London-based creative studio and social think-tank Proboscis has put impressive effort into thinking through the incarnations and reincarnations of written material between printed and digitized forms. Diffusion, one of Proboscis’ recent-ish ventures, is a technology that lays out short texts in a form that enables them to be printed off and turned, with a few cuts and folds, into easily-portable pamphlets.

For now, it’s still in beta, though I hear from Proboscis founder Giles Lane that they’re aiming to make this technology more widely available. Meanwhile, Proboscis is using Diffusion to produce Short Work, a series of downloadable public-domain texts selected and introduced by guests. Works so far include three essays by Samuel Johnson, selected by technology critic and journalist Bill Thompson; Common Sense by Thomas Paine, selected by Worldchanging editor Alex Steffen; and Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism, selected by myself.

Though the Short Work pieces are not exclusively from the same period, it’s interesting to note that all these guest selections date from the eighteenth century. It can’t be simply that these texts are most likely to be a) short, and b) in the public domain (though this no doubt has something to do with it). But the eighteenth century saw an explosion in printing, outdone only by the new textual explosion of the Web, and the political, intellectual and critical voices that emerged from that Babel of print raise many questions about the ongoing evolution of our current digital discourse.

Category Archives: print_on_demand

not just websites

At a meeting of the Interaction Designer’s Association (IxDA) one of the audience members, during the Q&A, asked “Why are we all making websites?”

What a fantastic question. We primarily consider the digital at the Institute, and the way that discourse is changing as it is presented on screen and in the network. But the question made me reevaluate why a website is the form I immediately think of for any new project. I realized that I have a strong predilection for websites because I love the web, and I know what I’m doing when it comes to sites. But that doesn’t mean a site is always the right form for every project. It prompted me to reconsider two things: the benefit of Sophie books, and the position of print in light of the network, and what transformations we can make to the printed page.

First, the Sophie book. It’s not a website, but it is part of the network. During the development and testing of a shared, networked book, we discovered that there a particular feeling of intimacy associated with sharing Sophie book. Maybe it’s our own perspective on Sophie that created the sensation, but sharing a Sophie book was not like giving out a url. It had more meaning than that. The web seemed like a wide-open parade ground compared to the cabin-like warmth of reading a Sophie book across the table from Ben. Sophie books have borders, and there was a sense of boundedness that even tightly designed websites lack. I’m not sure where this leads yet, but it’s a wonderfully humane aspect of the networked book that we haven’t had a chance to see until now.

On to print. One idea for print that I find fascinating, though deeply problematic, is the combination of an evolving digital text with print-on-demand (POD) in a series of rapidly versioned print runs. A huge issue comes up right away: there is potentially disastrous tension between a static text (the printed version) and the evolving digital version. Printing a text that changes frequently will leave people with different versions. When we talked about this at the Institute, the concern around the table was that any printed version would be out of date as soon as the toner hit the page. And, since a book is supposed to engender conversation, this book, with radical differences between versions, would actually work against that purpose. But I actually think this is a benefit from our point of view—it emphasizes the value of the ongoing conversation in a medium that can support it (digital), and highlights the limitations of a printed text. At the same time it provides a permanent and tangible record of a moment in time. I think there is value in that, like recording a live concert. It’s only a nascent idea for an experiment, but I think it will help us find the fulcrum point between print and the network.

As a rider, there is a design element with every document (digital or print) that makes the most of the originating process and creates a beautiful final product. So a short, but difficult question: What is the ideal form for a rapidly versioned document?

time out and some of what went into it

A remaindered link that I keep forgetting to post. A couple of weeks back, Time Out London ran a nice little “future of books” feature that makes mention of the Institute. A good chunk of it focuses on On Demand Books, the Espresso book machine and the evolution of print, but it also manages to delve a bit into networked territory, looking at Penguin’s wiki novel project and including a few remarks from me about the yuckiness of e-book hardware and the social aspects of text. Leading up to the article, I had some nice conversations over email and phone with the writer Jessica Winter, most of which of course had no hope of fitting into a ~1300-word piece. And as tends to be the case, the more interesting stuff ended up on the cutting room floor. So I thought I’d take advantage of our laxer space restrictions and throw up for any who are interested some of that conversation.

(Questions are in bold. Please excuse rambliness.)

The other day I was having an interesting conversation with a book editor in which we were trying to determine whether a book is more like a table or a computer; i.e., is a book a really good piece of technology in its present form, or does it need constant rethinking and upgrades, or is it both? Another way of asking this question: Will the regular paper-and-glue book go the way of the stone tablet and the codex, or will it continue to coexist with digital versions? (Sorry, you must get asked this question all the time…)

We keep coming back to this question is because it’s such a tricky one. The simple answer is yes.

The more complicated answer…

When folks at the Institute talk about “the book,” we’re really more interested in the role the book historically has played in our civilization — that is, as the primary vehicle humans use for moving around ideas. In this sense, it seems pretty certain that the future of the book, or to put it more awkwardly, the future of intellectual discourse, is shifting inexorably from printed pages to networked screens.

Predicting hardware is a tougher and ultimately less interesting pursuit. I guess you could say we’re agnostic: unsure about the survival or non-survival of the paper-and-glue book as we are about the success or failure of the latest e-book reading device to hit the market. Still, there’s this strong impulse to try to guess which forms will prevail and which will go extinct. But if you look at the history of media you find that things usually aren’t so clear cut.

It’s actually quite seldom the case that one form flat out replaces another. Far more often the two forms go on existing together, affecting and changing one other in a variety of ways. Photography didn’t kill painting as many predicted it would. Instead it caused a crisis that led to Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism. TV didn’t kill radio but it did usurp radio’s place at the center of the culture and changed the sorts of programming that it made sense for radio to deliver. So far the Internet hasn’t killed TV but there’s no question that it’s bringing about a radical shift in both the production and consumption of television, blurring the line between the two.

The Internet probably won’t kill off books either but it will almost certainly affect what sorts of books get produced, and on the ways in which we read and write them. It’s happening already. Books that look and feel much the same way today as they looked and felt 30 years ago are now almost invariably written on computers with word processing applications, and increasingly, researched or even written on the Web.

Certain things that we used to think of as books — encyclopedias, atlases, phone directories, catalogs — have already been reinvented, and in some cases merged. Other sorts of works, particularly long-form narratives, seem to have a more durable relationship with the printed word. But even here, our relationship with these books is changing as we become more accustomed to new networked forms. Continuous partial attention. Porous boundaries between documents and media. Social and participatory forms of reading. Writing in public. All these things change the very idea of reading and writing, so when you resume an offline mode of doing these things, your perceptions and way of thinking have likely changed.

(A side note. I think this experience of passage back and forth between off and online forms, between analog and digital, is itself significant and for people in our generation, with our general background, is probably the defining state of being. We’re neither immigrant or native. Or to dip into another analogical pot, we’re amphibians.)

As time and technology progress and we move with increasing fluidity between print and digital, we may come to better appreciate the unique affordances of the print book. Looked at one way, the book is an outmoded technology. It lacks the interactivity and interconnectedness of networked communication and is extremely limited in scope when compared with the practically boundless universe of texts and media that exists online. But you could also see this boundedness is its greatest virtue — the focus and structure it brings, enabling sustained thought and contemplation and private intellectual growth. Not to mention archival stability. In these ways the book is a technology that would be hard to improve upon.

John Updike has said that books represent “an encounter, in silence, of two minds.” Does that hold true now, or will it continue to as we continue to rethink the means of production (both technological and intellectual) of books? What are the advantages and disadvantages of a networked book over a book traditionally conceived in that “silent encounter”?

I think I partly answered this question in the last round. But again, as with media forms, so too with ways of reading. Updike is talking about a certain kind of reading, the kind that is best suited to the sorts of things he writes: novels, short stories and criticism. But it would be a mistake to apply this as a universal principle for all books, especially books that are intended as much, if not more, as a jumping off point for discussion as for that silent encounter.

Perhaps the biggest change being brought about by new networked forms of communication is the redefinition of the place of the individual in relation to the collective. The present publishing system very much favors the individual, both in the culture of reverence that surrounds authors and in the intellectual property system that upholds their status as professionals. Updike is at the top of this particular heap and so naturally he defends it as though it were the inviolable natural order.

Digital communication radically clashes with this order: by divorcing intellectual property from physical property (a marriage that has long enabled the culture industry to do business) and by re-situating textual communication in the network, connecting authors and readers in startling ways that rearrange the traditional hiearchies.

What do you think of print-on-demand technology like the Espresso machine? One quibble that I have with it, and it’s probably a lost cause, is that it seems part of the death of browsing (which is otherwise hastened by the demise of the independent bookstore and the rise of the “drive-through” library); opportunities for a chance encounter with a book seem to be lessened. Just curious–has the Institute addressed the importance of browsing at all?

The serendipity of physical browsing would indeed be unfortunate to lose, and there may be some ways of replicating it online. North Carolina State University uses software called Endeca for their online catalog where you pull up a record of a book and you can look at what else is next to it on the physical shelf. But generally speaking browsing in the network age is becoming a social affair. Behavior-derived algorithms are one approach — Amazon’s collaborative filtering system, based on the aggregate clickstreams and purchasing patterns of its customers, is very useful and getting better all the time. Then there’s social bookmarking. There, taxonomy becomes social, serendipity not just a chance encounter with a book or document, but with another reader, or group of readers.

And some other scattered remarks about conversation and the persistent need for editors:

Blogging, comments, message boards, etc… In some ways, the document as a whole is just the seed for the responses. It’s pointing toward a different kind of writing that is more dialogical, and we haven’t really figured it out yet. We don’t yet know how to manage and represent complex conversations in an electronic environment. From a chat room to a discussion forum to a comment stream in a blog post, even to an e-mail thread or a multiparty instant-messaging conversation–it’s just a list of remarks, a linear transcript that flattens the discussion’s spirals, loops and pretzels into a single straight line. In other words, the minute the conversation becomes complex, we become unable to make that complexity readable.

We’ve talked about setting up shop in Second Life and doing an experiment there in modeling conversations. But I’m more interested in finding some way of expanding two-dimensional interfaces into 2.5. We don’t yet know how to represent conversations on a screen once it crosses a certain threshold of complexity.

People gauge comment counts as a measure of the social success of a piece of writing or a video clip. If you look at Huffington Post, you’ll see posts that have 500 comments. Once it gets to that level, it’s sort of impenetrable. It makes the role of filters, of editors and curators–people who can make sound selections–more crucial than ever.

Until recently, publishing existed as a bottleneck model with certain material barriers to publishing. The ability to overleap those barriers was concentrated in a few bottlenecks, with editorial filters to choose what actually got out there. Those material barriers are no longer there; there’s still an enormous digital divide, but for the 1 billion or so people who are connected, those barriers are incredibly low. There’s suddenly a super-abundance of information with no gatekeeper; instead of a bottleneck, we have a deluge. The act of filtering and selecting it down becomes incredibly important. The function that editors serve in the current context will be need to be updated and expanded.

google and the future of print

Veteran editor and publisher Jason Epstein, the man who first introduced paperbacks to American readers, discusses recent Google-related books (John Battelle, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, David Vise etc.) in the New York Review, and takes the opportunity to promote his own vision for the future of publishing. As if to reassure the Updikes of the world, Epstein insists that the “sparkling cloud of snippets” unleashed by Google’s mass digitization of libraries will, in combination with a radically decentralized print-on-demand infrastructure, guarantee a bright future for paper books:

[Google cofounder Larry] Page’s original conception for Google Book Search seems to have been that books, like the manuals he needed in high school, are data mines which users can search as they search the Web. But most books, unlike manuals, dictionaries, almanacs, cookbooks, scholarly journals, student trots, and so on, cannot be adequately represented by Googling such subjects as Achilles/wrath or Othello/jealousy or Ahab/whales. The Iliad, the plays of Shakespeare, Moby-Dick are themselves information to be read and pondered in their entirety. As digitization and its long tail adjust to the norms of human nature this misconception will cure itself as will the related error that books transmitted electronically will necessarily be read on electronic devices.

Epstein predicts that in the near future nearly all books will be located and accessed through a universal digital library (such as Google and its competitors are building), and, when desired, delivered directly to readers around the world — made to order, one at a time — through printing machines no bigger than a Xerox copier or ATM, which you’ll find at your local library or Kinkos, or maybe eventually in your home.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Epstein has founded a new company, OnDemand Books, to realize this vision, and earlier this year, they installed test versions of the new “Espresso Book Machine” (pictured) — capable of producing a trade paperback in ten minutes — at the World Bank in Washington and (with no small measure of symbolism) at the Library of Alexandria in Egypt.

Epstein is confident that, with a print publishing system as distributed and (nearly) instantaneous as the internet, the codex book will persist as the dominant reading mode far into the digital age.

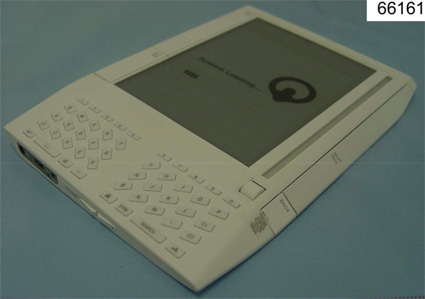

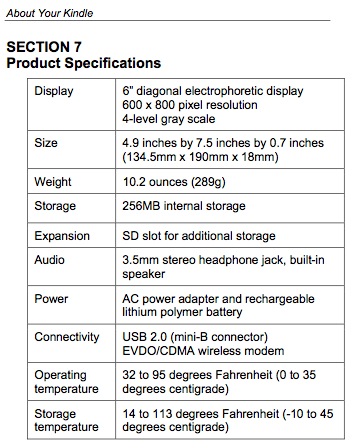

amazon looks to “kindle” appetite for ebooks with new device

Engadget has uncovered details about a soon-to-be-released upcoming/old/bogus(?) Amazon ebook reading device called the “Kindle,” which appears to have an e-ink display, and will presumably compete with the Sony Reader. From the basic specs they’ve posted, it looks like Kindle wins: it’s got more memory, it’s got a keyboard, and it can connect to the network (update: though only through the EV-DO wireless standard, which connects Blackberries and some cellphones; in other words, no basic wifi). This is all assuming that the thing actually exists, which we can’t verify.

Regardless, it seems the history of specialized ebook devices is doomed to repeat itself. Better displays (and e-ink is still a few years away from being really good) and more sophisticated content delivery won’t, in my opinion, make these machines much more successful than their discontinued forebears like the Gemstar or the eBookMan.

Ebooks, at least the kind Sony and Amazon will be selling, dwell in a no man’s land of misbegotten media forms: pale simulations of print that harness few of the possibilities of the digital (apparently, the Sony Reader won’t even have searchable text!). Add highly restrictive DRM and vendor lock-in through the proprietary formats and vendor sites made for these devices and you’ve got something truly depressing.

Publishers need to get out of this rut. The future is in networked text, multimedia and print on demand. Ebooks and their specialized hardware are a red herring.

Teleread also comments.

physical books and networks 2

Much of our time here is devoted to the extreme electronic edge of change in the arena of publishing, authorship and reading. For some, it’s a more distant future than they are interested in, or comfortable, discussing. But the economics and means/modes of production of print are being no less profoundly affected — today — by digital technologies and networks.

The Times has an article today surveying the landscape of print-on-demand publishing, which is currently experiencing a boom unleashed by advances in digital technologies and online commerce. To me, Lulu is by far the most interesting case: a site that blends Amazon’s socially networked retail formula with a do-it-yourself media production service (it also sponsors an annual “Blooker” prize for blog-derived books). Send Lulu your book as a PDF and they’ll produce a bound print version, in black-and-white or color. The quality isn’t superb, but it’s cheap, and light years ahead of where print-on-demand was just a few years back. The Times piece mentions Lulu, but focuses primarily on a company called Blurb, which lets you design books with customized software called BookSmart, which you can download free from their website. BookSmart is an easy-to-learn, template-based assembly tool that allows authors to assemble graphics and text without the skills it takes to master professional-grade programs like InDesign or Quark. Blurb books appear to be of higher quality than Lulu’s, and correspondingly, more expensive.

Reading this reminded me of an email I received about a month back in response to my “Physical Books and Networks” post, which looked at authors who straddle the print and digital worlds. It came from Abe Burmeister, a New York-based designer, writer and artist, who maintains an interesting blog at Abstract Dynamics, and has also written a book called Economies of Design and Other Adventures in Nomad Economics. Actually, Burmeister is still in the midst of writing the book — but that hasn’t stopped him from publishing it. He’s interested in process-oriented approaches to writing, and in situating acts of authorship within the feedback loops of a networked readership. At the same time, he’s not ready to let go of the “objectness” of paper books, which he still feels is vital. So he’s adopted a dynamic publishing strategy that gives him both, producing what he calls a “public draft,” and using Lulu to continually post new printable versions of his book as they are completed.

Reading this reminded me of an email I received about a month back in response to my “Physical Books and Networks” post, which looked at authors who straddle the print and digital worlds. It came from Abe Burmeister, a New York-based designer, writer and artist, who maintains an interesting blog at Abstract Dynamics, and has also written a book called Economies of Design and Other Adventures in Nomad Economics. Actually, Burmeister is still in the midst of writing the book — but that hasn’t stopped him from publishing it. He’s interested in process-oriented approaches to writing, and in situating acts of authorship within the feedback loops of a networked readership. At the same time, he’s not ready to let go of the “objectness” of paper books, which he still feels is vital. So he’s adopted a dynamic publishing strategy that gives him both, producing what he calls a “public draft,” and using Lulu to continually post new printable versions of his book as they are completed.

His letter was quite interesting so I’m reproducing most of it:

Using print on demand technology like lulu.com allows for producing printed books that are continuously being updated and transformed. I’ve been using this fact to develop a writing process loosely based upon the linux “release early and release often” model. Books that essentially give the readers a chance to become editors and authors a chance to escape the frozen product nature of traditional publishing. It’s not quite as radical an innovation as some of your digital and networked book efforts, but as someone who believes there always be a particular place for paper I believe it points towards a subtly important shift in how the books of the future will be generated.

…one of the things that excites me about print on demand technology is the possibilities it opens up for continuously evolving books. Since most print on demand systems are pdf powered, and pdfs have a degree of programability it’s at least theoretically possible to create a generative book; a book coded in such a way that each time it is printed an new result comes out. On a more direct level though it’s also very practically possible for an author to just update their pdf’s every day, allowing for say a photo book to contain images that cycle daily, or the author’s photo to be a web cam shot of them that morning.

When I started thinking about the public drafting process one of the issues was how to deal with the fact that someone might by the book and then miss out on the content included in the edition that came out the next day. Before I received my first hard copies I contemplated various ways of issuing updated chapters and ways to decide what might be free and what should cost money. But as soon as I got that hard copy the solution became quite clear, and I was instantly converted into the Cory Doctrow/Yochai Benkler model of selling the book and giving away the pdf. A book quite simply has a power as an object or artifact that goes completely beyond it’s content. Giving away the content for free might reduce books sales a bit (I for instance have never bought any of Doctrow’s books, but did read them digitally), but the value and demand for the physical object will still remain (and I did buy a copy of Benkler’s tome.) By giving away the pdf, it’s always possible to be on top of the content, yet still appreciate the physical editions, and that’s the model I have adopted.

And an interesting model it is too: a networked book in print. Since he wrote this, however, Burmeister has closed the draft cycle and is embarking on a total rewrite, which presumably will become a public draft at some later date.

rice university press reborn digital

After lying dormant for ten years, Rice University Press has relaunched, reconstituting itself as a fully digital operation centered around Connexions, an open-access repository of learning modules, course guides and authoring tools.  Connexions was started at Rice in 1999 by Richard Baraniuk, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and has since grown into one of the leading sources of open educational content — also an early mover into the Creative Commons movement, building flexible licensing into its publishing platform and allowing teachers and students to produce derivative materials and customized textbooks from the array of resources available on the site.

Connexions was started at Rice in 1999 by Richard Baraniuk, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and has since grown into one of the leading sources of open educational content — also an early mover into the Creative Commons movement, building flexible licensing into its publishing platform and allowing teachers and students to produce derivative materials and customized textbooks from the array of resources available on the site.

The new ingredient in this mix is a print-on-demand option through a company called QOOP. Students can order paper or hard-bound copies of learning modules for a fraction of the cost of commercial textbooks, even used ones. There are also some inexpensive download options. Web access, however, is free to all. Moreover, Connexions authors can update and amend their modules at all times. The project is billed as “open source” but individual authorship is still the main paradigm. The print-on-demand and for-pay download schemes may even generate small royalties for some authors.

The Wall Street Journal reports. You can also read these two press releases from Rice:

“Rice University Press reborn as nation’s first fully digital academic press”

“Print deal makes Connexions leading open-source publisher”

UPDATE:

Kathleen Fitzpatrick makes the point I didn’t have time to make when I posted this:

Rice plans, however, to “solicit and edit manuscripts the old-fashioned way,” which strikes me as a very cautious maneuver, one that suggests that the change of venue involved in moving the press online may not be enough to really revolutionize academic publishing. After all, if Rice UP was crushed by its financial losses last time around, can the same basic structure–except with far shorter print runs–save it this time out?

I’m excited to see what Rice produces, and quite hopeful that other university presses will follow in their footsteps. I still believe, however, that it’s going to take a much riskier, much more radical revisioning of what scholarly publishing is all about in order to keep such presses alive in the years to come.

questions on libraries, books and more

Last week, Vince Mallardi contacted me to get some commentary for a program he is developing for the Library Binding Institute in May. I suggested that he send me some questions, and I would take a pass at them, and post them on the blog. My hope that is, Vince, as well as our colleagues and readers will comment upon my admittedly rough thoughts I have sketched out, in response to his rather interesting questions.

1. What is your vision of the library of the future if there will be libraries?

Needless to say, I love libraries, and have been an avid user of both academic and public libraries since the time I could read. Libraries will be in existence for a long time. If one looks at the various missions of a library, including the archiving, categorization, and sharing of information, these themes will only be more relevant in the digital age for both print and digital text. There is text whose meaning is fundamentally tied to its medium. Therefore, the creation and thus preservation of physical books (and not just its digitization) is still important. Of course, libraries will look and function in a very different way from how we conceptualize libraries today.

As much as, I love walking through library stacks, I realize that it is a luxury of the North, which was made more clear to me at the recent Access to Knowledge conference my colleague and I were fortunate enough to attend. In the economic global divide of the North and South, the importance of access to knowledge supersedes my affinity for paper books. I realize that in the South, digital libraries are a much efficient use of resources to promote sustainable knowledge, and hopefully economic, growth.

2. How much will self-publishing benefit book manufacturers, indeed save them?

Recently, I have been very intrigued with the notion of Print On Demand (POD) of books. My hope is that the stigma will be removed from the so-called “vanity press.” Start-up ventures, such as LuLu.com, have the potential to allow voices to flourish, where in the past they lacked access to traditional book publishing and manufacturing.

Looking at the often cited observation that 57% of Amazon book sales comes from books in the Long Tail (here defined as the catalogue not typically available in the 100,000 books found in a B&N superstore,) I wonder if the same economic effect could be reaped in the publishing side of books. Increasing efficiency of digital production, communication, and storage, relieve economic pressures of the small run printing of books. With print on demand, costs such as maintaining inventory are removed, as well, the risk involved in estimating the demand for first runs is reduced. Similarly, as I stated in my first response, the landscape of book manufacturing will have to adapt as well. However, I do see potential for the creation of more books rather than less.

3. What co-existence do you foresee between the printed and electronic book, as co-packaged, interactive via barcodes or steganography? etc.

Paper based books will still have its role in communication in the future. Paper is still a great technology for communication. For centuries, paper and books were the dominate medium because that was the best technology available. However, with film, television, radio and now digital forms, it is not longer always true. Thus the use of print text must be based upon the decision by the author that paper is the best medium for her creative purposes. Moving books into the digital allows for forms that cannot exist as a paper book, for instance the inclusion of audio and video. I can easily see a time when an extended analysis of a Hitchcock movie will be an annotated movie, with voice over commentary, text annotation and visual overlays. These features cannot be reproduced in traditional paper books.

Rather, that try to predict specific applications, products or outcomes, I would prefer to open the discussion to a question of form. There is fertile ground to explore the relationship between paper and digital books, however it is too early for me to state exactly what that will entail. I look forward to seeing what creative interplay of print text and digital text authors will produce in the future. The co-existence between the print and electronic book in a co-packaged form will only be useful and relevant, if the author consciously writes and designs her work to require both forms. Creating a pdf of Proust’s Swann Way’s is not going to replace the print version. Likewise, printing out Moulthrop’s Victory Garden do not make sense either.

4. Can there be literacy without print? To the McLuhan Gutenberg Galaxy proposition.

Print will not fade out of existence, so the question is a theoretical one. Although, I’m not an expert in McLuhan, I feel that literacy will still be as vital in the digital age as it is today, if not more so. The difference between the pre-movable type age and the electronic age, is that we will still have the advantages of mass reproduction and storage that people did not have in an oral culture. In fact, because the marginal cost of digital reproduction is basically zero, the amount of information we will be subjected to will only increase. This massive amount of information which we will need to process and understand will only heighten the need for not only literacy, but media literacy as well.

the book is reading you

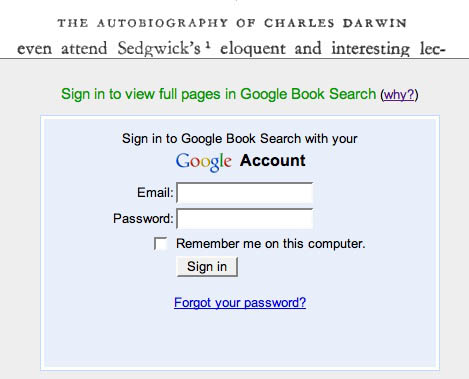

I just noticed that Google Book Search requires users to be logged in on a Google account to view pages of copyrighted works.

They provide the following explanation:

Why do I have to log in to see certain pages?

Because many of the books in Google Book Search are still under copyright, we limit the amount of a book that a user can see. In order to enforce these limits, we make some pages available only after you log in to an existing Google Account (such as a Gmail account) or create a new one. The aim of Google Book Search is to help you discover books, not read them cover to cover, so you may not be able to see every page you’re interested in.

So they’re tracking how much we’ve looked at and capping our number of page views. Presumably a bone tossed to publishers, who I’m sure will continue suing Google all the same (more on this here). There’s also the possibility that publishers have requested information on who’s looking at their books — geographical breakdowns and stats on click-throughs to retailers and libraries. I doubt, though, that Google would share this sort of user data. Substantial privacy issues aside, that’s valuable information they want to keep for themselves.

That’s because “the aim of Google Book Search” is also to discover who you are. It’s capturing your clickstreams, analyzing what you’ve searched and the terms you’ve used to get there. The book is reading you. Substantial privacy issues aside, (it seems more and more that’s where we’ll be leaving them) Google will use this data to refine Google’s search algorithms and, who knows, might even develop some sort of personalized recommendation system similar to Amazon’s — you know, where the computer lists other titles that might interest you based on what you’ve read, bought or browsed in the past (a system that works only if you are logged in). It’s possible Google is thinking of Book Search as the cornerstone of a larger venture that could compete with Amazon.

There are many ways Google could eventually capitalize on its books database — that is, beyond the contextual advertising that is currently its main source of revenue. It might turn the scanned texts into readable editions, hammer out licensing agreements with publishers, and become the world’s biggest ebook store. It could start a print-on-demand service — a Xerox machine on steroids (and the return of Google Print?). It could work out deals with publishers to sell access to complete online editions — a searchable text to go along with the physical book — as Amazon announced it will do with its Upgrade service. Or it could start selling sections of books — individual pages, chapters etc. — as Amazon has also planned to do with its Pages program.

Amazon has long served as a valuable research tool for books in print, so much so that some university library systems are now emulating it. Recent additions to the Search Inside the Book program such as concordances, interlinked citations, and statistically improbable phrases (where distinctive terms in the book act as machine-generated tags) are especially fun to play with. Although first and foremost a retailer, Amazon feels more and more like a search system every day (and its A9 engine, though seemingly always on the back burner, is also developing some interesting features). On the flip side Google, though a search system, could start feeling more like a retailer. In either case, you’ll have to log in first.