This is the narrative text for an NEH Digital Humanities Start-UP grant we just applied for.

Narrative

With the advent of the cd-rom in the late 80s, a few pioneering humanities scholars began to develop a new vocabulary for multi-layered, multi-modal digital publications. Since that time, the internet has emerged as a powerful engine for collaboration across peer networks, radically collapsing the distance between authors and readers and creating new communal spaces for work and review.

To date, these two evolutionary streams have been largely separate. Rich multimedia is still largely consigned to individual consumption on the desktop, while networked collaboration generally occurs around predominantly textual media such as the blogosphere, or bite-sized fragments on YouTube and elsewhere. We propose to carry out initial planning for two ambitious digital publishing projects that will merge these streams into powerfully integrated experiences.

Although the locus of scholarly discourse is slowly but clearly moving from bound/printed pages to networked screens, we’ve yet to reach the tipping point. The printed book is still the gold standard of the academy. The goal of these projects is to produce born-digital works that are as elegant as printed books and also draw on the power of audio and video illustrations and new models of community-based inquiry -? and do all of these so well that they inspire a generation of young scholars with the promise of digital scholarship.

Robert Winter’s CD Companion Series (Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Mozart’s Dissonant Quartet, Dvorak’s New World Symphony) and the American Social History Project’s Who Built America? Volumes I and II were seminal works of multimedia scholarship and publishing. In their respective fields they were responsible for introducing and demonstrating the value of new media scholarship, as well as for setting a high standard for other work which followed.

Although these works were encoded on plastic cd-roms instead of on paper, they essentially followed the paradigm of print in the sense that they were page-based and very much the work of authors who took sole responsibility for the contents. The one obvious difference was the presence of audio and video illustrations on the page. This crucial advance allowed Robert Winter to provide a running commentary as readers listened to the music, or the Who Built America? authors to provide valuable supplementary materials and primary source documents such as William Jennings Bryan reading his famous “Cross of Gold” speech, or moving oral histories from the survivors of the Triangle Shirtwaist fire of 1911.

Since the release of these cd-roms, the internet and world wide web have come to the fore and upended the print-centric paradigm of reading as a solitary activity, moving it towards a more communal, networked model. As an example, three years ago my colleagues and I at the Institute for the Future of the Book began a series of “networked book” experiments to understand what happens when you locate a book in the dynamic social space of the Web. McKenzie Wark, a communication theorist and professor at The New School, had recently completed a draft of a serious theoretical work on video games. We put that book, Gamer Theory, online in a form adapted from conventional blog templates that allowed readers to post comments on individual paragraphs. While commenting on blogs is commonplace, readers’ comments invariably appear below the author’s text, usually hidden from sight in an endlessly scrolling field. Instead we put the reader’s comments directly to the right of Wark’s text, indicating that reader input would be an integral part of the whole. Within hours of the book’s “publication” on the web, page margins began to be populated with a lively back-and-forth among readers and with the author. As early reviewers said, it was no longer simply the author speaking, but rather the book itself, as the conversation in the margins became an intrinsic and important part of the whole.

The traditional top-down hierarchy of print, in which authors deliver wisdom from on high to receptive readers, was disrupted and replaced by a new model in which both authors and readers actively pursued knowledge and understanding. I’m not suggesting that our experiment caused this change, but rather that it has shed light on a process that is already well underway, helping to expose and emphasize the ways in which writing and reading are increasingly socially mediated activities.

Thanks to extraordinary recent advances, both technical and conceptual, we can imagine new multi-mediated forms of expression that leverage the web’s abundant resources more fully and are driven by networked communities of which readers and authors can work together to advance knowledge.

Let’s consider Who Built America?

In 1991, before going into production, we spent a full year in conversation with the book’s authors, Steve Brier and Josh Brown, mulling over the potential of an electronic edition. We realized that a history text is essentially a synthesis of the author’s interpretation and analysis of original source documents, and also of the works of other historians, as well as conversations in the scholarly community at large. We decided to make those layers more visible, taking advantage of the multimedia affordances and storage capacity of the cd-rom. We added hundreds of historical documents -? text, pictures, audio, video -? woven into dozens of “excursions” distributed throughout the text. These encouraged the student to dig deeper beneath encouraged them to interrogate the author’s conclusions and perhaps even come up with alternative analyses.

Re-imagining Who Built America? in the context of a dynamic network (rather than a frozen cd-rom), promises exciting new possibilities. Here are just a few:

• Access to source documents can be much more extensive and diverse, freed from the storage constraints of the cd-rom, as well as from many of the copyright clearance issues.

• Dynamic comment fields enable classes to produce their own unique editions. A discussion that began in the classroom can continue in the margins of the page, flowing seamlessly between school and home.

• The text continuously evolves, as authors add new findings and engage with readers who have begun to learn history by “doing” history, adding new research and alternative syntheses. Steve Brier tells a wonderful story about a high school class in a small town in central Ohio where the students and their teacher discovered some unknown letters from one of the earliest African-American trade union leaders in the late nineteenth century, making an important contribution to the historical record.

In short, we are re-imagining a history text as a networked, multi-layered learning environment in which authors and readers, teachers and students, work collaboratively.

Over the past months I’ve had several conversations with Brier and Brown about a completely new “networked” version of Who Built America?. They are excited about the possibility and have a good grasp of the challenges and potential. A good indication of this is Steve Brier’s comment: “If we’re going to expect readers to participate in these ways, we’re going to have to write in a whole new way.”

Discussions with Robert Winter have focused less on re-working the existing CD-Companions (which were monumental works) than on trying to figure out how to develop a template for a networked library of close readings of iconic musical compositions. The original CD-Companions existed as individual titles, isolated from one another. The promise of networked scholarship means that over time Winter and his readers will weave a rich tapestry of cross-links that map interconnections between different compositions, between different musical styles and techniques, and between music and other cultural forms. The original CD-Companions were done when computers had low-resolution black and white screens with extremely primitive audio capabilities and no video at all. High resolution color screens and sophisticated audio and video tools open up myriad possibilities for examining and contextualizing musical compositions. Particularly exciting is the prospect of harnessing Winter’s legendary charismatic teaching style via the creative, yet judicious use of video.

We are seeking a Level One Start-Up grant to hold a pair of two-day symposia, one devoted to each project. Each meeting will bring together approximately a dozen people -? the authors, designers, leading scholars from various related disciplines, and experts in building web-based communities around scholarly topics -? to brainstorm about how these projects might best be realized. We will publish the proceedings of these meetings online in such a way that interested parties can join the discussion and deepen our collective understanding. Finally, we will write a grant proposal to submit to foundations for funds to build out the projects in their entirety. The work described here will take place over a five-month period beginning September 2008 and ending February 2009.

Some of the questions to be addressed at the symposia are:

• what are new graphical and information design paradigms for orienting readers and enabling them to navigate within a multi-layered, multi-modal work?

• how do you distinguish between the reading space and the work space? how porous is the boundary between them?

• what do readers expect of authors in the context of a “networked” book?

• what new authorial skill sets need to be cultivated?

• what range of mechanisms for reader participation and author/reader interaction should we explore? (i.e. blog-style commenting, social filtering, rating mechanisms, annotation tools, social bookmarking/curating, personalized collection-building, tagging, etc.)

• how do readers become “trusted” within an open community? what are the social protocols required for a successful community-based project: terms of participation, quality control/vetting procedures, delegation of roles etc.

what does “community” mean in the context of a specific scholarly work?

• how will scholars and students cite the contents of dynamic, evolving works that are not “stable” like printed pages? how does the project get archived? how do you deal with versioning?

• if asynchronous online conversation becomes a powerful new mode of developing scholarship, how do we visualize these conversations and make them navigable, readable, and enjoyable?

Relevant websites

Video Demo for Who Built America? (circa 1993)

Video Demo for the Rite of Spring (circa 1990)

Introduction to the CD Companion to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (circa 1989)

Category Archives: scholarship

major news: IFB and NYU libraries to collaborate

A couple of weeks ago, I alluded to a new institutional partnership that’s been in the works for some time. Well I’m thrilled to officially announce that the we are joining forces with the NYU Division of Libraries!

From Carol A. Mandel, dean of the NYU Libraries. “IFB is a thought leader in the future of scholarly communication. We will work together to develop new software and new options that faculty can use to publish, review, share, and collaborate at NYU and in the larger academic community.”

Read the full press release: NYU Libraries & Institute for the Future of the Book Announce Partnership to Develop Tools for Digital Scholarly Research

A basic breakdown of what this means:

-? NYU is now our technical home. All IFB sites are running out of there with IT support from the NYU Libraries’ top-notch team.

-? Bob, Dan and I will serve as visiting scholars at NYU.

-? With recently secured NEH digital humanities start-up funding (along with other monies yet to be raised), we will work with the NYU digital library team, headed by James Bullen, to develop social networking tools and infrastructure for MediaCommons. This will serve as applied research for digital tools and frameworks that NYU is presently developing.

-? We will work with NYU librarians, with the digital library team, and with Monica McCormick, the Libraries’ program officer for digital scholarly publishing, to create forums for collaboration and to develop specific projects and digital initiatives with NYU faculty, and possibly NYU Press.

Needless to say, we’re tremendously excited about this partnership. Things are still being set up but expect more news in the weeks and months ahead.

MediaCommons paper up in commentable form

We’ve just put up a version of a talk Kathleen Fitzpatrick has been giving over the past few months describing the genesis of MediaCommons and its goals for reinventing the peer review process. The paper is in CommentPress — unfortunately not the new version, which we’re still working on (revised estimated release late April), it’s more or less the same build we used for the Iraq Study Group Report. The exciting thing here is that the form of the paper, constructed to solicit reader feedback directly alongside the text, actually enacts its content: radically transparent peer-to-peer review, scholars talking in the open, shepherding the development each other’s work. As of this writing there are already 21 comments posted in the page margins by members of the editorial board (fresh off of last weekend’s retreat) and one or two others. This is an important first step toward what will hopefully become a routine practice in the MediaCommons community.

In less than an hour, Kathleen will be delivering the talk, drawing on some of the comments, at this event at the University of Rochester. Kathleen also briefly introduced the paper yesterday on the MediaCommons blog and posed an interesting question that came out of the weekend’s discussion about whether we should actually be calling this group the “editorial board.” Some interesting discussion ensued. Also check at this: “A First Stab at Some General Principles”.

today at noon (e.s.t.)! online colloquy at chronicle of higher ed.

Bob will be appearing online at the Chronicle of Higher Education site for a live chat with readers about our recent cover story. The topic: “conversational scholarship.” 12 noon E.S.T.

UPDATE: you can now read a transcript of the chat here (same as the live link).

toward the establishment of an electronic press

A few months ago, Kathleen Fitzpatrick, a tenured professor of English and Media Studies at Pomona College, published an important statement at The Valve: On the Future of Academic Publishing, Peer Review, and Tenure Requirements. Not just another lament about the sorry state of scholarly publishing, Fitzpatrick’s piece is a manifesto calling for the creation of an electronic press whose goal is nothing less than establishing born-digital electronic scholarship as an equal to print.

A meeting we held in november with a group of leading academic bloggers raised many of the problems that people face trying to gain respect for online scholarship. Since that meeting we’ve been trying to understand what role the institute might play in changing the landscape. Reading and discussing Fitzpatrick’s manifesto catalyzed our thoughts.

We invited Kathleen to visit us in NY and proposed working with her to establish an electronic press that would be hosted by the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC (which is also the home of the Institute for the Future of the Book). Based on our preliminary discussions we think that the press should concentrate at first on work in the area of media studies. The projects themselves will take many different electronic forms – long, short; media-rich, text-only; linear, non-linear; etc. These projects will be subjected to strong peer-review, but we hope to develop a process that is tailored to the rhythms and structures of online publishing.

How might our conception of a press be updated for the networked age? How do we create a publishing ecology that supports discourse at all levels — from blog to working paper to monograph — focusing less on the products of scholarship and more on the process? In practical terms, how might this process make use of the linking, commenting, and versioning technologies developed by blogs and wikis in order to enrich the discrete and fixed scholarly text with an evolving, interactive network of discourse that encourages conversation, debate, reflection, and revision? How might peer review be reinvented as peer-to-peer review?

We’ve assembled a fantastic roster of over a dozen professors in english, media studies, film and the information sciences to gather for an ambitious one-day meeting in Los Angeles in late April at USC’s Annenberg Center for Communication to begin answering these questions. The goal is to survey the current landscape of scholarly publishing, to evaluate and learn from existing innovative efforts, and to begin talking seriously about the establishment in the very near future of a groundbreaking electronic press. Since this is quite a lot to cover in a single day, we’ve set up a blog to get the conversation going in advance. Kathleen currently has a terrific post laying out some of the first-order questions, which we expect to evolve through feedback into a concrete meeting agenda. Her original Valve essay is also there.

There’s still more than a month till folks gather in L.A., so in the meantime we’d like to invite anyone who’s interested to take part in the discussion on the blog and to help lay the groundwork for what we hope will be a very important meeting.

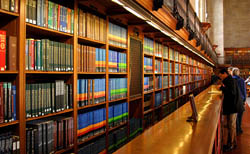

DRM and the damage done to libraries

A recent BBC article draws attention to widespread concerns among UK librarians (concerns I know are shared by librarians and educators on this side of the Atlantic) regarding the potentially disastrous impact of digital rights management on the long-term viability of electronic collections. At present, when downloads represent only a tiny fraction of most libraries’ circulation, DRM is more of a nuisance than a threat. At the New York Public library, for instance, only one “copy” of each downloadable ebook or audio book title can be “checked out” at a time — a frustrating policy that all but cancels out the value of its modest digital collection. But the implications further down the road, when an increasing portion of library holdings will be non-physical, are far more grave.

What these restrictions in effect do is place locks on books, journals and other publications — locks for which there are generally no keys. What happens, for example, when a work passes into the public domain but its code restrictions remain intact? Or when materials must be converted to newer formats but can’t be extracted from their original files? The question we must ask is: how can librarians, now or in the future, be expected to effectively manage, preserve and update their collections in such straightjacketed conditions?

This is another example of how the prevailing copyright fundamentalism threatens to constrict the flow and preservation of knowledge for future generations. I say “fundamentalism” because the current copyright regime in this country is radical and unprecedented in its scope, yet traces its roots back to the initially sound concept of limited intellectual property rights as an incentive to production, which, in turn, stemmed from the Enlightenment idea of an author’s natural rights. What was originally granted (hesitantly) as a temporary, statutory limitation on the public domain has spun out of control into a full-blown culture of intellectual control that chokes the flow of ideas through society — the very thing copyright was supposed to promote in the first place.

If we don’t come to our senses, we seem destined for a new dark age where every utterance must be sanctioned by some rights holder or licensing agent. Free thought isn’t possible, after all, when every thought is taxed. In his “An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?” Kant condemns as criminal any contract that compromises the potential of future generations to advance their knowledge. He’s talking about the church, but this can just as easily be applied to the information monopolists of our times and their new tool, DRM, which, in its insidious way, is a kind of contract (though one that is by definition non-negotiable since enforced by a machine):

But would a society of pastors, perhaps a church assembly or venerable presbytery (as those among the Dutch call themselves), not be justified in binding itself by oath to a certain unalterable symbol in order to secure a constant guardianship over each of its members and through them over the people, and this for all time: I say that this is wholly impossible. Such a contract, whose intention is to preclude forever all further enlightenment of the human race, is absolutely null and void, even if it should be ratified by the supreme power, by parliaments, and by the most solemn peace treaties. One age cannot bind itself, and thus conspire, to place a succeeding one in a condition whereby it would be impossible for the later age to expand its knowledge (particularly where it is so very important), to rid itself of errors, and generally to increase its enlightenment. That would be a crime against human nature, whose essential destiny lies precisely in such progress; subsequent generations are thus completely justified in dismissing such agreements as unauthorized and criminal.

We can only hope that subsequent generations prove more enlightened than those presently in charge.

what I heard at MIT

Over the next few days I’ll be sifting through notes, links, and assorted epiphanies crumpled up in my pocket from two packed, and at times profound, days at the Economics of Open Content symposium, hosted in Cambridge, MA by Intelligent Television and MIT Open CourseWare. For now, here are some initial impressions — things I heard, both spoken in the room and ricocheting inside my head during and since. An oral history of the conference? Not exactly. More an attempt to jog the memory. Hopefully, though, something coherent will come across. I’ll pick up some of these threads in greater detail over the next few days. I should add that this post owes a substantial debt in form to Eliot Weinberger’s “What I Heard in Iraq” series (here and here).

![]()

Naturally, I heard a lot about “open content.”

I heard that there are two kinds of “open.” Open as in open access — to knowledge, archives, medical information etc. (like Public Library of Science or Project Gutenberg). And open as in open process — work that is out in the open, open to input, even open-ended (like Linux, Wikipedia or our experiment with MItch Stephens, Without Gods).

I heard that “content” is actually a demeaning term, treating works of authorship as filler for slots — a commodity as opposed to a public good.

I heard that open content is not necessarily the same as free content. Both can be part of a business model, but the defining difference is control — open content is often still controlled content.

I heard that for “open” to win real user investment that will feedback innovation and even result in profit, it has to be really open, not sort of open. Otherwise “open” will always be a burden.

I heard that if you build the open-access resources and demonstrate their value, the money will come later.

I heard that content should be given away for free and that the money is to be made talking about the content.

I heard that reputation and an audience are the most valuable currency anyway.

I heard that the academy’s core mission — education, research and public service — makes it a moral imperative to have all scholarly knowledge fully accessible to the public.

I heard that if knowledge is not made widely available and usable then its status as knowledge is in question.

I heard that libraries may become the digital publishing centers of tomorrow through simple, open-access platforms, overhauling the print journal system and redefining how scholarship is disseminated throughout the world.

![]()

And I heard a lot about copyright…

I heard that probably about 50% of the production budget of an average documentary film goes toward rights clearances.

I heard that many of those clearances are for “underlying” rights to third-party materials appearing in the background or reproduced within reproduced footage. I heard that these are often things like incidental images, video or sound; or corporate logos or facades of buildings that happen to be caught on film.

I heard that there is basically no “fair use” space carved out for visual and aural media.

I heard that this all but paralyzes our ability as a culture to fully examine ourselves in terms of the media that surround us.

I heard that the various alternative copyright movements are not necessarily all pulling in the same direction.

I heard that there is an “inter-operability” problem between alternative licensing schemes — that, for instance, Wikipedia’s GNU Free Documentation License is not inter-operable with any Creative Commons licenses.

I heard that since the mass market content industries have such tremendous influence on policy, that a significant extension of existing copyright laws (in the United States, at least) is likely in the near future.

I heard one person go so far as to call this a “totalitarian” intellectual property regime — a police state for content.

I heard that one possible benefit of this extension would be a general improvement of internet content distribution, and possibly greater freedom for creators to independently sell their work since they would have greater control over the flow of digital copies and be less reliant on infrastructure that today only big companies can provide.

I heard that another possible benefit of such control would be price discrimination — i.e. a graduated pricing scale for content varying according to the means of individual consumers, which could result in fairer prices. Basically, a graduated cultural consumption tax imposed by media conglomerates

I heard, however, that such a system would be possible only through a substantial invasion of users’ privacy: tracking users’ consumption patterns in other markets (right down to their local grocery store), pinpointing of users’ geographical location and analysis of their socioeconomic status.

I heard that this degree of control could be achieved only through persistent surveillance of the flow of content through codes and controls embedded in files, software and hardware.

I heard that such a wholesale compromise on privacy is all but inevitable — is in fact already happening.

I heard that in an “information economy,” user data is a major asset of companies — an asset that, like financial or physical property assets, can be liquidated, traded or sold to other companies in the event of bankruptcy, merger or acquisition.

I heard that within such an over-extended (and personally intrusive) copyright system, there would still exist the possibility of less restrictive alternatives — e.g. a peer-to-peer content cooperative where, for a single low fee, one can exchange and consume content without restriction; money is then distributed to content creators in proportion to the demand for and use of their content.

I heard that such an alternative could theoretically be implemented on the state level, with every citizen paying a single low tax (less than $10 per year) giving them unfettered access to all published media, and easily maintaining the profit margins of media industries.

I heard that, while such a scheme is highly unlikely to be implemented in the United States, a similar proposal is in early stages of debate in the French parliament.

![]()

And I heard a lot about peer-to-peer…

I heard that p2p is not just a way to exchange files or information, it is a paradigm shift that is totally changing the way societies communicate, trade, and build.

I heard that between 1840 and 1850 the first newspapers appeared in America that could be said to have mass circulation. I heard that as a result — in the space of that single decade — the cost of starting a print daily rose approximately %250.

I heard that modern democracies have basically always existed within a mass media system, a system that goes hand in hand with a centralized, mass-market capital structure.

I heard that we are now moving into a radically decentralized capital structure based on social modes of production in a peer-to-peer information commons, in what is essentially a new chapter for democratic societies.

I heard that the public sphere will never be the same again.

I heard that emerging practices of “remix culture” are in an apprentice stage focused on popular entertainment, but will soon begin manifesting in higher stakes arenas (as suggested by politically charged works like “The French Democracy” or this latest Black Lantern video about the Stanley Williams execution in California).

I heard that in a networked information commons the potential for political critique, free inquiry, and citizen action will be greatly increased.

I heard that whether we will live up to our potential is far from clear.

I heard that there is a battle over pipes, the outcome of which could have huge consequences for the health and wealth of p2p.

I heard that since the telecomm monopolies have such tremendous influence on policy, a radical deregulation of physical network infrastructure is likely in the near future.

I heard that this will entrench those monopolies, shifting the balance of the internet to consumption rather than production.

I heard this is because pre-p2p business models see one-way distribution with maximum control over individual copies, downloads and streams as the most profitable way to move content.

I heard also that policing works most effectively through top-down control over broadband.

I heard that the Chinese can attest to this.

I heard that what we need is an open spectrum commons, where connections to the network are as distributed, decentralized, and collaboratively load-sharing as the network itself.

I heard that there is nothing sacred about a business model — that it is totally dependent on capital structures, which are constantly changing throughout history.

I heard that history is shifting in a big way.

I heard it is shifting to p2p.

I heard this is the most powerful mechanism for distributing material and intellectual wealth the world has ever seen.

I heard, however, that old business models will be radically clung to, as though they are sacred.

I heard that this will be painful.

the economics of open content

For the next two days, Ray and I are attending what hopes to be a fascinating conference in Cambridge, MA — The Economics of Open Content — co-hosted by Intelligent Television and MIT Open CourseWare.

This project is a systematic study of why and how it makes sense for commercial companies and noncommercial institutions active in culture, education, and media to make certain materials widely available for free–and also how free services are morphing into commercial companies while retaining their peer-to-peer quality.

They’ve assembled an excellent cross-section of people from the emerging open access movement, business, law, the academy, the tech sector and from virtually every media industry to address one of the most important (and counter-intuitive) questions of our age: how do you make money by giving things away for free?

Rather than continue, in an age of information abundance, to embrace economic models predicated on information scarcity, we need to look ahead to new models for sustainability and creative production. I look forward to hearing from some of the visionaries gathered in this room.

More to come…

the future of academic publishing, peer review, and tenure requirements

There’s a brilliant guest post today on the Valve by Kathleen Fitzpatrick, english and media studies professor/blogger, presenting “a sketch of the electronic publishing scheme of the future.” Fitzpatrick, who recently launched ElectraPress, “a collaborative, open-access scholarly project intended to facilitate the reimagining of academic discourse in digital environments,” argues convincingly why the embrace of digital forms and web-based methods of discourse is necessary to save scholarly publishing and bring the academy into the contemporary world.

In part, this would involve re-assessing our fetishization of the scholarly monograph as “the gold standard for scholarly production” and the principal ticket of entry for tenure. There is also the matter of re-thinking how scholarly texts are assessed and discussed, both prior to and following publication. Blogs, wikis and other emerging social software point to a potential future where scholarship evolves in a matrix of vigorous collaboration — where peer review is not just a gate-keeping mechanism, but a transparent, unfolding process toward excellence.

There is also the question of academic culture, print snobbism and other entrenched attitudes. The post ends with an impassioned plea to the older generations of scholars, who, since tenured, can advocate change without the risk of being dashed on the rocks, as many younger professors fear.

…until the biases held by many senior faculty about the relative value of electronic and print publication are changed–but moreover, until our institutions come to understand peer-review as part of an ongoing conversation among scholars rather than a convenient means of determining “value” without all that inconvenient reading and discussion–the processes of evaluation for tenure and promotion are doomed to become a monster that eats its young, trapped in an early twentieth century model of scholarly production that simply no longer works.

I’ll stop my summary there since this is something that absolutely merits a careful read. Take a look and join in the discussion.

blog meeting in la-la land

The Chronicle of Higher Education has published a positive piece on blogging in academia, a first person account by Rebecca Goetz, one of the first academic bloggers, of how blogging can actually enhance scholarly life, foster trans-disciplinary communication, and connect the academy to the public sphere.

The timing of Goetz’s article is auspicious, as the institute is currently grappling with these very issues, gearing up for a grant proposal to do something big. Last week, about to dash out the door for the airport, I mentioned this project we’re cooking up to encourage, promote and organize academic blogging with the aim of raising its status as a scholarly activity. Well, last Friday in Los Angeles we assembled a cadre of over a dozen blog-oriented professors, grad students, and journalism profs, along with a radical blogger-librarian, a grassroots media producer, and a sociologist, for a day of stimulating discussion about what can happen when you put blogs in the hands of people who really know something about something.

We’re still sifting through notes and thoughts from the meeting, and for anyone who’s interested we’ve devoted an entire blog to continuing the discussion. I guess you could say we’ve formed a little community dedicated to answering the big questions — chiefly, how the blogging medium might serve as a bridge between the world of scholarly knowledge and the world at large — and to helping us form the proposal for a project — a website? a network? a new sort of blog? — that will address some of these questions.

John Mohr, the afore-mentioned sociologist, described it as a matter of “marshaling and re-deploying intellectual capital,” which I think brilliantly and succinctly captures the possibilities of blogs both for making the academy more transparent and for helping it reach the general public, shining the light of knowledge, as it were, on the complexity of human affairs. The power of blogs is that they exist in a space all their own, not entirely within the academy and not (at least not yet) within the economic and editorial structures of mass media. Because of this, bloggers are able to maintain what McKenzie Wark calls “a slight angle of difference” from both sides. We here at the institute, from our not-quite-inside-not-quite-outside-the-academy vantage, are interested in simultaneously protecting that angle and boosting its stature.

Back in May, I saw Wark speak at a conference on new media education at CUNY called “Share, Share Widely.” He talked about how the academy should position itself in the media-saturated society and how it can employ new media tools (like blogging) to penetrate, and even redefine, the public sphere. I was mulling this over leading up to the meeting and it seems even more dead-on now:

“This tension between dialogue and discourse might not be unrelated to that between education and knowledge. Certainly what the new media technologies offer is a way of constructing new possibilities for the dialogic, ones which escape the boundaries of discipline, even of the university itself. New media is not interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary. It is antidisciplinary — although one might be careful where and to whom we break this news. Its acid with which to eat away at the ossified structure of discourse — with the aim of constructing a new structure of discourse. One that might bring closer together the university with its outside. Not to erase the precious interiority of the university, but to make it porous. To actually apply all that ‘theory’ we learned to our own institutions.”

“Imagine a political refugee, fleeing one country for another, jotting down his thoughts on the run, sharing them with his friends. I’m talking about Marx, writing the 1844 manuscripts. I think critical theory was always connected to new media practices. I think it was always about rethinking the discourse in which dialogue is possible. I think it was always knowledge escaping from the institutions of education. Think of Gramsci editing New Order, negotiating between metropolitan and subaltern languages. Think of Benjamin’s One Way Street, a pamphlet with bold typographic experiments. Or Brecht’s experiments in cinema. Or Debord’s last — amazing — TV program. Broadcast only once so you had to set your vcr. Or the Frankfurt School and Birmingham Schools, which broke down the intellectual division of labor. Or the autonomous studio Meilville built for Godard.”

“We need to do a ‘history of the present’ as Foucault would say, and recover the institutional aspect of knowledge as an object of critique. But of more than critique as well. Let’s not just talk about the ‘public sphere’. Let’s build some! We have the tools. We know wiki and blogging and podcasting. Let’s build new relations between theory and practice. No more theory without practice — but no more practice without theory either. Let’s work at slight angle of difference from the institution. Not against it — that won’t get you tenure — but not capitulating to it either. That won’t make any difference or be interesting to anybody.”