Yesterday Adobe announced the release of their Digital Editions software. The software’s been available in a beta format for a while; I downloaded it back then & didn’t think it was interesting enough to write about. I’ve spent the past two days playing with the new release. I’m still not sure that it’s worth attention, but I’ll try to explain why it’s not interesting.

What is Digital Editions? It’s still a bit hard to tell. When I downloaded the beta version, it seemed to be a lightweight remake of Adobe Reader (née Acrobat Reader), Adobe’s PDF viewer. The full release expands the capabilities of Digital Editions: in addition to being a PDF viewer, it’s also a viewer for the new EPUB format. It also seems to be a front end for future web-based electronic book sellers, like Apple’s iTunes for music. I’ll go through each of these three uses in turn, but first a few notes on how Digital Editions works.

Digital Editions looks more like a web application than a desktop application. There are no menu bars to speak of, and its interface borrows nothing from the operating system. This is nice in that it feels like it’s a reading environment: the interface is black-on-black, which should block out the distractions rampant on the desktop. Certainly there’s none of the excess frippery that comes with Acrobat. However, the minimalism may be a bit excessive: it can be difficult to find black buttons and sliders to turn pages. (I’d be curious to see a review of the application from someone interested in accessibility for the disabled.) And some controls don’t behave the way a user might expect: given a scrollbar along the right edge of a page, I expect to be able to click at a point where the slider isn’t to move the slider. No such luck. Nor can you drag-select to change which part of the page is visible when the page is larger than the window, or drag a file into the window to open it.

Many of my problems with it stem from it not behaving like Mac software; I suspect a PC user would have similar complaints about it not behaving like PC software. This wouldn’t matter if the interface were an improvement over the operating systems – in both there’s plenty of room for improvement – but it’s not a noticeable improvement. It’s simply different, and that slows users down.

1. as a PDF reader

As mentioned above, Digital Editions initially seemed to be a remake of Adobe Reader, which has become hideously bloated with time. The current OS X version of the software is 108Mb; it’s a slow program. While I look at a fair number of PDFs on a daily basis, I’ve long since stopped using Acrobat in any of its forms if I don’t have to; Apple’s Preview application is much faster and delivers almost all the functionality that I want out of a PDF reader. I suspect most other Mac users do the same. Acrobat can be useful if you’re doing print pre-press work or working with forms, but neither of those are things I do that often.

Digital Editions does work as a PDF viewer. It’s based around a library concept, so every time you open a PDF in DE, an image of the front page is saved in the library; you can click on this image to open it. Once you have a PDF, you can look at it as a single page, as a double page (even if the PDF hasn’t been set up for this), at the width of the screen, or with a zoom widget that lets you use 18 levels of zoom from 87% to 919%. Here’s how a PDF from /ubu editions looks:

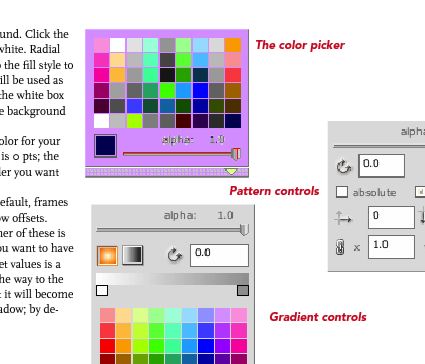

Digital Editions is clearly built around a different PDF rendering engine than the rest of Adobe’s software. (The FAQ explains that this engine was designed to be used on cellphones.) Image quality is noticeably worse than in Acrobat or Preview. Text is poorly aliased, and spacing between characters seems to be off for some fonts at some zoom levels. Graphics are notably grainy, and weird rendering artifacts sometimes show up. (In the image above, for example, note that there’s a light blue rectangle under the text on the left. This doesn’t show up in any other PDF viewer.) Some PDFs have extras that shouldn’t have been there, blocks of background color, for example. One illustration of the color picker in the Sophie help PDF I made a couple weeks back turns a lovely shade of purple:

This is frustrating: one of Adobe’s chief selling points of PDF as a format has been that a PDF will look the same on every machine in every viewer. Not this one. Adobe offers sample PDFs for download at their Digital Editions website (see below), which are similarly perplexing. Although these appear to be ordinary PDFs (with no restrictions), they don’t behave like regular PDFs. They can’t be opened in any PDF viewer that’s not Digital Editions. Preview shows only blank pages; opening them in the current Adobe Reader takes you to a webpage where you can download Digital Editions; and opening them in an older version of Acrobat brings up a message asking whether I’d like to learn more about documents protected with Adobe DRM. Clicking yes takes me to a pre-Digital Editions Adobe ebooks page. PDFs have become popular because they can be used in a variety of ways across a variety of platforms. This seems like a significant step backwards for Adobe: interoperability is taking a back seat to DRM.

2. as an EPUB reader

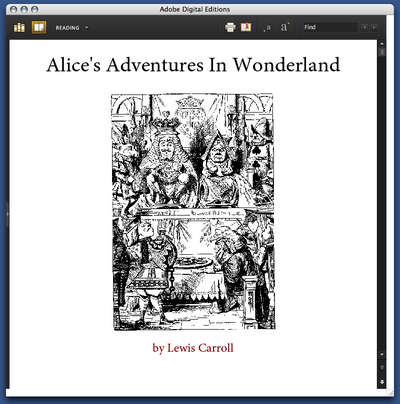

But Digital Editions isn’t only a PDF viewer; it’s also a viewer for EPUB format. EPUB is the work of the IDPF; it’s essentially an XHTML format for ebooks. You can get sample EPUBs from Adobe’s website. If you have the latest version of Adobe InDesign, you can make them yourself (more about that in a bit). Here’s the front page of their edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

Perhaps not surprisingly for an XHTML format, the experience of reading an EPUB in Digital Editions is similar to reading a web page. The text becomes as wide as the Digital Editions window; if the window is wide enough, the text may reflow into more columns. When this happens is unclear to me: in some books, the text column is much too wide to read well before the text is reflowed:

You can choose between 4 different font sizes; you can’t change the fonts. (Some EPUB books include their own fonts; some use system fonts.) As in the Digital Editions PDF viewer, there’s some bookmarking capability: you can select text and click “Add bookmark” to add a note at a particular point in the text. Books have tables of contents; there’s a search function. You can print books (or, on a Mac, convert them to PDFs); this seems to be in two columns by default.

That seems to be all you can do with these books. The books that Adobe provides are noticeably ugly: most of the graphics included are low resolution. Text looks weirdly bad: in the default font, the italic text seems to actually be slanted roman characters, which you’d think Adobe would be embarrassed about. To my eye, the text looks much better in Safari or even Firefox. You can make this comparison if you rename the .epub file .zip and unzip it; in the resulting folder, you’ll find a bunch of HTML pages, the images used, and fonts, if they’re included.

Adobe trumpets the one-click creation of EPUB files in the new version of InDesign. So I fired up InDesign and made some EPUBs to see how those worked in Digital Editions. Try for yourself: here is a version of the Sophie help PDF in EPUB format. The results are a bit disappointing: all the graphics have been dumped at the end of the document, much of the formatting has been lost, and the table of contents I laboriously set up for PDF export has been eliminated. One-click conversion evidently doesn’t allow exporting the fonts the document uses; and even though I have the Avenir and Scala fonts on my machine, it displays in the default Digital Editions font. The graphics do display in their real color, which is more than you can say for the way Digital Editions handles the PDF, though many of them do seem to have been converted to JPEGs in a lossy way.

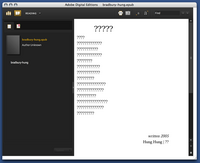

As a whim, I fed InDesign’s converter some foreign-language poetry to see how it would handle Unicode text. French came through okay. Lithuanian was mangled beyond recognition. Some Chinese poetry didn’t work at all:

It’s clear that this needs a lot of work before it can be taken seriously.

3. as a store

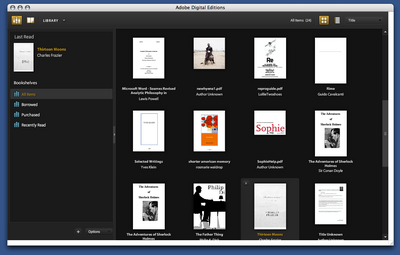

From Adobe’s press release, it’s clear that the main impetus behind Digital Editions is to provide a local front end for web-based selling of ebooks. The model that Adobe is working on becomes apparent when you open it up: the program maintains a library of all the PDF files you look at, in the same way that iTunes maintains a library of the MP3s on your computer:

Categories of books (on the left in the above screenshot) include “Borrowed” and “Purchased”. The iTunes model of incorporating a store in software isn’t necessarily a bad one: Linotype has embedded a font store in their free font management software, with some degree of success. It’s hard to tell how well Adobe’s integration will work. They’ve tried selling ebooks before with little success; I have a couple of PDFs bought from Amazon that I’ve long since despaired of ever opening again. (Some progress may be reported: clicking on these now now opens DigitalEditions, where I get a different cryptic error than I did before in Acrobat.) The same sort of problems are likely with ebooks designed for DigitalEditions; it does worry me that even PDFs without DRM can’t be opened outside of the software.

DRM are probably the logical place to end this overlong review. One of the major reasons that we haven’t spent much time covering the efforts of the IDPF is that it’s devoted to standards that satisfy producers rather than consumers; many producers are concerned with locking down their products as thoroughly as possible. It may be a reasonable position from their perspective, but it’s resulted in products that aren’t particularly useful to consumers. DigitalEditions looks like it might be a big piece in the puzzle for DRM-focused producers. Unfortunately, readers are being neglected.

As for the device, well, the

As for the device, well, the