I was on the underground making my way to the London Book Fair yesterday, hoping to stand out from the crowds of frantic publishers jostling there by carrying over my shoulder the fabulously pretentious “Proust Society of America” book bag which I bought on a trip to New York for a meeting at the Mercantine Library, but was disconcerted to notice that the man on the other side of the carriage was staring at me strangely, then eventually he lent over and said to me, “Have you read Proust?” to which I replied yes I had, most of it, but many, many years ago, at which this gentleman told me that on his retirement he had made a list of classics he hadn’t read, and In Search of Lost Time was top of it so he has since read it six times, on permanent rotation, breaking off between volumes for other novels and recently he’s been looking for a Proust close reading group, has scoured the internet for such a thing, had found the New York group but nothing like it in London; then we arrived at Holborn Station and he stepped off the train before I could ask to swap email addresses, not because I want to start a close reading Proust group, but… well, perhaps he’ll Google his way to this page, and perhaps some other London Proust lovers will too and then I can put them in touch with each other and so the Marcel Proust Underground Networked Book Group will be born.

Category Archives: proust

finishing things

One of the most interesting things about the emerging online forms of discourse is how they manage to tear open all our old assumptions. Even if new media hasn’t yet managed to definitively change the rules, it has put them into contention. Here’s one, presented as a rhetorical question: why do we bother to finish things?

The importance of process is something that’s come up again and again over the past two years at the Institute. Process, that is, rather than the finished work. Can Wikipedia ever be finished? Can a blog be finished? They could, of course, but that’s not interesting: what’s fascinating about a blog is its emulation of conversation, it’s back-and-forth nature. Even the unit of conversation – a post on a blog, say – may never really be finished: the author can go back and change it, so that the post you viewed at six o’clock is not the post you viewed at four o’clock. This is deeply frustrating to new readers of blogs; but in time, it becomes normal.

* * * * *

But before talking about new media, let’s look at old media. How important is finishing things historically? If we look, there’s a whole tradition of things refusing to be finished. We can go back to Tristram Shandy, of course, at the very start of the English novel: while Samuel Richardson started everything off by rigorously trapping plots in fixed arcs made of letters, Laurence Sterne’s novel, ostensibly the autobiography of the narrator, gets sidetracked in cock and bull stories and disasters with windows, failing to trace his life past his first year. A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy, Sterne’s other major work of fiction, takes the tendency even further: the narrative has barely made it into France, to say nothing of Italy, before it collapses in the middle of a sentence at a particularly ticklish point.

There’s something unspoken here: in Sterne’s refusal to finish his novels in any conventional way is a refusal to confront the mortality implicit in plot. An autobiography can never be finished; a biography must end with its subject’s death. If Tristram never grows up, he can never die: we can imagine Sterne’s Parson Yorrick forever on the point of grabbing the fille de chambre‘s ———.

Henry James on the problem in a famous passage from The Art of the Novel:

Really, universally, relations stop nowhere, and the exquisite problem of the artist is eternally but to draw, by a geometry of his own, the circle within which they shall happily appear to do so. He is in the perpetual predicament that the continuity of things is the whole matter, for him, of comedy or tragedy; that this continuity is never, by the space of an instant or an inch, broken, or that, to do anything at all, he has at once intensely to consult and intensely to ignore it. All of which will perhaps pass but for a supersubtle way of pointing the plain moral that a young embroiderer of the canvas of life soon began to work in terror, fairly, of the vast expanse of that surface.

But James himself refused to let his novels – masterpieces of plot, it doesn’t need to be said – be finished. In 1906, a decade before his death, James started work on his New York Edition, a uniform selection of his work for posterity. James couldn’t resist the urge to re-edit his work from the way it was originally published; thus, there are two different editions of many of his novels, and readers and scholars continue to argue about the merits of the two, just as cinephiles argue about the merits of the regular release and the director’s cut.

This isn’t an uncommon issue in literature. One notices in the later volumes of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu that there are more and more loose ends, details that aren’t quite right. While Proust lived to finish his novel, he hadn’t finished correcting the last volumes before his death. Nor is death necessarily always the agent of the unfinished: consider Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. David M. Levy, in Scrolling Forward: Making Sense of Documents in the Digital Age, points out the problems with trying to assemble a definitive online version of Whitman’s collection of poetry: there were a number of differing editions of Whitman’s collection of poems even during his life, a problem compounded after his death. The Whitman Archive, created after Levy wrote his book, can help to sort out the mess, but it can’t quite work at the root of the problem: we say we know Leaves of Grass, but there’s not so much a single book by that title as a small library.

The great unfinished novel of the twentieth century is Robert Musil’s The Man without Qualities, an Austrian novel that might have rivaled Joyce and Proust had it not come crashing to a halt when Musil, in exile in Switzerland in 1942, died from too much weightlifting. It’s a lovely book, one that deserves more readers than it gets; probably most are scared off by its unfinished state. Musil’s novel takes place in Vienna in the early 1910s: he sets his characters tracing out intrigues over a thousand finished pages. Another eight hundred pages of notes suggest possible futures before the historical inevitability of World War I must bring their way of life to an utter and complete close. What’s interesting about Musil’s notes are that they reveal that he hadn’t figured out how to end his novel: most of the sequences he follows for hundreds of pages are mutually exclusive. There’s no real clue how it could be ended: perhaps Musil knew that he would die before he could finish his work.

* * * * *

The visual arts in the twentieth century present another way of looking at the problem of finishing things. Most people know that Marcel Duchamp gave up art for chess; not everyone realizes that when he was giving up art, he was giving up working on one specific piece, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. Duchamp actually made two things by this name: the first was a large painting on glass which stands today in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Duchamp gave up working on the glass in 1923, though he kept working on the second Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, a “book” published in 1934: a green box that contained facsimiles of his working notes for his large glass.

Duchamp, despite his protestations to the contrary, hadn’t actually given up art. The notes in the Green Box are, in the end, much more interesting – both to Duchamp and art historians – than the Large Glass itself, which he eventually declared “definitively unfinished”. Among a great many other things, Duchamp’s readymades are conceived in the notes. Duchamp’s notes, which he would continue to publish until his death in 1968, function as an embodiment of the idea that the process of thinking something through can be more worthwhile than the finished product. His notes are why Duchamp is important; his notes kickstarted most of the significant artistic movements of the second half of the twentieth century.

Duchamp’s ideas found fruit in the Fluxus movement in New York from the early 1960s. There’s not a lot of Fluxus work in museums: a good deal of Fluxus resisted the idea of art as commodity in preference to the idea of art as process or experience. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece is perhaps the most well known Fluxus work and perhaps exemplary: a performer sits still while the audience is invited to cut pieces of cloth from her (or his) clothes. While there was an emphasis on music and performance – a number of the members studied composition with John Cage – Fluxus cut across media: there were Fluxus films, boxes, and dinners. (There’s currently a Fluxus podcast, which contains just about everything.) Along the way, they also managed to set the stage for the gentrification of SoHo.

There was a particularly rigorous Fluxus publishing program; Dick Higgins helmed the Something Else Press, which published seminal volumes of concrete poetry and artists’ books, while George Maciunas, the leader of Fluxus inasmuch as it had one, worked as a graphic designer, cranking out manifestos, charts of art movements, newsletters, and ideas for future projects. Particularly ideas for future projects: John Hendricks’s Fluxus Codex, an attempt to catalogue the work of the movement, lists far more proposed projects than completed ones. Owen Smith, in Fluxus: The History of an Attitude, describes a particularly interesting idea, an unending book:

This concept developed out of Maciunas’ discussions with George Brecht and what Maciunas refers to in several letters as a “Soviet Encyclopedia.” Sometime in the fall of 1962, Brecht wrote to Maciunas about the general plans for the “complete works” series and about his own ideas for projects. In this letter Brecht mentions that he was “interested in assembling an ‘endless’ book, which consists mainly of a set of cards which are added to from time to time . . . [and] has extensions outside itself so that its beginning and end are indeterminate.” Although the date on this letter is not certain, it was sent after Newsletter No. 4 and prior to the middle of December when Maciunas responded to it.} This idea for a expandable box is later mentioned by Maciunas as being related to “that of Soviet encyclopedia – which means not a static box or encyclopedia but a constantly renewable – dynamic box.”

Maciunas and Brecht never got around to making their Soviet encyclopedia, but it’s an idea that might resonate more now than in did in 1962. What they were imagining is something that’s strikingly akin to a blog. Blogs do start somewhere, but most readers of blogs don’t start from the beginning: they plunge it at random and keep reading as the blog grows and grows.

* * * * *

One Fluxus-related project that did see publication was An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, a book credited to Daniel Spoerri, a Romanian-born artist who might be best explained as a European Robert Rauschenberg if Rauschenberg were more interested in food than paint. The basis of the book is admirably simple: Spoerri decided to make a list of everything that was on his rather messy kitchen table one morning in 1961. He made a map of all the objects on his not-quite rectangular table, numbered them, and, with the help of his friend Robert Filliou, set about describing (or “anecdoting”) them. From this simple procedure springs the magic of the book: while most of the objects are extremely mundane (burnt matches, wine stoppers, an egg cup), telling how even the most simple object came to be on the table requires bringing in most of Spoerri’s friends & much of his life.

Having finished this first version of the book (in French), Spoerri’s friend Emmett Williams translated into English. Williams is more intrusive than most translators: even before he began his translation, he appeared in a lot of the stories told. As is the case with any story, Williams had his own, slightly different version of many of the events described, and in his translation Williams added these notes, clarifying and otherwise, to Spoerri’s text. A fourth friend, Dieter Roth, translated the book into German, kept Williams’s notes and added his own, some as footnotes of footnotes, generally not very clarifying, but full of somewhat related stories and wordplay. Spoerri’s book was becoming their book as well. Somewhere along the line, Spoerri added his own notes. As subsequent editions have been printed, more and more notes accrete; in the English version of 1995, some of them are now eight levels deep. A German translation has been made since then, and a new French edition is in the works, which will be the twelfth edition of the book. The text has grown bigger and bigger like a snowball rolling downhill. In addition to footnotes, the book has also gained several introductions, sketches of the objects by Roland Topor, a few explanatory appendices, and an annotated index of the hundreds of people mentioned in the book.

Part of the genius of Spoerri’s book is that it’s so simple. Anyone could do it: most of us have tables, and a good number of those tables are messy enough that we could anecdote them, and most of us have friends that we could cajole into anecdoting our anecdotes. The book is essentially making something out of nothing: Spoerri self-deprecatingly refers to the book as a sort of “human garbage can”, collecting histories that would be discarded. But the value of of the Topography isn’t rooted in the objects themselves, it’s in the relations they engender: between people and objects, between objects and memory, between people and other people, and between people and themselves across time. In Emmett Williams’s notes on Spoerri’s eggshells, we see not just eggshells but the relationship between the two friends. A network of relationships is created through commenting.

George LeGrady seized on the hypertextual nature of the book and produced, in 1993, his own Anecdoted Archive of the Cold War. (He also reproduced a tiny piece of the book online, which gives something of a feel for its structure.) But what’s most interesting to me isn’t how this book is internally hypertextual: plenty of printed books are hypertextual if you look at them through the right lens. What’s interesting is how its internal structure is mirrored by the external structure of its history as a book, differing editions across time and language. The notes are helpfully dated; this matters when you, the reader, approach the text with thirty-odd years of notes to sort through, notes which can’t help being a very slow, public conversation. There’s more than a hint of Wikipedia in the process that underlies the book, which seems to form a private encyclopedia of the lives of the authors.

And what’s ultimately interesting about the Topography is that it’s unfinished. My particular copy will remain an autobiography rather than a biography, trapped in a particular moment in time: though it registers the death of Robert Filliou, those of Dieter Roth and Roland Topor haven’t yet happened. Publishing has frozen the text, creating something that’s temporarily finished.

* * * * *

We’re moving towards an era in which publishing – the inevitable finishing stroke in most of the examples above – might not be quite so inevitable. Publishing might be more of an ongoing process than an event: projects like the Topography, which exists as a succession of differing editions, might become the norm. When you’re publishing a book online, like we did with Gamer Theory, the boundaries of publishing become porous: there’s nothing to stop you from making changes for as long as you can.

learning to read

Somebody interviewed Bob for a documentary a few months ago. I don’t remember who this was, because I was in the other room busy with something else, but I was half-listening to what was being discussed: how the book is changing, what precisely the Institute does, in short, what we discuss from day to day on this blog. One statement captured my ear: Bob offhandedly declared that “we don’t really know how to read Wikipedia yet”. I made a note of it at the time; since then I’ve been periodically pulling his statement out at idle moments and rolling it over and over in my mind like a pebble in my pocket, trying to decide exactly what it could mean.

Somebody interviewed Bob for a documentary a few months ago. I don’t remember who this was, because I was in the other room busy with something else, but I was half-listening to what was being discussed: how the book is changing, what precisely the Institute does, in short, what we discuss from day to day on this blog. One statement captured my ear: Bob offhandedly declared that “we don’t really know how to read Wikipedia yet”. I made a note of it at the time; since then I’ve been periodically pulling his statement out at idle moments and rolling it over and over in my mind like a pebble in my pocket, trying to decide exactly what it could mean.

There’s something appealing to me about the flatness of the statement: “We don’t really know how to read Wikipedia yet.” It’s obvious but revelatory: the reason that we find the Wikipedia frustrating is that we need to learn how to read it. (By we I mean the reading public as a whole. Perhaps you have; judging from the arguments that fly back and forth, it would seem that the majority of us haven’t.) The problem is, of course, that so few people actually bother to state this sort of thing directly and then to unpack the repercussions of it.

What’s there to learn in reading the Wikipedia? Let’s start with a sample sentence from the entry on Marcel Proust:

In addition to the grief that attended his mother’s death, Proust’s life changed due to a very large inheritance (in today’s terms, a principal of about $6 million, with a monthly income of about $15,000).

Criticizing the Wikipedia for being poorly written is like shooting fish in a barrel, but bear with my lack of sportsmanship for a second. Imagine that you found the above sentence in a printed reference work. A printed reference book that seems to be written in the voice of a sixth grade student deeply interested in matters financial might worry you. It would worry me. It’s worried many critics of the Wikipedia, who point out that this clearly isn’t the sort of manicured prose we’re used to reading in books and magazines.

But this prose is also conceptually different. A Wikipedia article is not constructed in the same way that a magazine article is written. Nor is the content of a Wikipedia article at one particular instant in time – content that has probably been different, and might certainly change – analogous to the content of a print magazine article, which is always, from the moment of printing, exactly the same. If we are to keep using the Wikipedia, we’ll have to get used to the solecisms endemic there; we’ll also need to readjust they way we give credence to media. (Right now I’m going to tiptoe around the issue of text and authority, which is of course an enormous can of worms that I’d prefer not to open right now.) But there’s a reason that the above quotation shouldn’t be that worrying: it’s entirely possible, and increasingly probable as time goes on, that when you click the link above, you won’t be able to find the sentence I quoted.

This faith in the long run isn’t an easy thing, however. When we read Wikipedia we tend to apply to it the standards of judgment that we would apply to a book or magazine, and it often fails by these standards, as might be expected. When we’re judging Wikipedia this way, we presuppose that we know what it is formally: that it’s the same sort of thing as the texts we know. This seems arrogant: why should we assume that we already know how to read something that clearly behaves differently from the text we’re used to? We shouldn’t, though we do: it’s a human response to compare something new to something we already know, but often when we do this, we miss major formal differences.

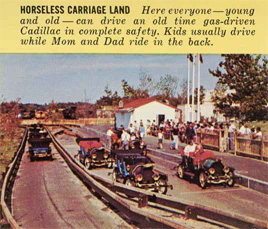

This isn’t the best way to read something new. It’s akin to the “horseless carriage” analogy that Ben’s used: when you think of a car as a carriage without a horse, you miss whatever it is that makes a car special. But there’s a problem with that metaphor, in that it carries with it ideas of displacement. Evolution is often perceived as being transformative: one thing turns into, and is then replaced by, another, as the horse was replaced by the car for purposes of transportation. But it’s usually more of a splitting: there’s a new species as well as the old species from which it sprung. The old species may go extinct, or it may not. To finish that example: we still have horses.

This isn’t the best way to read something new. It’s akin to the “horseless carriage” analogy that Ben’s used: when you think of a car as a carriage without a horse, you miss whatever it is that makes a car special. But there’s a problem with that metaphor, in that it carries with it ideas of displacement. Evolution is often perceived as being transformative: one thing turns into, and is then replaced by, another, as the horse was replaced by the car for purposes of transportation. But it’s usually more of a splitting: there’s a new species as well as the old species from which it sprung. The old species may go extinct, or it may not. To finish that example: we still have horses.

Figuratively, what’s happened with the Wikipedia is that a new species of text has arisen and we’re still wondering why it won’t eat the apples we’re proffering it. The Wikipedia hasn’t replaced print encyclopedias; in all probability, the two will coexist for a while. But I don’t think we yet know how to read Wikipedia. We judge it by what we’re used to, and everyone loses. Were you to judge a car by a horse’s attributes, you wouldn’t expect to have an oil crisis in a century.

Perhaps a useful way to think about this: a few paragraphs of Proust, found on a trip through In Search of Lost Time with Bob’s statement bouncing around my head. The Guermantes Way, the third part of the book, feels like the longest: much of this volume is about failing to recognize how things really are. Proust’s hapless narrator alternately recognizes his own mistakes of judgment and makes new ones for six hundred pages, with occasional flashes of insight, like this reflection:

. . . . There was a time when people recognized things easily when they were depicted by Fromentin and failed to recognize them at all when they were painted by Renoir.

Today people of taste tell us that Renoir is a great eighteenth-century painter. But when they say this they forget Time, and that it took a great deal of time, even in the middle of the nineteenth century, for Renoir to be hailed as a great artist. To gain this sort of recognition, an original painter or an original writer follows the path of the occultist. His painting or his prose acts upon us like a course of treatment that is not always agreeable. When it is over, the practitioner says to us, “Now look.” And at this point the world (which was not created once and for all, but as often as an original artist is born) appears utterly different from the one we knew, but perfectly clear. Women pass in the street, different from those we used to see, because they are Renoirs, the same Renoirs we once refused to see as women. The carriages are also Renoirs, and the water, and the sky: we want to go for a walk in a forest like the one that, when we first saw it, was anything but a forest – more like a tapestry, for instance, with innumerable shades of color but lacking precisely the colors appropriate to forests. Such is the new and perishable universe that has just been created. It will last until the next geological catastrophe unleashed by a new painter or writer with an original view of the world.

(The Guermantes Way, pp.323–325, trans. Mark Treharne.) There’s an obvious comparison to be made here, which I won’t belabor. Wikipedia isn’t Renoir, and its entry for poor Eugène Fromentin, whose paintings are probably better left forgotten, is cribbed from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. But like the gallery-goers who needed to learn to look at Renoir, we need to learn to read Wikipedia, to read it as a new form that certainly inherits some traits from what we’re used to reading, but one that differs in fundamental ways. That’s a process that’s going to take time.

object nostalgia

I’ve buckled down and decided that, as I never really play them any more & I’m tired of dragging their crates from apartment to apartment, it’s time to rip all my old CDs and get rid of the physical detritus. I’ve been doing this slowly, taking the opportunity to listen to them all again, which draws me to the inexorable conclusion that I’ve bought an awful lot of bad music over the years. At what point did I decide that I needed the entire recorded output of the Telstar Ponies? how many CDs by The Fall does any one person really need? whatever happened to my Joy Division box set? But it’s interesting handling the CDs as objects: for the majority, I can remember where they were acquired and sometimes the circumstances that I listened to them in. As an exercise in personal archaeology, I’ve been writing down what I remember.

It’s self-indulgent, a nostalgic activity. Proust, the particular lens through which I’ve been looking at the world lately, explains the experience quite nicely, but with books:

This is because things – a book in its red binding, like all the rest – at the moment we notice them, turn within us into something immaterial, akin to all the preoccupations or sensations we have at that particular time, and mingle indissolubly with them. Some name, read long ago in a book, contains among its syllables the strong wind and bright sunlight of the day when we were reading it.

(p. 193 of Ian Patterson’s translation of Finding Time Again.) This is also a more eloquent version of the image evoked near the end of what’s become almost a standard script, the conversation that I fall into when explaining my job to someone new. “No, the Institute is not going to be taking your books away,” I assure people. “Good,” they say, “my books are special.” And then I’m told exactly why their books are special, which generally has to do with the same constellation of nostalgia, memory, and personal history that’s cohered around my old CDs. With books, it’s solidified to be almost a critical tradition, one of the primary arguments leveled against electronic attempts at replicating the functionality of books. Sven Birkerts pioneered this approach, and it’s since been picked up by most would-be defenders of the book. The most recent I’ve read is that of William Gass titled “A Defense of the Book,” in A Temple of Texts, his latest collection of essays; it’s a title that could serve for any number of essays standing firm against anti-nostalgists.

The core of these arguments is this: that our nostalgia towards books indicates an ineffable quality of the book as an object that can’t be digitally replicated. It’s a vague argument at best; as such, it’s a difficult one to dispute. Often it’s simply brushed aside: condescending to nostalgia isn’t a worthy use of the technologist’s time. But it’s usually a stopping point in arguments about digitalization, and as such it bears scrutiny.

The passage I quoted above from Proust is a useful tool for the job. The background: this is an episode in the last volume of Proust’s novel. At this moment he happens to pick up a book that his mother read to him as a child, George Sand’s François le champi. The book transports him into a cascade of memories, and then into reflection on how memory works, and how objects get tangled in the skeins of our memory. The trigger of memory is of particular interest; here, Proust seizes upon the problem of materiality. Is it the book itself, or the words in the book? The first sentence suggests the former: the red binding of the book has an aura about it. But the second sentence, with its crisp images, suggests that the content of the book, the forgotten name on the page, is what’s really important.

There’s something else interesting here which doesn’t usually get remarked upon, though this is a famous image in Proust’s work: the book that the narrator picks up isn’t the book he read as a childhood. It’s another copy of the same book. He’s not in his childhood home, but rather in the library at the house of a friend, and this is another copy of François le champi. In all probability, the binding of the book he picks up (made, as he notes, to match all the other books in the library) is different to the binding of the book he picked up as a child. It’s worth noting that it’s the syllables of the spoken (even silently) word – does a word on a page have syllables? – that contain memory.

In a way, this makes perfect sense: the madeline that the narrator dips in tea in the beginning of the novel is obviously not the same madeline that he dipped in tea as a small child. But in a way, Proust is illustrating what might be the central artistic crisis of the twentieth century, the problem of human response to mechanical reproduction. It’s a problem that falls squarely into the category of “job description” at the Institute.

To the rescue: another Marcel, Duchamp, comes to mind, an artist whose body of work seems to have been created with an eye to preparing us to live in an age where originals are lost in a sea of copies, an age in which, as Marx & Engels predicted, “all that is solid melts into air.” With Duchamp begins the idea of the multiple: many instances of the same work of art like the many copies of a book that can be printed or the many photographic prints that could be made from a negative. “The idea of multiples is the distribution of ideas,” said Joseph Beuys. In one sense, Duchamp’s introduction of the multiple is art catching up with Gutenberg; in another, it’s a carefully orchestrated shift in values between the concrete and the virtual.

What can Duchamp teach us about nostalgia? His work carefully separates artistic value from the enclosing objects. Take, as an example, Duchamp’s famous readymades – the urinal, the bicycle wheel, the snow shovel, etc. Although his urinal has been described as the single greatest work of art of the twentieth century, it no longer exists: like the originals of most of his other readymades, it seems to have mysteriously disappeared at some point. There are, however, an unending parade of copies. Duchamp made his own miniature copies of them for his Box in a Valise, his autosummarization of his career as an artist. He happily authorized Arturo Schwartz to create his own copies of his readymades. At the Whitney Biennial right now, Sturtevant has taken it upon herself to make her own copies of the readymades. Duchamp, were he still alive, would probably cheerfully add these to his procession of simulacra.

The artist’s thought, Duchamp declared, is more important than the object to which it is attached: the object of art serves is a container for the thought of the artist (just as the book is a container for the text within). As viewers of art, we should concentrate, Duchamp thought, on the idea behind what we see, not what we see. Moreover, he argued, this is what had always been the value of art. In an interview with Alain Jouffroy in 1964 he classified painting into two varieties, the kind

intended only for the retina . . . and the kind of painting which reaches beyond the retina, using the paint tube as its springboard for reaching much farther. This was the case with the religious painters of the Renaissance. The paint tube didn’t interest them. What interested them was the idea of expressing the divine in one form or another. Without wanting to do the same, I maintain that pure painting as an aim in itself is of no import. My aim is something completely different: for me, in consists in a combination, or at least in an expression, which only the grey cells can reproduce.

He saw his work, of course, as aspiring to be the latter sort of art. Recent history would seem to bear out the avowedly atheist Duchamp enlisting the religious painters of the Renaissance in his camp: one of Schwarz’s copies of his urinal was recently attacked with a hammer as if it were Michaelangelo’s Pietà.

As odd as Duchamp considering himself as among the religious painters might be my recruitment of Proust against object-nostalgia. Proust is generally perceived as glorying in the past: his novel is about the process of looking backwards. But this isn’t entirely justified: note this passage from Finding Time Again, which occurs shortly after the episode quoted above:

Some used to say that art in a period of speed and haste would be brief, like the people before the war who predicted that it would be over quickly. The railway was thus supposed to have killed contemplative thought, and it was vain to long for the days of the stage-coach, but now the automobile fulfils their function and once again sets the tourists down in front of abandoned churches.

(p.197.) This comes startlingly close to language we use regularly at the Institute (the trope of the horseless carriage and so on). New technology doesn’t kill art or thought: it changes it, and change itself is morally neutral. And again: like the object of the book, the stage-coach and the automobile are both vehicles, both means to an end. We shouldn’t feel nostalgia for the vehicle: we’re using it to get somewhere, and there are other ways to get to the same end. Proust shouldn’t be construed as saying that the march of progress is entirely a good thing: people might stop visiting the abandoned churches. But it would be foolish to imagine that people stopped visiting the abandoned churches because they abandoned stage-coaches for automobiles.

To go back to where I started from: my decision to chuck my CDs doesn’t seem that strange: plenty of other people are doing the same thing. Though vinyl records seems to function, for those older than myself, as reservoirs of nostalgia, music would seem to have firmly wandered into the realm of the digital. Could we care about DVDs? HD-DVDs? It doesn’t seem that likely. It’s more useful to have these things in object-free form: if an album’s on my hard drive, I’ll probably listen to it more often than if its a CD in a crate under my bed. Nor am I really adding CDs to the crate: while I’m still happily consuming music, I’m buying most of it in digital form from places like http://www.kompakt-mp3.net.

A caveat: I’m not trying to make a universal argument. I’m not throwing out all my CDs: certain objects do have very personal associations (those given as gifts, for example). (And Duchamp, a man who relished self-contradiction, would probably have recognized this: he took extraordinary precautions to save his work.) But I don’t think that we should imagine that nostalgia is explicitly a function of the container, be that container the CD or the book. A book is, after all, a multiple, a mass-produced object. Nostalgia’s not built in at the press: it’s something that we put into our books. There are exceptions (an artist’s book produced for a hand-picked audience, for example), but that exceptionality should be recognized as part of their value and not taken for granted.

And a coda: if humanity outlasts the book, nostalgia will outlast the book, which it preceded. It’s codified perfectly in this fragment (translated by Guy Davenport) of the Greek poet Archilochos, who was born around 680 B.C.E., died around 645 B.C.E. and probably never saw a book in his life:

How many times,

How many times,

On the gray sea,

The sea combed

By the wind

Like a wilderness

Of woman’s hair,

Have we longed,

Lost in nostalgia,

For the sweetness

Of homecoming.