I spent yesterday evening in a visitors’ centre for a country that doesn’t exist. Kymaerica is a parallel universe with its own artefacts, stories, history and geography, roughly coexistent with this world (the ‘linear’ world) but not identical to it.

The central space for exploring Kymaerican history and heritage is online, but it erupts into the ‘linear’ world here and there. There is a permanent installation in Paris, Illinois; there are now five plaques in the UK: during the London exhibition there was a bus tour around Kymaerican sites corresponding with Central London.

The creator of this Borghesian experience is Eames Demetrios, designer, writer, filmmaker and Kymaerica’s ‘geographer-at-large’. I was struck by the parallels between his work, and some aspects of alternate reality gaming (ARGing), which I’ve argued here recently represents the emergence of a new genre of genuinely Web-native fiction (see Ben’s post below about World Without Oil for recent if:book discussion of this form). Though Kymaerica is presented as a piece of art, and alternate reality gaming generally thinks of itself more as entertainment, they have much in common. And this provides some intriguing insights into how, when thinking about the relationships in storytelling between form and content, the nature of the Web requires a radical rethinking of what fiction is. So my apologies in advance for the way this first attempt to do just that has turned into a longish post.

Eames calls what he does ‘three-dimensional storytelling’. I want to call the genre of which I believe that Kymaerica and ARGs are both instances ‘multimedia storytelling’. ‘Storytelling’, as opposed to ‘fiction’, because the notion of fiction belongs with the print book and is arguably inseparable from a series of relatively recent conventions around suspension of disbelief. And genuinely ‘multimedia’ in the sense that it uses multiple delivery mechanisms online but is not confined to the Web – indeed, is most successful when it escapes its boundaries.

People have been telling stories since the first humans sat round a culture. Narratives are fundamental to how we make sense of our world. But the print industry is such that otherwise highly-educated publishers, writers and so on talk as if no-one knew anything about works of the imagination before the novel appeared, along with the category of ‘fiction’ and all the cognitive conventions that entails. Why is this?

The novel is one delivery mechanism for storytelling, that emerged under specific social and cultural conditions. The economic, cultural and social structures created by and creating the novel hold up the commodification of individual imaginations (the convention of ‘original’ work, the idea of ‘great’ authors and so on) as their ideological and idealised centrepiece. The novel was for a long time the crown jewel of the literate culture industry. But it remains only one way of telling stories. And part of its conventions derive from the nature of the book as physical object: boundedness, fixity, authorship.

Meanwhile, many of us live now in a networked, post-industrial era, where many of the things that seemed so certain to a Dickens or Trollope no longer seem as reliable. And, perhaps fittingly, we have a new delivery mechanism for content. But unlike the book, which is bounded, fixed, authored, the Web is boundless, mutable, multi-authored and deeply unreliable. So the conception of singly-authored ‘fiction’ may not work any more. Hence I prefer the term ‘storytelling’: it is older than ‘fiction’, and less complicit in the conceptual framework that produced the novel. And as Ben has just suggested, the Web in many ways recalls oral storytelling much more than modern conceptions of fiction.

I also want to be clear about what I mean by ‘multimedia’, as the word is often used in contexts that replicate much of the print era’s mindset and as such, at a fundamental, misunderstand something about the Web. On the basis of experiments in this form to date, Multimedia fiction’ evokes something digital but book-like: bounded, authored, fixed like a book, just with extra visual stimuli and maybe some superficially interactive bells and whistles. I have yet to come across a piece, in this sense, of ‘multimedia fiction’ that’s as compelling as a book.

But the Web isn’t a book. Its formal nature is radically different. It’s boundless, mutable, multi-authored. So if the concrete physical form and economic conditions of a book’s production make certain demands of a story, and reciprocally shape its reading public, then what equivalent demands do the Web make?

Gamer Theory and Mediacommons demonstrate the potential for a ‘networked book’ to become a site of conversation, networked debate and dynamic exploration. But these are discursive rather than imaginative works. If the generic markers of a novel are fairly recognisable, what are the equivalent markers of a networked story? Drawing out the parallels between Kymaerica and an ARG, I want to suggest a concept of ‘multimedia storytelling’ characterised by the following qualities:

1) fragmentation,

2) a rebalancing of authorship with collaboration, and

3) a dissolution of the boundary between fact and fiction, and attendant replacement of ‘suspension of disbelief’ with play.

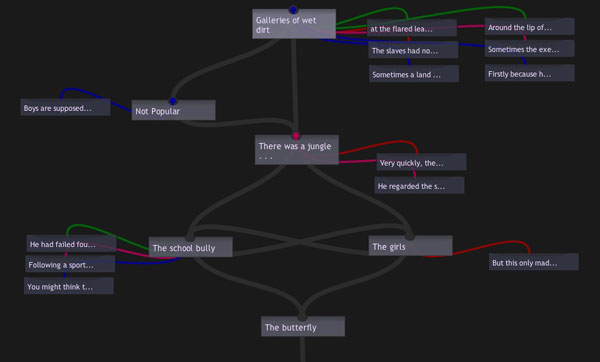

Web reading tends towards entropy. You go looking for statistics on the Bornean rainforest and find yourself reading the blog of someone who collects orang utan coffee mugs. Anyone doing sustained research on the Web needs a well-developed ability to navigate countless digressions, and derive coherence from the sea of chatter. And multimedia storytelling mimics this reading practice. The reader’s activity consists not in turning pages but in following clues, leads, associative echos and lateral leaps, and reconstructing sense from the fragments. It is pleasurable precisely because it offers a souped-up, pre-authored and more rewarding (because fantastic) version of the usual site-hopping experience. A typical ARG may include many different websites along with emails, IM chats, live action and other media. Part of the pleasure is derived from an experience that requires the ‘reader’ to sift through a fragmented body of information and reassemble the story.

Kymaerica is not fragmented across the Web like an ARG: the bulk of the story archive is available through the eponymous site. But the offline, physical traces of its story can be found in Texas, Illinois, London, Oxfordshire and elsewheres. And the story itself is deliberately fragmented. The way Eames explains it, he has the entire history of this world worked out in detail, but deliberately only reveals tiny parts of it through supposedly ‘factual’ tools such as plaques, guides and the kinds of snippet you might find in a museum dealing with the ‘real’ or factual world. “I always want to hint at something that’s just out of reach,” he told me. “It’s like writing a novel so you can publish a haiku.”

So just as an ARG offers fragments of the story for the players to reconstitute, for Eames it’s up to the audience to join the dots. This fragmented delivery then requires a radical rebalancing of the relationship between the author and the reader.

Whereas the relationship between a print author and a novel reader might be characterised as serial imaginative monogamy, the relationship between multimedia storytelling and its readers is fragmented, multiple, polyamorous, mutable. Again, this mimics the multiplicity, interactivity and mutability of Web reading, along with its greater reliance on user-generated content. ARG stories play out in time and, while the core story is worked out in advance, are highly improvisatory on the edges. Players work together on fora, or even – as in WWO – write additional imaginative content for the story. Interaction with characters in the story may take place in real time, either in the flesh or by IM or email; mistakes may generate whole new storylines; the players collaborate to solve puzzles and progress the story.

Eames’ three-dimensional storytelling remains similarly improvisatory. The back story is worked out ahead of schedule; but every conversation he has with others expands the story further, and needs to be incorporated into the archives. He’s keen to get the world well enough established to invite others to contribute material to the archives. And the experience is highly absorbing, even for the initially sceptical: in Paris, Illinois, the local townsfolk now hold a Kymaerican Spelling Bee as part of the town’s annual festival. Neither ARGs nor Kymaerica have entirely abandoned the notion of sustained authorship, as in different ways Ficlets or the Million Penguins wiki experiment attempt to do. Rather, it has been resituated in a context where the reader or listener has been recast as something more like a player. The story is a game; the game structure already exists; but the game is not there until it is played.

The replacement of ‘reading’ or ‘listening’ with ‘playing’ is the final characteristic I associate with multimedia storytelling, and is inseparable from the existence of Web stories in a network rather than a bounded artefact, whether print book or CD-ROM. A networked story is porous at the edges, inviting participation, comment and contribution; this renders the notion of ‘suspension of disbelief’ useless.

The first books represented a revered source of ancient authority: the Bible, the classical philosophers, the theologians. And even when telling stories, books provide a conceptual proscenium arch. Opening the covers of a book, like seeing the lights go down in a theatre, conveys a clear signal to begin your ‘suspension of disbelief’. But the Web gives no such clear signals. The Web is all that is not authoritative: it is a white noise of opinion, bias, speculation, argument and debate. Story, in essence. Even the facts on the Web are more like narratives than any reliable truth. The Web won’t tell you which sites you can take seriously and which not; there are no boundary markers between suspending disbelief and taking things literally. Instead of establishing clear conventions for which books are to be taken as ‘authoritative’ and read literally, and which to be treated as pure imagination, the Web invites the reader to half-believe everything all the time, and believe nothing at the same time. To play a game of ‘What if this were true’?

Again, multimedia storytelling mimics this experience. Is this site in-game, or just the product of some crazy people? Was there really a Great Dangaroo Flood on Old Compton St? It uses familiar tools conventionally used to communicate ‘real world’ information: email, IM, the semiotic register of tourist guides, plaques, visitors’ centres. It hands the responsibility for deciding on when to suspend disbelief back to the individual. And in doing so, it transforms this from ‘suspension of disbelief’ to an active choice: to a kind of performed imaginative participation best described as ‘play’.

Multimedia stories are not ‘read’: they are played. And unlike a suspension of disbelief, which contains within itself the assumption that we will afterwards revert to a condition of lucid rationality, play has a tendency to overspill its boundaries. The Parisian Embassy in Illinois is beginning to have a reciprocal effect on its surroundings: a street in the town has been renamed in line with Kymaerican history. The Florida authority responsible for historic sites has received at least one complaint about Kymaerican plaques, which they sensibly just said were not their responsibility. Take away the proscenium arch and fact and fiction begin dancing in ways that either exhilarate or terrify you.

Reports of the death of the novel are greatly exaggerated. Multimedia storytelling in the form I’ve just tried to outline does not compete with the novel, for reasons which I hope I’ve made clear. But the Web as storytelling medium deserves better than misguided attempts either to claim its ascendancy over previous forms, or else to force it to deliver against ideas of ‘fiction’ that do not reflect its nature. The interlocking qualities of fragmentation, collaboration and boundlessness mimic the experiences of reading on the Web and require a different kind of participation than ‘reading’. Suspension of disbelief becomes deliberately-performed play, collaborative reconstruction of the story is essential to the experience, and an ongoing improvisatory dance takes place between author and readership.