On Thursday October 9th, National Poetry Day in the UK, 2008 if:book london is launching an exciting experiment in reading and writing, supported by Arts Council England. Over the next six months I will be working with artist and web designer Toni Lebusque, project manager and film maker Sasha Hoare and a team of inspired people to create an illuminated book online, containing the poetry of William Blake, new writing, art and song inspired by Blake’s work, and the voices of many readers as they debate some of Blake’s key concerns and their relevance in the digital age.

Why Blake? Well, just imagine what William Blake’s blog would look like. Think what this radical, visionary maker and publisher of multimedia books would have made of the web.

I came across Songs of Innocence & Experience as a teenager, before teachers could convince me he was difficult. My great grandfather was a Blake scholar, and I found reproductions of the illuminated books on my grandmother’s shelves; they soon inspired me to churn out epic poems of mythical worlds, to write them out neat in an exercise book and embellish them with crayons and felt tip pens. ‘This is a world of Imagination & Vision’ he wrote, which I took to mean, ‘Go for it!’

Blake has been an inspiration to generations of real artists too, from Allen Ginsberg to Jah Wobble, a source of Imagination and Vision to all kinds of readers, yet he’s also been colonized by the academics, judged obscure on one hand, nuts on the other.

Blake railed against the treatment of Chimney Sweepers and working Londoners locked in the mind forg’d manacles of man; he conjured up vivid images of nature enhanced by symbolism and transformed by imagination; he celebrated the importance of freedom in play for children. How would he react to London now, to the digital printshop, the sweatshop and call centre, the lack of spaces for kids to roam except online? What would Blake build in Second Life’s green and pleasant land? And what digital tools might he use to make what kind of books?

Bob Stein has talked of a new kind of curatorial role involved in the publishing of tomorrow; in his Unified Theory of Publishing he writes:

“far from becoming obsolete, publishers and editors in the networked era have a crucial role to play. The editor of the future is increasingly a producer, a role that includes signing up projects and overseeing all elements of production and distribution, and that of course includes building and nurturing communities of various demographics, size, and shape. Successful publishers will build brands around curatorial and community building know-how AND be really good at designing and developing the robust technical infrastructures that underlie a complex range of user experiences.”

I agree completely, but I’m not convinced that traditional publishing companies are best placed to take on this role. I’ve spent many years working with literature organisations like the Poetry Society and Booktrust, alongside professional workers with reader development projects in libraries and the community; our trade is the creation and execution of projects which bring writers and readers together, commissioning new work for specific settings. A good arts festival sparks conversations around the themes it explores and the events it makes happen.

The Poetry Places scheme we ran at the Poetry Society in the 1990s involved residencies, workshops, performances in all kinds of venues, and the creation of poems to be engraved into a public space, proclaimed at an event, used as signage in parks, zoos and estates…

People usually classified as ‘arts administrators’ are orchestrating interactions that are much more akin to Bob’s concept of the curator of the networked book than publishers who seem to find it hard to see much beyond a downloadable replica of their traditional product.

Songs of Imagination & Digitisation will involve working with a range of those people, commissioning new writing and art, providing incentives for new voices to submit work and for readers to give us their ideas. We will mingle film, text and image, reader response and author interviews – and once we’ve gathered enough ingredients on our blog we hope to transmute them into something that feels like a proper, substantial, networked book.

So many web projects go encyclopaedic and neverending. The book of the future will be linked to a community, open to revision and extension, but also bounded in a meaningful way, a satisfying artistic entity, porous but not pointless.

if:book kicks off this project on National Poetry Day. In the morning some of us will wander round Covent Garden and Soho, where Blake was born, and talk to people about their working lives. We’ll film them reading lines from Blake, then go and drink tea while actor Toby Jones reads us Blake poems and we respond to them in doodles, written words and conversation.

And that day the inspirational Bill Thompson will release into the wild a laptop loaded up with Blake’s work. For the next five months it will be passed from person to person, each one recording their responses, and emailing them to the Songsofimaginationanddigitisation.net blog

Over the next six month’s we’ll take a psychogeographical walk to Blake’s house in South Molton Street to discuss the city, gather at the Museum of Gardening near Hercules Buildings in Lambeth where Mr & Mrs Blake naked played Adam and Eve – allegedly. We’ll go to the Sassoon Gallery near Peckham Rye where young William saw angels in the branches of trees, and discuss the innocence and experiences of childhood then and now. We will be commissioning some writers, artists and musicians, offering eReaders and iTouches to others who contribute. We hope to build an international community of readers around our blog of the project’s progress, www.songsofimaginationanddigitisation.net, including students at all levels who have Blake as a set text. We want the Songs to be a springboard into all kinds of reading.

So – Tell us what you think of this Idea; Bookmark, RSS and Del.icio.us us; Send us your Blake related Poems, Stories, Photographs and Drawings; Together Let Us Sing Songs of Imagination & Digitisation!

Category Archives: poetry

robert frost’s digital disciple

Via Ron Silliman, an interesting profile of Edmund Skellings, poet laureate of Florida since 1980 and newly appointed professor of humanities at Florida Tech. A New Englander, Skellings started off as a poet in the Robert Frost mould, and even studied under Frost at the University of Iowa in the late 50s. Around that time, however, he started experimenting with sound recordings on magnetic tape and later published a book of poems, Duels and Duets, whose covers were two vinyl recordings of Skellings voice. In 1978, Skellings discovered computers and thence embarked on a long career as an electro-poetic experimenter, combining audio recordings with digital animations of imagery and text, all the while retaining a poetic style as accessible and unadorned as Frost’s (or so the Florida Today article asserts). You can view some of digital creations on his web site. Skellings isn’t necessarily the electronic poet (or animator) for me, but his life is an interesting case study of literary and technological flux.

poem for no one

Just came across something lovely. Video for “Jed’s Other Poem (Beautiful Ground)” by the now disbanded Grandaddy from their great album The Sophtware Slump (2000). Jed is a character who weaves in and out of the album, a forlorn humanoid robot made of junk parts who eventually dies, leaving behind a few mournful poems.

Creator Stewart Smith: “I programmed this entirely in Applesoft BASIC on a vintage 1979 Apple ][+ with 48K of RAM — a computer so old it has no hard drive, mouse up/down arrow keys, and only types in capitals. First open-source music video, code available on website. Cinematography by Jeff Bernier.” A nice detail of the story is that this was originally a fan vid but was eventually adopted as the “official” video for the song.

Thanks to Alex Itin for the link!

talking of poets and sparkles

‘The cast of mind which searches, which questions, which dissents, has a great history. Each society has given it its own form: religious, literary. scientific. Much of the strength of Blake derives from the twofold form which dissent took in his time: rational and inspired… The history of dissent is not yet ended; it does not end. Men die, and societies die. They are not more lasting for being without dissent, they are more brittle: for they are purposeless, because they deny themselves a future.’

So writes Charles Bronowski in his book on William Blake, A Man Without a Mask, quoted by Shirley Dent of the Institute of Ideas in an article on the anniversary of Blake’s birth 250 years ago.

Brilliant, belligerent, barmy Blake has been claimed as a figurehead by all kinds of hippies and politicoes over the years, and was recently cited as ‘The Godfather of Psychogeography‘ by Ian Sinclair for, among other things, seeing angels in the trees of Peckham Rye and the new Jerusalem in leafy north London:

“The fields from Islington to Maylebone,

To Primrose Hill and Saint John’s Wood:

Were builded over with pillars of gold,

Are there Jerusalems pillars stood.”

(This quote from Jerusalem features in Merlin Coverley’s excellent guide to Psychogeography which includes city strollers from Defoe and Poe to Debord and Will Self).

William Blake, the man who wandered through the charter’d streets of London finding in the face of every passerby ‘marks of weakness, marks of woe’, who engraved and painted his own books of poems, selling his songs on subscription (or failing to sell them), would have made one hell of a blogger too. I imagine him mashing up maps of Hampstead with his personal mythology, forging a new kind of book on the anvil of his laptop, engaging his community of readers in fervent debate, plying them with animations of innocence and experience.

the really modern reader

Readers of this blog will probably find much of interest in Sucking on Words, a new documentary on conceptual poet Kenneth Goldsmith. Goldsmith, as I’ve noted before, is the wizard behind the curtain at ubu.com; this documentary, by Simon Morris, focuses on his work as a conceptual poet. Like much conceptual art, Goldsmith’s work tends to make many sputteringly angry; as he himself readily admits in the film, the idea of reading it can be superior to the act of reading it, and the exploration of his work in this documentary might be the best introduction to it that’s available.

A typical Goldsmith piece is to take all the text of a day’s edition of The New York Times – all of it, from the first ad to the last – and to put it into a standard book format: viewed this way, the daily paper has the heft of a typical novel. It becomes apparent from this that when we talk about “reading” a day’s New York Times, we really only mean reading a tiny subsection of the actual text in the paper. Our act of reading the paper is as much an act of ignoring. (Nor is this limited to print media; taking a typical page on the online Times, one notes that of the 963 words on the page, only 589 are the article proper: our reading of an article online entails ignoring 2/5 of the words. This quick count pays no attention to words in images, which would send the ignored quotient higher.)

Goldsmith starts from the proposition that there’s enough language in the world already. Like many in the digital age, he’s trying to find ways to make sense of it all; in a sense, he’s creating visualizations.

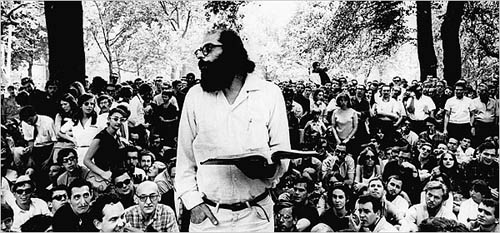

howling in the wilderness

Allen Ginsberg reading “Howl” in Washington Square in 1966. (Associated Press)

Yesterday marked the 50th anniversary of the famous court ruling in defense of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” against charges of obscenity, citing the poem’s “redeeming social importance.” The Times reports how New York radio station WBAI had the idea of airing a recording of Ginsberg reading his poem to commemorate defense, but was ultimately dissuaded by its lawyers, who feared that an increasingly zealous FCC could fine the station out of existence. The poem did end up airing freely online on pacifica.org, where where the FCC stormtroopers have no jurisdiction. There, under the banner “Howl Against Censorship,” you can still hear it with comments by Lawrence Ferlingetti and other sages of the Beat era (there’s also a link to a full online text of the poem). Worth checking out.

What’s funny and more than a little sad about this story is its utter banality. This isn’t a drag-out battle against the thought police – ?it’s censorship drained of meaning. Because Janet Jackson accidentally let a boob fly at the 2004 Super Bowl, and a few others’ assorted lewd utterances on live TV, the humorless puritans at the FCC have knuckled down into zero tolerance mode. A few incidental curse words, not the actual substance of “Howl,” seem to be at issue here, and that’s what’s truly worrisome.

In ’57, there seemed to be something real at stake concerning free speech: not in the surface indecency of Ginsberg’s language, but in the heart of his protest and lament at the whole of American civilization. The Times quotes Ferlingetti:

Mr. Ferlinghetti, 88, who owns the landmark City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, said that when “Howl” was labeled obscene, first by United States Customs agents and then by the San Francisco police, it “wasn’t really the four-letter words.” He added, “It was that it was a direct attack on American society and the American way of life.”

If anything, this latter-day episode demonstrates how our culture is on auto pilot, that we’ve become so perfunctorily litigious in the mediation of language and symbols, that the masterpiece “Howl” might as well have been a recipe for pancakes or a wall message from MySpace. The poem’s gorgeous threat has been dulled by a larger and pervading numbness. Kudos, of course, to Pacifica for trying valiantly to break through it, but even if the poem had transmitted uncensored on FM radio, or had it been some other work, ten times as damning but without a trace of profanity, would anyone have even been awake enough to receive it?

a little weekend reading

There’s an interesting post by Kenneth Goldsmith at Harriet, the blog of the Poetry Foundation about writing and the Web. Kenneth Goldsmith is probably best known – or not known? – to those who read if:book as the force behind UbuWeb; there was a fascinating interview with him recently at Archinect which provides a great deal of background on his work there. He’s also an accomplished poet; see, for example, his piece Soliloquy. In his post at Harriet, Goldsmith starts with a provocative statement: “With the rise of the web, writing has met its photography.” He argues that writing needs to redefine itself for the new parameters the Web offers; it’s a provocative argument, and one that deserves to stir up a broad discussion.

poetry in motion

I’m not sure why we didn’t note QuickMuse last year when it debuted. No matter: the concept isn’t dated and the passing year has allowed it to accrue an archive worth visiting. On the backend, QuickMuse is a project built on software by Fletcher Moore that tracks what a writer does over time; when played back, the visitor with a Javascript-enabled browser sees how the composition was written over time, sped up if desired. On the front, editor Ken Gordon has invited a number of poets to compose a poem in fifteen minutes, based, usually, on some found text. The poetry thus created isn’t necessarily the best, but that’s immaterial: it’s interesting to see how people write. (If you’d like to try this yourself, you can use Dlog.)

Composition speeds vary. Rick Moody starts writing early, making mistakes and minor corrections, but ceaselessly moving forward at a formidable clip until his fifteen minutes are up; you get the impression he could happily keep writing at the same pace for hours. The sentence “Every year South American disappears” hangs alone in Mary Jo Salter’s composition for thirty seconds; you imagine the poet turning the phrase over in her mind to find the next sentence. Lines are added, slowly, always with time passing.

What this underscores in my mind is how writing is a weirdly private act. In a sense, the reader of QuickMuse is very close to the writer, watching the poem as it unfolds; the letters appear at the exact speed at which the writer’s fingers type them in. There’s a sense of intimacy that comes with the shared time. But the thought behind the action of typing is conspicuously absent. Is the pause a pregnant moment of decision? or simply the writer not paying attention? It’s impossible to say.

translating the past

At a certain point in college, I started doing all my word processing using Adobe FrameMaker. I won’t go into why I did this – I was indulging any number of idiosyncrasies then, many of them similarly unreasonable – but I did, and I kept using FrameMaker for most of my writing for a couple of years. Even in the happiest of times, there weren’t many people who used FrameMaker; in 2001, Adobe decided to cut their losses and stop supporting the Mac version of FrameMaker, which only ran in Classic mode anyway. I now have an Intel Mac that won’t run my old copy of FrameMaker; I now have a couple hundred pages of text in files with the extension “.fm” that I can’t read any more. Could I convert these to some modern format? Sure, given time and an old Mac. Is it worth it? Probably not: I’m pretty sure there’s nothing interesting in there. But I’m still loathe to delete the files. They’re a part, however minor, of a personal archive.

This is a familiar narrative when it comes to electronic media. The Institute has a room full of Voyager CD-ROMs which we have to fire up an old iBook to use, to say nothing of the complete collection of Criterion laser discs. I have a copy of Chris Marker’s CD-ROM Immemory which I can no longer play; a catalogue of a show on Futurism that an enterprising Italian museum put out on CD-ROM similarly no longer works. Unlike my FrameMaker documents, these were interesting products, which it would be nice to look at from time to time. Unfortunately, the relentless pace of technology has eliminated that choice.

Which brings me to the poet bpNichol, and what Jim Andrews’s site vispo.com has done for him. Born Barrie Phillip Nichol, bpNichol played an enormous part in the explosion of concrete and sound poetry in the 1960s. While he’s not particularly well known in the U.S., he was a fairly major figure in the Canadian poetry world, roughly analogous to the place of Ian Hamilton Finlay in Scotland. Nichol took poetry into a wide range of places it hadn’t been before; in 1983, he took it to the Apple IIe. Using the BASIC language, Nichol programmed poetry that took advantage of the dynamic new “page” offered by the computer screen. This wasn’t the first intersection of the computer and poetry – as far back as 1968, Dick Higgins wrote a FORTRAN program to randomize the lines in his Book of Love & War & Death – but it was certainly one of the first attempts to take advantage of this new form of text. Nichol distributed the text – a dozen poems – on a hundred 5.25” floppy disks, calling the collection First Screening.

Which brings me to the poet bpNichol, and what Jim Andrews’s site vispo.com has done for him. Born Barrie Phillip Nichol, bpNichol played an enormous part in the explosion of concrete and sound poetry in the 1960s. While he’s not particularly well known in the U.S., he was a fairly major figure in the Canadian poetry world, roughly analogous to the place of Ian Hamilton Finlay in Scotland. Nichol took poetry into a wide range of places it hadn’t been before; in 1983, he took it to the Apple IIe. Using the BASIC language, Nichol programmed poetry that took advantage of the dynamic new “page” offered by the computer screen. This wasn’t the first intersection of the computer and poetry – as far back as 1968, Dick Higgins wrote a FORTRAN program to randomize the lines in his Book of Love & War & Death – but it was certainly one of the first attempts to take advantage of this new form of text. Nichol distributed the text – a dozen poems – on a hundred 5.25” floppy disks, calling the collection First Screening.

bpNichol died in 1988, about the time the Apple IIe became obsolete; four years later, a HyperCard version of the program was constructed. HyperCard’s more or less obsolete now. In 2004, Jim Andrews, Geof Huth, Lionel Kerns, Marko Niemi, and Dan Waber began a three-year process of making First Screening available to modern readers; their results are up at http://vispo.com/bp/. They’ve made Nichol’s program available in four forms: image files of the original disk that can be run with an Apple II emulator, with the original source should you want to type in the program yourself; the HyperCard version that was made in 1992; a QuickTime movie of the emulated version playing; and a JavaScript implementation of the original program. They also provide abundant and well thought out criticism and context for what Nichol did.

Looking at the poems in any version, there’s a sweetness to the work that’s immediately winning, whatever you think of concrete poetry or digital literature. Apple BASIC seems cartoonishly primitive from our distance, but Nichol took his medium and did as much as he could with it. Vispo.com’s preservation effort is to be applauded as exemplary digital archiving.

But some questions do arise: does a work like this, defined so precisely around a particular time and environment, make sense now? Certainly it’s important historically, but can we really imagine that we’re seeing the work as Nichol intended it to be seen? In his printed introduction included with the original disks, Nichol speaks to this problem:

As ever, new technology opens up new formal problems, and the problems of babel raise themselves all over again in the field of computer languages and operating systems. Thus the fact that this disk is only available in an Applesoft Basic version (the only language I know at the moment) precisely because translation is involved in moving it out further. But that inherent problem doesn’t take away from the fact that computers & computer languages also open up new ways of expressing old contents, of revivifying them. One is in a position to make it new.

Nichol’s invocation of translation seems apropos: vispo.com’s versions of First Screening might best be thought of as translations from a language no longer spoken. Translation of poetry is the art of failing gracefully: there are a lot of different ways to do it, and in each way something different is lost. The QuickTime version accurately shows the poems as they appeared on the original computer, but video introduces flickering discrepancies because of the frame rate. With the Javascript version, our eyes aren’t drawn to the craggy bitmapped letters (in a way that eyes looking at an Apple monitor in 1983 would not have been), but there’s no way to interact with the code in the way Nichol suggests because the code is different.

Nichol’s invocation of translation seems apropos: vispo.com’s versions of First Screening might best be thought of as translations from a language no longer spoken. Translation of poetry is the art of failing gracefully: there are a lot of different ways to do it, and in each way something different is lost. The QuickTime version accurately shows the poems as they appeared on the original computer, but video introduces flickering discrepancies because of the frame rate. With the Javascript version, our eyes aren’t drawn to the craggy bitmapped letters (in a way that eyes looking at an Apple monitor in 1983 would not have been), but there’s no way to interact with the code in the way Nichol suggests because the code is different.

Vispo.com’s work is quite obviously a labor of love. But it does raise a lot of questions: if Nichol’s work wasn’t so well-loved, would anyone have bothered preserving it like this? Part of the reason that Nichol’s work can be revived is that he left his code open. Given the media he was working in, he didn’t have that much of a choice; indeed, he makes it part of the work. If he hadn’t – and this is certainly the case with a great deal of work contemporary to his – the possibilities of translation would have been severely limited. And a bigger question: if vispo.com’s work is to herald a new era of resurrecting past electronic work, as bpNichol might have imagined that his work was to herald a new era of electronic poetry, where will the translators come from?

incunabula of the week

Last month, when I met the if:book crew for the first time, Ben described the net-native literary forms that have emerged to date as ‘incunabula’. I didn’t know what the word meant. He explained that, in the Middle Ages, when they first started printing books, there were all kinds of experiments which explored print technologies but hadn’t yet settled into a form that made full use of them. Ben suggested that forms of Web writing today are at an equivalent stage.

The word ‘incunabulum’ stuck with me. There’s something endearlingly fragile and tentative about it, as though Net-based forms of writing were a new species of winged things, freshly-hatched and still a bit soggy and crumpled. Since abandoning the notion of writing for print (paper) publication some time ago, though, I find myself reluctant to reinvent the wheel. So I’m very interested in what is emerging on the Net around the axis of technology and (used here in its classical sense, for want of a better word) poetry.

Top of my list at the moment as the Web’s finest emerging art form is alternate reality gaming. I wrote about that here not long ago; since then, I’ve vanished into a currently-playing ARG and will write more on the experience when I can. Meanwhile, this week I’ve stumbled across an interesting cross-section of Web-based stuff and thought I’d do a roundup here.

Disclaimer time. Ben’s already admirably dissected the problems with the Million Penguins project, so I won’t go into that. I also know there is a whole tranche of early experiments with hypertext writing which I’ve ignored. My reason for doing so is that a) I can’t be exhaustive – that’s what your search engine is for. Also, in my experience, hypertext fiction tends to be somewhat sterile and frustrating, recalling the Choose Your Own Adventure novels I read as a child. That said, if anyone knows of any that buck this trend, please send them my way.

Anyway, incunabula. The first is some years old, and is actually an event rather than a single piece of writing: the delightfully geeky Perl Poetry Contest of 2000. In the words of the Perl Journal that reviewed it:

The Perl Poetry Contest is sort of a kinder, less migraine inducing sibling of the Obfuscation Contest. The Obfuscation Contest promotes the creation of vile looking scripts. The Perl Poetry Contest is the other end of the spectrum, promoting the generation of flowing verse, and Perl, to make something beautiful.

Here’s the winner, by Angie Winterbottom:

if ((light eq dark) && (dark eq light)

&& ($blaze_of_night{moon} == black_hole)

&& ($ravens_wing{bright} == $tin{bright})){

my $love = $you = $sin{darkness} + 1;

};

It’s derived from a verse from the Pandora’s Box album ‘Original Sin’:

If light were dark and dark were light

The moon a black hole in the blaze of night

A raven’s wing as bright as tin

Then you, my love, would be darker than sin.

This is only just within my personal geek:lit frame of reference, as I don’t program Perl. But I include it in memory of the first time I heard a techie use the phrase ‘elegant code’, as I remember how struck I was then by the idea that there could be an aesthetics of machine code. I’d imagined that coding was purely functional and as such more about engineering than art; lately, I’m beginning to suspect that coders play an equivalent role in the online space to the one print authors play/ed in the literary canon. Poetry written in machine code sits elegantly across the literary/aesthetic and technical spaces in a way very suggestive of this accession of coding to the status of meta-literature.

My second incunabulum of the week comes from Everything2, a relatively open-access online writing space (see the Wikipedia entry for more info). The structures of this site merit further examination, particularly in contrast with the Million Penguins fiasco. But in the interests of brevity, for the time being here’s an entry from user “allseeingeye”: a poem about online gaming with the glorious title “im in ur base killin ur d00dz“.

I won’t go into the layers of memetic accretion around this phrase (try Encyclopedia Dramatica or urbandictionary if you really need to know). What enchanted me about the piece is that it uses a mixture of Everything2’s hard links, geek and gaming slang, and relatively traditional free verse to create something in which form and function, tradition and new technologies, “high” and “low” cultures merge most intriguingly. The writer’s genderless username addes extra ambiguity to the elision of gaming and eroticism in a way that’s very evocative of how of heightened emotion plays out in disembodied online spaces.

There’s also something thought-provoking about the fact that Everything2’s hard links are, like Wikipedia, often unfinished. If you click on one and find it incomplete, the page invites you to create an account and then add the page. When you read a poem that’s full of these sometimes-unfinished links, it’s a bit like a reverse version of The Waste Land. The difference is that where Eliot’s piece functions as an accretion of quotations that refer backwards through the history of the canon, this functions as a speculative accretion of things that may become quotations, and refers forwards to a canon not yet created.

Incunabulum number three is Batan City, a MediaWiki-based imaginary city. It was started by Paul Youlten, founder of the site formerly known as Yellowikis, a wiki-based business listings directory that sparked a legal challenge from the yellow pages industry, and now at SocialText. When Paul sent a story to a friend of his, she responded not with a commentary but with another story. The result is starting to accumulate online. There isn’t much there yet, but the convention appears to be that the “city” accumulates individually-authored stories around a central fictional place. I’m very interested in what works and does not work in wiki-based fiction (providing no structure at all, for instance, really doesn’t, as Ben pointed out a few days ago; here we have some basic structure and an invitation first to submit a story and then to spread the word to other writers. I look forward to seeing how it evolves.

Incunabulum number four is Troped, a blog-based ongoing narrative. I came across this when its author commented here in if:book, and have been dropping by there every few days to try and get a feel for what it’s up to. The format is short, not always obviously interrelated stories, usually updated every day or so. I’ll admit I haven’t been following it for long or in depth, but so far what leaps out is not a strong story, but the sense of an experiment in time and form. Individual entries, each with the feel of a mini-short-story, read down the page; but because it’s posted in blog software the chronology of the whole reads in the opposite direction. That is, the first entry in narrative terms is the last you come to in formal terms, but the direction of the entries themselves goes the other way. In addition, the author/s (perhaps unconsciously) echo/es this temporal paradox with a slightly odd use of tenses within the stories (“Jameson laughs. He preferred to just use the shop as a place to dicker around–someplace other than his house“), which adds a layer of temporal confusion. So to date I haven’t got into this one. But as a piece testing the limits and possibilities and mute formal insinuations of net-native writing delivery mechanisms, it’s certainly worth a look.

So, a mixed bag. Perl poetry experiments with the constraints of language, flirting with machine code in a way that subverts the usually functionalist preconceptions that lay non-coders such as myself tend to have about computer languages. The killin ur d00dz piece hard links within its writing community to foreground the dynamic and collaborative emergence of Web-specific jargons, even as it captures the intense experience of one individual. Batan City is a tentative (though, perhaps luckily for its creators, less populated than the Penguin effort) attempt to reconcile open editing with individual authorship of story elements, that uses the twin structures of a fictional place and an alphabetised list to structure the entries it invites. And Troped tests the interrelation between online self-publishing software and narrative temporality.

What all these pieces have in common is a concerted attempt to do more than upload the conventions of print text (boundedness, single authorship, linearity) into an environment that encourages in many ways the inverse of these traditions. They all have limitations, but all are pushing at the boundaries of what the new technologies make possible: multiple or anonymous authoring, new languages, strange temporalities and explicit acknowledgement of the intertext.