This time by publishers. Penguin Group USA, McGraw-Hill, Pearson Education, Simon & Schuster and John Wiley & Sons. The gripe is the same as with the Authors’ Guild, which filed suit last month alleging “massive copyright infringement.” Publishers fear a dangerous precedent is set by Google’s scanning of books to construct what amounts to a giant card catalogue on the web. Google claims “fair use” (see rationale), again pointing out that for copyrighted works only tiny “snippets” of text are displayed around keywords (though perhaps this is not yet fully in effect – I was searching around in this book and was able to look at quite a lot).

Google calls the publishers’ suit “near-sighted.” And it probably is. The benefit to readers and researchers will be tremendous, as will (Google is eager to point out) the exposure for authors and publishers. But Google Print is undoubtedly an earth-shaking program. Look at the reaction in Europe, where alarm bells rung by France warned of cultural imperialism, an english-drenched web. Heads of state and culture convened and initial plans for a European digital library have been drawn up.

What the transatlantic flap makes clear is that Google’s book scanning touches a deep nerve, and the argument over intellectual property, signficant though it is, distracts from a more profound human anxiety — an anxiety about the form of culture and the shape of thoughts. If we try to grope back through the millennia, we can find find an analogy in the invention of writing.

The shift from oral to written language froze speech into stable strings that could be transmitted and stored over distance and time. This change not only affected the modes of communication, it dramatically refigured the cognitive makeup of human beings (as McLuhan, Ong and others have described). We are currently going through another such shift. The digital takes the freezing medium of text and throws it back into fluidity. Like the melting of polar ice caps, it unsettles equilibriums, changes weather patterns. It is a lot to adjust to, and we wonder if our great-great-grandchildren will literally think differently from us.

But in spite of this disorienting new fluidity, we still have print, we still have the book. And actually, Google Print in many ways affirms this since its search returns will point to print retailers and brick-and-mortar libraries. Yet the fact remains that the canon is being scanned, with implications we can’t fully perceive, and future uses we can’t fully predict, and so it is understandable that many are unnerved. The ice is really beginning to melt.

In Phaedrus, Plato expresses a similar anxiety about the invention of writing. He tells the tale of Theuth, an Egyptian deity who goes around spreading the new technology, and one day encounters a skeptic in King Thamus:

…you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a power opposite to that which they in fact possess. For this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it; they will not exercise their memories, but, trusting in external, foreign marks, they will not bring things to remembrance from within themselves. You have discovered a remedy not for memory, but for reminding. You offer your students the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom. They will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.

As I type, I’m exhibiting wisdom without the reality. I’ve read Plato, but nowhere near exhaustively. Yet I can slash and weave texts on the web in seconds, throw together a blog entry and send it screeching into the commons. And with Google Print I can get the quote I need and let the rest of the book rot behind the security fence. This fluidity is dangerous because it makes connections so easy. Do we know what we are connecting?

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year). Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public

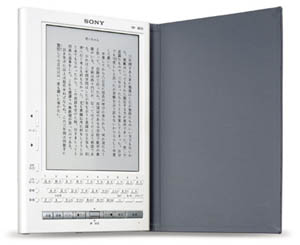

As for the device, well, the

As for the device, well, the