The other day, I came across an interesting experiment with a new model of distribution and ownership on the web, something that writers, publishers and journalists should pay attention to. KeepMedia charges $4.95 a month for unlimited access to 200 mainstream periodicals (see list) spanning the last 12 years up to the present day. That’s significantly less than what I pay annually for my handful of print periodical subscriptions, and gives me access to much more material (kind of like LexisNexis for the masses). Plus, you do get to “keep” – that’s part of how it works (indeed, their logo is a kangaroo with a stack of magazines stuffed in her pouch). KeepMedia allows you to attach notes to articles and to store away “clippings.” It also makes it easy to track subjects across publications, and has automated recommendations for related stories. I assume that stored articles will get caged off if you stop subscribing. That’s what makes me nervous about the pay-for-the-service model. You don’t actually get to keep anything for the long haul, unless you print it out. But KeepMedia suggests one way that newspapers and publishers might adapt to the digital age.

The other day, I came across an interesting experiment with a new model of distribution and ownership on the web, something that writers, publishers and journalists should pay attention to. KeepMedia charges $4.95 a month for unlimited access to 200 mainstream periodicals (see list) spanning the last 12 years up to the present day. That’s significantly less than what I pay annually for my handful of print periodical subscriptions, and gives me access to much more material (kind of like LexisNexis for the masses). Plus, you do get to “keep” – that’s part of how it works (indeed, their logo is a kangaroo with a stack of magazines stuffed in her pouch). KeepMedia allows you to attach notes to articles and to store away “clippings.” It also makes it easy to track subjects across publications, and has automated recommendations for related stories. I assume that stored articles will get caged off if you stop subscribing. That’s what makes me nervous about the pay-for-the-service model. You don’t actually get to keep anything for the long haul, unless you print it out. But KeepMedia suggests one way that newspapers and publishers might adapt to the digital age.

Right now, publishers are still stuck on the idea of individual “copies.” The web – an enormous, interconnected copying machine – is inherently hostile to this idea. So publishers generally insist on digital rights management (DRM) – coded controls that restrict what you can do with a piece of media. This, almost invariably, is infuriating, and ends up unfairly punishing people who have willingly paid a fair price for an item. Pay-for-the-service models won’t solve the problem entirely, but they do get away from the idea of “copies.” On the web, copies are cheap, or free. But access to a library or database is valuable. It’s not about how many copies are sold, it’s about how many people are reading. So charge at the gate. Once people are inside, it’s all you can eat. This is nothing new. People play a flat rate for cable television, which is essentially a list of publications. You pay extra for premium channels, or pay-per-view special features, but your basic access is assured. What and how much you watch is up to you. Yahoo! is trying this right now for music. Why not do the same for newspapers, or for books? The web is combining publishing with broadcasting. Publishers and broadcasters need to adapt.

Related posts:

“web news as gated community”

“self-destructing books”

Category Archives: Publishing, Broadcast, and the Press

LA Times to run “wikatorials”

Next week, as part of a general reworking of its editorial page, the LA Times is staring “wikatorials” – “an online feature that will empower you to rewrite Los Angeles Times editorials.”

(via Dan Gillmor)

UPDATE: “Upheaval on Los Angeles Time Editorial Pages” in NY Times.

web news as gated community

Just found out about this on diglet.. Launched in April, The National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP) is a joint effort of the Library of Congress and the National Endowment of the Humanities to create a comprehensive web archive of the nation’s public domain newspapers.

Ultimately, over a period of approximately 20 years, NDNP will create a national, digital resource of historically significant newspapers from all the states and U.S. territories published between 1836 and 1922. This searchable database will be permanently maintained at the Library of Congress (LC) and be freely accessible via the Internet.

(A similar project is getting underway in France.)

It’s frustrating that this online collection will stop at 1922. Ordinary libraries maintain up-to-date periodical archives and make them available to anyone if they’re willing to make the trip. But if they put those collections on the web, they’ll be sued. Archives are one of the few ways newspapers have figured out to make money on the web, so they’re not about to let libraries put their microfilm and periodical reading rooms online. The paradigm has flipped.. in print, you pay for the current day’s edition, but the following day it ends up in the trash, or wrapping a fish. The passage of 24 hours makes it worthless. On the web, most news is free. It’s the fish wrap that costs you.

The web has utterly changed what things are worth. For most people, when a news site asks them to pay, they high tail it out of there and never look back. Even being asked to register is enough to deter many readers. But come September, the New York Times will start charging a $50 annual fee for what it considers its most unique commodities – editorials, op-eds, and selected other features. Is a full subscription site not far off? With their prestige and vast readership, the Times might be able to pull it off. But smaller papers are afraid to start charging, even as they watch their print circulation numbers plummet. If one paper puts up a tollbooth, they instantly become irrelevant to millions of readers. There will always be a public highway somewhere nearby.

A friend at the Columbia School of Journalism told me that the only way newspapers can be profitable on the web is if they all join together in some sort of league and charge bulk subscription fees for universal access. If there’s a wholesale move to the pay model, then readers will have no choice but to shell out. It will be like paying for cable service, where each newspaper is a separate channel. The only time you register is when you pay the initial fee. From then on, it’s clear sailing.

It’s a compelling idea, but could just be collective suicide for the newspapers. There will always be free news on offer somewhere. Indian and Chinese wire services might claim the market while the prestigious western press withers away. Or people will turn to state-funded media like the BBC or Xinhua. Then again, people might be willing to pay if it means unfettered access to high quality, independent journalism. And with newspapers finally making money on web subscriptions, maybe they’d start loosening up about their archives.

remixing the news

There’s been an explosion of creative tinkering since the BBC opened up its API (applications programming interface) last month. An API is a window into a site’s code and content allowing techie types to build new applications with BBC material. It’s really worth going over to the BBC Backstage blog to take a look at the first batch of prototypes and demos. The majority are clever splicings of BBC data – news, traffic reports, images etc. – with Google Maps (everyone’s favorite lately), not unlike chicagocrime.org. Other notable examples: an RSS feed of BBC complaints; a feature that allows you to tag articles and read tags left by other readers; and a nice “tag soup” visualization of financial news.

Correction: A reader kindly pointed out that BBC Backstage hasn’t actually released APIs yet (though they intend to soon). The projects I’ve referenced use BBC feeds, or have scraped content directly from the BBC site. APIs are to follow soon (more info here). When they do, the scaping process will become much cleaner. For now, the BBC welcomes projects that “use our stuff to build your stuff” the rough-and-tumble way, and is happy to showcase them on the Backstage site.

The API is becoming a powerful tool for creative reinvention of the web. Back in April, I wrote about Dan Gillmor’s piece on “Web 3.0”.. Web 1.0 was the early web, a place you went to read – a series of interconnected brochures. Web 2.0 is the “read-write” web – it’s a place you go to interact. Web 3.0 is where we start weaving the disparate pieces into new forms. APIs let you do this. You take one application and design a new front end that shows your point of view. Or you take two applications and mix them together, creating something new and illuminating. Right now, Web 2.0 is pretty well in place. The tools for self-expression and interaction are pretty accessible – email, chat, blogs, etc. But the weaving tools required for 3.0 are available only to advanced users. We’ll see if that changes.

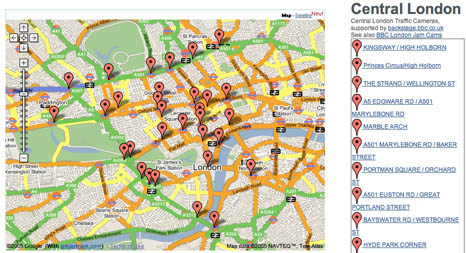

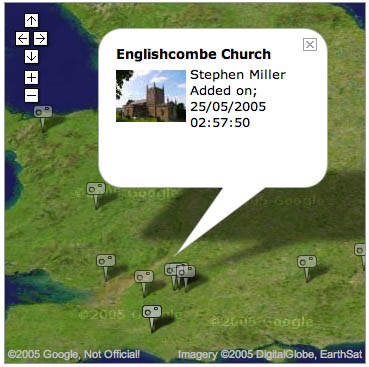

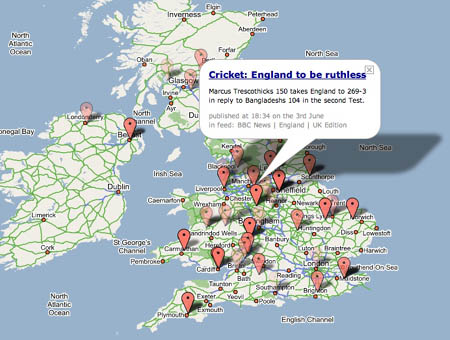

Here are grabs from four of the map prototypes at BBC Backstage:

Traffic Maps:

Map of BBC London Jam Cams:

Photo Mapping:

Map of the News:

For more analysis, check out this article on O’Reilly Radar.

the city writes its book

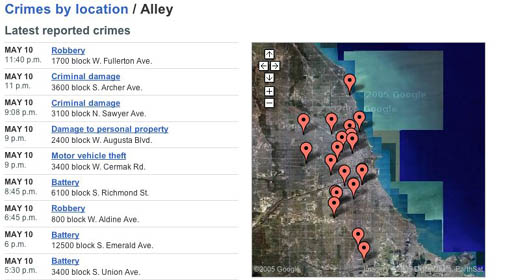

chicagocrime.org, the best use of Google Maps I’ve seen to date, has been making the web rounds over the past week. It generates maps using information scraped from Citizen ICAM, a public portal to the Chicago Police Department’s database of reported crime. You can view by type of crime, street, date, police district, location type (i.e. alley, ATM, residence etc.), or a map of the whole city.

This is the latest in a series of living documents that have sprung up recently – web spaces tied by a thousand strings to real, physical places. I can imagine chicagocrime being integrated into a larger Chicago area web hub, or aggregator. Ideally, these hubs (see here and here) will combine the conviviality of the blog, the utility of craigslist, the diversity of Flickr or ourmedia, and the collective vigilance of citizen journalism. Other recently launched intitiatives of note are Bayosphere (“…of, by and for the Bay Area) and mnspeak.com (“twin cities: all day, all night”). The more people participate, the truer the picture of that place at that time. Are we moving past the primacy of the editor? Or will editors prove more important than ever before?

brush up your shakespeare

In Wired yesterday, Cory Doctorow sums up recent brave efforts by the BBC to adapt to a changing world: BBC Backstage, the Creative Archive, and reader-contributed photos.

“America’s entertainment industry is committing slow, spectacular suicide, while one of Europe’s biggest broadcasters — the BBC — is rushing headlong to the future, embracing innovation rather than fighting it. Unlike Hollywood, the BBC is eager and willing to work with a burgeoning group of content providers whose interests are aligned with its own: its audience.”

Above is a clip from a 1913 silent film version of Hamlet, downloadable for free from the British Film Institute under the aegis of the Creative Archive – one of the few bits of free content made available so far. It feels good to make a video quotation with total impunity. Perhaps others will be inspired to take a page from BBC’s book.

Here also is Rick Prelinger‘s speech to the Creative Archive Seminar in April. Prelinger is one of America’s great activist archivists.

NY Times chipping away at free content

Starting in September, the NY Times will charge an annual subscription fee for a “Select” service, including editorials, op-eds, and archives. Basic news content will remain free. Times chair Arthur Sulzberger Jr remarked that though online advertising is undergoing exponential growth, it is just a matter of time until it flattens out and assumes regular cycles, like in print advertising. Is the free content joyride gradually coming to an end? Or is the Times pounding nails into its own coffin?

incredible shrinking newspaper

Facing slipping circulation and massive migration to the web by younger news consumers, a number of top tier newspapers are switching from the traditional broadsheet format to the more handy tabloid, including the European and Asian editions of the Wall Street Journal.

But is this enough? One British advertiser remarks: “We want newspapers to come up with a solution to the threat of marginalization in a digitalized world. But they have to do more than just play around with the size of paper they’re printed on.”

The International Herald Tribune ran this story yesterday. I’ve plugged it before, but the IHT is noteworthy as one of the few online newspapers to eschew vertical scrolling for the layout of articles. Instead, they have simple, attractive (and I would argue, much more readable) horizontal scrolling across fixed, three-column plates. With its long vertical fields, you might say that web news, too, is stuck in the broadsheet model. The problem is that, unlike a print newspaper, a computer screen can’t be folded to improve readability, or to isolate a desired area of the page.

your news, your pictures

“If you find yourself in the right place at the right time, if an event is unfolding before your eyes and you capture it on a camera or mobile phone, either as a photograph or video, then please send it to BBC News.”

“If you find yourself in the right place at the right time, if an event is unfolding before your eyes and you capture it on a camera or mobile phone, either as a photograph or video, then please send it to BBC News.”

The BBC has just made a bold move into user-generated, or rather user-augmented, news. If anyone thinks that a community-built media is only being explored on a smaller, local scale (see here and here), then think again. The world is in a frenzied state of self-documentation – laying down a vast mosaic of images, video, graphics and text on top of every inch of reality. If the mainstream media is to keep up, it will have to a certain extent “employ” everyone as stringers. To put a slight spin on Shirky‘s formulation: the only group that can record everything is everybody.

(image: Andrew Vorobyov’s photo of the “orange revolution” in Ukraine)

poor circulation

Newspapers continue their slide.. From an article in WSJ (a rare free feature):

“Rather than simply trying to halt the decline, which can be done readily through discounts and promotions, they’re being forced to try to “manage” their circulation in new ways. Some publishers are deliberately cutting circulation in the hope of selling advertisers on the quality of their subscribers. Others are expanding into new markets to make up for losses in their core markets. Some are switching to a tabloid format or giving away papers to try to attract younger readers. Others are pouring money into television and radio advertising and expensive face-to-face sales pitches to potential subscribers.”

You’d think some of this desperate energy could be channeled into making newspapers live more fully on the web.