If you’re in the New York area, this Wednesday I’ll be giving a talk at an event organized by the Brooklyn College Library called “It’s All About the Book.” Also speaking will be Jason Epstein, one of the all-time great innovators in print publishing, and founder most recently of On Demand Books. Talks will be followed by a tour of “books as art” installations by a number of local artists, curators and librarians. It promises to be an interesting event, well worth the trek to Flatbush.

Category Archives: publishing

gamer theory 2.0

…is officially live! Check it out. Spread the word.

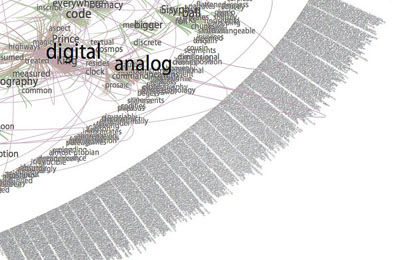

I want to draw special attention to the Gamer Theory TextArc in the visualization gallery – a graphical rendering of the book that reveals (quite beautifully) some of the text’s underlying structures.

Gamer Arc detail

TextArc was created by Brad Paley, a brilliant interaction designer based in New York. A few weeks ago, he and Ken Wark came over to the Institute to play around with the Gamer Theory in TextArc on a wall display:

Ken jotted down some of his thoughts on the experience: “Brad put it up on the screen and it was like seeing a diagram of my own writing brain…” Read more here (then scroll down partway).

starting bottom-left, counter-clockwise: Ken, Brad, Eddie, Bob

More thoughts about all of this to come. I’ve spent the past two days running around like a madman at the Digital Library Federation Spring Forum in Pasadena, presenting our work (MediaCommons in particular), ducking in and out of sessions, chatting with interesting folks, and pounding away at the Gamer site — inserting footnote links, writing copy, generally polishing. I’m looking forward to regrouping in New York and processing all of this.

Thanks, Florian Brody for the photos.

Oh, and here is the “official” press/blogosphere release. Circulate freely:

The Institute for the Future of the Book is pleased to announce a new edition of the “networked book” Gamer Theory by McKenzie Wark. Last year, the Institute published a draft of Wark’s path-breaking critical study of video games in an experimental web format designed to bring readers into conversation around a work in progress. In the months that followed, hundreds of comments poured in from gamers, students, scholars, artists and the generally curious, at times turning into a full-blown conversation in the manuscript’s margins. Based on the many thoughtful contributions he received, Wark revised the book and has now published a print edition through Harvard University Press, which contains an edited selection of comments from the original website. In conjunction with the Harvard release, the Institute for the Future of the Book has launched a new Creative Commons-licensed, social web edition of Gamer Theory, along with a gallery of data visualizations of the text submitted by leading interaction designers, artists and hackers. This constellation of formats — read, read/write, visualize — offers the reader multiple ways of discovering and building upon Gamer Theory. A multi-mediated approach to the book in the digital age.

http://web.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/

More about the book:

Ever get the feeling that life’s a game with changing rules and no clear sides, one you are compelled to play yet cannot win? Welcome to gamespace. Gamespace is where and how we live today. It is everywhere and nowhere: the main chance, the best shot, the big leagues, the only game in town. In a world thus configured, McKenzie Wark contends, digital computer games are the emergent cultural form of the times. Where others argue obsessively over violence in games, Wark approaches them as a utopian version of the world in which we actually live. Playing against the machine on a game console, we enjoy the only truly level playing field–where we get ahead on our strengths or not at all.

Gamer Theory uncovers the significance of games in the gap between the near-perfection of actual games and the highly imperfect gamespace of everyday life in the rat race of free-market society. The book depicts a world becoming an inescapable series of less and less perfect games. This world gives rise to a new persona. In place of the subject or citizen stands the gamer. As all previous such personae had their breviaries and manuals, Gamer Theory seeks to offer guidance for thinking within this new character. Neither a strategy guide nor a cheat sheet for improving one’s score or skills, the book is instead a primer in thinking about a world made over as a gamespace, recast as an imperfect copy of the game.

——————-

The Institute for the Future of the Book is a small New York-based think tank dedicated to inventing new forms of discourse for the network age. Other recent publishing experiments include an annotated online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report (with Lapham’s Quarterly), Without Gods: Toward a History of Disbelief (with Mitchell Stephens, NYU), and MediaCommons, a digital scholarly network in media studies. Read the Institute’s blog, if:book. Inquiries: curator [at] futureofthebook [dot] org

McKenzie Wark teaches media and cultural studies at the New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College in New York City. He is the author of several books, most recently A Hacker Manifesto (Harvard University Press) and Dispositions (Salt Publishing).

gamer theory 2.0 (beta)

The new Gamer Theory site is up, though for the next 24 hours we’re considering it beta. It’s all pretty much there except for some last bits and pieces (pop-up textual notes, a few explanatory materials, one or two pieces for the visualization gallery, miscellaneous tweaks). By all means start poking around and posting comments.

The project now has a portal page that links you to the constitutent parts: the Harvard print edition, two networked web editions (1.1 and 2.0), a discussion forum, and, newest of all, a gallery of text visualizations including a customized version of Brad Paley’s “TextArc” and a fascinating prototype of a progam called “FeatureLens” from the Human-Computer Interaction Lab at the University of Maryland. We’ll make a much bigger announcement about this tomorrow. For now, consider the site softly launched.

gamer theory update

Gamer Theory 2.0 is nearly there, we’re just taking a few extra few days to apply the finishing touches and to get a few last visualizations mounted in the gallery. The print edition from Harvard is available now.

For those of you in the city, there’s a great Gamer Theory event planned for tonight at the New School followed by drinks in Brooklyn at Barcade — a bar (as the name suggests) fitted out as a retro video game arcade (have a pint and play a round of Rampage, Gauntlet or Frogger). Here’s more info:

what: McKenzie Wark will present, and lead a discussion of his new book Gamer Theory (Harvard University Press). Jaeho Kang (Sociology, The New School for Social Reseach) will act as the respondent.

where: Wolff Conference Room, 2nd floor, 65 5th avenue (between 14th and 13th streets)

when: 6-8PM, Wednesday 18th April 2007

then: drinks & games at Barcade, 388 Union Ave Williamsburg (L train to Lorrimer st, take Union exit)

samizdat express

In his latest NY Times column, Edward Rothstein meditates on the vastness of the public domain and the pleasures of skimming it in simple digital editions prepared by B+R Samizdat Express. Since 1993 B+R, run by Barbara and Richard Seltzer of West Roxbury, Massachusetts, has been selling bundles of plain text (ASCII) digital literature scooped from Project Gutenberg and arranged by theme, genre or period into anthologies — first on floppy disc, and now on CD-ROM and DVD. It’s all stuff you can get for free by grazing the web’s various public domain repositories, but B+R have done the work of harvesting and sorting and they’ll ship these multi-shelf-spanning chunks to you for the price of a single print volume. Browse through nearly 200 book collections they’ve assembled so far and you’ll find packages ranging from “Anthropology and Myth” ($19), “Works of Guy de Maupassant” ($12), or “The American Revolution and Early Republic as witnessed by Mercy Warren and Others” ($19). Some works are provided in audio through text-to-voice conversion software.

As Rothstein notes, the bare-bones formatting and sheer volume of the anthologies makes these works hard to digest, but there’s no doubt B+R provides a valuable service, especially for people in places where books are scarce and net access unreliable. All in all, it’s an e-book advocate’s playground but more of a hallucinogenic head trip for the average reader — a way to sample vastness. It does make one’s wheels start to turn, though, on what other elucidating layers could be built on top of the vast murk of the digital library.

dismantling the book

Peter Brantley relates the frustrating experience of trying to hunt down a particular passage in a book and his subsequent painful collision with the cold economic realities of publishing. The story involves a $58 paperback, a moment of outrage, and a venting session with an anonymous friend in publishing. As it happens, the venting turned into some pretty fascinating speculative musing on the future of books, some of which Peter has reproduced on his blog. Well worth a read.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

A particularly interesting section (quoted further down) is on the implications for publishers of on-demand disaggregated book content: buying or accessing selected sections of books instead of entire volumes. There are numerous signs that this will be at least one wave of the future in publishing, and should probably prod folks in the business to reevaluate why they publish certain things as books in the first place.

Amazon already provides a by-the-page or by-the-chapter option for certain titles through its “Pages” program. Google presumably will hammer out some deals with publishers and offer a similar service before too long. Peter Osnos’ Caravan Project includes individual chapter downloads and print-on-demand as part of the five-prong distribution standard it is promoting throughout the industry. If this catches on, it will open up a plethora of options for readers but it might also unvravel the very notion of what a book is. Could we be headed for a replay of the mp3’s assault on the album?

The wholeness of the book has to some extent always been illusory, and reading far more fragmentary than we tend to admit. A number of things have clouded our view: the economic imperative to publish whole volumes (it’s more cost-effective to produce good aggregations of content than to publish lots of individual options, or to allow readers to build their own); romantic notions of deep, cover-to-cover reading; and more recently, the guilty conscience of the harried book consumer (when we buy a book we like to think that we’ll read the whole thing, yet our shelves are packed with unfinished adventures).

But think of all the books that you value just for a few particular nuggets, or the books that could have been longish essays but were puffed up and padded to qualify as $24.95 commodities (so many!). Any academic will tell you that it is not only appropriate but vital to a researcher’s survival to hone in on the parts of a book one needs and not waste time on the rest (I’ve received several tutorials from professors and graduate students on the fine art of fileting a monograph). Not all thoughts are book-sized and not all reading goes in a straight line. Selective reading is probably as old as reading itself.

Unbundling the book has the potential to allow various forms of knowledge to find the shapes and sizes that fit them best. And when all the pieces are interconnected in the network, and subject to social discovery tools like tagging, RSS and APIs, readers could begin to assume a role traditionally played by publishers, editors and librarians — the role of piecing things together. Here’s the bit of Peter’s conversation that goes into this:

Peter: …the Google- empowered vision of the “network of books” which is itself partially a romantic, academic notion that might actually be a distinctly net minus for publishers. Potentially great for academics and readers, but potentially deadly for publishers (not to mention librarians). As opposed to the simple first order advantage of having the books discoverable in the first place – but the extent to which books are mined and then inter-connected – that is an interesting and very difficult challenge for publishers.

Am I missing something…?

Friend: If you mean, are book publishers as we know them doomed? Then the answer is “probably yes.” But it isn’t Google’s connecting everything together that’s doing it. If people still want books, all this promotion of discovery will obviously help. But if they want nuggets of information, it won’t. Obviously, a big part of the consumer market that book publishers have owned for 200 years want the nuggets, not a narrative. They’re going, going, gone. The skills of a “publisher” — developing content and connecting it to markets — will have to be applied in different ways.

Peter: I agree that it is not the mechanical act of interconnection that is to blame but the demand side preference for chunks of texts. And the demand is probably extremely high, I agree.

The challenge you describe for publishers – analogous in its own way to that for libraries – is so fundamentally huge as to mystify the mind. In my own library domain, I find it hard to imagine profoundly differently enough to capture a glimpse of this future. We tinker with fabrics and dyes and stitches but have not yet imagined a whole new manner of clothing.

Friend: Well, the aggregation and then parceling out of printed information has evolved since Gutenberg and is now quite sophisticated. Every aspect of how it is organized is pretty much entirely an anachronism. There’s a lot of inertia to preserve current forms: most people aren’t of a frame of mind to start assembling their own reading material and the tools aren’t really there for it anyway.

Peter: They will be there. Arguably, when you look at things like RSS and Yahoo Pipes and things like that – it’s getting closer to what people need.

And really, it is not always about assembling pieces from many different places. I might just want the pieces, not the assemblage. That’s the big difference, it seems to me. That’s what breaks the current picture.

Friend: Yes, but those who DO want an assemblage will be able to create their own. And the other thing I think we’re pointed at, but haven’t arrived at yet, is the ability of any people to simply collect by themselves with whatever they like best in all available media. You like the Civil War? Well, by 2020, you’ll have battle reenactments in virtual reality along with an unlimited number of bios of every character tied to the movies etc. etc. etc. I see a big intellectual change; a balkanization of society along lines of interest. A continuation of the breakdown of the 3-television network (CBS, NBC, ABC) social consensus.

follow the eyes: screenreading reconsidered (again)

From Editor&Publisher (via Print is Dead): The Poynter Institute just released findings from a study in which eye-tracking sensors were used to analyze the behavior of 600 readers across print and online news sources. The resulting data clashes with the usual assumptions:

When readers chose to read an online story, they usually read an average of 77% of the story, compared to 62% in broadsheets and 57% in tabloids…

The study looked at two tabloids, the Rocky Mountain News and Philadelphia Daily News; two broadsheets, the St. Petersburg Times and The Star-Tribune of Minneapolis; and two newspaper Web sites, at the Times and Star-Tribune.

Considering the increasingly disaggregated nature of people’s news-sifting, is “two newspaper websites” really the right test bed for gauging online reading habits? Still, this is a pretty interesting, myth-busting find, though in a way not at all surprising.

This takes us back to the discussion around Cory Doctorow’s recent piece betting on the long-term persistence of print for certain kinds of reading. Print reading, he says, tends toward the sustained and immersive, the long-form linear narrative. Computer reading, on the other hand, is multi-tasky — distracted, social, bite-sized, multidirectional. One could poke a lot of holes in these characterizations, but generally speaking, they do sum up the way in which many of us divide our reading labor (and leisure) across “platforms.” Contrary to popular belief, Doctorow argues, people do like reading on screens. But they also like reading from printed pages. It’s not either/or — the different modes of reading reinforce the different modes of conveyance, paper and PC.

I’ve tended to agree, but many of the folks in the comments here didn’t. They insisted that it’s only a matter of time before we’ll be doing the vast majority of our reading on screens — even the linear, immersive reading that seems most resistant to digital migration. Getting past my own deep attachment to print, and reckoning with how far into daily practice electronic reading has already penetrated in so little time, I have to admit that this is probably true, though I imagine print will likely persist for at least a few more generations, and will always have its uses (and will hopefully be kept as a contingency reserve in case the lights go out).

Ultimately, this is a boring game, betting on which technology will win out. But it’s interesting sometimes to analyze what motivates certain big cultural actors to wager the way they do.

If you think about it, it makes a lot of sense that Doctorow, generally an advocate for new technologies, wants to see print survive, and why despite his progressive edge, he’s a bit of a traditionalist. As a novelist, Doctorow is deeply invested in the economic model of print. That’s the way he actually sells books (and probably the way he likes to read them). And yet he grasps the Internet’s potential to leverage print — his career as a writer took off at precisely the moment when these two worlds entered into a complex symbiosis. As such, he has long been evangelizing the practice of giving away e-books to sell more print books, pointing to his own great success as proof of the hybrid concept.

At the surreal Google conference I attended at the New York Public Library in January, Doctorow took the stage as mollifier-in-chief, soothing the gathered representatives of the publishing industry with assurances that print is here to stay, is in fact reinforced by new online discovery tools like Google Book Search and free e-versions (which he suggests are used primarily for browsing or “market research”). All of this is right and true — for now — and Doctorow’s advice to publishers to loosen up and embrace the Web as a gateway toward offline reading experiences, and as a way to socially situate their texts on the network is good advice, but it doesn’t necessarily shed light on the longer term. The Poynter study, in its crude way, does.

Net-native writing will always be for a distracted audience, print for a captivated one, says Doctorow. He’s comfortable with that split. And I guess I’ve been too, suggesting as it does two sorts of knowledge, neither of which we’d want to lose. But the gap will almost certainly narrow, and figuring out the consequences of that is certainly one of our biggest challenges.

MediaCommons editorial board convenes

Big things are stirring that belie the surface calm on this page. Bob, Eddie and I are down on the Jersey shore with the newly appointed editorial board of MediaCommons. Kathleen and Avi have assembled a brilliant and energetic group all dedicated to changing the forms and processes of scholarly communication in media studies and beyond. We’re thrilled to be finally together in the same room to start plotting out how this initiative will grow from a rudimentary sketch into a fully functioning networked press/community. The excitement here is palpable. Soon we’ll be posting some follow-up notes and a Comment Press edition of a paper by Kathleen. Stay tuned.

blooker nominees

The short list of nominees for Lulu.com’s second annual Blooker Prize, which is given to the year’s best book adapted from or based on a blog (or web comic), has been announced. This piece in the UK Times looks at how some publishers have begun more aggressively talent scouting in the blogosphere.

amazon starts to close the loop

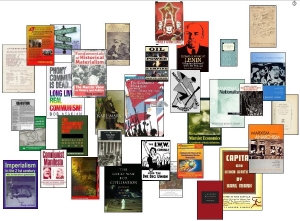

About two and a half years ago, when the institute was first developing the idea of the “networked book,” we started a thought experiment which tries to imagine what would happen if Marx and Engels published the Communist Manifesto today and posted it to the web in a form which captured the extensive “conversation” that the essay provoked. About a year ago i made an image for a talk which cobbled together thumbnails from various books on Amazon which were related to the Communist Manifesto:

The point of the image was that these books, which are a concrete manifestation of the conversation, exist as isolated islands which at best can reference each other but which are not connected in the way we might imagine in the networked world being born.

Well, amidst all the discussion of the pluses and minuses of both Google and Microsoft book search, for the past two years Amazon has been quietly doing something exciting.

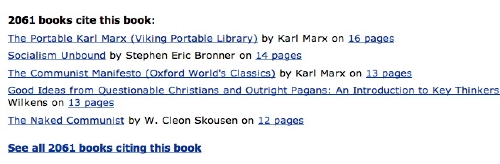

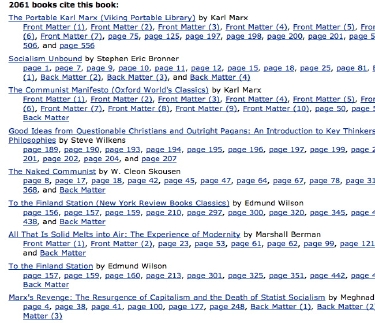

If you go to the Amazon page for an edition of the Communist Manifesto, you’ll see a reference to 2061 books in Amazon’s list which reference the Manifesto with a hot-link to each reference in each of the books.

The only big missing piece is an interactive semantic map with links between all 2061 books.