There’s an essay worth reading in the ny times book review this past sunday by Steven Johnson about a powerful semantic desktop management and search tool recently released for Macs.  The software (called DEVONthink) not only helps organize and briskly sift through readings, clippings, quotes, and one’s own past writings, but assists in the mysterious mental processes that are at the heart of writing – associative trains, useful non sequiturs, serendipitous stumbles. In effect, we now have a tool resembling the Memex device described in the seminal 1945 essay, As We May Think by visionary engineer Vannevar Bush. Working with the cutting edge technologies of his day – microfilm, thermionic tubes, and punch, or “Hollerith,” cards – Bush pondered how technology might help humanity to manage and make use of its vast systems of information. His recognition of the basic problem is no less relevant today: “Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing.” Fast forward to 2005. Now, the holy grail of search is the Semantic Web – moving beyond the artificiality of crude content-based queries and bringing meaning, relevance, and associations into the mix.

The software (called DEVONthink) not only helps organize and briskly sift through readings, clippings, quotes, and one’s own past writings, but assists in the mysterious mental processes that are at the heart of writing – associative trains, useful non sequiturs, serendipitous stumbles. In effect, we now have a tool resembling the Memex device described in the seminal 1945 essay, As We May Think by visionary engineer Vannevar Bush. Working with the cutting edge technologies of his day – microfilm, thermionic tubes, and punch, or “Hollerith,” cards – Bush pondered how technology might help humanity to manage and make use of its vast systems of information. His recognition of the basic problem is no less relevant today: “Our ineptitude in getting at the record is largely caused by the artificiality of systems of indexing.” Fast forward to 2005. Now, the holy grail of search is the Semantic Web – moving beyond the artificiality of crude content-based queries and bringing meaning, relevance, and associations into the mix.

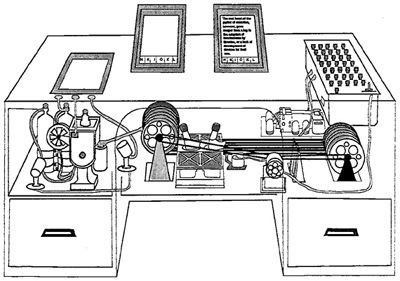

“Consider a future device for individual use, which is a sort of mechanized private file and library. It needs a name, and to coin one at random, “memex” will do. A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.” – Vannevar Bush

It’s quite suggestive that DEVONthink’s semantic search function can to an extent be trained, taking the obnoxious little puppy on Windows search toward its full potential – a sleek, truffle-tuned hound. When Johnson loads his body of work onto the computer, the hound picks up the distinctive scent of his writing, which in turn suggests affinities, similarities, and connections to other materials – truffles – that will find their way into later works.

Says Johnson on his latest

blog post, which goes into much greater detail than the Times piece:

“I have pre-filtered the results by selecting quotes that interest me, and by archiving my own prose. The signal-to-noise ratio is so high because I’ve eliminated 99% of the noise on my own.”

But it is significant that DEVONthink is not useful for searching entire books (the author’s own manuscripts notwithstanding). Currently, the tool is ideal for locating chunks of text that fall within the “sweet spot” of 50-500 words. If your archives include entire book-length texts, then the honing power is diminished. DEVONthink is optimal as a clip searcher. File searching remains a frustrating enterprise.

Johnson makes note of this:

“So the proper unit for this kind of exploratory, semantic search is not the file, but rather something else, something I don’t quite have a word for: a chunk or cluster of text, something close to those little quotes that I’ve assembled in DevonThink. If I have an eBook of Manual DeLanda’s on my hard drive, and I search for “urban ecosystem” I don’t want the software to tell me that an entire book is related to my query. I want the software to tell me that these five separate paragraphs from this book are relevant. Until the tools can break out those smaller units on their own, I’ll still be assembling my research library by hand in DevonThink.”

Another point (from the Times piece) worth highlighting here, which relates to our discussion of

the networked book:

“If these tools do get adopted, will they affect the kinds of books and essays people write? I suspect they might, because they are not as helpful to narratives or linear arguments; they’re associative tools ultimately. They don’t do cause-and-effect as well as they do ‘x reminds me of y.’ So they’re ideally suited for books organized around ideas rather than single narrative threads: more ‘Lives of a Cell’ and ‘The Tipping Point’ than ‘Seabiscuit.'”

And what about other forms of information – images, video, sound etc.? These media will come to play a larger role in the writing process, given the ease of processing them in a PC/web context. Images and music trump language in their associative power (a controversial assertion, please debate it!), and present us with layers of meaning that are harder to dissect, certainly by machine. It is an inchoate hound to be sure.

The software (called DEVONthink) not only helps organize and briskly sift through readings, clippings, quotes, and one’s own past writings, but assists in the mysterious mental processes that are at the heart of writing – associative trains, useful non sequiturs, serendipitous stumbles. In effect, we now have a tool resembling the

The software (called DEVONthink) not only helps organize and briskly sift through readings, clippings, quotes, and one’s own past writings, but assists in the mysterious mental processes that are at the heart of writing – associative trains, useful non sequiturs, serendipitous stumbles. In effect, we now have a tool resembling the

Says Johnson on his latest

Says Johnson on his latest  And what about other forms of information – images, video, sound etc.? These media will come to play a larger role in the writing process, given the ease of processing them in a PC/web context. Images and music trump language in their associative power (a controversial assertion, please debate it!), and present us with layers of meaning that are harder to dissect, certainly by machine. It is an inchoate hound to be sure.

And what about other forms of information – images, video, sound etc.? These media will come to play a larger role in the writing process, given the ease of processing them in a PC/web context. Images and music trump language in their associative power (a controversial assertion, please debate it!), and present us with layers of meaning that are harder to dissect, certainly by machine. It is an inchoate hound to be sure.

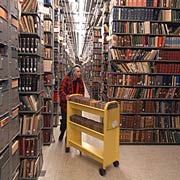

The recent buzz surrounding Google’s library intitiative has everyone talking about the future of research, which inevitably raises the question: how will the digitization of library collections change the role of the librarian? I would guess that, far from becoming obsolete, their role will in fact be elevated in importance, if not necessarily in status. They could very well come to be our indispensible guides through the labyrinth – if perhaps invisible, engineering behind the digital walls.

The recent buzz surrounding Google’s library intitiative has everyone talking about the future of research, which inevitably raises the question: how will the digitization of library collections change the role of the librarian? I would guess that, far from becoming obsolete, their role will in fact be elevated in importance, if not necessarily in status. They could very well come to be our indispensible guides through the labyrinth – if perhaps invisible, engineering behind the digital walls.