A while back – last March – there was a great deal of excitement over Wikipodia, an open source project to install Wikipedia on an iPod. Wanting a portable Wikipedia, I installed Linux on my brand new video iPod, a necessary prerequisite, but was disappointed to discover that Wikipodia only worked on older iPods with smaller screens. I’ve waited for an update to Wikipodia since then, but the project seems to have gone dark. Probably Wikipodia wouldn’t have been an ideal solution anyway: it requires you to reboot your iPod into Linux whenever you want to look at Wikipedia. You could have an iPod to listen to music or a Wikipedia to read, but not both at the same time.

But a partial fulfillment for my desire to have a portable Wikipedia has come along: Matt Swann has posted a script that puts some of the Wikipedia on an iPod, in iPod Notes format. While it’s much simpler than installing a new operating system on your iPod, it’s still not for everybody – it requires using the OS X command line, although there’s an Automator-based version that’s a bit simpler. (PC versions would seem to be available as well, though I don’t know anything about them – check the comments here.) If you’re willing to take the plunge, you can feed the script a page from Wikipedia and it will start filling up your iPod Notes directory with that page and all the pages linked from it. I started from the entry for book; the script downloaded this, then it downloaded the entries for paper, parchment, page, and so on. When it finished those, it downloads all the pages linked from the linked pages, and it keeps doing this until it runs out of space: regardless of iPod size, you can only have 1000 notes in the Notes directory. This doesn’t meant that you get 1000 articles. Because each iPod note can only be 4 kb long, entries that are longer than 4000 characters are split into multiple notes; thus, I wound up with only 216 entries.

But a partial fulfillment for my desire to have a portable Wikipedia has come along: Matt Swann has posted a script that puts some of the Wikipedia on an iPod, in iPod Notes format. While it’s much simpler than installing a new operating system on your iPod, it’s still not for everybody – it requires using the OS X command line, although there’s an Automator-based version that’s a bit simpler. (PC versions would seem to be available as well, though I don’t know anything about them – check the comments here.) If you’re willing to take the plunge, you can feed the script a page from Wikipedia and it will start filling up your iPod Notes directory with that page and all the pages linked from it. I started from the entry for book; the script downloaded this, then it downloaded the entries for paper, parchment, page, and so on. When it finished those, it downloads all the pages linked from the linked pages, and it keeps doing this until it runs out of space: regardless of iPod size, you can only have 1000 notes in the Notes directory. This doesn’t meant that you get 1000 articles. Because each iPod note can only be 4 kb long, entries that are longer than 4000 characters are split into multiple notes; thus, I wound up with only 216 entries.

Though 216 entries is a tiny subset of Wikipedia, it’s still an interesting experience having a chunk of an encyclopedia in your pocket. What I find most captivating about approaching Wikipedia this was is that I found myself browsing interesting sounding articles rather than searching them directly. The iPod doesn’t have much input functionality: while you can scroll through the list of entries, you can’t search for a subject, as you usually would. (And with only 216 entries, searching would be of limited utility at best. The Wikipodia project promises full text searching, though text entry is a difficult proposition when you only have five keys to type with.) While you can scroll through the list of entries to find something that looks interesting, you’re likely to get sidetracked by something along the way. So you browse.

To my mind, browsing is one of the primary virtues of a print encyclopedia: the arbitrary logic of alphabetization makes for a serendipitous reading experience, and you often come away from a print encyclopedia having read something in a nearby article that you didn’t intend to read. This is something that’s generally lost with online reference works: links between articles are supposed to make logical sense. This is also a reflection of our reading behavior: if I search for “book” in Wikipedia, I’m probably looking for something in particular. If I’m interested in book conservation issues, I might click on the link for slow fires. If I’m interested in some other area related to books – how to make vellum, for example – I almost certainly wouldn’t. Instead I’d click on the vellum link and keep looking from there. We tend to be goal-directed when we using Wikipedia online: it’s like going to a library and finding the specific book you want. Wandering in a library is an equally valid behavior: that’s what happens here.

To my mind, browsing is one of the primary virtues of a print encyclopedia: the arbitrary logic of alphabetization makes for a serendipitous reading experience, and you often come away from a print encyclopedia having read something in a nearby article that you didn’t intend to read. This is something that’s generally lost with online reference works: links between articles are supposed to make logical sense. This is also a reflection of our reading behavior: if I search for “book” in Wikipedia, I’m probably looking for something in particular. If I’m interested in book conservation issues, I might click on the link for slow fires. If I’m interested in some other area related to books – how to make vellum, for example – I almost certainly wouldn’t. Instead I’d click on the vellum link and keep looking from there. We tend to be goal-directed when we using Wikipedia online: it’s like going to a library and finding the specific book you want. Wandering in a library is an equally valid behavior: that’s what happens here.

Because you’re not looking for a particular piece of information, you do find yourself reading in a different way. Search-based reading is a different style of reading than browsing, which is slower and more casual. This has a downside when applied to Wikipedia: the often atrocious style is more glaring when you’re reading for pleasure rather than reading for information. And an offline Wikipedia inhibits some of the new reading habits Wikipedia encourages. I caught myself wondering how biased the declarations of the Shāhnāma‘s originality w/r/t other national epics were; without recourse to page histories and talk pages I’m left to wonder until I find myself with an Internet connection.

The experience of reading Wikipedia this way isn’t perfect: many links don’t work, and some articles seem to arbitrarily end, some in mid-sentence, some in mid-word. You also realize how many links in Wikipedia aren’t useful at all. If I’m interested in books as a concept, I’m probably not interested in 1907 as a concept, though that is the year that Marc Aurel Stein found The Diamond Sutra, the oldest known block-printed book. Marc Aurel Stein or The Diamond Sutra might be interesting subjects to a book-inclined browser; 1907 isn’t as likely. What you get on your iPod is an arbitrary selection. But there’s something very pleasant about this: it’s nice to have the chance to learn about both Neferirkare Kakai and the Rule of St. Benedict on the subway.

The experience of reading Wikipedia this way isn’t perfect: many links don’t work, and some articles seem to arbitrarily end, some in mid-sentence, some in mid-word. You also realize how many links in Wikipedia aren’t useful at all. If I’m interested in books as a concept, I’m probably not interested in 1907 as a concept, though that is the year that Marc Aurel Stein found The Diamond Sutra, the oldest known block-printed book. Marc Aurel Stein or The Diamond Sutra might be interesting subjects to a book-inclined browser; 1907 isn’t as likely. What you get on your iPod is an arbitrary selection. But there’s something very pleasant about this: it’s nice to have the chance to learn about both Neferirkare Kakai and the Rule of St. Benedict on the subway.

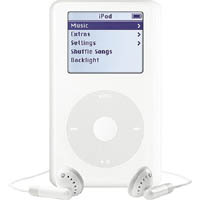

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.

The iPod is, as skeptics initially complained, little more than a hard drive with earphones. But this is precisely its genius: the simplicity of its interface, the sleekness of its form, the radical smallness of its immense storage capacity. All these allow us to spend less time sorting through our music — lugging around stacks of albums, ejecting and inserting tapes or discs — and more time listening to it.