What to say about this thing? After multiple delays, it’s finally out, and in time for the holidays. David Rothman, as usual, has provided exhaustive and entertaining coverage over at Teleread (here, here and here), and points to noteworthy reviews elsewhere.

What to say about this thing? After multiple delays, it’s finally out, and in time for the holidays. David Rothman, as usual, has provided exhaustive and entertaining coverage over at Teleread (here, here and here), and points to noteworthy reviews elsewhere.

It’s no secret that our focus here at the Institute isn’t on the kind of ebooks that simply transfer printed texts to the screen. We’re much more interested in the new kinds of reading and writing that become possible in a digital, network environment. But even measuring Sony’s new device against its own rather pedestrian goals — replicating the print reading experience for the screen with digital enhancements — I still have to say that the Reader fails. Here are the main reasons why:

1) Replicating the print reading experience?

E-ink is definitely different than reading off of an LCD screen. The page looks much more organic and is very gentle on the eyes, though the resolution is still nowhere near that of ink on paper. Still, e-ink is undeniably an advance and it’s exciting to imagine where it might lead.

Other elements of print reading are conjured less successfully, most significantly, the book as a “random access” medium. Random access means that the reader has control over their place in the book, and over the rate and direction at which they move through it. The Sony Reader greatly diminishes this control. Though it does allow you to leave bookmarks, it’s very difficult to jump from place to place unless those places have been intentionally marked. The numbered buttons (1 through 10) directly below the screen offer offer only the crudest browsing capability, allowing you to jump 10, 20, 30 percent etc. through the text.

Another thing affecting readability is that action of flipping pages is slowed down significantly by the rearrangement of the e-ink particles, producing a brief but disorienting flash every time you change your place. Another important element of print reading is the ability to make annotations, and on the Sony Reader this is disabled entirely. In fact, there are no inputs on the device at all — no keyboard, no stylus — apart from the basic navigation buttons. So, to sum up, the Sony Reader is really only intended for straight-ahead reading. Browsing, flipping and note-taking, which, if you ask me, are pretty important parts of reading a book, are disadvantaged.

2) Digital enhancements?

Ok, so the Sony Reader doesn’t do such a great job at replicating print reading, but the benefits of having your books in digital form more than make up for that, right? Sadly, wrong. The most obvious advantage of going digital is storage capacity, the ability to store an entire library on a single device. But the Sony Reader comes with a piddling 64 megabytes of memory. 64! It seems a manufacturer would have to go out of its way these days to make a card that small. The new iPod Shuffle is barely bigger than a quarter and they start at one gigabyte. Sony says that 64 MB will store approximately 80 books, but throw a few images and audio files in there, and this will dramatically decrease.

So, storage stinks, but electronic text has other advantages. Searchability, for example. True! But the Sony Reader software doesn’t allow you to search texts (!!!). I’d guess that this is due to the afore-mentioned time lags of turning pages in e-ink, and how that would slow down browsing through search results. And again, there’s the matter of no inputs — keyboard or stylus — to enter the search queries in the first place.

Fine. Then how about internet connectivity? Sorry. There’s none. Well then what about pulling syndicated content from the web for offline reading, i.e. RSS? You can do this, but only barely. Right now on the Sony Connect store, there are feeds available from about ten popular blogs and news sources. Why so few? Well, they plan to expand that soon, but apparently there are tricky issues with reformatting the feeds for the Reader, so they’re building up this service piecemeal, without letting web publishers post their feeds directly. Last night, I attended a press event that Sony held at the W Hotel at Union Square, NYC, where I got to play around with one of the devices hooked up to the online store. I loaded a couple of news feeds onto my Reader and took a look. Pretty ghastly. Everything is dumped into one big, barely formatted file, where it’s not terribly clear where one entry ends and another begins. Unrendered characters float here and there. They’ve got a long way to go on this one.

Which leads us to the fundamental problem with the Sony Reader, or with any roughly equivalent specialized e-reading device: the system is proprietary. Read David Rothman’s post for the technical nuances of this, but the basic fact is that the Sony Reader will only allow you to read ebooks that have been formatted and DRMed specifically for the Sony Reader. To be fair, it will let you upload Microsoft Word documents and unencrypted PDFs, but for any more complex, consciously designed electronic book, you’ve got to go through Sony via the Sony Connect store. Sony not only thinks that it can get away with this lock-in strategy but that, taking its cue from the iPod/iTunes dynamo, this is precisely the formula for success. But the iPod analogy is wrong for a number of reasons, biggest among them that books and music are very different things. I’ll address this in another post shortly.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: ebooks are a dead end. Will it be convenient some day to be able to read print books digitally? Certainly. Will the Sony Reader find a niche? Maybe (but Sony Ericsson’s phones look far more dynamic than this feeble device). Is this the future of reading and writing? I don’t think so. Ebooks and their specialized hardware are a red herring in a much bigger and more mysterious plot that is still unfolding.

See also:

– phony reader 2: the ipod fallacy

– phony bookstore

– an open letter to claire israel

Category Archives: publishing

google to scan spanish library books

The Complutense University of Madrid is the latest library to join Google’s digitization project, offering public domain works from its collection of more than 3 million volumes. Most of the books to be scanned will be in Spanish, as well as other European languages (read more in Reuters , or at the Biblioteca Complutense (en espagnol)). I also recently came across news that Google is seeking commercial partnerships with english-language publishers in India.

The Complutense University of Madrid is the latest library to join Google’s digitization project, offering public domain works from its collection of more than 3 million volumes. Most of the books to be scanned will be in Spanish, as well as other European languages (read more in Reuters , or at the Biblioteca Complutense (en espagnol)). I also recently came across news that Google is seeking commercial partnerships with english-language publishers in India.

While celebrating the fact that these books will be online (and presumably downloadable in Google’s shoddy, unsearchable PDF editions), we should consider some of the dynamics underlying the migration of the world’s libraries and publishing houses to the supposedly placeless place we inhabit, the web.

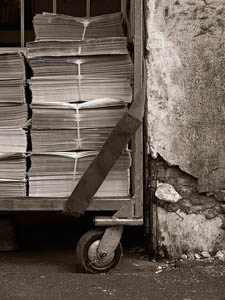

No doubt, Google’s scanners are aquiring an increasingly global reach, but digitization is a double-edged process. Think about the scanner. A photographic technology, it captures images and freezes states. What Google is doing is essentially photographing the world’s libraries and preparing the ultimate slideshow of human knowledge, the sequence and combination of the slides to be determined each time by the queries of each reader.

But perhaps Google’s scanners, in their dutifully accurate way, are in effect cloning existing arrangements of knowledge, preserving cultural trade deficits, and reinforcing the flow of knowledge power — all things we should be questioning at a time when new technologies have the potential to jigger old equations.

With Complutense on board, we see a familiar pyramid taking shape. Spanish takes its place below English in the global language hierarchy. Others will soon follow, completing this facsimile of the existing order.

perelman’s proof / wsj on open peer review

Last week got off to an exciting start when the Wall Street Journal ran a story about “networked books,” the Institute’s central meme and very own coinage. It turns out we were quoted in another WSJ item later that week, this time looking at the science journal Nature, which over the summer has been experimenting with opening up its peer review process to the scientific community (unfortunately, this article, like the networked books piece, is subscriber only).

I like this article because it smartly weaves in the story of Grigory (Grisha) Perelman, which I had meant to write about earlier. Perelman is a Russian topologist who last month shocked the world by turning down the Fields medal, the highest honor in mathematics. He was awarded the prize for unraveling a famous geometry problem that had baffled mathematicians for a century.

I like this article because it smartly weaves in the story of Grigory (Grisha) Perelman, which I had meant to write about earlier. Perelman is a Russian topologist who last month shocked the world by turning down the Fields medal, the highest honor in mathematics. He was awarded the prize for unraveling a famous geometry problem that had baffled mathematicians for a century.

There’s an interesting publishing angle to this, which is that Perelman never submitted his groundbreaking papers to any mathematics journals, but posted them directly to ArXiv.org, an open “pre-print” server hosted by Cornell. This, combined with a few emails notifying key people in the field, guaranteed serious consideration for his proof, and led to its eventual warranting by the mathematics community. The WSJ:

…the experiment highlights the pressure on elite science journals to broaden their discourse. So far, they have stood on the sidelines of certain fields as a growing number of academic databases and organizations have gained popularity.

One Web site, ArXiv.org, maintained by Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y., has become a repository of papers in fields such as physics, mathematics and computer science. In 2002 and 2003, the reclusive Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman circumvented the academic-publishing industry when he chose ArXiv.org to post his groundbreaking work on the Poincaré conjecture, a mathematical problem that has stubbornly remained unsolved for nearly a century. Dr. Perelman won the Fields Medal, for mathematics, last month.

(Warning: obligatory horn toot.)

“Obviously, Nature’s editors have read the writing on the wall [and] grasped that the locus of scientific discourse is shifting from the pages of journals to a broader online conversation,” wrote Ben Vershbow, a blogger and researcher at the Institute for the Future of the Book, a small, Brooklyn, N.Y., , nonprofit, in an online commentary. The institute is part of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center for Communication.

Also worth reading is this article by Sylvia Nasar and David Gruber in The New Yorker, which reveals Perelman as a true believer in the gift economy of ideas:

Perelman, by casually posting a proof on the Internet of one of the most famous problems in mathematics, was not just flouting academic convention but taking a considerable risk. If the proof was flawed, he would be publicly humiliated, and there would be no way to prevent another mathematician from fixing any errors and claiming victory. But Perelman said he was not particularly concerned. “My reasoning was: if I made an error and someone used my work to construct a correct proof I would be pleased,” he said. “I never set out to be the sole solver of the Poincaré.”

Perelman’s rejection of all conventional forms of recognition is difficult to fathom at a time when every particle of information is packaged and owned. He seems almost like a kind of mystic, a monk who abjures worldly attachment and dives headlong into numbers. But according to Nasar and Gruber, both Perelman’s flouting of academic publishing protocols and his refusal of the Fields medal were conscious protests against what he saw as the petty ego politics of his peers. He claims now to have “retired” from mathematics, though presumably he’ll continue to work on his own terms, in between long rambles through the streets of St. Petersburg.

Regardless, Perelman’s case is noteworthy as an example of the kind of critical discussions that scholars can now orchestrate outside the gate. This sort of thing is generally more in evidence in the physical and social sciences, but ought too to be of great interest to scholars in the humanities, who have only just begun to explore the possibilities. Indeed, these are among our chief inspirations for MediaCommons.

Academic presses and journals have long functioned as the gatekeepers of authoritative knowledge, determining which works see the light of day and which ones don’t. But open repositories like ArXiv have utterly changed the calculus, and Perelman’s insurrection only serves to underscore this fact. Given the abundance of material being published directly from author to public, the critical task for the editor now becomes that of determining how works already in the daylight ought to be received. Publishing isn’t an endpoint, it’s the beginning of a process. The networked press is a guide, a filter, and a discussion moderator.

Nature seems to grasp this and is trying with its experiment to reclaim some of the space that has opened up in front of its gates. Though I don’t think they go far enough to effect serious change, their efforts certainly point in the right direction.

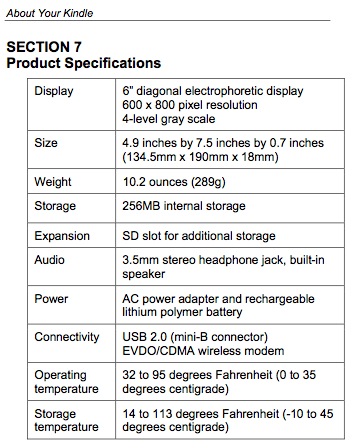

amazon looks to “kindle” appetite for ebooks with new device

Engadget has uncovered details about a soon-to-be-released upcoming/old/bogus(?) Amazon ebook reading device called the “Kindle,” which appears to have an e-ink display, and will presumably compete with the Sony Reader. From the basic specs they’ve posted, it looks like Kindle wins: it’s got more memory, it’s got a keyboard, and it can connect to the network (update: though only through the EV-DO wireless standard, which connects Blackberries and some cellphones; in other words, no basic wifi). This is all assuming that the thing actually exists, which we can’t verify.

Regardless, it seems the history of specialized ebook devices is doomed to repeat itself. Better displays (and e-ink is still a few years away from being really good) and more sophisticated content delivery won’t, in my opinion, make these machines much more successful than their discontinued forebears like the Gemstar or the eBookMan.

Ebooks, at least the kind Sony and Amazon will be selling, dwell in a no man’s land of misbegotten media forms: pale simulations of print that harness few of the possibilities of the digital (apparently, the Sony Reader won’t even have searchable text!). Add highly restrictive DRM and vendor lock-in through the proprietary formats and vendor sites made for these devices and you’ve got something truly depressing.

Publishers need to get out of this rut. The future is in networked text, multimedia and print on demand. Ebooks and their specialized hardware are a red herring.

Teleread also comments.

wall street journal on networked books and GAM3R 7H30RY

The Wall Street Journal has a big story today on networked books (unfortunately, behind a paywall). The article covers three online book experiments, Pulse, The Wealth of Networks, and GAM3R 7H30RY. The coverage is not particularly revelatory. What’s notable is that the press, which over the past decade-plus has devoted so much ink and so many pixels to ebooks, is now beginning to take a look at a more interesting idea. (“The meme is launched!” writes McKenzie.) Here’s the opening section:

Boundless Possibilities

As ‘networked’ books start to appear, consumers, publishers and authors get a glimpse of publishing to come

“Networked” books — those written, edited, published and read online — have been the coming thing since the early days of the Internet. Now a few such books have arrived that, while still taking shape, suggest a clearer view of the possibilities that lie ahead.

In a fairly radical turn, one major publisher has made a networked book available free online at the same time the book is being sold in stores. Other publishers have posted networked titles that invite visitors to read the book and post comments. One author has posted a draft of his book; the final version, he says, will reflect suggestions from his Web readers.

At their core, networked books invite readers online to comment on a written text, and more readers to comment on those comments. Wikipedia, the open-source encyclopedia, is the ultimate networked book. Along the way, some who participate may decide to offer up chapters translated into other languages, while still others launch Web sites where they foster discussion groups centered on essays inspired by the original text.

In that sense, networked books are part of the community-building phenomenon occurring all over the Web. And they reflect a critical issue being debated among publishers and authors alike: Does the widespread distribution of essentially free content help or hinder sales?

If the Journal would make this article available, we might be able to debate the question more freely.

“a duopoly of Reuters-AP”: illusions of diversity in online news

Newswatch reports a powerful new study by the University of Ulster Centre for Media Research that confirms what many of us have long suspected about online news sources:

Through an examination of the content of major web news providers, our study confirms what many web surfers will already know – that when looking for reporting of international affairs online, we see the same few stories over and over again. We are being offered an illusion of information diversity and an apparently endless range of perspectives which in fact what is actually being offered is very limited information.

The appearance of diversity can be a powerful thing. Back in March, 2004, the McClatchy Washington Bureau (then Knight Ridder) put out a devastating piece revealing how the Iraqi National Congress (Ahmad Chalabi’s group) had fed dubious intelligence on Iraq’s WMDs not only to the Bush administration (as we all know), but to dozens of news agencies. The effect was a swarm of seemingly independent yet mutually corroborating reportage, edging American public opinion toward war.

A June 26, 2002, letter from the Iraqi National Congress to the Senate Appropriations Committee listed 108 articles based on information provided by the INC’s Information Collection Program, a U.S.-funded effort to collect intelligence in Iraq.

The assertions in the articles reinforced President Bush’s claims that Saddam Hussein should be ousted because he was in league with Osama bin Laden, was developing nuclear weapons and was hiding biological and chemical weapons.

Feeding the information to the news media, as well as to selected administration officials and members of Congress, helped foster an impression that there were multiple sources of intelligence on Iraq’s illicit weapons programs and links to bin Laden.

In fact, many of the allegations came from the same half-dozen defectors, weren’t confirmed by other intelligence and were hotly disputed by intelligence professionals at the CIA, the Defense Department and the State Department.

Nevertheless, U.S. officials and others who supported a pre-emptive invasion quoted the allegations in statements and interviews without running afoul of restrictions on classified information or doubts about the defectors’ reliability.

Other Iraqi groups made similar allegations about Iraq’s links to terrorism and hidden weapons that also found their way into official administration statements and into news reports, including several by Knight Ridder.

The repackaging of information goes into overdrive with the internet, and everyone, from the lone blogger to the mega news conglomerate, plays a part. Moreover, it’s in the interest of the aggregators and portals like Google and MSN to emphasize cosmetic or brand differences, so as to bolster their claims as indispensible filters for a tidal wave of news. So whether it’s Bush-Cheney-Chalabi’s WMDs or Google News’s “4,500 news sources updated continuously,” we need to maintain a skeptical eye.

***Related: myths of diversity in book publishing and large-scale digitization efforts.

on business models in web publishing

Here at the Institute, we’re generally more interested in thinking up new forms of publishing than in figuring out how to monetize them. But one naturally perks up at news of big money being made from stuff given away for free. Doc Searls points to a few items of such news.

First, that latest iteration of the American dream: blogging for big bucks, or, the self-made media mogul. Yes, a few have managed to do it, though I don’t think they should be taken as anything more than the exceptions that prove the rule that most blogs are smaller scale efforts in an ecology of niches, where success is non-monetary and more of the “nanofame” variety that iMomus, David Weinberger and others have talked about (where everyone is famous to fifteen people). But there is that dazzling handful of popular bloggers that rival the mass media outlets, and they’re raking in tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars in ad revenues.

Some sites mentioned in the article:

— TechCrunch: “$60,000 in ad revenue every month” (not surprising — its right column devoted to sponsors is one of the widest I’ve seen)

— Boing Boing: “on track to gross an estimated $1 million in ad revenue this year”

— paidContent.org: over a million a year

— Fark.com: “on pace to become a multimillion-dollar property.

Then, somewhat surprisingly, is The New York Times. Handily avoiding the debacle predicted a year ago by snarky bloggers like myself when the paper decided to relocate its op-ed columnists and other distinctive content behind a pay wall, the Times has pulled in $9 million from nearly 200,000 web-exclusive Times Select subscribers, while revenues from the Times-owned About.com continue to skyrocket. There’s a feeling at the company that they’ve struck a winning formula (for now) and will see how long they can ride it:

When I ask if TimesSelect has been successful enough to suggest that more material be placed behind the wall, Nisenholtz [senior vice president for digital operations] replies, “The strategy isn’t to move more content from the free site to the pay site; we need inventory to sell to advertisers. The strategy is to create a more robust TimesSelect” by using revenue from the service to pay for more unique content. “We think we have the right formula going,” he says. “We don’t want to screw it up.”

***Subsequent thought: I’m not so sure. Initial indicators may be good, but I still think that the pay wall is a ticket to irrelevance for the Times’ columnists. Their readership is large and (for now) devoted enough to maintain the modestly profitable fortress model, but I think we’ll see it wither over time.***

Also, in the Times, there’s this piece about ad-supported wiki hosting sites like Wikia, Wetpaint, PBwiki or the swiftly expanding WikiHow, a Wikipedia-inspired how-to manual written and edited by volunteers. Whether or not the for-profit model is ultimately compatible with the wiki work ethic remains to be seen. If it’s just discrete ads in the margins that support the enterprise, then contributors can still feel to a significant extent that these are communal projects. But encroach further and people might begin to think twice about devoting their time and energy.

***Subsequent thought 2: Jesse made an observation that makes me wonder again whether the Times Company’s present success (in its present framework) may turn out to be short-lived. These wiki hosting networks are essentially outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing” as the latest jargon goes, the work of the hired About.com guides. Time will tell which is ultimately the more sustainable model, and which one will produce the better resource. Given what I’ve seen on About.com, I’d place my bets on the wikis. The problem? You, or your community, never completely own your site, so you’re locked into amateur status. With Wikipedia, that’s the point. But can a legacy media company co-opt so many freelancers without pay? These are drastically different models. We’re probably not dealing with an either/or here.***

We’ve frequently been asked about the commercial potential of our projects — how, for instance, something like GAM3R 7H30RY might be made to make money. The answer is we don’t quite know, though it should be said that all of our publishing experiments have led to unexpected, if modest, benefits — bordering on the financial — for their authors. These range from Alex selling some of his paintings to interested commenters at IT IN place, to Mitch gradually building up a devoted readership for his next book at Without Gods while still toiling away at the first chapter, to McKenzie securing a publishing deal with Harvard within days of the Chronicle of Higher Ed. piece profiling GAM3R 7H30RY (GAM3R 7H30RY version 1.2 will be out this spring, in print).

Build up the networks, keep them open and toll-free, and unforseen opportunities may arise. It’s long worked this way in print culture too. Most authors aren’t making a living off the sale of their books. Writing the book is more often an entree into a larger conversation — from the ivory tower to the talk show circuit, and all points in between. With the web, however, we’re beginning to see the funnel reversed: having the conversation leads to writing the book. At least in some cases. At this point it’s hard to trace what feeds into what. So many overlapping conversations. So many overlapping economies.

dexter sinister and just in time publishing

Deep in Manhattan where the lines between Chinatown and the Lower East Side blur, the basement of a non-descript building houses a graphic design firm / publishing house / bookstore. The entrance is easy to miss, with a small spray-painted trumpet, taken from Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying Lot of 49, marking a handrail. However on Saturdays, hinged metal basement doors are left open, signaling that “Dexter Sinister: Just-In-Time Workshop & Occasional Bookstore” is open.

Deep in Manhattan where the lines between Chinatown and the Lower East Side blur, the basement of a non-descript building houses a graphic design firm / publishing house / bookstore. The entrance is easy to miss, with a small spray-painted trumpet, taken from Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying Lot of 49, marking a handrail. However on Saturdays, hinged metal basement doors are left open, signaling that “Dexter Sinister: Just-In-Time Workshop & Occasional Bookstore” is open.

Dexter Sinister is the moniker that designers David Reinfurt and Stuart Bailey adopted last spring to describe the various forms their work takes. I’ve known David for a number of years, but haven’t talked to him in a while. A few Saturdays ago I stopped by Dexter Sinister catch up with him to see “Just in Time Workshop” in action.

Before stopping by, I checked out their website, and saw that they are playing with and pushing against traditions of publishing in some interesting ways.

From their site:

“In the basement at 38 Ludlow Street we will set up a fully-functioning Just-In-Time workshop, against waste and challenging the current state of over-production driven by the conflicting combination of print economies-of-scale (it only makes financial sense to produce large quantities) and the contained audiences of art world marketing (no profit is really expected, and not many copies really need to be made.) These divergent criteria are too often manifested in endless boxes of unsaleable stock taking up space which needs to be further financed by galleries, distributors, bookstores, etc. This over-production then triggers a need to overcompensate with the next, and so on and so on. Instead, all our various production and distribution activities will be collapsed into the basement, which will double as a bookstore, as well as a venue for intermittent film screenings, performance and other events.”

The Occasional bookstore sells copies of works of their own, their colleagues, and work put out from other small presses. The inventory consists of a handful of these titles at a time, which can fit on one shelf in the corner, in my estimation without irony. In fact, the bookstore’s size precisely fits the overall Dexter Sinister ethos.

Further back, I saw a mimeograph, an Apple Image Write printer and an IBM electric typewriter that were all lined up in a row. David noted that he does not overly romanticize the mechanical age of print technology with these similarly monochromatic tan-brown machines. This is, his interest is not in retro for retro’s own sake. Rather, when printer technology was mostly mechanical (rather than computerized,) designers and publishers could tinker, fix and modify their equipment. Car enthusiasts have noted a similar loss, as automobiles have become increasingly computerized as well.

Dexter Sinister produce their books in small runs that are meant to sell out. Further, their publications tend to be highly selective, limited, and personal. However, they aren’t gatekeepers. Instead, the overall impression is that they are interested in supportive projects that matter to them. For instance, Dexter Sinister now produces “dot dot dot,” the design periodical that Stuart co-edited and designed while living in the Netherlands. When the print runs do sell out, they can issue re-prints in any number of printing options depending upon the circumstance, if they want to, or not.

Some of their publications are printed on their mimeograph. While being well designed, the printing is fast and inexpensive, but avoids feeling overly cheap. Although, the final result reminds me of the pirated textbooks I encountered in China in the mid 90s. Inexpensive doesn’t necessarily mean boring and poor quality. Rather, it provides another design constraint under which to find new solutions. They’re also experimenting with lulul.com and have done born-digital projects as well.

Some of their publications are printed on their mimeograph. While being well designed, the printing is fast and inexpensive, but avoids feeling overly cheap. Although, the final result reminds me of the pirated textbooks I encountered in China in the mid 90s. Inexpensive doesn’t necessarily mean boring and poor quality. Rather, it provides another design constraint under which to find new solutions. They’re also experimenting with lulul.com and have done born-digital projects as well.

What’s really interesting to me is that DS and the institute share many ideas in common. However the execution of these ideas and solutions are entirely different. Although, the institute’s foci are often pointed at the digital, we certainly support the future of print (despite the fact that we get asked to comment or qualify the position of “death of print” quite often.) Distribution of digital media via the network is one vector. Small run, niche, highly curated, print publishing is another. In both cases, we have run into the failures of the current economic models of many traditional kinds of publishing. I’m reminded of the analogy of water, flowing down a mountain, seeking a path of minimal resistance. Similarly, information “wants” to intrinsically find its expression by the easiest pathways.

Later in a follow-up email exchange, we were talking about these various new modes of publishing. David noted that, “it feels like some particular in-between moment, just in general, with an overall apocalyptic vibe. It’s definitely the end of something and I suppose the beginning of something else.” Exactly.

google offers public domain downloads

Google announced today that it has made free downloadable PDFs available for many of the public domain books in its database. This is a good thing, but there are several problems with how they’ve done it. The main thing is that these PDFs aren’t actually text, they’re simply strings of images from the scanned library books. As a result, you can’t select and copy text, nor can you search the document, unless, of course, you do it online in Google. So while public access to these books is a big win, Google still has us locked into the system if we want to take advantage of these books as digital texts.

A small note about the public domain. Editions are key. A large number of books scanned so far by Google have contents in the public domain, but are in editions published after the cut-off (I think we’re talking 1923 for most books). Take this 2003 Signet Classic edition of the Darwin’s The Origin of Species. Clearly, a public domain text, but the book is in “limited preview” mode on Google because the edition contains an introduction written in 1958. Copyright experts out there: is it just this that makes the book off limits? Or is the whole edition somehow copyrighted?

Other responses from Teleread and Planet PDF, which has some detailed suggestions on how Google could improve this service.

book trailers, but no network

We often conceive of the network as a way to share culture without going through the traditional corporate media entities. The topology of the network is created out of the endpoints; that is where the value lies. This story in the NY Times prompted me to wonder: how long will it take media companies to see the value of the network?

The article describes a new marketing tool that publishers are putting into their marketing arsenal: the trailer. As in a movie trailer, or sometimes an informercial, or a DVD commentary track.

“The video formats vary as widely as the books being pitched. For well-known authors, the videos can be as wordy as they are visual. Bantam Dell, a unit of Random House, recently ran a series in which Dean Koontz told funny stories about the writing and editing process. And Scholastic has a video in the works for “Mommy?,” a pop-up book illustrated by Maurice Sendak that is set to reach stores in October. The video will feature Mr. Sendak against a background of the book’s pop-ups, discussing how he came up with his ideas for the book.”

Who can fault them for taking advantage of the Internet’s distribution capability? It’s cheap, and it reaches a vast audience, many of whom would never pick up the Book Review. In this day and age, it is one of the most cost effective methods of marketing to a wide audience. By changing the format of the ad from a straight marketing message to a more interesting video experience, the media companies hope to excite more attention for their new releases. “You won’t get young people to buy books by boring them to death with conventional ads,” said Jerome Kramer, editor in chief of The Book Standard.”

But I can’t help but notice that they are only working within the broadcast paradigm, where advertising, not interactivity, is still king. All of these forms (trailer, music video, infomercial) were designed for use with television; their appearance in the context of the Internet further reinforces the big media view of the ‘net as a one-way broadcast medium. A book is a naturally more interactive experience than watching a movie. Unconventional ads may bring more people to a product, but this approach ignores one of the primary values of reading. What if they took advantage of the network’s unique virtues? I don’t have the answers for this, but only an inkling that publishing companies would identify successes sooner and mitigate flops earlier, that the feedback from the public would benefit the bottom line, and that readers will be more engaged with the publishing industry. But the first step is recognizing that the network is more than a less expensive form of television.