Once upon a time, a long time ago, I was an editor for Let’s Go, a series of travel guides. While there, I learned a great many things about making books, not all of them useful. One of them: how to make an index. Let’s Go had at that time – maybe it still does, I’m not sure how things are run now – an odd relationship with the publisher of the series, St. Martin’s Press: Let’s Go laid the books out in-house and sent finished files (PostScript in those days) to St. Martin’s, who took care of getting the books printed and in stores. The editors were thus responsible for everything that appeared in the books, from the title page down to the index. Because Let’s Go is staffed by college students, the staff mostly turns over every year; because it was staffed by college students, most of them didn’t know how to edit. Consequently, every year, the tasks involved in editing books must be retaught. And thus it was that one summer I was taught to index a book, and the next summer I found myself teaching others to index books.

As an editor of a book at Let’s Go, you were responsible for creating an index for your book. There’s something to be said to having the person who created the book also controlling how it’s accessed: presumably, the person who put the book together knows what’s important in it and what readers should find in it. The vast majority of the publishing world works differently: generally once a book has been edited, it’s sent off to professional indexers, who independently create an index for the book. There’s an argument for this: knowing how to create an index is specialized knowledge: it’s information architecture, to use the common phrase. It doesn’t necessarily follow that someone who’s good at editing a book will know how to organize an index that will be useful to readers.

But Let’s Go maintained a child-like faith in the malleability of its editors, and editors were made to index their own books, quality be damned. The books were being edited (and typeset) in a program called Adobe FrameMaker, which is generally used to produce technical manuals; in FrameMaker, if you highlight text and press a certain key command, an index window pops up. The index window attaches a reference to the page number of the highlighted text to the book’s index with whatever descriptive text desired. At the end of every week, editors did something called “generating their book”, which updated all the page numbers, giving a page count for the book in progress, and produced an index, which could be scrutinized. In theory, editors were supposed to add terms to their index as they worked; in practice, most ended up racing to finish their index the week before the book was due to be typeset.

It must be admitted that most of the indices constructed in this way were not very good. A lot of index jokes were attempted, not all successfully. (In an Ireland guide, for example, “trad 72” was immediately followed by “traditional music, see trad”. Funny phrases were indexed almost as much as useful topics (in the same book, “giant babies 433” is followed by “giant lobster clutching a Guinness 248”). Friends’ names turned up with an unfortunate frequency. One finds that there’s something casual about an index. If we think of a book as a house, the table of contents is the front door, the way a visitor is supposed to enter. The index is the back door, the one used by friends.

It must be admitted that most of the indices constructed in this way were not very good. A lot of index jokes were attempted, not all successfully. (In an Ireland guide, for example, “trad 72” was immediately followed by “traditional music, see trad”. Funny phrases were indexed almost as much as useful topics (in the same book, “giant babies 433” is followed by “giant lobster clutching a Guinness 248”). Friends’ names turned up with an unfortunate frequency. One finds that there’s something casual about an index. If we think of a book as a house, the table of contents is the front door, the way a visitor is supposed to enter. The index is the back door, the one used by friends.

Thinking about indices in print books isn’t something that happens as much any more. In an era when less and less profit can be made off printed books, niceties like indices often get lost for cost reasons: they both cost money to make and they take pages to print. More and more indices wind up as online-only supplements. Much of the function of the index seems to have been obviated by full-text searching: rather than taking the index’s word for where a particular name appears in a text, it’s much simpler to press command-F to find it.

But while the terms may have changed, the problem of making easy paths into a text hasn’t gone away. The problem of organizing information quickly comes to light when keeping a blog that isn’t strictly time-based like this one: while we set out a few years back with nicely defined categories for posts, we quickly realized that the categories weren’t enough. Like many people, we moved to tags to attempt to classify what we were talking about; our tags, unpruned, are as messy a thicket as the most unwieldy index.

* * * * *

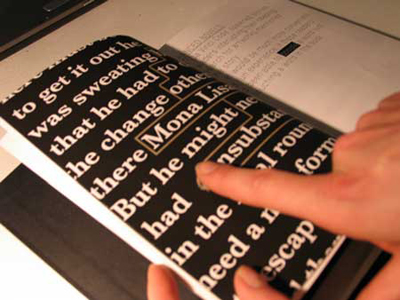

I came across Helen Mirra’s book Cloud, the, 3 last week at 192 Books in Chelsea. I’d seen & liked some of Mirra’s work in a show at Peter Blum in the spring where she had a piece based on Robert Walser, one of my pet favorite writers. It was a thick book for someone I’d thought of as a visual artist: I picked it up & flipped through it, which turns out to be the best way to approach this book: the viewer is left with the impression of an index that’s been exploded or turned into a flip book, an index spread out to cover a whole book. The pages are almost entirely blank, each with an entry or two.

I came across Helen Mirra’s book Cloud, the, 3 last week at 192 Books in Chelsea. I’d seen & liked some of Mirra’s work in a show at Peter Blum in the spring where she had a piece based on Robert Walser, one of my pet favorite writers. It was a thick book for someone I’d thought of as a visual artist: I picked it up & flipped through it, which turns out to be the best way to approach this book: the viewer is left with the impression of an index that’s been exploded or turned into a flip book, an index spread out to cover a whole book. The pages are almost entirely blank, each with an entry or two.

A note at the back explains what the book is: “The preceding text is an index of John Dewey’s Reconstruction in Philosophy (New York: Beacon, 1920), written by Helen Mirra in 2005/6.” An afterword by Lynn Hejinian goes into more detail, including why Mirra is working from this particular volume of Dewey, in which he attempts to bring philosophy to bear on the problems of the real world. But the central idea is simple enough: Mirra constructed her own index to a book. Dewey’s book (the edition Mirra used can be examined here) already has an index, eight stately pages that move through the terms used in Reconstruction in Philosophy from “Absolute reality, 23, 27” to “World, nomenal and phenomenal, 23”.

There’s some overlap between Dewey’s index – is it really his index, constructed by John Dewey himself? – and Mirra’s index. Dewey’s index, for example, contains “Errors, 34”. Mirra’s version contains “Errors, of our ancestors, 35–36”. Mirra’s working from the same book, but her index finds poetry in Dewey’s prose: “Environment, 10, 14, 19; even a clam modifies the, 84; given, 156.” “Color in contrast with pure light, a, 88.” “Habitually reasonable thoughts, 6.” “Half-concealed and half-apologetic life, 210.” “Sailor compared with the weaver, the, 11.” “True method as comparable to the operations of the bee, 32.” Consulting Dewey’s book at those pages reveals that Mirra’s made up nothing. Her index, however, reveals her own personal reading of the book.

Cloud, the, 3 is an artist’s book, a book that is meant to function as an art object rather than being a conduit of information. In a way, this seems perfectly appropriate: in a world where Dewey’s book is fully searchable online, indexing can seem superfluous, no longer a practical concern. (This hasn’t always been the case: Art & Language, a conceptual collective started in the late 1960s, pursued indexing as a Marxist tactic to bring knowledge to the masses.) One can make the argument that in structure Mirra’s book is not that dissimilar from the unwieldy tag cloud that graces the right side of this blog, the “frightful taxonomic bog” that we periodically fret over & fail to do anything about. But I think the object-status of Mirra’s book enables us to think about its contents in a way that, for example, a tagcloud doesn’t: as an object that doesn’t need to exist, we question its existence and wonder why it is accorded financial value. A tag cloud, all too often, is just one more widget. I like Mirra’s book because it didn’t have to exist: the artist had to work to create it.

* * * * *

Most of the publishing industry doesn’t follow Let’s Go’s example: in general, it’s much more hierarchical. Writers write, editors edit, indexers index, and typesetters typeset. Perhaps it’s economically necessary to have everyone specialize in this way; however, there’s an inefficiency built into this system which necessitates that people less familiar with the text are constructing the ways into it. On the Internet, by contrast, we increasingly realize that we are all editors now. We could all be indexers too.