Scott McLemee has made an interesting proposal for a scholarly aggregator site that would weave together material from academic blogs and university presses. Initially, this would resemble an enhanced academic blogroll, building on existing efforts such as those at Crooked Timber and Cliopatria, but McLemee envisions it eventually growing into a full-fledged discourse network, with book reviews, symposia, a specialized search engine, and a peer voting system á la Digg.

This all bears significant resemblance to some of the ideas that emerged from a small academic blogging symposium that the Institute held last November to brainstorm ways to leverage scholarly blogging, and to encourage more professors to step out of the confines of the academy into the role of public intellectual. Some of those ideas are set down here, on a blog we used for planning the meeting. Also take a look at John Holbo’s proposal for an academic blog collective, or co-op. Also note the various blog carnivals around the web, which practice a simple but effective form of community aggregation and review. One commenter on McLemee’s article points to a science blog aggregator site called Postgenomic, which offers a similar range of services, as well as providing useful meta-analysis of trends across the science blogosphere — i.e. what are the most discussed journal papers, news stories, and topics.

For any enterprise of this kind, where the goal is to pull together an enormous number of strands into a coherent whole, the role of the editor is crucial. Yet, at a time when self-publishing is the becoming the modus operandi for anyone who would seek to maintain a piece of intellectual turf in the network culture, the editor’s task is less to solicit or vet new work, and more to moderate the vast conversation that is already occurring — to listen to what the collective is saying, and also to draw connections that the collective, in their bloggers’ trenches, may have missed.

Since that November meeting, our thinking has broadened to include not just blogging, but all forms of academic publishing. On Monday, we’ll post an introduction to a project we’re cooking up for an online scholarly network in the field of media studies. Stay tuned.

Category Archives: publishing

rice university press reborn digital

After lying dormant for ten years, Rice University Press has relaunched, reconstituting itself as a fully digital operation centered around Connexions, an open-access repository of learning modules, course guides and authoring tools.  Connexions was started at Rice in 1999 by Richard Baraniuk, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and has since grown into one of the leading sources of open educational content — also an early mover into the Creative Commons movement, building flexible licensing into its publishing platform and allowing teachers and students to produce derivative materials and customized textbooks from the array of resources available on the site.

Connexions was started at Rice in 1999 by Richard Baraniuk, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and has since grown into one of the leading sources of open educational content — also an early mover into the Creative Commons movement, building flexible licensing into its publishing platform and allowing teachers and students to produce derivative materials and customized textbooks from the array of resources available on the site.

The new ingredient in this mix is a print-on-demand option through a company called QOOP. Students can order paper or hard-bound copies of learning modules for a fraction of the cost of commercial textbooks, even used ones. There are also some inexpensive download options. Web access, however, is free to all. Moreover, Connexions authors can update and amend their modules at all times. The project is billed as “open source” but individual authorship is still the main paradigm. The print-on-demand and for-pay download schemes may even generate small royalties for some authors.

The Wall Street Journal reports. You can also read these two press releases from Rice:

“Rice University Press reborn as nation’s first fully digital academic press”

“Print deal makes Connexions leading open-source publisher”

UPDATE:

Kathleen Fitzpatrick makes the point I didn’t have time to make when I posted this:

Rice plans, however, to “solicit and edit manuscripts the old-fashioned way,” which strikes me as a very cautious maneuver, one that suggests that the change of venue involved in moving the press online may not be enough to really revolutionize academic publishing. After all, if Rice UP was crushed by its financial losses last time around, can the same basic structure–except with far shorter print runs–save it this time out?

I’m excited to see what Rice produces, and quite hopeful that other university presses will follow in their footsteps. I still believe, however, that it’s going to take a much riskier, much more radical revisioning of what scholarly publishing is all about in order to keep such presses alive in the years to come.

GAM3R 7H30RY gets (open) peer-reviewed

Steven Shaviro (of Wayne State University) has written a terrific review of GAM3R 7H30RY on his blog, The Pinnochio Theory, enacting what can only be described as spontaneous, open peer review. This is the first major article to seriously engage with the ideas and arguments of the book itself, rather than the more general story of Wark’s experiment with open, collaborative publishing (for example, see here and here). Anyone looking for a good encapsulation of McKenzie’s ideas would do well to read this. Here, as a taste, is Shaviro’s explanation of “a world…made over as an imperfect copy of the game“:

Computer games clarify the inner logic of social control at work in the world. Games give an outline of what actually happens in much messier and less totalized ways. Thereby, however, games point up the ways in which social control is precisely directed towards creating game-like clarities and firm outlines, at the expense of our freedoms.

Now, I think it’s worth pointing out the one gap in this otherwise exceptional piece. That is that, while exhibiting acute insight into the book’s theoretical dimensions, Shaviro does not discuss the form in which these theories are delivered, apart from brief mention of the numbered paragraph scheme and the alphabetically ordered chapter titles. Though he does link to the website, at no point does he mention the open web format and the reader discussion areas, nor the fact that he read the book online, with the comments of readers sitting plainly in the margins. If you were to read only this review, you would assume Shaviro was referring to a vetted, published book from a university press, when actually he is discussing a networked book that is 1.1 — a.k.a. still in development. Shaviro treats the text as though it is fully cooked (naturally, this is how we are used to dealing with scholarly works). But what happens when there’s a GAM3R 7H30RY 1.2, or a 2.0? Will Shaviro’s review correspondingly update? Does an open-ended book require a more open-ended critique? This is not so much a criticism of Shaviro as an observation of a tricky problem yet to be solved.

Regardless, this a valuable contribution to the surrounding literature. It’s very exciting to see leading scholars building a discourse outside the conventional publishing channels: Wark, through his pre-publication with the Institute, and Shaviro with his unsolicited blog review. This is an excellent sign.

the myth of universal knowledge 2: hyper-nodes and one-way flows

My post a couple of weeks ago about Jean-Noël Jeanneney’s soon-to-be-released anti-Google polemic sparked a discussion here about the cultural trade deficit and the linguistic diversity (or lack thereof) of digital collections. Around that time, Rüdiger Wischenbart, a German journalist/consultant, made some insightful observations on precisely this issue in an inaugural address to the 2006 International Conference on the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage in Salzburg. His discussion is framed provocatively in terms of information flow, painting a picture of a kind of fluid dynamics of global culture, in which volume and directionality are the key indicators of power.

My post a couple of weeks ago about Jean-Noël Jeanneney’s soon-to-be-released anti-Google polemic sparked a discussion here about the cultural trade deficit and the linguistic diversity (or lack thereof) of digital collections. Around that time, Rüdiger Wischenbart, a German journalist/consultant, made some insightful observations on precisely this issue in an inaugural address to the 2006 International Conference on the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage in Salzburg. His discussion is framed provocatively in terms of information flow, painting a picture of a kind of fluid dynamics of global culture, in which volume and directionality are the key indicators of power.

First, he takes us on a quick tour of the print book trade, pointing out the various roadblocks and one-way streets that skew the global mind map. A cursory analysis reveals, not surprisingly, that the international publishing industry is locked in a one-way flow maximally favoring the West, and, moreover, that present digitization efforts, far from ushering in a utopia of cultural equality, are on track to replicate this.

…the market for knowledge is substantially controlled by the G7 nations, that is to say, the large economic powers (the USA, Canada, the larger European nations and Japan), while the rest of the world plays a subordinate role as purchaser.

Foreign language translation is the most obvious arena in which to observe the imbalance. We find that the translation of literature flows disproportionately downhill from Anglophone heights — the further from the peak, the harder it is for knowledge to climb out of its local niche. Wischenbart:

An already somewhat obsolete UNESCO statistic, one drawn from its World Culture Report of 2002, reckons that around one half of all translated books worldwide are based on English-language originals. And a recent assessment for France, which covers the year 2005, shows that 58 percent of all translations are from English originals. Traditionally, German and French originals account for an additional one quarter of the total. Yet only 3 percent of all translations, conversely, are from other languages into English.

…When it comes to book publishing, in short, the transfer of cultural knowledge consists of a network of one-way streets, detours, and barred routes.

…The central problem in this context is not the purported Americanization of knowledge or culture, but instead the vertical cascade of knowledge flows and cultural exports, characterized by a clear power hierarchy dominated by larger units in relation to smaller subordinated ones, as well as a scarcity of lateral connections.

Turning his attention to the digital landscape, Wischenbart sees the potential for “new forms of knowledge power,” but quickly sobers us up with a look at the way decentralized networks often still tend toward consolidation:

Previously, of course, large numbers of books have been accessible in large libraries, with older books imposing their contexts on each new release. The network of contents encompassing book knowledge is as old as the book itself. But direct access to the enormous and constantly growing abundance of information and contents via the new information and communication technologies shapes new knowledge landscapes and even allows new forms of knowledge power to emerge.

Theorists of networks like Albert-Laszlo Barabasi have demonstrated impressively how nodes of information do not form a balanced, level field. The more strongly they are linked, the more they tend to constitute just a few outstandingly prominent nodes where a substantial portion of the total information flow is bundled together. The result is the radical antithesis of visions of an egalitarian cyberspace.

He then trains his sights on the “long tail,” that egalitarian business meme propogated by Chris Anderson’s new book, which posits that the new information economy will be as kind, if not kinder, to small niche markets as to big blockbusters. Wischenbart is not so sure:

He then trains his sights on the “long tail,” that egalitarian business meme propogated by Chris Anderson’s new book, which posits that the new information economy will be as kind, if not kinder, to small niche markets as to big blockbusters. Wischenbart is not so sure:

…there exists a massive problem in both the structure and economics of cultural linkage and transfer, in the cultural networks existing beyond the powerful nodes, beyond the high peaks of the bestseller lists. To be sure, the diversity found below the elongated, flattened curve does constitute, in the aggregate, approximately one half of the total market. But despite this, individual authors, niche publishing houses, translators and intermediaries are barely compensated for their services. Of course, these multifarious works are produced, and they are sought out and consumed by their respective publics. But the “long tail” fails to gain a foothold in the economy of cultural markets, only to become – as in the 18th century – the province of the amateur. Such is the danger when our attention is drawn exclusively to dominant productions, and away from the less surveyable domains of cultural and knowledge associations.

John Cassidy states it more tidily in the latest New Yorker:

There’s another blind spot in Anderson’s analysis. The long tail has meant that online commerce is being dominated by just a few businesses — mega-sites that can house those long tails. Even as Anderson speaks of plentitude and proliferation, you’ll notice that he keeps returning for his examples to a handful of sites — iTunes, eBay, Amazon, Netflix, MySpace. The successful long-tail aggregators can pretty much be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Many have lamented the shift in publishing toward mega-conglomerates, homogenization and an unfortunate infatuation with blockbusters. Many among the lamenters look to the Internet, and hopeful paradigms like the long tail, to shake things back into diversity. But are the publishing conglomerates of the 20th century simply being replaced by the new Internet hyper-nodes of the 21st? Does Google open up more “lateral connections” than Bertelsmann, or does it simply re-aggregate and propogate the existing inequities? Wischenbart suspects the latter, and cautions those like Jeanneney who would seek to compete in the same mode:

If, when breaking into the digital knowledge society, European initiatives (for instance regarding the digitalization of books) develop positions designed to counteract the hegemonic status of a small number of monopolistic protagonists, then it cannot possibly suffice to set a corresponding European pendant alongside existing “hyper nodes” such as Amazon and Google. We have seen this already quite clearly with reference to the publishing market: the fact that so many globally leading houses are solidly based in Europe does nothing to correct the prevailing disequilibrium between cultures.

dark waters? scholarly presses tread along…

Recently in New Orleans, I was working at AAUP‘s annual meeting of university presses. At the opening banquet, Times-Picayune editor Jim Amoss brought a large audience of publishing folk through a blow-by-blow of New Orleans’ storm last fall. What I found particularly resonant in his recount, beyond his staff’s stamina in the face of “the big one”, was the Big Bang phenomena that occured in tandem with the flooding, instantly expanding the relationship between their print and internet editions.

Their print infrastructure wrecked, The Times-Picayune immediately turned to the internet to broadcast the crisis that was flooding in around them. Even the more troglodytic staffers familiarized themselves with blogging and online publishing. By the time some of their print had arrived from offsite and reporters were using it as currency to get through military checkpoints, their staff had adapted to web publishing technologies and now, Amoss told me, they all use it on a daily basis.

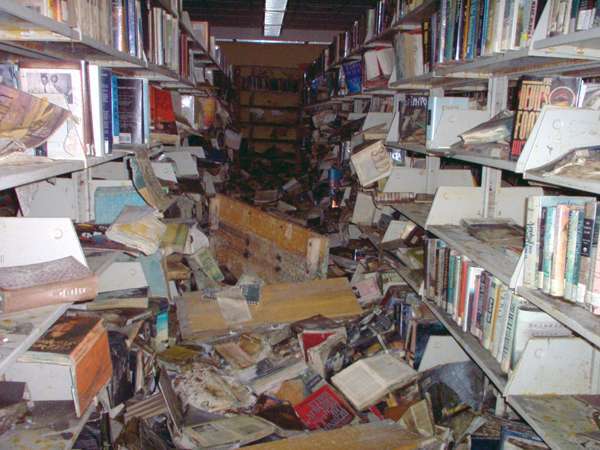

Martin Luther King Branch

If the Times-Picayune, a daily publication of considerable city-paper bulk, can adapt within a week to the web, what is taking university presses so long? Surely, we shouldn’t wait for a crisis of Noah’s Ark proportions to push academe to leap into the future present. What I think Amoss’s talk subtly arrived at was a reassessment of *crisis* for the constituency of scholarly publishing that sat before him.

“Part of the problem is that much of this new technology wasn’t developed within the publishing houses,” a director mentioned to me in response to my wonderings. “So there’s a general feeling of this technology pushing in on the presses from the outside.”

East New Orleans Regional Branch

But “general feeling” belies what were substantially disparate opinions among attendees. Frustration emanated from the more tech-adventurous on the failure of traditional and un-tech’d folks to “get with the program,” whereas those unschooled on wikis and Web 2.0 tried to wrap their brains around the publishing “crisis” as they saw it: outdating their business models, scrambling their workflow charts and threatening to render their print operations obsolete.

That said, cutting through this noise were some promising talks on developments. A handful of presses have established e-publishing initiatives, many of which were conceived of with their university libraries. By piggybacking on the techno-knowledge and skill of librarians who are already digitizing their collections and acquiring digital titles (librarians whose acquisitions budgets far surpass those of many university presses,) presses have brought forth inventive virtual nodes of scholarship. Interestingly, these joint digital endeavors often explore disciplines that now have difficulty making their way to print.

Some projects to look at:

MITH (Maryland); NINES (scholar driven open-access project); Martha Nell Smith’s Dickinson Electronic Archives Project; Rotunda (Virginia); DART (Columbia); Anthrosource (California: Their member portal has communities of interest establishing in various fields, which may evolve into new journals.)

East New Orleans Regional Branch

While the marriage of the university library and press serves to reify their shared mandate to disseminate scholarship, compatibility issues arise in the accessibility and custody of projects. Libraries would like content to be open, and university presses prefer to focus on revenue generating subscribership.

One Digital Publishing session shed light on more theoretical concerns of presses. As MLA reviews the tenure system, partly in response to the decline of monograph publication opportunities, some argued that the nature of the monograph (sustained argument and narrative) doesn’t lend itself well to online reading. But, as the monograph will stay, how do presses publish them economically?

Nora Navra Branch

On the peer review front, another concern critiqued the web’s predominantly fact-based interaction: “The web seems to be pushing us back from an emphasis on ideas and synthesis/analysis to focus on facts.”

Access to facts opens up opportunities for creative presentation of information, but scholarly presses are struggling with how interpretive work can be built on that digitally. A UVA respondant noted, “Librarians say people are looking for info on the web, but then moving to print for the interpretation; at Rotunda, the experience is that you have to put up the mass of information allowing the user to find the raw information, but what to do next is lacking online.”

Promising comments came from Peter Brantley (California Digital Library) on the journal side: peer review isn’t everything and avenues already exist to evaluate content and comment on work (linkages, citation analysis, etc.) To my relief, he suggested folks look at the Institute for the Future of the Book, who are exploring new forms of narrative and participatory material, and Nature’s experiments in peer review.

Sure, at this point, there lacks a concrete theoretical underpinning of how the Internet should provide information, and which kinds. But most of us view this flux as its strength. For university presses, crises arise when what scholar Martha Nell Smith dubs the “priestly voice” of scholarship and authoritative texts, is challenged. Fortifying against the evolution and burgeoning pluralism won’t work. Unstifled, collaborative exploration amongst a range of key players will reveal the possiblities of the terrain, and ease the press out of rising waters.

Robert E. Smith Regional Branch

All images from New Orleans Public Library

on the future of peer review in electronic scholarly publishing

Over the last several months, as I’ve met with the folks from if:book and with the quite impressive group of academics we pulled together to discuss the possibility of starting an all-electronic scholarly press, I’ve spent an awful lot of time thinking and talking about peer review — how it currently functions, why we need it, and how it might be improved. Peer review is extremely important — I want to acknowledge that right up front — but it threatens to become the axle around which all conversations about the future of publishing get wrapped, like Isadora Duncan’s scarf, strangling any possible innovations in scholarly communication before they can get launched. In order to move forward with any kind of innovative publishing process, we must solve the peer review problem, but in order to do so, we first have to separate the structure of peer review from the purposes it serves — and we need to be a bit brutally honest with ourselves about those purposes, distinguishing between those purposes we’d ideally like peer review to serve and those functions it actually winds up fulfilling.

The issue of peer review has of course been brought back to the front of my consciousness by the experiment with open peer review currently being undertaken by the journal Nature, as well as by the debate about the future of peer review that the journal is currently hosting (both introduced last week here on if:book). The experiment is fairly simple: the editors of Nature have created an online open review system that will run parallel to its traditional anonymous review process.

From 5 June 2006, authors may opt to have their submitted manuscripts posted publicly for comment.

Any scientist may then post comments, provided they identify themselves. Once the usual confidential peer review process is complete, the public ‘open peer review’ process will be closed. Editors will then read all comments on the manuscript and invite authors to respond. At the end of the process, as part of the trial, editors will assess the value of the public comments.

As several entries in the web debate that is running alongside this trial make clear, though, this is not exactly a groundbreaking model; the editors of several other scientific journals that already use open review systems to varying extents have posted brief comments about their processes. Electronic Transactions in Artificial Intelligence, for instance, has a two-stage process, a three-month open review stage, followed by a speedy up-or-down refereeing stage (with some time for revisions, if desired, inbetween). This process, the editors acknowledge, has produced some complications in the notion of “publication,” as the texts in the open review stage are already freely available online; in some sense, the journal itself has become a vehicle for re-publishing selected articles.

Peer review is, by this model, designed to serve two different purposes — first, fostering discussion and feedback amongst scholars, with the aim of strengthening the work that they produce; second, filtering that work for quality, such that only the best is selected for final “publication.” ETAI’s dual-stage process makes this bifurcation in the purpose of peer review clear, and manages to serve both functions well. Moreover, by foregrounding the open stage of peer review — by considering an article “published” during the three months of its open review, but then only “refereed” once anonymous scientists have held their up-or-down vote, a vote that comes only after the article has been read, discussed, and revised — this kind of process seems to return the center of gravity in peer review to communication amongst peers.

I wonder, then, about the relatively conservative move that Nature has made with its open peer review trial. First, the journal is at great pains to reassure authors and readers that traditional, anonymous peer review will still take place alongside open discussion. Beyond this, however, there seems to be a relative lack of communication between those two forms of review: open review will take place at the same time as anonymous review, rather than as a preliminary phase, preventing authors from putting the public comments they receive to use in revision; and while the editors will “read” all such public comments, it appears that only the anonymous reviews will be considered in determining whether any given article is published. Is this caution about open review an attempt to avoid throwing out the baby of quality control with the bathwater of anonymity? In fact, the editors of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics present evidence (based on their two-stage review process) that open review significantly increases the quality of articles a journal publishes:

Our statistics confirm that collaborative peer review facilitates and enhances quality assurance. The journal has a relatively low overall rejection rate of less than 20%, but only three years after its launch the ISI journal impact factor ranked Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics twelfth out of 169 journals in ‘Meteorology and Atmospheric Sciences’ and ‘Environmental Sciences’.

These numbers support the idea that public peer review and interactive discussion deter authors from submitting low-quality manuscripts, and thus relieve editors and reviewers from spending too much time on deficient submissions.

By keeping anonymous review and open review separate, without allowing the open any precedence, Nature is allowing itself to avoid asking any risky questions about the purposes of its process, and is perhaps inadvertently maintaining the focus on peer review’s gatekeeping function. The result of such a focus is that scholars are less able to learn from the review process, less able to put comments on their work to use, and less able to respond to those comments in kind.

If anonymous, closed peer review processes aren’t facilitating scholarly discourse, what purposes do they serve? Gatekeeping, as I’ve suggested, is a primary one; as almost all of the folks I’ve talked with this spring have insisted, peer review is necessary to ensuring that the work published by scholarly outlets is of sufficiently high quality, and anonymity is necessary in order to allow reviewers the freedom to say that an article should not be published. In fact, this question of anonymity is quite fraught for most of the academics with whom I’ve spoken; they have repeatedly responded with various degrees of alarm to suggestions that their review comments might in fact be more productive delivered publicly, as part of an ongoing conversation with the author, rather than as a backchannel, one-way communication mediated by an editor. Such a position may be justifiable if, again, the primary purpose of peer review is quality control, and if the process is reliably scrupulous. However, as other discussants in the Nature web debate point out, blind peer review is not a perfect process, subject as it is to all kinds of failures and abuses, ranging from flawed articles that nonetheless make it through the system to ideas that are appropriated by unethical reviewers, with all manner of cronyism and professional jealousy inbetween.

So, again, if closed peer review processes aren’t serving scholars in their need for feedback and discussion, and if they can’t be wholly relied upon for their quality-control functions, what’s left? I’d argue that the primary purpose that anonymous peer review actually serves today, at least in the humanities (and that qualifier, and everything that follows from it, opens a whole other can of worms that needs further discussion — what are the different needs with respect to peer review in the different disciplines?), is that of institutional warranting, of conveying to college and university administrations that the work their employees are doing is appropriate and well-thought-of in its field, and thus that these employees are deserving of ongoing appointments, tenure, promotions, raises, and whathaveyou.

Are these the functions that we really want peer review to serve? Vast amounts of scholars’ time is poured into the peer review process each year; wouldn’t it be better to put that time into open discussions that not only improve the individual texts under review but are also, potentially, productive of new work? Isn’t it possible that scholars would all be better served by separating the question of credentialing from the publishing process, by allowing everything through the gate, by designing a post-publication peer review process that focuses on how a scholarly text should be received rather than whether it should be out there in the first place? Would the various credentialing bodies that currently rely on peer review’s gatekeeping function be satisfied if we were to say to them, “no, anonymous reviewers did not determine whether my article was worthy of publication, but if you look at the comments that my article has received, you can see that ten of the top experts in my field had really positive, constructive things to say about it”?

Nature‘s experiment is an honorable one, and a step in the right direction. It is, however, a conservative step, one that foregrounds the institutional purposes of peer review rather than the ways that such review might be made to better serve the scholarly community. We’ve been working this spring on what we imagine to be a more progressive possibility, the scholarly press reimagined not as a disseminator of discrete electronic texts, but instead as a network that brings scholars together, allowing them to publish everything from blogs to books in formats that allow for productive connections, discussions, and discoveries. I’ll be writing more about this network soon; in the meantime, however, if we really want to energize scholarly discourse through this new mode of networked publishing, we’re going to have to design, from the ground up, a productive new peer review process, one that makes more fruitful interaction among authors and readers a primary goal.

nature re-jiggers peer review

Nature, one of the most esteemed arbiters of scientific research, has initiated a major experiment that could, if successful, fundamentally alter the way it handles peer review, and, in the long run, redefine what it means to be a scholarly journal. From the editors:

…like any process, peer review requires occasional scrutiny and assessement. Has the Internet bought new opportunities for journals to manage peer review more imaginatively or by different means? Are there any systematic flaws in the process? Should the process be transparent or confidential? Is the journal even necessary, or could scientists manage the peer review process themselves?

Nature’s peer review process has been maintained, unchanged, for decades. We, the editors, believe that the process functions well, by and large. But, in the spirit of being open to considering alternative approaches, we are taking two initiatives: a web debate and a trial of a particular type of open peer review.

The trial will not displace Nature’s traditional confidential peer review process, but will complement it. From 5 June 2006, authors may opt to have their submitted manuscripts posted publicly for comment.

In a way, Nature’s peer review trial is nothing new. Since the early days of the Internet, the scientific community has been finding ways to share research outside of the official publishing channels — the World Wide Web was created at a particle physics lab in Switzerland for the purpose of facilitating exchange among scientists. Of more direct concern to journal editors are initiatives like PLoS (Public Library of Science), a nonprofit, open-access publishing network founded expressly to undercut the hegemony of subscription-only journals in the medical sciences. More relevant to the issue of peer review is a project like arXiv.org, a “preprint” server hosted at Cornell, where for a decade scientists have circulated working papers in physics, mathematics, computer science and quantitative biology. Increasingly, scientists are posting to arXiv before submitting to journals, either to get some feedback, or, out of a competitive impulse, to quickly attach their names to a hot idea while waiting for the much slower and non-transparent review process at the journals to unfold. Even journalists covering the sciences are turning more and more to these preprint sites to scoop the latest breakthroughs.

Nature has taken the arXiv model and situated it within a more traditional editorial structure. Abstracts of papers submitted into Nature’s open peer review are immediately posted in a blog, from which anyone can download a full copy. Comments may then be submitted by any scientist in a relevant field, provided that they submit their name and an institutional email address. Once approved by the editors, comments are posted on the site, with RSS feeds available for individual comment streams. This all takes place alongside Nature’s established peer review process, which, when completed for a particular paper, will mean a freeze on that paper’s comments in the open review. At the end of the three-month trial, Nature will evaluate the public comments and publish its conclusions about the experiment.

A watershed moment in the evolution of academic publishing or simply a token gesture in the face of unstoppable change? We’ll have to wait and see. Obviously, Nature’s editors have read the writing on the wall: grasped that the locus of scientific discourse is shifting from the pages of journals to a broader online conversation. In attempting this experiment, Nature is saying that it would like to host that conversation, and at the same time suggesting that there’s still a crucial role to be played by the editor, even if that role increasingly (as we’ve found with GAM3R 7H30RY) is that of moderator. The experiment’s success will ultimately hinge on how much the scientific community buys into this kind of moderated semi-openness, and on how much control Nature is really willing to cede to the community. As of this writing, there are only a few comments on the open papers.

Accompanying the peer review trial, Nature is hosting a “web debate” (actually, more of an essay series) that brings together prominent scientists and editors to publicly examine the various dimensions of peer review: what works, what doesn’t, and what might be changed to better harness new communication technologies. It’s sort of a peer review of peer review. Hopefully this will occasion some serious discussion, not just in the sciences, but across academia, of how the peer review process might be re-thought in the context of networks to better serve scholars and the public.

(This is particularly exciting news for the Institute, since we are currently working to effect similar change in the humanities. We’ll talk more about that soon.)

more evidence of academic publishing being broken

Stay Free! Daily reprints an article from the Wall Street Journal on how the editors of scientific journals published by Thomson Scientific are coercing authors to include more citations to articles published by Thomson Scientific:

Dr. West, the Distinguished Professor of Medicine and Physiology at the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, is one of the world’s leading authorities on respiratory physiology and was a member of Sir Edmund Hillary’s 1960 expedition to the Himalayas. After he submitted a paper on the design of the human lung to the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, an editor emailed him that the paper was basically fine. There was just one thing: Dr. West should cite more studies that had appeared in the respiratory journal.

If that seems like a surprising request, in the world of scientific publishing it no longer is. Scientists and editors say scientific journals increasingly are manipulating rankings — called “impact factors” — that are based on how often papers they publish are cited by other researchers.

“I was appalled,” says Dr. West of the request. “This was a clear abuse of the system because they were trying to rig their impact factor.”

Read the full article here.

in publishers weekly…

We’ve got a column in the latest Publishers Weekly. An appeal to publishers to start thinking about books in a network context.

on ebay: collaborative fiction, one page at a time

Phil McArthur is not a writer. But while recovering from a recent fight with cancer, he began to dream about producing a novel. Sci-fi or horror most likely — the kind of stuff he enjoys to read. But what if he could write it socially? That is, with other people? What if he could send the book spinning like a top and just watch it go?

Say he pens the first page of what will eventually become a 250-page thriller and then passes the baton to a stranger. That person goes on to write the second page, then passes it on again to a third author. And a fourth. A fifth. And so on. One page per day, all the way to 250. By that point it’s 2007 and they can publish the whole thing on Lulu.

The fruit of these musings is (or will be… or is steadily becoming) “Novel Twists”, a ongoing collaborative fiction experiment where you, I or anyone can contribute a page. The only stipulations are that entries are between 250 and 450 words, are kept reasonably clean, and that you refrain from killing the protagonist, Andy Amaratha — at least at this early stage, when only 17 pages have been completed. Writers also get a little 100-word notepad beneath their page to provide a biographical sketch and author’s notes. Once they’ve published their slice, the subsequent page is auctioned on Ebay. Before too long, a final bid is accepted and the next appointed author has 24 hours to complete his or her page.

Networked vanity publishing, you might say. And it is. But McArthur clearly isn’t in it for the money: bids are made by the penny, and all proceeds go to a cancer charity. The Ebay part is intended more to boost the project’s visibility (an article in yesterday’s Guardian also helps), and “to allow everyone a fair chance at the next page.” The main point is to have fun, and to test the hunch that relay-race writing might yield good fiction. In the end, McArthur seems not to care whether it does or not, he just wants to see if the thing actually can get written.

Surrealists explored this territory in the 1920s with the “exquisite corpse,” a game in which images and texts are assembled collaboratively, with knowledge of previous entries deliberately obscured. This made its way into all sorts of games we played when we were young and books that we read (I remember that book of three-panel figures where heads, midriffs and legs could be endlessly recombined to form hilarious, fantastical creatures). The internet lends itself particularly well to this kind of playful medley.