There’s an interesting piece by Cory Doctorow in Locus Magazine, a sci-fi and fantasy monthly, entitled “You Do Like Reading Off a Computer Screen.” discussing the differences between on and offline reading.

The novel is an invention, one that was engendered by technological changes in information display, reproduction, and distribution. The cognitive style of the novel is different from the cognitive style of the legend. The cognitive style of the computer is different from the cognitive style of the novel.

Computers want you to do lots of things with them. Networked computers doubly so — they (another RSS item) have a million ways of asking for your attention, and just as many ways of rewarding it.

And he illustrates his point by noting throughout the article each time he paused his writing to check an email, read an RSS item, watch a YouTube clip etc.

I think there’s more that separates these forms of reading than distracted digital multitasking (there are ways of reading online reading that, though fragmentary, are nonetheless deep and sustained), but the point about cognitive difference is spot on. Despite frequent protestations to the contrary, most people have indeed become quite comfortable reading off of screens. Yet publishers still scratch their heads over the persistent failure of e-books to build a substantial market. Befuddled, they blame the lack of a silver bullet reading device, an iPod for books. But really this is a red herring. Doctorow:

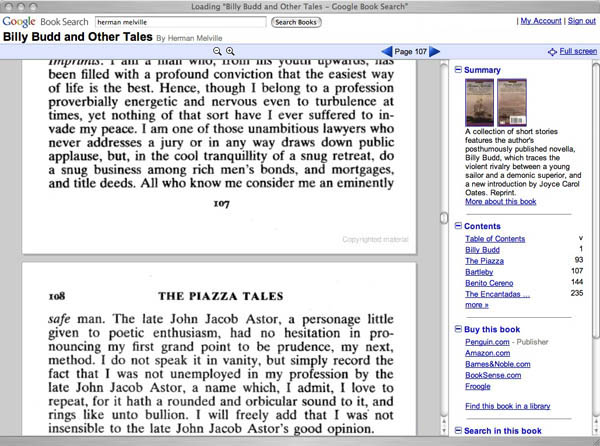

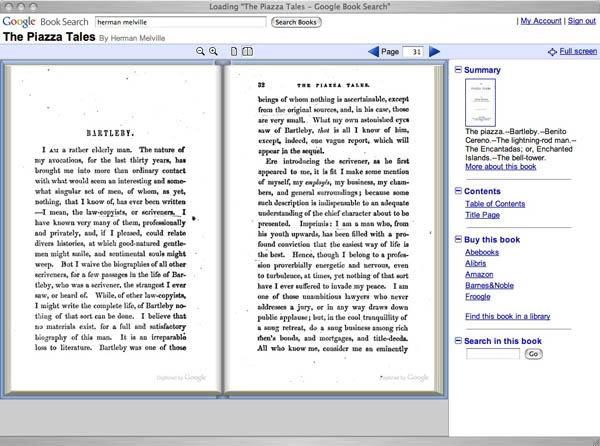

The problem, then, isn’t that screens aren’t sharp enough to read novels off of. The problem is that novels aren’t screeny enough to warrant protracted, regular reading on screens.

Electronic books are a wonderful adjunct to print books. It’s great to have a couple hundred novels in your pocket when the plane doesn’t take off or the line is too long at the post office. It’s cool to be able to search the text of a novel to find a beloved passage. It’s excellent to use a novel socially, sending it to your friends, pasting it into your sig file.

But the numbers tell their own story — people who read off of screens all day long buy lots of print books and read them primarily on paper. There are some who prefer an all-electronic existence (I’d like to be able to get rid of the objects after my first reading, but keep the e-books around for reference), but they’re in a tiny minority.

There’s a generation of web writers who produce “pleasure reading” on the web. Some are funny. Some are touching. Some are enraging. Most dwell in Sturgeon’s 90th percentile and below. They’re not writing novels. If they were, they wouldn’t be web writers.

On a related note, Teleread pointed me to this free app for Macs called Tofu, which takes rich text files (.rtf) and splits them into columns with horizontal scrolling. It’s super simple, with only a basic find function (no serious search), but I have to say that it does a nice job of presenting long print-like texts. By resizing the window to show fewer or more columns you can approximate a narrowish paperback or spread out the text like a news broadsheet. Clicking left or right slides the view exactly one column’s width — a simple but satisfying interface. I tried it out with Doctorow’s piece:

I also plugged in Gamer Theory 2.0 and it was surprisingly decent. Amazing what a little extra thought about the screen environment can accomplish.

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together.

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together. If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.

If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.