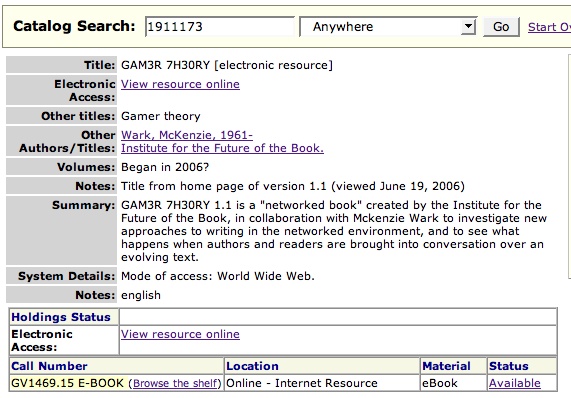

Here’s a wonderful thing I stumbled across the other day: GAM3R 7H30RY has its very own listing in North Carolina State University’s online library catalog.

The catalog is worth browsing in general. Since January, it’s been powered by Endeca, a fantastic library search tool that, among many other things, preserves some of the serendipity of physical browsing by letting you search the shelves around your title.

(Thanks, Monica McCormick!)

Category Archives: search

“a duopoly of Reuters-AP”: illusions of diversity in online news

Newswatch reports a powerful new study by the University of Ulster Centre for Media Research that confirms what many of us have long suspected about online news sources:

Through an examination of the content of major web news providers, our study confirms what many web surfers will already know – that when looking for reporting of international affairs online, we see the same few stories over and over again. We are being offered an illusion of information diversity and an apparently endless range of perspectives which in fact what is actually being offered is very limited information.

The appearance of diversity can be a powerful thing. Back in March, 2004, the McClatchy Washington Bureau (then Knight Ridder) put out a devastating piece revealing how the Iraqi National Congress (Ahmad Chalabi’s group) had fed dubious intelligence on Iraq’s WMDs not only to the Bush administration (as we all know), but to dozens of news agencies. The effect was a swarm of seemingly independent yet mutually corroborating reportage, edging American public opinion toward war.

A June 26, 2002, letter from the Iraqi National Congress to the Senate Appropriations Committee listed 108 articles based on information provided by the INC’s Information Collection Program, a U.S.-funded effort to collect intelligence in Iraq.

The assertions in the articles reinforced President Bush’s claims that Saddam Hussein should be ousted because he was in league with Osama bin Laden, was developing nuclear weapons and was hiding biological and chemical weapons.

Feeding the information to the news media, as well as to selected administration officials and members of Congress, helped foster an impression that there were multiple sources of intelligence on Iraq’s illicit weapons programs and links to bin Laden.

In fact, many of the allegations came from the same half-dozen defectors, weren’t confirmed by other intelligence and were hotly disputed by intelligence professionals at the CIA, the Defense Department and the State Department.

Nevertheless, U.S. officials and others who supported a pre-emptive invasion quoted the allegations in statements and interviews without running afoul of restrictions on classified information or doubts about the defectors’ reliability.

Other Iraqi groups made similar allegations about Iraq’s links to terrorism and hidden weapons that also found their way into official administration statements and into news reports, including several by Knight Ridder.

The repackaging of information goes into overdrive with the internet, and everyone, from the lone blogger to the mega news conglomerate, plays a part. Moreover, it’s in the interest of the aggregators and portals like Google and MSN to emphasize cosmetic or brand differences, so as to bolster their claims as indispensible filters for a tidal wave of news. So whether it’s Bush-Cheney-Chalabi’s WMDs or Google News’s “4,500 news sources updated continuously,” we need to maintain a skeptical eye.

***Related: myths of diversity in book publishing and large-scale digitization efforts.

google flirts with image tagging

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

I played a few rounds but quickly grew tired of the bland consensus that the game encourages. Matches tend to be banal, basic descriptors, while anything tricky usually results in a pass. In other words, all the pleasure of folksonomies — splicing one’s own idiosyncratic sense of things with the usually staid task of classification — is removed here. I don’t see why they don’t open the database up to much broader tagging. Integrate it with the image search and harvest a bigger crop of metadata.

Right now, it’s more like Tom Sawyer tricking the other boys into whitewashing the fence. Only, I don’t think many will fall for this one because there’s no real incentive to participation beyond a halfhearted points system. For every matched tag, you and your partner score points, which accumulate in your Google account the more you play. As far as I can tell, though, points don’t actually earn you anything apart from a shot at ranking in the top five labelers, which Google lists at the end of each game. Whitewash, anyone?

In some ways, this reminded me of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an “artificial artificial intelligence” service where anyone can take a stab at various HIT’s (human intelligence tasks) that other users have posted. Tasks include anything from checking business hours on restaurant web sites against info in an online directory, to transcribing podcasts (there are a lot of these). “Typically these tasks are extraordinarily difficult for computers, but simple for humans to answer,” the site explains. In contrast to the Google image game, with the Mechanical Turk, you can actually get paid. Fees per HIT range from a single penny to several dollars.

I’m curious to see whether Google goes further with tagging. Flickr has fostered the creation of a sprawling user-generated taxonomy for its millions of images, but the incentives to tagging there are strong and inextricably tied to users’ personal investment in the production and sharing of images, and the building of community. Amazon, for its part, throws money into the mix, which (however modest the sums at stake) makes Mechanical Turk an intriguing, and possibly entertaining, business experiment, not to mention a place to make a few extra bucks. Google’s experiment offers neither, so it’s not clear to me why people should invest.

showtiming our libraries

Google’s contract with the University of California to digitize library holdings was made public today after pressure from The Chronicle of Higher Education and others. The Chronicle discusses some of the key points in the agreement, including the astonishing fact that Google plans to scan as many as 3,000 titles per day, and its commitment, at UC’s insistence, to always make public domain texts freely and wholly available through its web services.

Google’s contract with the University of California to digitize library holdings was made public today after pressure from The Chronicle of Higher Education and others. The Chronicle discusses some of the key points in the agreement, including the astonishing fact that Google plans to scan as many as 3,000 titles per day, and its commitment, at UC’s insistence, to always make public domain texts freely and wholly available through its web services.

But there are darker revelations as well, and Jeff Ubois, a TV-film archivist and research associate at Berkeley’s School of Information Management and Systems, hones in on some of these on his blog. Around the time that the Google-UC deal was first announced, Ubois compared it to Showtime’s now-infamous compact with the Smithsonian, which caused a ripple of outrage this past April. That deal, the details of which are secret, basically gives Showtime exclusive access to the Smithsonian’s film and video archive for the next 30 years.

The parallels to the Google library project are many. Four of the six partner libraries, like the Smithsonian, are publicly funded institutions. And all the agreements, with the exception of U. Michigan, and now UC, are non-disclosure. Brewster Kahle, leader of the rival Open Content Alliance, put the problem clearly and succinctly in a quote in today’s Chronicle piece:

We want a public library system in the digital age, but what we are getting is a private library system controlled by a single corporation.

He was referring specifically to sections of this latest contract that greatly limit UC’s use of Google copies and would bar them from pooling them in cooperative library systems. I vocalized these concerns rather forcefully in my post yesterday, and may have gotten a couple of details wrong, or slightly overstated the point about librarians ceding their authority to Google’s algorithms (some of the pushback in comments and on other blogs has been very helpful). But the basic points still stand, and the revelations today from the UC contract serve to underscore that. This ought to galvanize librarians, educators and the general public to ask tougher questions about what Google and its partners are doing. Of course, all these points could be rendered moot by one or two bad decisions from the courts.

librarians, hold google accountable

I’m quite disappointed by this op-ed on Google’s library intiative in Tuesday’s Washington Post. It comes from Richard Ekman, president of the Council of Independent Colleges, which represents 570 independent colleges and universities in the US (and a few abroad). Generally, these are mid-tier schools — not the elite powerhouses Google has partnered with in its digitization efforts — and so, being neither a publisher, nor a direct representative of one of the cooperating libraries, I expected Ekman might take a more measured approach to this issue, which usually elicits either ecstatic support or vociferous opposition. Alas, no.

To the opposition, namely, the publishing industry, Ekman offers the usual rationale: Google, by digitizing the collections of six of the english-speaking world’s leading libraries (and, presumably, more are to follow) is doing humanity a great service, while still fundamentally respecting copyrights — so let’s not stand in its way. With Google, however, and with his own peers in education, he is less exacting.

The nation’s colleges and universities should support Google’s controversial project to digitize great libraries and offer books online. It has the potential to do a lot of good for higher education in this country.

Now, I’ve poked around a bit and located the agreement between Google and the U. of Michigan (freely available online), which affords a keyhole view onto these grand bargains. Basically, Google makes scans of U. of M.’s books, giving them images and optical character recognition files (the texts gleaned from the scans) for use within their library system, keeping the same for its own web services. In other words, both sides get a copy, both sides win.

If you’re not Michigan or Google, though, the benefits are less clear. Sure, it’s great that books now come up in web searches, and there’s plenty of good browsing to be done (and the public domain texts, available in full, are a real asset). But we’re in trouble if this is the research tool that is to replace, by force of market and by force of users’ habits, online library catalogues. That’s because no sane librarian would outsource their profession to an unaccountable private entity that refuses to disclose the workings of its system — in other words, how does Google’s book algorithm work, how are the search results ranked? And yet so many librarians are behind this plan. Am I to conclude that they’ve all gone insane? Or are they just so anxious about the pace of technological change, driven to distraction by fears of obsolescence and diminishing reach, that they are willing to throw their support uncritically behind the company, who, like a frontier huckster, promises miracle cures and grand visions of universal knowledge?

We may be resigned to the steady takeover of college bookstores around the country by Barnes and Noble, but how do we feel about a Barnes and Noble-like entity taking over our library systems? Because that is essentially what is happening. We ought to consider the Google library pact as the latest chapter in a recent history of consolidation and conglomeratization in publishing, which, for the past few decades (probably longer, I need to look into this further) has been creeping insidiously into our institutions of higher learning. When Google struck its latest deal with the University of California, and its more than 100 libraries, it made headlines in the technology and education sections of newspapers, but it might just as well have appeared in the business pages under mergers and acquisitions.

So what? you say. Why shouldn’t leaders in technology and education seek each other out and forge mutually beneficial relationships, relationships that might yield substantial benefits for large numbers of people? Okay. But we have to consider how these deals among titans will remap the information landscape for the rest of us. There is a prevailing attitude today, evidenced by the simplistic public debate around this issue, that one must accept technological advances on the terms set by those making the advances. To question Google (and its collaborators) means being labeled reactionary, a dinosaur, or technophobic. But this is silly. Criticizing Google does not mean I am against digital libraries. To the contrary, I am wholeheartedly in favor of digital libraries, just the right kind of digital libraries.

What good is Google’s project if it does little more than enhance the world’s elite libraries and give Google the competitive edge in the search wars (not to mention positioning them in future ebook and print-on-demand markets)? Not just our little institute, but larger interest groups like the CIC ought to be voices of caution and moderation, celebrating these technological breakthroughs, but at the same time demanding that Google Book Search be more than a cushy quid pro quo between the powerful, with trickle-down benefits that are dubious at best. They should demand commitments from the big libraries to spread the digital wealth through cooperative web services, and from Google to abide by certain standards in its own web services, so that smaller librarians in smaller ponds (and the users they represent) can trust these fantastic and seductive new resources. But Ekman, who represents 570 of these smaller ponds, doesn’t raise any of these questions. He just joins the chorus of approval.

What’s frustrating is that the partner libraries themselves are in the best position to make demands. After all, they have the books that Google wants, so they could easily set more stringent guidelines for how these resources are to be redeployed. But why should they be so magnanimous? Why should they demand that the wealth be shared among all institutions? If every student can access Harvard’s books with the click of a mouse, than what makes Harvard Harvard? Or Stanford Stanford?

Enlightened self-interest goes only so far. And so I repeat, that’s why people like Ekman, and organizations like the CIC, should be applying pressure to the Harvards and Stanfords, as should organizations like the Digital Library Federation, which the Michigan-Google contract mentions as a possible beneficiary, through “cooperative web services,” of the Google scanning. As stipulated in that section (4.4.2), however, any sharing with the DLF is left to Michigan’s “sole discretion.” Here, then, is a pressure point! And I’m sure there are others that a more skilled reader of such documents could locate. But a quick Google search (acceptable levels of irony) of “Digital Library Federation AND Google” yields nothing that even hints at any negotiations to this effect. Please, someone set me straight, I would love to be proved wrong.

Google, a private company, is in the process of annexing a major province of public knowledge, and we are allowing it to do so unchallenged. To call the publishers’ legal challenge a real challenge, is to misidentify what really is at stake. Years from now, when Google, or something like it, exerts unimaginable influence over every aspect of our informated lives, we might look back on these skirmishes as the fatal turning point. So that’s why I turn to the librarians. Raise a ruckus.

UPDATE (8/25): The University of California-Google contract has just been released. See my post on this.

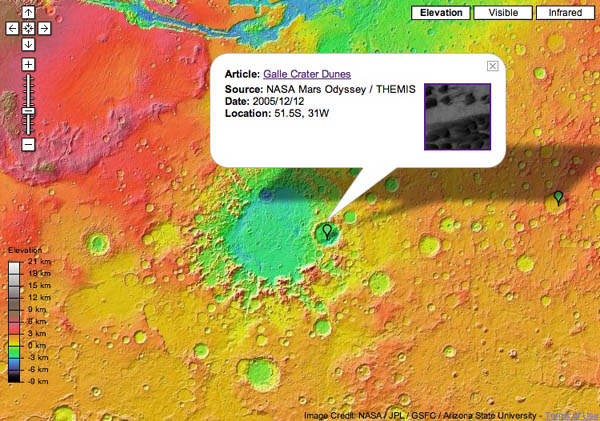

google on mars

Apparently, this came out in March, but I ‘ve only just stumbled on it now. Google has a version of its maps program for the planet Mars, or at least the part of if explored and documented by the 2001 NASA Mars Odyssey mission. It’s quite spectacular, especially the psychedelic elevation view:

There’s also various info tied to specific coordinates on the map: location of dunes, craters, planes etc., as well as stories from the Odyssey mission, mostly descriptions of the Martian landscape. It would be fun to do an anthology of Mars-located science fiction with the table of contents mapped, or an edition of Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles. Though I suppose there’d a fair bit of retrofitting of the atlas to tales written out of pure fancy and not much knowledge of Martian geography (Marsography?). If nothing else, there’s the seeds of a great textbook here. Does the Google Maps API extend to Mars, or is it just an earth thing?

u.c. offers up stacks to google

Less than two months after reaching a deal with Microsoft, the University of California has agreed to let Google scan its vast holdings (over 34 million volumes) into the Book Search database. Google will undoubtedly dig deeper into the holdings of the ten-campus system’s 100-plus libraries than Microsoft, which is a member of the more copyright-cautious Open Content Alliance, and will focus primarily on books unambiguously in the public domain. The Google-UC alliance comes as major lawsuits against Google from the Authors Guild and Association of American Publishers are still in the evidence-gathering phase.

Meanwhile, across the drink, French publishing group La Martiniè re in June brought suit against Google for “counterfeiting and breach of intellectual property rights.” Pretty much the same claim as the American industry plaintiffs. Later that month, however, German publishing conglomerate WBG dropped a petition for a preliminary injunction against Google after a Hamburg court told them that they probably wouldn’t win. So what might the future hold? The European crystal ball is murky at best.

During this period of uncertainty, the OCA seems content to let Google be the legal lightning rod. If Google prevails, however, Microsoft and Yahoo will have a lot of catching up to do in stocking their book databases. But the two efforts may not be in such close competition as it would initially seem.

Google’s library initiative is an extremely bold commercial gambit. If it wins its cases, it stands to make a great deal of money, even after the tens of millions it is spending on the scanning and indexing the billions of pages, off a tiny commodity: the text snippet. But far from being the seed of a new literary remix culture, as Kevin Kelly would have us believe (and John Updike would have us lament), the snippet is simply an advertising hook for a vast ad network. Google’s not the Library of Babel, it’s the most sublimely sophisticated advertising company the world has ever seen (see this funny reflection on “snippet-dangling”). The OCA, on the other hand, is aimed at creating a legitimate online library, where books are not a means for profit, but an end in themselves.

Brewster Kahle, the founder and leader of the OCA, has a rather immodest aim: “to build the great library.” “That was the goal I set for myself 25 years ago,” he told The San Francisco Chronicle in a profile last year. “It is now technically possible to live up to the dream of the Library of Alexandria.”

So while Google’s venture may be more daring, more outrageous, more exhaustive, more — you name it –, the OCA may, in its slow, cautious, more idealistic way, be building the foundations of something far more important and useful. Plus, Kahle’s got the Bookmobile. How can you not love the Bookmobile?

the myth of universal knowledge 2: hyper-nodes and one-way flows

My post a couple of weeks ago about Jean-Noël Jeanneney’s soon-to-be-released anti-Google polemic sparked a discussion here about the cultural trade deficit and the linguistic diversity (or lack thereof) of digital collections. Around that time, Rüdiger Wischenbart, a German journalist/consultant, made some insightful observations on precisely this issue in an inaugural address to the 2006 International Conference on the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage in Salzburg. His discussion is framed provocatively in terms of information flow, painting a picture of a kind of fluid dynamics of global culture, in which volume and directionality are the key indicators of power.

My post a couple of weeks ago about Jean-Noël Jeanneney’s soon-to-be-released anti-Google polemic sparked a discussion here about the cultural trade deficit and the linguistic diversity (or lack thereof) of digital collections. Around that time, Rüdiger Wischenbart, a German journalist/consultant, made some insightful observations on precisely this issue in an inaugural address to the 2006 International Conference on the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage in Salzburg. His discussion is framed provocatively in terms of information flow, painting a picture of a kind of fluid dynamics of global culture, in which volume and directionality are the key indicators of power.

First, he takes us on a quick tour of the print book trade, pointing out the various roadblocks and one-way streets that skew the global mind map. A cursory analysis reveals, not surprisingly, that the international publishing industry is locked in a one-way flow maximally favoring the West, and, moreover, that present digitization efforts, far from ushering in a utopia of cultural equality, are on track to replicate this.

…the market for knowledge is substantially controlled by the G7 nations, that is to say, the large economic powers (the USA, Canada, the larger European nations and Japan), while the rest of the world plays a subordinate role as purchaser.

Foreign language translation is the most obvious arena in which to observe the imbalance. We find that the translation of literature flows disproportionately downhill from Anglophone heights — the further from the peak, the harder it is for knowledge to climb out of its local niche. Wischenbart:

An already somewhat obsolete UNESCO statistic, one drawn from its World Culture Report of 2002, reckons that around one half of all translated books worldwide are based on English-language originals. And a recent assessment for France, which covers the year 2005, shows that 58 percent of all translations are from English originals. Traditionally, German and French originals account for an additional one quarter of the total. Yet only 3 percent of all translations, conversely, are from other languages into English.

…When it comes to book publishing, in short, the transfer of cultural knowledge consists of a network of one-way streets, detours, and barred routes.

…The central problem in this context is not the purported Americanization of knowledge or culture, but instead the vertical cascade of knowledge flows and cultural exports, characterized by a clear power hierarchy dominated by larger units in relation to smaller subordinated ones, as well as a scarcity of lateral connections.

Turning his attention to the digital landscape, Wischenbart sees the potential for “new forms of knowledge power,” but quickly sobers us up with a look at the way decentralized networks often still tend toward consolidation:

Previously, of course, large numbers of books have been accessible in large libraries, with older books imposing their contexts on each new release. The network of contents encompassing book knowledge is as old as the book itself. But direct access to the enormous and constantly growing abundance of information and contents via the new information and communication technologies shapes new knowledge landscapes and even allows new forms of knowledge power to emerge.

Theorists of networks like Albert-Laszlo Barabasi have demonstrated impressively how nodes of information do not form a balanced, level field. The more strongly they are linked, the more they tend to constitute just a few outstandingly prominent nodes where a substantial portion of the total information flow is bundled together. The result is the radical antithesis of visions of an egalitarian cyberspace.

He then trains his sights on the “long tail,” that egalitarian business meme propogated by Chris Anderson’s new book, which posits that the new information economy will be as kind, if not kinder, to small niche markets as to big blockbusters. Wischenbart is not so sure:

He then trains his sights on the “long tail,” that egalitarian business meme propogated by Chris Anderson’s new book, which posits that the new information economy will be as kind, if not kinder, to small niche markets as to big blockbusters. Wischenbart is not so sure:

…there exists a massive problem in both the structure and economics of cultural linkage and transfer, in the cultural networks existing beyond the powerful nodes, beyond the high peaks of the bestseller lists. To be sure, the diversity found below the elongated, flattened curve does constitute, in the aggregate, approximately one half of the total market. But despite this, individual authors, niche publishing houses, translators and intermediaries are barely compensated for their services. Of course, these multifarious works are produced, and they are sought out and consumed by their respective publics. But the “long tail” fails to gain a foothold in the economy of cultural markets, only to become – as in the 18th century – the province of the amateur. Such is the danger when our attention is drawn exclusively to dominant productions, and away from the less surveyable domains of cultural and knowledge associations.

John Cassidy states it more tidily in the latest New Yorker:

There’s another blind spot in Anderson’s analysis. The long tail has meant that online commerce is being dominated by just a few businesses — mega-sites that can house those long tails. Even as Anderson speaks of plentitude and proliferation, you’ll notice that he keeps returning for his examples to a handful of sites — iTunes, eBay, Amazon, Netflix, MySpace. The successful long-tail aggregators can pretty much be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Many have lamented the shift in publishing toward mega-conglomerates, homogenization and an unfortunate infatuation with blockbusters. Many among the lamenters look to the Internet, and hopeful paradigms like the long tail, to shake things back into diversity. But are the publishing conglomerates of the 20th century simply being replaced by the new Internet hyper-nodes of the 21st? Does Google open up more “lateral connections” than Bertelsmann, or does it simply re-aggregate and propogate the existing inequities? Wischenbart suspects the latter, and cautions those like Jeanneney who would seek to compete in the same mode:

If, when breaking into the digital knowledge society, European initiatives (for instance regarding the digitalization of books) develop positions designed to counteract the hegemonic status of a small number of monopolistic protagonists, then it cannot possibly suffice to set a corresponding European pendant alongside existing “hyper nodes” such as Amazon and Google. We have seen this already quite clearly with reference to the publishing market: the fact that so many globally leading houses are solidly based in Europe does nothing to correct the prevailing disequilibrium between cultures.

microsoft enlists big libraries but won’t push copyright envelope

In a significant challenge to Google, Microsoft has struck deals with the University of California (all ten campuses) and the University of Toronto to incorporate their vast library collections – nearly 50 million books in all – into Windows Live Book Search. However, a majority of these books won’t be eligible for inclusion in MS’s database. As a member of the decidedly cautious Open Content Alliance, Windows Live will restrict its scanning operations to books either clearly in the public domain or expressly submitted by publishers, leaving out the huge percentage of volumes in those libraries (if it’s at all like the Google five, we’re talking 75%) that are in copyright but out of print. Despite my deep reservations about Google’s ascendancy, they deserve credit for taking a much bolder stand on fair use, working to repair a major market failure by rescuing works from copyright purgatory. Although uploading libraries into a commercial search enclosure is an ambiguous sort of rescue.

smarter links for a better wikipedia

As Wikipedia continues its evolution, smaller and smaller pieces of its infrastructure come up for improvement. The latest piece to step forward to undergo enhancement: the link. “Computer scientists at the University of Karlsruhe in Germany have developed modifications to Wikipedia’s underlying software that would let editors add extra meaning to the links between pages of the encyclopaedia.” (full article) While this particular idea isn’t totally new (at least one previous attempt has been made: platypuswiki), SemanticWiki is using a high profile digital celebrity, which brings media attention and momentum.

What’s happening here is that under the Wikipedia skin, the SemanticWiki uses an extra bit of syntax in the link markup to inject machine readable information. A normal link in wikipedia is coded like this [link to a wiki page] or [http://www.someothersite.com link to an outside page]. What more do you need? Well, if by “you” I mean humans, the answer is: not much. We can gather context from the surrounding text. But our computers get left out in the cold. They aren’t smart enough to understand the context of a link well enough to make semantic decisions with the form “this link is related to this page this way”. Even among search engine algorithms, where PageRank rules them all, PageRank counts all links as votes, which increase the linked page’s value. Even PageRank isn’t bright enough to understand that you might link to something to refute or denigrate its value. When we write, we rely on judgement by human readers to make sense of a link’s context and purpose. The researchers at Karlsruhe, on the other hand, are enabling machine comprehension by inserting that contextual meaning directly into the links.

SemanticWiki links look just like Wikipedia links, only slightly longer. They include info like

- categories: An article on Karlsruhe, a city in Germany, could be placed in the City Category by adding

[[Category: City]]to the page. - More significantly, you can add typed relationships.

Karlsruhe [[:is located in::Germany]]would show up as Karlsruhe is located in Germany (the : before is located in saves typing). Other examples: in the Washington D.C. article, you can add [[is capital of:: United States of America]]. The types of relationships (“is capital of”) can proliferate endlessly. - attributes, which specify simple properties related to the content of an article without creating a link to a new article. For example,

[[population:=3,396,990]]

Adding semantic information to links is a good idea, and hewing closely to the current Wikipedia syntax is a smart tactic. But here’s why I’m not more optimistic: this solution combines the messiness of tagging with the bother of writing machine readable syntax. This combo reminds me of a great Simpsons quote, where Homer says, “Nuts and gum, together at last!” Tagging and semantic are not complementary functions – tagging was invented to put humans first, to relieve our fuzzy brains from the mechanical strictures of machine readable categorization; writing relationships in a machine readable format puts the machine squarely in front. It requires the proliferation of wikipedia type articles to explain each of the typed relationships and property names, which can quickly become unmaintainable by humans, exacerbating the very problem it’s trying to solve.

But perhaps I am underestimating the power of the network. Maybe the dedication of the Wikipedia community can overcome those intractible systemic problems. Through the quiet work of the gardeners who sleeplessly tend their alphanumeric plots, the fact-checkers and passers-by, maybe the SemanticWiki will sprout links with both human and computer sensible meanings. It’s feasible that the size of the network will self-generate consensus on the typology and terminology for links. And it’s likely that if Wikipedia does it, it won’t be long before semantic linking makes its way into the rest of the web in some fashion. If this is a success, I can foresee the semantic web becoming a reality, finally bursting forth from the SemanticWiki seed.

UPDATE:

I left off the part about how humans benefit from SemanticWiki type links. Obviously this better be good for something other than bringing our computers up to a second grade reading level. It should enable computers to do what they do best: sort through massive piles of information in milliseconds.

How can I search, using semantic annotations? – It is possible to search for the entered information in two differnt ways. On the one hand, one can enter inline queries in articles. The results of these queries are then inserted into the article instead of the query. On the other hand, one can use a basic search form, which also allows you to do some nice things, such as picture search and basic wildcard search.

For example, if I wanted to write an article on Acting in Boston, I might want a list of all the actors who were born in Boston. How would I do this now? I would count on the network to maintain a list of Bostonian thespians. But with SemanticWiki I can just add this: <ask>[[Category:Actor]] [[born in::Boston]], which will replace the inline query with the desired list of actors.

To do a more straightforward search I would go to the basic search page. If I had any questions about Berlin, I would enter it into the Subject field. SemanticWiki would return a list of short sentences where Berlin is the subject.

But this semantic functionality is limited to simple constructions and nouns—it is not well suited for concepts like 'politics,' or 'vacation'. One other point: SemanticWiki relationships are bounded by the size of the wiki. Yes, digital encyclopedias will eventually cover a wide range of human knowledge, but never all. In the end, SemanticWiki promises a digital network populated by better links, but it will take the cooperation of the vast human network to build it up.