On my way to that rather long discussion of ARGs the other day, I fielded something Pat Kane said to me a while back about the growing importance of live gigs to the income of musicians.

So I was tickled when Paul Miller pointed me to a piece Chris Anderson blogged yesterday about the same thing. Increasingly, musicians are giving their music away for free in order to drive gig attendance – and it’s driving music reproduction companies crazy. And yet, what can they do? “The one thing that you can’t digitize and distribute with full fidelity is a live show”.

A minor synchronicity; but then I stop by here and find Gary Frost and bowerbird vigorously debating the likeliness of the digitisation of everything, and of the death of ‘the original’ as even a concept, in the context of Ben’s piece about the National Archives sellout. And then I remember that, the day before, someone sent me a spoof web page telling me to get a First Life. And I start to wonder if there’s some kind of post-digital backlash taking shape.

OK, Anderson is talking about music; it’s hard to speculate about how the manifest ‘authentic’ appeal of a time-bound, ephemeral ‘gig’ experience translates literally to the field of physical books without falling back into diaphanous stuff about tactility and marginalia and so on. But, in the light of people’s manifest willingness to pay ridiculous sums to see the ‘real’ Madonna in real time and space, is it really feasible to talk, as bowerbird does, about the coming digitisation of everything?

As far as I can see, as more digitisation progresses, authenticity is becoming big business. I think it’s worth exploring the possibilities of a split between ‘book’ as pure content, and book as ‘authentic’ object. In particular, I think it’s worth exploring the possible economics of this: the difference in approach, genesis, theory, self-justification, style and paycheque of content created for digital reproduction, and text created for tangible books. And finally, I think whoever manages to sus both has probably got it made.

Category Archives: publishing

unbound – google publishing conference at NYPL

Interesting bit of media industry theater here. I’m here in the New York Public Library, one of the city’s great temples to the book, where Google has assembled representatives of the book business to undergo a kind of group massage. A pep talk for a timorous publishing industry that has only barely dipped its toes in the digital marketplace and can’t decide whether to regard Google as savior or executioner. The speaker roster is a mix of leading academic and trade publishers and diplomatic envoys from the techno-elite. Chris Anderson, Cory Doctorow, Seth Godin, Tim O’Reilly have all spoken. The 800lb. elephant in the room is of course the lawsuits brought against Google (still in the discovery phase) by the Association of American Publishers and the Authors’ Guild for their library digitization program. Doctorow and O’Reilly broached it briefly and you could feel the pulse in the room quicken. Doctorow: “We’re a cabal come over from the west coast to tell you you’re all wrong!” A ripple of laughter, acid-laced. A little while ago Michael Holdsworth of Cambridge University Press pointed to statistics that suggest that Book Search is driving up their sales… Some grumble that the publishers’ panel was a little too hand-picked.

Google’s tactic here seems simultaneously to be to reassure the publishers while instilling an undercurrent of fear. Reassure them that releasing more of their books in a greater variety of forms will lead to more sales (true) — and frightening them that the technological train is speeding off without them (also true, though I say that without the ecstatic determinism of the Google folks. Jim Gerber, Google’s main liason to the publishing world, opened the conference with a love song to Moore’s Law and the gigapixel camera, explaining that we’re within a couple decades’ reach of having a handheld device that can store all the content ever produced in human history — as if this fact alone should drive the future of publishing). The event feels more like a workshop in web marketing than a serious discussion about the future of publishing. It’s hard to swallow all the marketing speak: “maximizing digital content capabilities,” “consolidation by market niche”; a lot of talk of “users” and “consumers,” but not a whole lot about readers. Publishers certainly have a lot of catching up to do in the area of online commerce, but barely anyone here is engaging with the bigger questions of what it means to be a publisher in the network era. O’Reilly sums up the publisher’s role as “spreading the knowledge of innovators.” This is more interesting and O’Reilly is undoubtedly doing more than almost any commercial publisher to rethink the reading experience. But most of the discussion here is about a culture industry that seems more concerned with salvaging the industry part of itself than with honestly rethinking the cultural part. The last speaker just wrapped up and it’s cocktail time. More thoughts tomorrow.

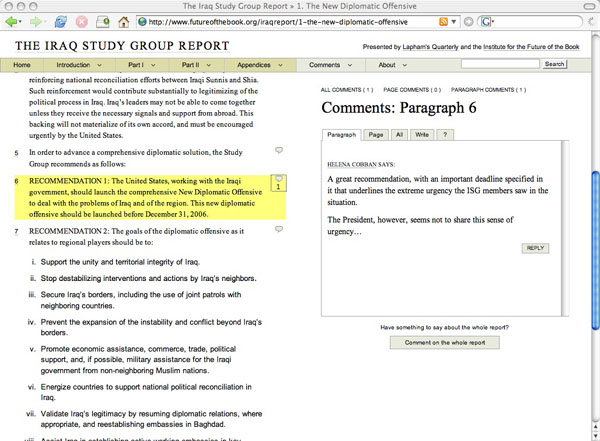

bush’s iraq speech: a critical edition

Last month we published an online edition of the Iraq Study Group Report in a new format we’re developing (in-house name is “Comment Press”) that allows readers to enter into conversation with a text and with one another. This was a first step in a creative partnership with Lewis Lapham and Lapham’s Quarterly, a new journal that will look at contemporary issues through the lens of history. Launching only a few days before Christmas, the timing was certainly against us. Only a handful of commenters showed up in those first few days, slowing down almost to a halt as the holiday hibernation period set in. Since New Year’s, however, the site has been picking up momentum and has now amassed a sizable batch of commentary on the Report from a diverse group of respondents including Howard Zinn, Frances FitzGerald and Gary Hart.

While that discussion continues to develop in the Report’s margins, we are following it up with a companion text: the transcript and video of President Bush’s address to the nation last night where he outlined his new strategy for Iraq, presented in a similarly Talmudic fashion with commentary accreting around the central text. To these two documents invited readers and other interested members of the public can continue to append their comments, criticisms and clarifications, “at liberty to find,” in Lapham’s words, “‘the way forward’ in or out of Iraq, back to the future or across the Potomac and into the trees.”

An added feature this time around is that we’re opening the door to general commenters, although with a fairly high barrier to entry. This is an experiment with a more rigorously moderated kind of web discussion and a chance for Lapham and his staff to begin to explore what it means to be editors in the network environment. Anyone is welcome to apply for entry into the discussion by providing a little background on themselves and a sample first comment. If approved by the Lapham’s Quarterly editors (this will all happen within the same day), they will be given a login, at which point they can fire at will on both the speech and the report.

Together these two publications comprise Operation Iraqi Quagmire, a journalistic experiment and a gesture toward a new way of handling public documents in a networked democracy.

***Note: we strongly recommend viewing this on Firefox***

the end of media industries

Imagine a world without publishers, broadcasters or record labels. Imagine the complex infrastructure, large distribution networks, massive advertising campaigns, and multi-million signing contracts provided by the media incumbents all gone from our society. What would our culture look like? Will the music stop? Will pens dry up?

I would hope not, but I recently read Siva Vaidhyanathan’s book, The Anarchist in the Library, and I encountered a curious quote from Time Warner CEO, Richard Parsons:

This is a very profound moment historically. This isn’t just about a bunch of kids stealing music. It’s an assault on everything that constitutes cultural expression of our society. If we fail to protect and preserve out intellectual property system, the culture will atrophy. And the corporations wont be the only ones hurt. Artists will have no incentive to create. Worst-case scenario: the country will end up in a sort of Cultural Dark Age.

The idea that “artists will have no incentive to create” without corporations’ monetary promise goes against everything we know about the creative mind. Through out human history, self-expression has existed under the extreme conditions, for little or no gain; if anything, self-expression has flourished under the most unrewarding conditions. Now we that the Internet provides a medium to share information, people will create.

A fundamental misunderstanding in the relationship between media industry and the artist has produced an environment that has led the industry to believe that they are the reason for creative output, not just a beneficiary. However, the Internet is bringing the power of production and distribution to the user. And if production and distribution — which are where historically media companies made their money — can be handled by users, then what will be left for the media companies? With the surge in content, will media companies need to become filters and editors? If not, then what is there?

The current media model depends on controlling the flow of information, and as information becomes harder to control their power will diminish. On the internet we see strong communities building around very specific niches. As these communities get stronger, they will become harder to compete with. I believe that these niches will develop into the next generation media companies. These will be the companies that the large media companies will need to compete with.

The challenges that the current media companies face remind me of what happened to AT&T in the 1990s. After being broken up into “baby-bells”, AT&T was left providing only long distance. It was just a matter of time before the “baby-bells” began eating away at AT&T’s business from below, and there was little AT&T could do about it.

I think Richard Parsons’ quote shows a misunderstanding not only in the reason why people share information, but also in the direction of new technologies. For that reason I do not have much hope for the current media companies to adjust. Their only hope is to change and change represents their demise.

retreat to his study / thoughts for ’07

2006 was a big year for the Institute. We emerged as a sort of publishing lab, a place for authors and readers to rethink books in the digital age — both theoretically (in the wide-ranging dicussions on this blog) and practically (in hands-on experimentation). The project that got things rolling on the practical end — and which is now wrapping up its current phase and down-shifting tempo — was undoubtedly Mitch Stephens’ book blog Without Gods. Like many of our experiments, this one emerged not by some grand design but through an offhand suggestion, when we thought we were headed somewhere else.

Two Novembers ago Bob and I were meeting Mitch for lunch at a cafe near NYU to chat about blogging and its impact on the news media (remember that Mitch, though lately preoccupied with the history of atheism, is a professor in the journalism program at NYU). We were preparing to host a meeting at USC of leading academic bloggers to discuss how scholars were beginning to use blogs to enliven discourse in their fields, and how certain ones (like Juan Cole and PZ Myers) were reaching a general readership, bringing their knowledge to bear on media coverage of subjects like Iraq or the intelligent design movement.

At one point during the lunch it came up that Mitch was in the early stages of researching a new book on nonbelievers and the idea was tossed out — I suppose in the spirit of the discussion — that he start a blog to see how the writing process might be opened up in real time, engaging readers in dialog. Mitch seemed intrigued (guardedly) and said he’d think it over.

A few weeks later, back from a fascinating time in LA, I was pleasantly surprised to receive an email from Mitch saying that he’d been considering the blog idea and wanted to give it a shot. We’d returned from the USC meeting pretty charged up by the discussion we had there and convinced that blogging represented at least the primitive beginnings of a major reorganization of scholarly and public discourse. But we were at a loss as to what our small outfit could do to help. Mitch’s email, if not the answer to all our questions, seemed like a great way to get our hands dirty making a tangible product and would perhaps help us to figure out our next steps. We had a few brainstorm meetings, pulled together a basic design, and Without Gods was born.

A year on, I think it’s safe to say that it’s been a success — actually a turning point for us in balancing the proportions in our work of theoretical pondering to practical experimentation. It’s somewhat ironic that the most substantial thing to come out of the academic blogging inquiry was slightly to the side of the initial question, and conceived before the meeting. But that’s often how things occur. Questions lead to other questions. Without Gods led to Gamer Theory, Gamer Theory led to Holy of Holies, which in turn led to the Iraq Study Group Report. Which I suppose all in some way stems from the academic blogging inquiry and the many tributaries it opened up. MediaCommons is steeped in a belief in the importance of vibrant and visible conversation among scholars in forms ranging from the blog to the networked book — values laid out in the original USC gathering, and developed through our work on Without Gods and beyond.

Now, as hinted before, Mitch has decided it’s time to retreat to his study in order to bring the book to fruition — offline. As he forges ahead, however, he’ll carry with him the echoes — and the archive — of the past year’s discussions.

After a year of mostly daily blogging on this site, I am cutting back.

As most of you know, I am writing a book on the history of disbelief for Carroll and Graf. The blog — produced while working on the book — was an experiment conceived by the Institute for the Future of the Book. It has been a success. I have been benefiting from informed and insightful comments by readers of the blog as I’ve tested some ideas from this book and explored some of their connections to contemporary debates.

I may continue to post sporatically here, but now it seems time to retreat to my study to digest what I’ve learned, polish my thoughts and compose the rest of the narrative. The trick will be accomplishing that without losing touch with those – commenters or just silent readers – who are interested in this project….do try to check back here once in a while. There will be some updates and, perhaps, some new experiments.

New experiments such as “Holy of Holies,” a paper that Mitch delivered last month before an NYU working group on “Secularism, Religious Authority, and the Mediation of Knowledge” (it’s still humming with over a hundred comments). Although blog posting will be sporadic, futureofthebook.org/mitchellstephens will remain the internet hub for Mitch’s book, sections of which may appear in draft state in a format similar to the NYU paper (depending on where Mitch, and his publisher, are at). If you’d like to be notified directly of such developments, there’s a form on the site where you can enter your email address.

Thanks, Mitch, and best of luck. We couldn’t have asked for a better partner in exploring this transitional territory. I hope 2007 proves to be as interesting and as healthy a mix of thinking and doing, for you and for us.

live, on the web, it’s the iraq study group report!

Since leaving Harper’s last spring, Lewis Lapham has been developing plans for a new journal, Lapham’s Quarterly, which will look at important contemporary subjects (one per issue) through the lens of history. Not long ago, Lewis approached the Institute about helping him and his colleagues to develop a web component of the Quarterly, which he imagined as a kind of unorthodox news site where history and source documents would serve as a decoder ring for current events — a trading post of ideas, facts, and historical parallels where readers would play a significant role in piecing together the big picture. To begin probing some of the possibilities for this collaboration, we came up with an exciting and timely experiment: we’ve taken the granular commenting format that we hacked together just a few weeks ago for Mitch Stephens’ paper and plugged in the Iraq Study Group Report. The Lapham crew, for their part, have taken their first editorial plunge into the web, using their broad print network to assemble an astonishing roster of intellectual heavyweights to collectively annotate the text, paragraph by paragraph, live on the site. Here’s more from Lewis:

As expected and in line with standard government practice, the report issued by the Iraq Study Group on December 6th comes to us written in a language that guards against the crime of meaning–a document meant to be admired as a praise-worthy gesture rather than understood as a clear statement of purpose or an intelligible rendition of the facts. How then to read the message in the bottle or the handwriting on the wall?

Lapham’s Quarterly and the Institute for the Future of the Book answers the question with a new form of discussion and critique– an annotated edition of the ISG Report on a website programmed to that specific purpose, evolving over the course of the next three weeks into a collaborative illumination of an otherwise black hole. What you have before you is the humble beginnings of that effort–the first few marginal notes and commentaries furnished by what will eventually be a large number of informed sources both foreign and domestic (historians, military officers, politicians, intelligence operatives, diplomats, some journalists), invited to amend, correct, augment or contradict any point in the text seemingly in need of further clarification or forthright translation into plain English.

As the discussion adds to the number of its participants so also it will extend the reach of its memory and enlarge its spheres of reference. What we hope will take shape on short notice and in real time is the publication of a report that should prove to be a good deal more instructive than the one distributed to the members of Congress and the major news media.

Being at the very beginning of the experiment, what you’ll see on the site today is more or less a blank slate. Our hope is that in the days and weeks ahead, a lively conversation will begin to bubble up in the pages of the report — a kind of collaborative marginalia on a grand scale — mounting toward Bush’s big Iraq strategy speech next month. Around that time, the Lapham’s editors will open up commenting to the public. Until then, here are just some of the people we expect to participate: Anthony Arnove, Helena Cobban, Joshua Cohen, Jean Daniel, Raghida Dergham, Joan Didion, Mark Danner, Barbara Ehrenrich, Daniel Ellsberg, Tom Engelhardt, Stanley Fish, Robert Fisk, Eric Foner, Christopher Hitchens, Rashid Khalidi, Chalmers Johnson, Donald Kagan, Kanan Makiya, William Polk, Walter Russel Mead, Karl Meyer, Ralph Nader, Gianni Riotta, M.J. Rosenberg, Gary Sick, Matthew Stevenson, Frances Stonor, Lally Weymouth, and Wayne White.

Not too shabby.

The form is still very much in the R&D phase, but we’ve made significant improvements since the last round. Add this to your holiday reading stack and watch how it develops.

(We strongly recommend viewing the site in Firefox.)

report on scholarly cyberinfrastructure

The American Council of Learned Societies has just issued a report, “Our Cultural Commonwealth,” assessing the current state of scholarly cyberinfrastructure in the humanities and social sciences and making a series of recommendations on how it can be strengthened, enlarged and maintained in the future.

The definition of cyberinfastructure they’re working with:

“the layer of information, expertise, standards, policies, tools, and services that are shared broadly across communities of inquiry but developed for specific scholarly purposes: cyberinfrastructure is something more specific than the network itself, but it is something more general than a tool or a resource developed for a particular project, a range of projects, or, even more broadly, for a particular discipline.”

I’ve only had time to skim through it so far, but it all seems pretty solid.

John Holbo pointed me to the link in some musings on scholarly publishing in Crooked Timber, where he also mentions our Holy of Holies networked paper prototype as just one possible form that could come into play in a truly modern cyberinfrastructure. We’ve been getting some nice notices from others active in this area such as Cathy Davidson at HASTAC. There’s obviously a hunger for this stuff.

how would you design the iraq study group report for the web?

The “Iraq Study Group Report” paperback could have been wrapped in a brown paper bag, its title scrawled in Magic Marker. It would still sell. This is a book, unlike trillions of others on the market, whose substance and national import sell it, not its cover…Disproving the adage, this genre of book can indeed be judged by its cover. From the reports on the Warren Commission to Watergate, Iran-contra and now the Iraq war, such books are anomalies for a publishing industry that churns out covers intended to seduce readers, to reach out and grab them, and propel them to the cash register.

How would you design an unauthorized web edition of the ISG Report? Would you keep to the sober, no-nonsense aesthetic of the iconic print editions of past government documents like the 9/11 Commission Report or the Warren Commission Report? Or would you shake things up? A far more interesting question: what functionality would you add? What kind of discussion capabilities would you build into it? Who would you most like to see annotate or publicly comment on the document?

The electronic edition that has been making the rounds is an austere PDF made available by the United States Institute of Peace. A far more useful resource for close reading of the text was put out by Vivismo as a demonstration of its new Velocity Search Engine. They crawled the PDF and broke it into individual paragraphs, adding powerful clustered search tools.

The US Government Printing Office has a slew of public documents available on its website, mostly as PDFs or bare-bones HTML pages. How should texts of “national import” be reconceived for the network?

do editors dream of electrifying networks?

Lindsay Waters, executive editor for the humanities at Harvard University Press, mentions the Gamer Theory “experiment” in an interview at The Book Depository:

BD: What are the principal challenges/opportunities you see at the moment in the business of publishing books?

LW: The principal challenge is that the book market is changing drastically. The whole plate techtonics is in motion. One chief challenge is not to get unnerved, not to believe Chicken Little as he runs up and down Main Street screaming “the sky is falling.” Books are not going to disappear. We have to experiment with the book which is what we are doing when, for example, we publish McKenzie Wark’s Hacker Manifesto and his forthcoming Gamer Theory.

Gamer Theory is a book that is already available on the web in electronic form, but we believe there is enough of a market for the print version of the book to justify our publishing the book in hardcover. This is an experiment.

One hopes the experimentation doesn’t end here. Last week, we had some very interesting discussions here on the evolution of authorship, which, while never going explicitly into the realm of editing, are nonetheless highly relevant in that regard. In one particularly excellent a comment, Sol Gaitan laid out the challenge for a new generation of writers, which I think could go just as well for a nascent class of digital editors:

…the immediacy that the Internet provides facilitates collaboration in a way no meeting of minds in a cafe or railroad apartment ever had. This facilitates a communality that approaches that of the oral tradition, now we have a system that allows for true universality. To make this work requires action, organization, clarity of purpose, and yes, a new rhetoric. New ways of collaboration entail a novel approach.

Someone is almost certainly going to be needed to moderate the discussions that come out of these complex processes, especially considering that the discussions themselves may consitute the bulk of the work. This task will in part be taken up by the author, and by the communities themselves (that’s largely how things have developed so far) but when you begin to imagine numerous clusters of projects overlapping and cross-pollinating, it seems obvious that a special kind of talent will be required to see the big picture. Call it curating the collective — redacting the remix. Organizing networks will become its own kind of art.

Later on in the interview, Waters says: “I am most proud of the way so many of my books constellate. I see these links in my books in literature, philosophy, and also in economics…” Editors have always been in the business of networks — the business of interlinking. More are now waking up to the idea that web and print can work productively, and even profitably, together. But this is at best a transitional stage. Unless editors reckon with the fact that the internet presents not just a new way of distributing texts but a new way of making them, plate techtonics will continue to destabilize the publishing industry until it breaks apart and slides into the sea.

do bloggers dream of electrifying text?

I left Oxford four years ago, as a fresh-faced English graduate, clutching my First and ready to take the world by storm. The first things that happened were

1) I got fired several times in quick succession for being more interested in writing than business

2) I wrote the usual abortive Bildungsroman-type first attempt at a novel, and then realised it was rubbish

3) I wrote another one, close but no cigar

4) I stopped trying to ‘be a writer’, and suddenly discovered myself writing more than ever.

But I’ve stopped wanting to write books. Perhaps, in the light of Ben’s post on Vidal and the role of authors, I should explain why.

Part of the problem is that between events 1) and 4) above, I discovered the Internet. I found myself co-editing a collaboratively-written email newsletter that covered the kinds of grass-roots creative and political stuff I wanted to be involved in. I thrashed out swathes of cultural theory in a wiki. I blogged for a while in sonnet form. As a side-effect, I nearly started an art collective in France. I found exciting projects and got involved in them. I’m now working on a startup based on (real and virtual) discussions I had with people I met this way. These days, my writing goes into emails, proposals, and the blogosphere. If I get the yen to write fiction, I do so, in collaboration with friends, on the vintage typewriter in my sitting room.

You could say that I just don’t have time to write a whole book. But it’s not just about time. In the process of learning all these new reasons for writing, I stopped aspiring to be an Author.

To backtrack a bit. In the process of frogmarching me through most of the English literary canon from 10AD to the twentieth century, my tutors put a lot of effort into making me consider the relationship between literary theories and their sociopolitical contexts. So I learned how, in Elizabethan England, the writer’s job was to improve politics by providing aspirational images of political leaders. These days, it looks like sycophancy, but back then they (at least say they) believed that the addressee would be moved by poems describing their ideal self to try and become that self, and that this was a valid contribution to the social good.

Fast-forward a hundred or so years. Print technology is taking off in a big way, and in post-Civil War England, aristocratic patronage is declining, and rhetoric is deeply suspect. So writers such as Pope retroengineered the writings of Shakespeare (and, by implication, their own) to represent an ‘eternal’ canon of ‘great’ writing supposedly immune to the ravages of time. This enabled them to distinguish ‘great’ writing from ‘hack’ writing independent of the political situation, thus conveniently providing themselves with a job description (‘great writer’) that didn’t depend on sucking up to a rich patron under the guise of laus et vituperatio but instead sold directly to the public through the burgeoning print industry.

That, then (if you’ll forgive the egregious over-simplification), is the model of what and who an ‘author’ is. We’ve been stuck with it pretty much since then. It depends on the immutable, printed page, requires authors to turn themselves into a brand in order to make a living by marketing their branded ‘great’ prose to the great unwashed for – of course – the improvement not of the authors but of said unwashed, and supports a whole industry in the production and sale of books.

And then came the Internet. All of a sudden, writing is infinitely reproducible. Anyone who wants to write can self-publish. There are tools for real-time collaborative writing. And yet the popular conception of who or what an Author is still very much alive, in the popular mind at least. The publishing industry, meanwhile, has responded to the threat posed by the Net by consolidating, automating, and producing only books guaranteed to sell millions.

So I found myself, a few years out of university, considering the highly-industrialised modern print industry, in the context of the literary theories and social contexts that have created it. And comparing it to the seemingly boundless possibilities – and attendant threats to intellectual property as an economic model – offered by the Internet. And once I’d thought it through, I stopped wanting to author books.

I’m 27. I write well. I have plenty to say. I ought to be the ‘future of the book’. But I want to introduce myself on if:book by proposing that perhaps the future of the book is not a future of books. Or at least it’s not one of authorship, but of writing. Now, please don’t get me wrong: I don’t think print publishing has nothing to offer. I’m an English graduate. I like the physicality of books, the way you can annotate them, the way they start conversations or act as a currency among friends. But I feel deeply that the print industry is out of step with the contemporary cultural landscape, and will not produce the principal agents in the future of that landscape. And I’m not sure that ebooks will, either. My hunch is that things are going two ways: writers as orchestrators of mass creativity, or writers as wielders of a new rhetoric.

Collaborative writing experiments such as Charles Leadbeater’s We-Think venture begin to explore some of the potential open to writers willing to share authorship with an open-sided group, and able to handle the tools that facilitate that kind of work.

Perhaps less obviously, the Elizabethans knew that telling stories changed the cultural landscape, and used that for political purposes. But we live – at least ostensibly – with the Enlightenment notion that storytelling is not political, and that the only proper medium for political discussion is reasoned argument. And yet, the literary theories of Sidney are the direct ancestors of the modern PR and marketing landscape. Today’s court poets work in PR.

What, then, happens when writers choose to operate outside the strictures of the print industry (or the PR copywriting serfdom that claims many of them at the moment) and become instead court poets for the cultural, social, political interest groups of their choice? What happens when we reclaim rhetoric from the language of ‘rationality’ and ‘detachment’? Can we do that honestly, and in the service of humanity?

I find myself involved in both kinds: writing as orchestration/quality control, and writing as activist tool. But in both cases, I remain unsatisfied by the print industry’s feedback loop of three to five years from conception to publication. So instead, I co-write screenplays, proposals, updates. I write emails to my collaborators; I blog about what I’m up to; I tell stories designed to reproduce virally via the ‘Forward’ button. Perhaps foolishly, I still dream of changing the world by writing. And I want to be around when it happens.