing out, the way most of the publishing industry works.) That summer, we began a program to give about half the researchers laptops – clunky beige beasts with almost no battery life – to work on; I believe they did their editing on Microsoft Word and mailed 3.5” disks back to the office, where the editors would convert them to Frame. A change happened there: those books were, in a sense, born digital. The translation of handwriting into text in a computer no longer happened. A word was typed in, transferred from computer to computer, shifted around on screen, and, if kept, sent to press, the same word, maybe.

Something ineffable was lost with the omission of the typist: to go from writing on paper to words on a screen, the word on the page has to travel through the eye of the typist, the brain, and down to the hand. The passage through the brain of the typist is an interesting one because it’s not necessarily perfect: the typist might simply let the word through, or improve the wording. Or the typist make a mistake – which did happen frequently. All travel guides are littered with mistakes; often mistakes were not the fault of a researcher’s inattentiveness or an editor’s mendaciousness but a typist’s poor transliteration. That was the argument I made the next year I applied to work at Let’s Go; a friend and I applied to research and edit the Rome book in Rome, rather then sending copy back to the office. Less transmissions, we argued, meant less mistakes. The argument was successful, and Christina and I spent the summer in Rome, writing directly in FrameMaker, editing each other’s work, and producing a book that we had almost exclusive control over, for better or worse.

It’s roughly that model which has become the dominant paradigm for most writing and publishing now: it’s rare that writing doesn’t start on a computer. The Internet (and, to a lesser extent, print-on-demand publishing services) mean that you can be your own publisher; you can edit yourself, if you feel the need. The layers that text needed to be sent through to be published have been flattened. There are good points to this and bad; in retrospect, the book we produced, full of scarcely disguised contempt for the backpackers we were ostensibly writing for, was nothing if not self-indulgent. An editor’s eye wouldn’t have hurt.

And so after a not inconsequential amount of time spent laying out books, I finally got around to learning to set type. (I don’t know that my backwardness is that unusual: with a copy of Quark or InDesign, you don’t actually need to know much of an education in graphic design to make a book.) Learning to set type is something self-consciously old-fashioned: it’s a technology that’s been replaced for all practical purposes. But looking at the world of metal type through the lens of current technology reveals things that may well have been hidden when it was dominant.

While it was suggested that the participants in the Emerging Writing Seminar might want to typeset their own Emerging Writing, I didn’t think any of my writing was worth setting in metal, so I set out to typeset some of Gertrude Stein. I’ve been making my way through her work lately, one of those over-obvious discoveries that you don’t make until too late, and I thought it would be interesting to lay out a few paragraphs of her writing. Stein’s writing is interesting to me because it forces the reader to slow down: it demands to be read aloud. There’s also a particular look to Stein’s work on a page: it has a concrete uniformness on the page that makes it recognizable as hers even when the words are illegible. Typesetting, I though, might be an interesting way to think through it, so I set myself to typeset a few paragraphs from “Orta or One Dancing”, her prose portrait of Isadora Duncan.

Typesetting, it turns out, is hard work: standing over a case of type and pulling out type to set in a compositing stick is exhausting in a way that a day of typing and clicking at a computer is not. A computer is, of course, designed to be a labor-saving device; still, it struck me as odd that the labor saved would be so emphatically physical. Choosing to work with Stein’s words didn’t make this any easier, as anyone with any sense might have foreseen: participles and repetitions blur together. Typesetting means that the text has to be copied out letter by letter: the typesetter looks at the manuscript, sees the next letter, pulls the piece of type out of the case, adds it to the line in the compositing stick. Mistakes are harder to correct than on a computer: as each line needs to be individually set, words in the wrong place mean that everything needs to be physically reshuffled. With the computer, we’ve become dependent upon copying and pasting: we take this for granted now, but it’s a relatively recent ability.

There’s no end of ways to go wrong with manual typesetting. With a computer, you type a word and it appears on a screen; with lead type, you add a word, and look at it to see if it appears correct in its backward state. Eventually you proof it on a press; individual pieces of type may be defective and need to be replaced. Lowercase bs are easily confused with ds when they’re mirrored in lead. Type can be put in upside-down; different fonts may have been mixed in the case of type you’re using. Spacing needs to be thought about: if your line of type doesn’t have exactly enough lead in it to fill it, letters may be wobbly. Ink needs attention. Paper width needs attention. After only four days of instruction, I’m sure I don’t know half of the other things that might go wrong. And at the end of it all, there’s the clean up: returning each letter to its precise place, a menial task that takes surprisingly long.

We think about precisely none of these things when using a computer. To an extent, this is great: we can think about the words and not worry about how they’re getting on the page. It’s a precocious world: you can type out a sentence and never have to think about it again. But there’s something appealing about a more altricial model, the luxury of spending two days with two paragraphs, even if it is two days of bumbling – one never spends that kind of time with a text any more. A degree of slowness is forced upon even the best manual typesetter: every letter must be considered, eye to brain to hand. With so much manual labor, it’s no surprise that there so many editorial layers existed: it’s a lot of work to fix a mistake in lead type. Last-minute revision isn’t something to be encouraged; when a manuscript arrived in the typesetter’s hands, it needs to be thoroughly finished.

Letterpress is the beginning of mechanical reproduction, but it’s still laughably inefficient: it’s still intimately connected to human labor. There’s a clue here, perhaps, to the long association between printers and progressive labor movements. A certain sense of compulsion comes from looking at a page of letterset type that doesn’t quite come, for me, from looking at something that’s photoset (as just about everything in print is now) or on a screen. It’s a sense of the physical work that went into it: somebody had to ink up a press and make those impressions on that sheet of paper. I’m not sure this is necessarily a universal reaction, although it is the same sort of response that I have when looking at something well painted knowing how hard it is to manipulate paint from my own experience. (I’m not arguing, of course, that technique by itself is an absolute indicator of value: a more uncharitable essayist could make the argument could be made that letterpress functions socially as a sort of scrapbooking for the blue states.) Maybe it’s a distrust of abstractions on my part: a website that looks like an enormous amount of work has been put into it may just as easily have stolen its content entirely from the real producers. There’s a comparable amount of work that goes into non-letterpressed text, but it’s invisible: a PDF file sent to Taiwan comes back as cartons of real books; back office workers labor for weeks or months to produce a website. In comparison, metal typesetting has a solidity to it: the knowledge that every letter has been individually handled, which is somehow comforting.

Nostalgia ineluctably works its way into any argument of this sort, and once it’s in it’s hard to pull it out. There’s something disappointing to me in both arguments blindly singing the praises of the unstoppable march of technology and those complaining that things used to be better; you see exactly this dichotomy in some of the comments this blog attracts. (Pynchon: “She had heard all about excluded middles; they were bad shit, to be avoided; and how had it ever happened here, with the chances once so good for diversity?”) A certain tension between past and present, between work and text, might be what’s needed.

why are screens square?

More from the archive, I’m afraid; but I’ve quoted this so often in the last year that it merits repeating.

A video of Jo Walsh, a simultaneously near-invisible and near-legendary hacker I met through the University of Openess in London, talking about FOAF, Web3.0, geospatial data, the ‘One Ring To Rule Them All’ tendency of so-called ‘social media’ and the philosophies of making tech tools.

“Why are screens square?”, she asks. What follows is less a set of theories as a meditation on what happens when you start trying to think back through the layers of toolmaking that go into a piece of paper, a pen, a screen, a keyboard – the media we use to represent ourselves, and that we agree to pretend are transparent. This then becomes the starting-point for another meditation on who owns, or might own, our digital future.

(High-quality video so takes a little while to load)

ecclesiastical proust archive: starting a community

(Jeff Drouin is in the English Ph.D. Program at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York)

About three weeks ago I had lunch with Ben, Eddie, Dan, and Jesse to talk about starting a community with one of my projects, the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive. I heard of the Institute for the Future of the Book some time ago in a seminar meeting (I think) and began reading the blog regularly last Summer, when I noticed the archive was mentioned in a comment on Sarah Northmore’s post regarding Hurricane Katrina and print publishing infrastructure. The Institute is on the forefront of textual theory and criticism (among many other things), and if:book is a great model for the kind of discourse I want to happen at the Proust archive. When I finally started thinking about how to make my project collaborative I decided to contact the Institute, since we’re all in Brooklyn, to see if we could meet. I had an absolute blast and left their place swimming in ideas!

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together.

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together.

For those who might not know, The Ecclesiastical Proust Archive is an online tool for the analysis and discussion of à la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time). It’s a searchable database pairing all 336 church-related passages in the (translated) novel with images depicting the original churches or related scenes. The search results also provide paratextual information about the pagination (it’s tied to a specific print edition), the story context (since the passages are violently decontextualized), and a set of associations (concepts, themes, important details, like tags in a blog) for each passage. My purpose in making it was to perform a meditation on the church motif in the Recherche as well as a study on the nature of narrative.

I think the archive could be a fertile space for collaborative discourse on Proust, narratology, technology, the future of the humanities, and other topics related to its mission. A brief example of that kind of discussion can be seen in this forum exchange on the classification of associations. Also, the church motif — which some might think too narrow — actually forms the central metaphor for the construction of the Recherche itself and has an almost universal valence within it. (More on that topic in this recent post on the archive blog).

Following the if:book model, the archive could also be a spawning pool for other scholars’ projects, where they can present and hone ideas in a concentrated, collaborative environment. Sort of like what the Institute did with Mitchell Stephens’ Without Gods and Holy of Holies, a move away from the ‘lone scholar in the archive’ model that still persists in academic humanities today.

One of the recurring points in our conversation at the Institute was that the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive, as currently constructed around the church motif, is “my reading” of Proust. It might be difficult to get others on board if their readings — on gender, phenomenology, synaesthesia, or whatever else — would have little impact on the archive itself (as opposed to the discussion spaces). This complex topic and its practical ramifications were treated more fully in this recent post on the archive blog.

I’m really struck by the notion of a “reading” as not just a private experience or a public writing about a text, but also the building of a dynamic thing. This is certainly an advantage offered by social software and networked media, and I think the humanities should be exploring this kind of research practice in earnest. Most digital archives in my field provide material but go no further. That’s a good thing, of course, because many of them are immensely useful and important, such as the Kolb-Proust Archive for Research at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Some archives — such as the NINES project — also allow readers to upload and tag content (subject to peer review). The Ecclesiastical Proust Archive differs from these in that it applies the archival model to perform criticism on a particular literary text, to document a single category of lexia for the experience and articulation of textuality.

If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.

If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.

If the archive continues to be built along the church motif, there might be enough work to interest collaborators. The enhancements I currently envision include a French version of the search engine, the translation of some of the site into French, rewriting the search engine in PHP/MySQL, creating a folksonomic functionality for passages and images, and creating commentary space within the search results (and making that searchable). That’s some heavy work, and a grant would probably go a long way toward attracting collaborators.

So my sense is that the Proust archive could become one of two things, or two separate things. It could continue along its current ecclesiastical path as a focused and led project with more-or-less particular roles, which might be sufficient to allow collaborators a sense of ownership. Or it could become more encyclopedic (dare I say catholic?) like a wiki. Either way, the organizational and logistical practices would need to be carefully planned. Both ways offer different levels of open-endedness. And both ways dovetail with the very interesting discussion that has been happening around Ben’s recent post on the million penguins collaborative wiki-novel.

Right now I’m trying to get feedback on the archive in order to develop the best plan possible. I’ll be demonstrating it and raising similar questions at the Society for Textual Scholarship conference at NYU in mid-March. So please feel free to mention the archive to anyone who might be interested and encourage them to contact me at jdrouin@gc.cuny.edu. And please feel free to offer thoughts, comments, questions, criticism, etc. The discussion forum and blog are there to document the archive’s development as well.

Thanks for reading this very long post. It’s difficult to do anything small-scale with Proust!

the good life: part 1

The Van Alen Institute has organized an exhibition that explores new design and use of public space for recreation. The exhibition displays innovative designs for reimagined and reclaimed public spaces from various architects and urban planners. The projects are organized into five categories: The Connected City, the Cultural City, the 24-Hour City, the Fun City, and the Healthy City. As part of the exhibition, the Van Alen Institute has been holding weekly panel discussions about designing public space from international and local (NYC) perspectives. The participants have been high level partners in some of the most widely regarded architecture firms in NYC and the world. The questions and discussions afterwards, however, have proved to be the most interesting part; there have been questions about autonomy and conformity in public space, and how much of the new public space has been designed for safety, but little else. They have become ‘non-spaces’, and fail to support public needs for engagement, relaxation, and health.

This week their discussion will move away from the architectural and planning and into new technology. It will be interesting to see how technology supports and influences ideas of connectedness in a public place; while the value of connecting to others from a private, isolated space seems obvious, doing so from a public place seems less common and less intuitive than face-to-face interaction. The panel, including Christina Ray (responsible for the Conflux Festival ) and Nick Fortugno (Come Out & Play Festival), will present and discuss “The Wired City” at 6:30 pm on Wednesday, Sep. 27.

love through networked screens

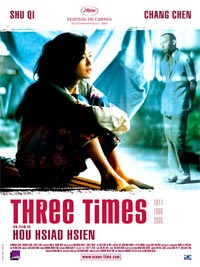

This past weekend, I saw a remarkable film: “Three Times,” by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. It’s a triptych on love set in Taiwan in three separate periods — 1966, 1911, and 2005 — each section focusing on a young man and woman, played by the same actors. Hou does incredible things with time. Each of the episodes, in fact, is a sort of study in time, not just of a specific time in history, but in the way time moves in love relationships. The opening shots of the first episode, “A Time for Love,” announce that things will be operating in a different temporal register. Billiard balls glide across a table. You don’t yet understand the rules of the game that is being played. Characters gradually emerge and the story unfolds through strange compressions and contractions of time that comprise a weird logic of yearning.

This past weekend, I saw a remarkable film: “Three Times,” by Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. It’s a triptych on love set in Taiwan in three separate periods — 1966, 1911, and 2005 — each section focusing on a young man and woman, played by the same actors. Hou does incredible things with time. Each of the episodes, in fact, is a sort of study in time, not just of a specific time in history, but in the way time moves in love relationships. The opening shots of the first episode, “A Time for Love,” announce that things will be operating in a different temporal register. Billiard balls glide across a table. You don’t yet understand the rules of the game that is being played. Characters gradually emerge and the story unfolds through strange compressions and contractions of time that comprise a weird logic of yearning.

This is the first of Hou’s films that I’ve seen (it’s only the second to secure an American release). I was reminded of Tarkovsky in the way Hou uses cinema to convey the movement of time, both across the eras and within individual episodes. There’s much to say about this film, and I hope to see it again to better figure out how it does what it does. The reason I bring it up here is that the third story — “A Time for Youth,” set in contemporary Taipei — contains some of the most profound and visually arresting depictions of the mediation of intimate relationships through technology that I’ve ever seen. Cell-phones and computers have been popping up in movies for some time now, usually for the purposes of exposition or for some spooky haunted technology effect, like in “The Matrix” or “The Ring.” In “Three Times,” these new modes of contact are probed more deeply.

The story involves a meeting of an epileptic lounge punk singer and an admiring photographer, while the singer’s jilted female lover lurks in the margins.  Hou weaves back and worth between intense face-to-face meetings and asynchronous electronic communication. At various times, the screen of the movie theater (the IFC in Greenwich Village) is completely filled with an extreme close-up of a cell-phone screen or a computer monitor, the text of an SMS or email message as big as billboard lettering. The pixelated Chinese characters are enormous and seem to quiver, or to be on the verge of melting. A cursor blinking at the end of an alleged suicide note typed into a computer is a dangling question of life and death, or perhaps just a sulky dramatic gesture.

Hou weaves back and worth between intense face-to-face meetings and asynchronous electronic communication. At various times, the screen of the movie theater (the IFC in Greenwich Village) is completely filled with an extreme close-up of a cell-phone screen or a computer monitor, the text of an SMS or email message as big as billboard lettering. The pixelated Chinese characters are enormous and seem to quiver, or to be on the verge of melting. A cursor blinking at the end of an alleged suicide note typed into a computer is a dangling question of life and death, or perhaps just a sulky dramatic gesture.

What’s especially interesting is that the most expressive speech in “A Time for Youth” is delivered electronically. Face-to-face meetings are more muted and indirect. There’s an eerie episode in a nightclub where the singer is performing on stage while the photographer and another man circle her with cameras, moving as close as they can without actually touching her, shooting photos point blank.

But it was the use of screens that really struck me. By filling our entire field of vision with them — you almost feel like you’re swimming in pixels — Hou conveys how tiny channels of mediated speech can carry intense, all-consuming feeling. The weird splotchiness of digital text at close range speaks of great vulnerability. Similarly, the revelation of the singer’s epilepsy is not through direct disclosure, but happens by accident when she leaves behind a card with instructions for what to do in case of a seizure, after spending the night at the photographer’s apartment. This all strikingly follows up the previous episode, “A Time for Freedom,” which is done as a silent film with all the dialogue conveyed on placards.

It’s one of those things that suddenly you viscerally understand when a great artist shows you: how these technologies spin a web of time around us, sending voices and gestures across space instantly, but also placing a veil between people when they actually share a space. In many ways, these devices bring us closer, but they also fracture our attention and further insulate us. Never are you totally apart, but seldom are you totally together.

“Three Times” is currently out in a few cities across the US and rolling out progressively through June in various independent movie houses (more info here).

this is exciting.

every once in a while we see something that quickens the pulse. Jefferson Han, a researcher at NYU’s Computer Science Dept. has made a video showing a system which allows someone to manipulate objects in real time using all the fingers of both hands. watch the video and get a sense of what it will be like to be able to manipulate data in two and someday three dimensions by using intuitive body gestures.

illusions of a borderless world

A number of influential folks around the blogosphere are reluctantly endorsing Google’s decision to play by China’s censorship rules on its new Google.cn service — what one local commentator calls a “eunuch version” of Google.com. Here’s a sampler of opinions:

Ethan Zuckerman (“Google in China: Cause For Any Hope?”):

It’s a compromise that doesn’t make me happy, that probably doesn’t make most of the people who work for Google very happy, but which has been carefully thought through…

In launching Google.cn, Google made an interesting decision – they did not launch versions of Gmail or Blogger, both services where users create content. This helps Google escape situations like the one Yahoo faced when the Chinese government asked for information on Shi Tao, or when MSN pulled Michael Anti’s blog. This suggests to me that Google’s willing to sacrifice revenue and market share in exchange for minimizing situations where they’re asked to put Chinese users at risk of arrest or detention… This, in turn, gives me some cause for hope.

Rebecca MacKinnon (“Google in China: Degrees of Evil”):

At the end of the day, this compromise puts Google a little lower on the evil scale than many other internet companies in China. But is this compromise something Google should be proud of? No. They have put a foot further into the mud. Now let’s see whether they get sucked in deeper or whether they end up holding their ground.

David Weinberger (“Google in China”):

If forced to choose — as Google has been — I’d probably do what Google is doing. It sucks, it stinks, but how would an information embargo help? It wouldn’t apply pressure on the Chinese government. Chinese citizens would not be any more likely to rise up against the government because they don’t have access to Google. Staying out of China would not lead to a more free China.

Doc Searls (“Doing Less Evil, Possibly”):

I believe constant engagement — conversation, if you will — with the Chinese government, beats picking up one’s very large marbles and going home. Which seems to be the alternative.

Much as I hate to say it, this does seem to be the sensible position — not unlike opposing America’s embargo of Cuba. The logic goes that isolating Castro only serves to further isolate the Cuban people, whereas exposure to the rest of the world — even restricted and filtered — might, over time, loosen the state’s monopoly on civic life. Of course, you might say that trading Castro for globalization is merely an exchange of one tyranny for another. But what is perhaps more interesting to ponder right now, in the wake of Google’s decision, is the palpable melancholy felt in the comments above. What does it reveal about what we assume — or used to assume — about the internet and its relationship to politics and geography?

A favorite “what if” of recent history is what might have happened in the Soviet Union had it lasted into the internet age. Would the Kremlin have managed to secure its virtual borders? Or censor and filter the net into a state-controlled intranet — a Union of Soviet Socialist Networks? Or would the decentralized nature of the technology, mixed with the cultural stirrings of glasnost, have toppled the totalitarian state from beneath?

Ten years ago, in the heady early days of the internet, most would probably have placed their bets against the Soviets. The Cold War was over. Some even speculated that history itself had ended, that free-market capitalism and democracy, on the wings of the information revolution, would usher in a long era of prosperity and peace. No borders. No limits.

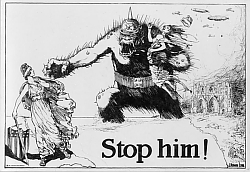

“Jingjing” and “Chacha.” Internet police officers from the city of Shenzhen who float over web pages and monitor the cyber-traffic of local users.

It’s interesting now to see how exactly the opposite has occurred. Bubbles burst. Towers fell. History, as we now realize, did not end, it was merely on vacation; while the utopian vision of the internet — as a placeless place removed from the inequities of the physical world — has all but evaporated. We realize now that geography matters. Concrete features have begun to crystallize on this massive information plain: ports, gateways and customs houses erected, borders drawn. With each passing year, the internet comes more and more to resemble a map of the world.

Those of us tickled by the “what if” of the Soviet net now have ourselves a plausible answer in China, who, through a stunning feat of pipe control — a combination of censoring filters, on-the-ground enforcement, and general peering over the shoulders of its citizens — has managed to create a heavily restricted local net in its own image. Barely a decade after the fall of the Iron Curtain, we have the Great Firewall of China.

And as we’ve seen this week, and in several highly publicized instances over the past year, the virtual hand of the Chinese government has been substantially strengthened by Western technology companies willing to play by local rules so as not to be shut out of the explosive Chinese market. Tech giants like Google, Yahoo! , and Cisco Systems have proved only too willing to abide by China’s censorship policies, blocking certain search returns and politically sensitive terms like “Taiwanese democracy,” “multi-party elections” or “Falun Gong”. They also specialize in precision bombing, sometimes removing the pages of specific users at the government’s bidding. The most recent incident came just after New Year’s when Microsoft acquiesced to government requests to shut down the My Space site of popular muckraking blogger Zhao Jing, aka Michael Anti.

One of many angry responses that circulated the non-Chinese net in the days that followed.

We tend to forget that the virtual is built of physical stuff: wires, cable, fiber — the pipes. Whoever controls those pipes, be it governments or telecomms, has the potential to control what passes through them. The result is that the internet comes in many flavors, depending in large part on where you are logging in. As Jack Goldsmith and Timothy Wu explain in an excellent article in Legal Affairs (adapted from their forthcoming book Who Controls the Internet? : Illusions of a Borderless World), China, far from being the boxed-in exception to an otherwise borderless net, is actually just the uglier side of a global reality. The net has been mapped out geographically into “a collection of nation-state networks,” each with its own politics, social mores, and consumer appetites. The very same technology that enables Chinese authorities to write the rules of their local net enables companies around the world to target advertising and gear services toward local markets. Goldsmith and Wu:

…information does not want to be free. It wants to be labeled, organized, and filtered so that it can be searched, cross-referenced, and consumed….Geography turns out to be one of the most important ways to organize information on this medium that was supposed to destroy geography.

Who knows? When networked devices truly are ubiquitous and can pinpoint our location wherever we roam, the internet could be censored or tailored right down to the individual level (like the empire in Borges’ fable that commissions a one-to-one map of its territory that upon completion perfectly covers every corresponding inch of land like a quilt).

The case of Google, while by no means unique, serves well to illustrate how threadbare the illusion of the borderless world has become. The company’s famous credo, “don’t be evil,” just doesn’t hold up in the messy, complicated real world. “Choose the lesser evil” might be more appropriate. Also crumbling upon contact with air is Google’s famous mission, “to make the world’s information universally accessible and useful,” since, as we’ve learned, Google will actually vary the world’s information depending on where in the world it operates.

Google may be behaving responsibly for a corporation, but it’s still a corporation, and corporations, in spite of well-intentioned employees, some of whom may go to great lengths to steer their company onto the righteous path, are still ultimately built to do one thing: get ahead. Last week in the States, the get-ahead impulse happened to be consonant with our values. Not wanting to spook American users, Google chose to refuse a Dept. of Justice request for search records to aid its anti-pornography crackdown. But this week, not wanting to ruffle the Chinese government, Google compromised and became an agent of political repression. “Degrees of evil,” as Rebecca MacKinnon put it.

The great irony is that technologies we romanticized as inherently anti-tyrannical have turned out to be powerful instruments of control, highly adaptable to local political realities, be they state or market-driven. Not only does the Chinese government use these technologies to suppress democracy, it does so with the help of its former Cold War adversary, America — or rather, the corporations that in a globalized world are the de facto co-authors of American foreign policy. The internet is coming of age and with that comes the inevitable fall from innocence. Part of us desperately wanted to believe Google’s silly slogans because they said something about the utopian promise of the net. But the net is part of the world, and the world is not so simple.

what I heard at MIT

Over the next few days I’ll be sifting through notes, links, and assorted epiphanies crumpled up in my pocket from two packed, and at times profound, days at the Economics of Open Content symposium, hosted in Cambridge, MA by Intelligent Television and MIT Open CourseWare. For now, here are some initial impressions — things I heard, both spoken in the room and ricocheting inside my head during and since. An oral history of the conference? Not exactly. More an attempt to jog the memory. Hopefully, though, something coherent will come across. I’ll pick up some of these threads in greater detail over the next few days. I should add that this post owes a substantial debt in form to Eliot Weinberger’s “What I Heard in Iraq” series (here and here).

![]()

Naturally, I heard a lot about “open content.”

I heard that there are two kinds of “open.” Open as in open access — to knowledge, archives, medical information etc. (like Public Library of Science or Project Gutenberg). And open as in open process — work that is out in the open, open to input, even open-ended (like Linux, Wikipedia or our experiment with MItch Stephens, Without Gods).

I heard that “content” is actually a demeaning term, treating works of authorship as filler for slots — a commodity as opposed to a public good.

I heard that open content is not necessarily the same as free content. Both can be part of a business model, but the defining difference is control — open content is often still controlled content.

I heard that for “open” to win real user investment that will feedback innovation and even result in profit, it has to be really open, not sort of open. Otherwise “open” will always be a burden.

I heard that if you build the open-access resources and demonstrate their value, the money will come later.

I heard that content should be given away for free and that the money is to be made talking about the content.

I heard that reputation and an audience are the most valuable currency anyway.

I heard that the academy’s core mission — education, research and public service — makes it a moral imperative to have all scholarly knowledge fully accessible to the public.

I heard that if knowledge is not made widely available and usable then its status as knowledge is in question.

I heard that libraries may become the digital publishing centers of tomorrow through simple, open-access platforms, overhauling the print journal system and redefining how scholarship is disseminated throughout the world.

![]()

And I heard a lot about copyright…

I heard that probably about 50% of the production budget of an average documentary film goes toward rights clearances.

I heard that many of those clearances are for “underlying” rights to third-party materials appearing in the background or reproduced within reproduced footage. I heard that these are often things like incidental images, video or sound; or corporate logos or facades of buildings that happen to be caught on film.

I heard that there is basically no “fair use” space carved out for visual and aural media.

I heard that this all but paralyzes our ability as a culture to fully examine ourselves in terms of the media that surround us.

I heard that the various alternative copyright movements are not necessarily all pulling in the same direction.

I heard that there is an “inter-operability” problem between alternative licensing schemes — that, for instance, Wikipedia’s GNU Free Documentation License is not inter-operable with any Creative Commons licenses.

I heard that since the mass market content industries have such tremendous influence on policy, that a significant extension of existing copyright laws (in the United States, at least) is likely in the near future.

I heard one person go so far as to call this a “totalitarian” intellectual property regime — a police state for content.

I heard that one possible benefit of this extension would be a general improvement of internet content distribution, and possibly greater freedom for creators to independently sell their work since they would have greater control over the flow of digital copies and be less reliant on infrastructure that today only big companies can provide.

I heard that another possible benefit of such control would be price discrimination — i.e. a graduated pricing scale for content varying according to the means of individual consumers, which could result in fairer prices. Basically, a graduated cultural consumption tax imposed by media conglomerates

I heard, however, that such a system would be possible only through a substantial invasion of users’ privacy: tracking users’ consumption patterns in other markets (right down to their local grocery store), pinpointing of users’ geographical location and analysis of their socioeconomic status.

I heard that this degree of control could be achieved only through persistent surveillance of the flow of content through codes and controls embedded in files, software and hardware.

I heard that such a wholesale compromise on privacy is all but inevitable — is in fact already happening.

I heard that in an “information economy,” user data is a major asset of companies — an asset that, like financial or physical property assets, can be liquidated, traded or sold to other companies in the event of bankruptcy, merger or acquisition.

I heard that within such an over-extended (and personally intrusive) copyright system, there would still exist the possibility of less restrictive alternatives — e.g. a peer-to-peer content cooperative where, for a single low fee, one can exchange and consume content without restriction; money is then distributed to content creators in proportion to the demand for and use of their content.

I heard that such an alternative could theoretically be implemented on the state level, with every citizen paying a single low tax (less than $10 per year) giving them unfettered access to all published media, and easily maintaining the profit margins of media industries.

I heard that, while such a scheme is highly unlikely to be implemented in the United States, a similar proposal is in early stages of debate in the French parliament.

![]()

And I heard a lot about peer-to-peer…

I heard that p2p is not just a way to exchange files or information, it is a paradigm shift that is totally changing the way societies communicate, trade, and build.

I heard that between 1840 and 1850 the first newspapers appeared in America that could be said to have mass circulation. I heard that as a result — in the space of that single decade — the cost of starting a print daily rose approximately %250.

I heard that modern democracies have basically always existed within a mass media system, a system that goes hand in hand with a centralized, mass-market capital structure.

I heard that we are now moving into a radically decentralized capital structure based on social modes of production in a peer-to-peer information commons, in what is essentially a new chapter for democratic societies.

I heard that the public sphere will never be the same again.

I heard that emerging practices of “remix culture” are in an apprentice stage focused on popular entertainment, but will soon begin manifesting in higher stakes arenas (as suggested by politically charged works like “The French Democracy” or this latest Black Lantern video about the Stanley Williams execution in California).

I heard that in a networked information commons the potential for political critique, free inquiry, and citizen action will be greatly increased.

I heard that whether we will live up to our potential is far from clear.

I heard that there is a battle over pipes, the outcome of which could have huge consequences for the health and wealth of p2p.

I heard that since the telecomm monopolies have such tremendous influence on policy, a radical deregulation of physical network infrastructure is likely in the near future.

I heard that this will entrench those monopolies, shifting the balance of the internet to consumption rather than production.

I heard this is because pre-p2p business models see one-way distribution with maximum control over individual copies, downloads and streams as the most profitable way to move content.

I heard also that policing works most effectively through top-down control over broadband.

I heard that the Chinese can attest to this.

I heard that what we need is an open spectrum commons, where connections to the network are as distributed, decentralized, and collaboratively load-sharing as the network itself.

I heard that there is nothing sacred about a business model — that it is totally dependent on capital structures, which are constantly changing throughout history.

I heard that history is shifting in a big way.

I heard it is shifting to p2p.

I heard this is the most powerful mechanism for distributing material and intellectual wealth the world has ever seen.

I heard, however, that old business models will be radically clung to, as though they are sacred.

I heard that this will be painful.

new mission statement

the institute is a bit over a year old now. our understanding of what we’re doing has deepened considerably during the year, so we thought it was time for a serious re-statement of our goals. here’s a draft for a new mission statement. we’re confident that your input can make it better, so please send your ideas and criticisms.

OVERVIEW

The Institute for the Future of the Book is a project of the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC. Starting with the assumption that the locus of intellectual discourse is shifting from printed page to networked screen, the primary goal of the Institute is to explore, understand and hopefully influence this evolution.

THE BOOK

We use the word “book” metaphorically. For the past several hundred years, humans have used print to move big ideas across time and space for the purpose of carrying on conversations about important subjects. Radio, movies, TV emerged in the last century and now with the advent of computers we are combining media to forge new forms of expression. For now, we use “book” to convey the past, the present transformation, and a number of possible futures.

THE WORK & THE NETWORK

One major consequence of the shift to digital is the addition of graphical, audio, and video elements to the written word. More profound, however, are the consequences of the relocation of the book within the network. We are transforming books from bounded objects to documents that evolve over time, bringing about fundamental changes in our concepts of reading and writing, as well as the role of author and reader.

SHORT TERM/LONG TERM

The Institute values theory and practice equally. Part of our work involves doing what we can with the tools at hand (short term). Examples include last year’s Gates Memory Project or the new author’s thinking-out-loud blogging effort. Part of our work involves trying to build new tools and effecting industry wide change (medium term): see the Sophie Project and NextText. And a significant part of our work involves blue-sky thinking about what might be possible someday, somehow (long term). Our blog, if:book covers the full-range of our interests.

CREATING TOOLS

As part of the Mellon Foundation’s project to develop an open-source digital infrastructure for higher education, the Institute is building Sophie, a set of high-end tools for writing and reading rich media electronic documents. Our goal is to enable anyone to assemble complex, elegant, and robust documents without the necessity of mastering overly complicated applications or the help of programmers.

NEW FORMS, NEW PROCESSES

Academic institutes arose in the age of print, which informed the structure and rhythm of their work. The Institute for the Future of the Book was born in the digital era, and we seek to conduct our work in ways appropriate to the emerging modes of communication and rhythms of the networked world. Freed from the traditional print publishing cycles and hierarchies of authority, the Institute seeks to conduct its activities as much as possible in the open and in real time.

HUMANISM & TECHNOLOGY

Although we are excited about the potential of digital technologies to amplify human potential in wondrous ways, we believe it is crucial to consciously consider the social impact of the long-term changes to society afforded by new technologies.

BEYOND BORDERS

Although the institute is based in the U.S. we take the seriously the potential of the internet and digital media to transcend borders. We think it’s important to pay attention to developments all over the world, recognizing that the future of the book will likely be determined as much by Beijing, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Mumbai and Accra as by New York and Los Angeles.