digitalculturebooks, a collaborative imprint of the University of Michigan press and library, publishes an annual anthology of the year’s best technology writing. The nominating process is open to the public and they’re giving people until January 31st to suggest exemplary articles on “any and every technology topic–biotech, information technology, gadgetry, tech policy, Silicon Valley, and software engineering” etc.

The 2007 collection is being edited by Clive Thompson. Last year’s was Steven Levy. When complete, the collection is published as a trade paperback and put in its entirety online in clean, fully searchable HTML editions, so head over and help build what will become a terrific open access resource.

Category Archives: publishing

the year of the author

Natalie Merchant, one of my favorite artists, was featured in The New York Times today. She is back after a long hiatus, but if you want to hear her new songs you better stand in line for a ticket to one of her shows because she doesn’t plan to release an album anytime soon. She appeared this weekend at the Hiro Ballroom in New York City. According to the Times, a voice in the crowd asked when Ms. Merchant would release a new album, she said with a smile that she was awaiting “a new paradigm for the recording industry.”

hmm, well, the good news is that the paradigm is shifting, fast. But we don’t yet know if this will be a good thing or a bad thing. It’s certainly a bad thing for the major labels, who are losing market share faster then polar bears are losing their ice (sorry for the awful metaphor). But as they continue to shrink, so do the services and protections they offer to the artists. And the more content moves online the less customers are willing to pay for it. Radiohead’s recent experiment proves that.

But artists are still embracing new media and using it to take matters into their own hands. In the music industry, a long-tail entrepreneurial system supported by online networks and e-commerce is beginning to emerge. Sites like nimbit empower artists to manage their own sales and promotion, bypassing itunes which takes a hefty 50% off the top and and, unlike record labels, does nothing to shape or nurture an artist’s career.

Now, indulge me for a moment while I talk about the Kindle as though it were the ipod of ebooks. It’s not, for lots of reasons. But it does have one thing in common with its music industry counterpart, it allows authors to upload their own content and sell it on amazon. That is huge. That alone might be enough to start a similar paradigm shift in publishing. In this week’s issue of Publisher’s Weekly, Mike Shatzkin predicts it will.

So why have I titled this, “the year of the author”? (I borrowed that phrase from Mike Shatzkin’s prediction #3 btw). I’m not trying to say it will be a great year for authors. New media is going to squeeze them as it is squeezing musicians and striking writer’s guild members. It is the year of the author, because they will be the ones who drive the paradigm shift. They may begin to use online publishing and distribution tools to bypass traditional publishers and put their work out there en masse. OR they will opt out of the internet’s “give-up-your-work-for-free” model and create a new model altogether. Natalie Merchant is opting to (temporarily I hope) bring back the troubadour tradition in the music biz. It will be interesting to see what choices authors make as the publishing industry’s ice begins to shift.

a few rough notes on knols

Think you’ve got an authoritative take on a subject? Write up an article, or “knol,” and see how the Web judgeth. If it’s any good, you might even make a buck.

Google’s new encyclopedia will go head to head with Wikipedia in the search rankings, though in format it more resembles other ad-supported, single-author info sources like the About.com or Squidoo. The knol-verse (how the hell do we speak of these things as a whole?) will be a Darwinian writers’ market where the fittest knols rise to the top. Anyone can write one. Google will host it for free. Multiple knols can compete on a single topic. Readers can respond to and evaluate knols through simple community rating tools. Content belongs solely to the author, who can license it in any way he/she chooses (all rights reserved, Creative Commons, etc.). Authors have the option of having contextual ads run to the side, revenues from which are shared with Google. There is no vetting or editorial input from Google whatsoever.

Except… Might not the ads exert their own subtle editorial influence? In this entrepreneurial writers’ fray, will authors craft their knols for AdSense optimization? Will they become, consciously or not, shills for the companies that place the ads (I’m thinking especially of high impact topic areas like health and medicine)? Whatever you may think of Wikipedia, it has a certain integrity in being ad-free. The mission is clear and direct: to build a comprehensive free encyclopedia for the Web. The range of content has no correlation to marketability or revenue potential. It’s simply a big compendium of stuff, the only mention of money being a frank electronic tip jar at the top of each page. The Googlepedia, in contrast, is fundamentally an advertising platform. What will such an encyclopedia look like?

In the official knol announcement, Udi Manber, a VP for engineering at Google, explains the genesis of the project: “The challenge posed to us by Larry, Sergey and Eric was to find a way to help people share their knowledge. This is our main goal.” You can see embedded in this statement all the trademarks of Google’s rhetoric: a certain false humility, the pose of incorruptible geek integrity and above all, a boundless confidence that every problem, no matter how gray and human, has a technological fix. I’m not saying it’s wrong to build a business, nor that Google is lying whenever it talks about anything idealistic, it’s just that time and again Google displays an astonishing lack of self-awareness in the way it frames its services -? a lack that becomes especially obvious whenever the company edges into content creation and hosting. They tend to talk as though they’re building the library of Alexandria or the great Encyclopédie, but really they’re describing an advanced advertising network of Google-exclusive content. We shouldn’t allow these very different things to become as muddled in our heads as they are in theirs. You get a worrisome sense that, like the Bushies, the cheerful software engineers who promote Google’s products on the company’s various blogs truly believe the things they’re saying. That if we can just get the algorithm right, the world can bask in the light of universal knowledge.

The blogosphere has been alive with commentary about the knol situation throughout the weekend. By far the most provocative thing I’ve read so far is by Anil Dash, VP of Six Apart, the company that makes the Movable Type software that runs this blog. Dash calls out this Google self-awareness gap, or as he puts it, its lack of a “theory of mind”:

Theory of mind is that thing that a two-year-old lacks, which makes her think that covering her eyes means you can’t see her. It’s the thing a chimpanzee has, which makes him hide a banana behind his back, only taking bites when the other chimps aren’t looking.

Theory of mind is the awareness that others are aware, and its absence is the weakness that Google doesn’t know it has. This shortcoming exists at a deep cultural level within the organization, and it keeps manifesting itself in the decisions that the company makes about its products and services. The flaw is one that is perpetuated by insularity, and will only be remedied by becoming more open to outside ideas and more aware of how people outside the company think, work and live.

He gives some examples:

Connecting PageRank to economic systems such as AdWords and AdSense corrupted the meaning and value of links by turning them into an economic exchange. Through the turn of the millennium, hyperlinking on the web was a social, aesthetic, and expressive editorial action. When Google introduced its advertising systems at the same time as it began to dominate the economy around search on the web, it transformed a basic form of online communication, without the permission of the web’s users, and without explaining that choice or offering an option to those users.

He compares the knol enterprise with GBS:

Knol shares with Google Book Search the problem of being both indexed by Google and hosted by Google. This presents inherent conflicts in the ranking of content, as well as disincentives for content creators to control the environment in which their content is published. This necessarily disadvantages competing search engines, but more importantly eliminates the ability for content creators to innovate in the area of content presentation or enhancement. Anything that is written in Knol cannot be presented any better than the best thing in Knol. [his emphasis]

And lastly concludes:

An awareness of the fact that Google has never displayed an ability to create the best tools for sharing knowledge would reveal that it is hubris for Google to think they should be a definitive source for hosting that knowledge. If the desire is to increase knowledge sharing, and the methods of compensation that Google controls include traffic/attention and money/advertising, then a more effective system than Knol would be to algorithmically determine the most valuable and well-presented sources of knowledge, identify the identity of authorites using the same journalistic techniques that the Google News team will have to learn, and then reward those sources with increased traffic, attention and/or monetary compensation.

For a long time Google’s goal was to help direct your attention outward. Increasingly we find that they want to hold onto it. Everyone knows that Wikipedia articles place highly in Google search results. Makes sense then that they want to capture some of those clicks and plug them directly into the Google ad network. But already the Web is dominated by a handful of mega sites. I get nervous at the thought that www.google.com could gradually become an internal directory, that Google could become the alpha and omega, not only the start page of the Internet but all the destinations.

It will be interesting to see just how and to what extent knols start creeping up the search results. Presumably, they will be ranked according to the same secret metrics that measure all pages in Google’s index, but given the opacity of their operations, who’s to say that subtle or unconscious rigging won’t occur? Will community ratings factor in search rankings? That would seem to present a huge conflict of interest. Perhaps top-rated knols will be displayed in the sponsored links area at the top of results pages. Or knols could be listed in order of community ranking on a dedicated knol search portal, providing something analogous to the experience of searching within Wikipedia as opposed to finding articles through external search engines. Returning to the theory of mind question, will Google develop enough awareness of how it is perceived and felt by its users to strike the right balance?

One last thing worth considering about the knol -? apart from its being possibly the worst Internet neologism in recent memory -? is its author-centric nature. It’s interesting that in order to compete with Wikipedia Google has consciously not adopted Wikipedia’s model. The basic unit of authorial action in Wikipedia is the edit. Edits by multiple contributors are combined, through a complicated consensus process, into a single amalgamated product. On Google’s encyclopedia the basic unit is the knol. For each knol (god, it’s hard to keep writing that word) there is a one to one correspondence with an individual, identifiable voice. There may be multiple competing knols, and by extension competing voices (you have this on Wikipedia too, but it’s relegated to the discussion pages).

Viewed in this way, Googlepedia is perhaps a more direct rival to Larry Sanger’s Citizendium, which aims to build a more authoritative Wikipedia-type resource under the supervision of vetted experts. Citizendium is a strange, conflicted experiment, a weird cocktail of Internet populism and ivory tower elitism -? and by the look of it, not going anywhere terribly fast. If knols take off, could they be the final nail in the coffin of Sanger’s awkward dream? Bryan Alexander wonders along similar lines.

While not explicitly employing Sanger’s rhetoric of “expert” review, Google seems to be banking on its commitment to attributed solo authorship and its ad-based incentive system to lure good, knowledgeable authors onto the Web, and to build trust among readers through the brand-name credibility of authorial bylines and brandished credentials. Whether this will work remains to be seen. I wonder… whether this system will really produce quality. Whether there are enough checks and balances. Whether the community rating mechanisms will be meaningful and confidence-inspiring. Whether self-appointed experts will seem authoritative in this context or shabby, second-rate and opportunistic. Whether this will have the feeling of an enlightened knowledge project or of sleezy intellectual link farming (or something perfectly useful in between).

The feel of a site -? the values it exudes -? is an important factor though. This is why I like, and in an odd way trust Wikipedia. Trust not always to be correct, but to be transparent and to wear its flaws on its sleeve, and to be working for a higher aim. Google will probably never inspire that kind of trust in me, certainly not while it persists in its dangerous self-delusions.

A lot of unknowns here. Thoughts?

ghost story

02138, a magazine aimed at Harvard alumni, has a great article about the widespread practice among professors of using low-wage student labor to research and even write their books.

…in any number of academic offices at Harvard, the relationship between “author” and researcher(s) is a distinctly gray area. A young economics professor hires seven researchers, none yet in graduate school, several of them pulling 70-hour work-weeks; historians farm out their research to teams of graduate students, who prepare meticulously written memos that are closely assimilated into the finished work; law school professors “write” books that acknowledge dozens of research assistants without specifying their contributions. These days, it is practically the norm for tenured professors to have research and writing squads working on their publications, quietly employed at stages of co-authorship ranging from the non-controversial (photocopying) to more authorial labor, such as significant research on topics central to the final work, to what can only be called ghostwriting.

Ideally, this would constitute a sort of apprentice system -? one generation of scholars teaching the next through joint endeavor. But in reality the collaborative element, though quietly sanctioned by universities (the article goes into this a bit), receives no direct blessing or stated pedagogical justification. A ghost ensemble works quietly behind the scenes to keep up the appearance of heroic, individual authorship.

cinematic reading

Random House Canada underwrote a series of short videos riffing on Douglas Coupland’s new novel The Gum Thief produced by the slick Toronto studio Crush Inc. These were forwarded to me by Alex Itin, who described watching them as a kind of “cinematic reading.” Watch, you’ll see what he means. There are three basic storylines, each consisting of three clips. This one, from the “Glove Pond” sequence, is particularly clever in its use of old magazines:

All the videos are available here at Crush Inc. Or on Coupland’s YouTube page.

kindle maths 101

Chatting with someone from Random House’s digital division on the day of the Kindle release, I suggested that dramatic price cuts on e-editions -? in other words, finally acknowledging that digital copies aren’t worth as much (especially when they come corseted in DRM) as physical hard copies -? might be the crucial adjustment needed to at last blow open the digital book market. It seemed like a no-brainer to me that Amazon was charging way too much for its e-books (not to mention the Kindle itself). But upon closer inspection, it clearly doesn’t add up that way. Tim O’Reilly explains why:

…the idea that there’s sufficient unmet demand to justify radical price cuts is totally wrongheaded. Unlike music, which is quickly consumed (a song takes 3 to 4 minutes to listen to, and price elasticity does have an impact on whether you try a new song or listen to an old one again), many types of books require a substantial time commitment, and having more books available more cheaply doesn’t mean any more books read. Regular readers already often have huge piles of unread books, as we end up buying more than we have time for. Time, not price, is the limiting factor.

Even assuming the rosiest of scenarios, Kindle readers are going to be a subset of an already limited audience for books. Unless some hitherto untapped reader demographic comes out of the woodwork, gets excited about e-books, buys Kindles, and then significantly surpasses the average human capacity for book consumption, I fail to see how enough books could be sold to recoup costs and still keep prices low. And without lower prices, I don’t see a huge number of people going the Kindle route in the first place. And there’s the rub.

Even if you were to go as far as selling books like songs on iTunes at 99 cents a pop, it seems highly unlikely that people would be induced to buy a significantly greater number of books than they already are. There’s only so much a person can read. The iPod solved a problem for music listeners: carrying around all that music to play on your Disc or Walkman was a major pain. So a hard drive with earphones made a great deal of sense. It shouldn’t be assumed that readers have the same problem (spine-crushing textbook-stuffed backpacks notwithstanding). Do we really need an iPod for books?

UPDATE: Through subsequent discussion both here and off the blog, I’ve since come around 360 back to my original hunch. See comment.

We might, maybe (putting aside for the moment objections to the ultra-proprietary nature of the Kindle), if Amazon were to abandon the per copy idea altogether and go for a subscription model. (I’m just thinking out loud here -? tell me how you’d adjust this.) Let’s say 40 bucks a month for full online access to the entire Amazon digital library, along with every major newspaper, magazine and blog. You’d have the basic cable option: all books accessible and searchable in full, as well as popular feedback functions like reviews and Listmania. If you want to mark a book up, share notes with other readers, clip quotes, save an offline copy, you could go “premium” for a buck or two per title (not unlike the current Upgrade option, although cheaper). Certain blockbuster titles or fancy multimedia pieces (once the Kindle’s screen improves) might be premium access only -? like HBO or Showtime. Amazon could market other services such as book groups, networked classroom editions, book disaggregation for custom assembled print-on-demand editions or course packs.

This approach reconceives books as services, or channels, rather than as objects. The Kindle would be a gateway into a vast library that you can roam about freely, with access not only to books but to all the useful contextual material contributed by readers. Piracy isn’t a problem since the system is totally locked down and you can only access it on a Kindle through Amazon’s Whispernet. Revenues could be shared with publishers proportionately to traffic on individual titles. DRM and all the other insults that go hand in hand with trying to manage digital media like physical objects simply melt away.

* * * * *

On a related note, Nick Carr talks about how the Kindle, despite its many flaws, suggests a post-Web2.0 paradigm for hardware:

If the Kindle is flawed as a window onto literature, it offers a pretty clear view onto the future of appliances. It shows that we’re rapidly approaching the time when centrally stored and managed software and data are seamlessly integrated into consumer appliances – all sorts of appliances.

The problem with “Web 2.0,” as a concept, is that it constrains innovation by perpetuating the assumption that the web is accessed through computing devices, whether PCs or smartphones or game consoles. As broadband, storage, and computing get ever cheaper, that assumption will be rendered obsolete. The internet won’t be so much a destination as a feature, incorporated into all sorts of different goods in all sorts of different ways. The next great wave in internet innovation, in other words, won’t be about creating sites on the World Wide Web; it will be about figuring out creative ways to deploy the capabilities of the World Wide Computer through both traditional and new physical products, with, from the user’s point of view, “no computer or special software required.”

That the Kindle even suggests these ideas signals a major advance over its competitors -? the doomed Sony Reader and the parade of failed devices that came before. What Amazon ought to be shooting for, however, (and almost is) is not an iPod for reading -? a digital knapsack stuffed with individual e-books -? but rather an interface to a networked library.

amazon raises paperback prices

An interesting twist in the Kindle story reported at Dear Author:

Amazon’s pricing for mass market books has suddenly gone full retail, no discount since the release of the Kindle. When questioned in Newsweek about the low pricing, Bezos said “low-margin and high-volume sale – ?you just have to make sure the mix [between discounted and higher-priced items] works.” It looks like Bezos is hoping to make more money off the high volume of sales from those mass market purchasers.

…I guess this is one way of forcing readers to purchase the Kindle. If Kindle success rises or falls on the backs of the mass market purchasers, this is going to be ugly because I see a whole bunch of Amazon purchasers being pretty upset about this turn of events.

Thanks to Peter Brantley for the link.

siva on kindle

Thoughtful comments from Siva Vaidhyanathan on the Kindle:

As far as the dream of textual connectivity and annotations — making books more “Webby” — we don’t need new devices to do that. Nor do we need different social processes. But we do need better copyright laws to facilitate such remixes and critical engagement.

So consider this $400 device from Amazon. Once you drop that cash, you still can’t get books for the $9 cost of writing, editing, and formating. You still pay close to the $30 physical cost that includes all the transportation, warehousing, taxes, returns, and shoplifting built into the price. You can only use Amazon to get texts, thus locking you into a service that might not be best or cheapest. You can only use Sprint to download texts or get Web information. You can’t transfer all you linking and annotating to another machine or network your work. If the DRM fails, you are out of luck. If the device fails, you might not be able to put your library on a new device.

All the highfallutin’ talk about a new way of reading leading to a new way of writing ignores some basic hard problems: the companies involved in this effort do not share goals. And they do not respect readers or writers.

I say we route around them and use these here devices — personal computers — to forge better reading and writing processes.

of razors and blades

A flurry of reactions to the Amazon Kindle release, much of it tipping negative (though interestingly largely by folks who haven’t yet handled the thing).

David Rothman exhaustively covers the DRM/e-book standards angle and is generally displeased:

I think publishers should lay down the law and threaten Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos with slow dismemberment if he fails to promise immediately that the Kindle will do .epub [the International Digital Publishing Forum’s new standard format] in the next six months or so. Epub, epub, epub, Jeff. Publishers still remember how you forced them to abandon PDF in favor of your proprietary Mobi format, at least in Amazon-related deals. You owe ’em one.

Dear Author also laments the DRM situation as well as the jacked-up price:

Here’s the one way I think the Kindle will succeed with consumers (non business consumers). It chooses to employ a subscription program whereby you agree to buy x amount of books at Amazon in exchange for getting the Kindle at some reduced price. Another way to drive ereading traffic to Amazon would be to sell books without DRM. Jeff Bezos was convinced that DRM free music was imperative. Why not DRM free ebooks?

There are also, as of this writing, 128 customer reviews on the actual Amazon site. One of the top-rated ones makes a clever, if obvious, remark on Amazon’s misguided pricing:

The product is interesting but extremely overpriced, especially considering that I still have to pay for books. Amazon needs to discover what Gillette figured out decades ago: Give away the razor, charge for the razor blades. In this model, every Joe gets a razor because he has nothing to lose. Then he discovers that he LOVES the razor, and to continue loving it he needs to buy razors for it. The rest is history.

This e-book device should be almost free, like $30. If that were the case I’d have one tomorrow. Then I’d buy a book for it and see how I like it. If I fall in love with it, then I’ll continue buying books, to Amazon’s benefit.

There is no way I’m taking a chance on a $400 dedicated e-book reader. That puts WAY too much risk on my side of the equation.

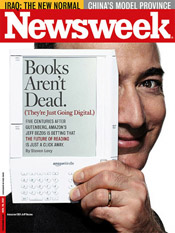

newsweek covers the future of reading

Steven Levy’s Newsweek cover story, “The Future of Reading,” is pegged to the much anticipated release of the Kindle, Amazon’s new e-book reader. While covering a lot of ground, from publishing industry anxieties, to mass digitization, Google, and speculations on longer-term changes to the nature of reading and writing (including a few remarks from us), the bulk of the article is spent pondering the implications of this latest entrant to the charred battlefield of ill-conceived gadgetry which has tried and failed for more than a decade to beat the paper book at its own game. The Kindle has a few very significant new things going for it, mainly an Internet connection and integration with the world’s largest online bookseller, and Jeff Bezos is betting that it might finally strike the balance required to attract larger numbers of readers: doing a respectable job of recreating the print experience while opening up a wide range of digital affordances.

Steven Levy’s Newsweek cover story, “The Future of Reading,” is pegged to the much anticipated release of the Kindle, Amazon’s new e-book reader. While covering a lot of ground, from publishing industry anxieties, to mass digitization, Google, and speculations on longer-term changes to the nature of reading and writing (including a few remarks from us), the bulk of the article is spent pondering the implications of this latest entrant to the charred battlefield of ill-conceived gadgetry which has tried and failed for more than a decade to beat the paper book at its own game. The Kindle has a few very significant new things going for it, mainly an Internet connection and integration with the world’s largest online bookseller, and Jeff Bezos is betting that it might finally strike the balance required to attract larger numbers of readers: doing a respectable job of recreating the print experience while opening up a wide range of digital affordances.

Speaking of that elusive balance, the bit of the article that most stood out for me was this decidely ambivalent passage on losing the “boundedness” of books:

Though the Kindle is at heart a reading machine made by a bookseller – ?and works most impressively when you are buying a book or reading it – ?it is also something more: a perpetually connected Internet device. A few twitches of the fingers and that zoned-in connection between your mind and an author’s machinations can be interrupted – ?or enhanced – ?by an avalanche of data. Therein lies the disruptive nature of the Amazon Kindle. It’s the first “always-on” book.