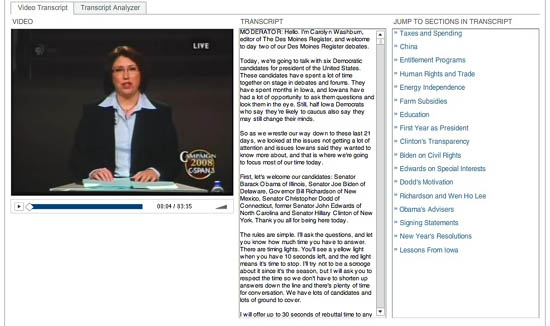

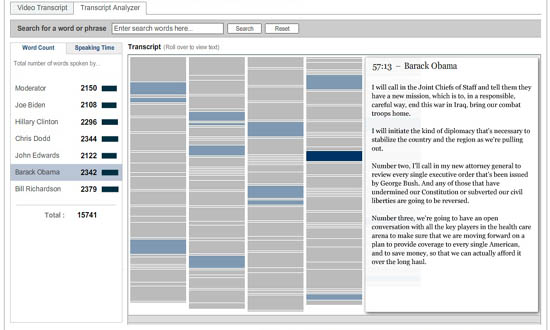

The New York Times continues to do quality interactive work online. Take a look at this recent feature that allows you to delve through video and transcript from the final Democratic presidential candidate debate in Iowa (Dec. 13, ’07). It begins with a lovely navigation tool that allows you to jump through the video topic by topic. Clicking text in the transcript (center column) or a topic from the list (right column) jumps you directly to the corresponding place in the video.

The second part is a “transcript analyzer,” which gives a visual overview of the debate. The text is laid out in miniature in a simple, clean schematic, navigable by speaker. Click a name in the left column and the speaker’s remarks are highlighted on the schematic. Hover over any block of text and that detail of the transcript pops up for you to read. You can also search the debate by keyword and see word counts and speaking times for each candidate.

These are fantastic tools -? if only they were more widely available. These would be amazing extensions to CommentPress.

Category Archives: NYTimes

ny times could open door to born-digital textbooks

Facing a far from certain future, the New York Times continues to innovate impressively, announcing yesterday a new venture in distance learning with six initial partner universities: the New York Times Knowledge Network. Among other things, this could help pave the way to a long overdue rethinking of textbooks.

Selected passages from Scott Jaschik in Inside Higher Ed:

Some of the online courses will also make use of Times content that is a centerpiece of the services being offered to colleges, on enrollment-based subscription plans. These packages will provide access to special packages of content -? summaries of articles, interactive maps, video, audio, graphs -? on a wide range of topics (the European Union, nanotechnology and so forth). Professors at institutions that subscribe would be able to make customized course Web pages, with their own content alongside these content packages. For the many topics covered on which there are updates, professors can elect to have material updated automatically or at the end of the semester.

…

Robert L. Caret, president of Towson [one of the universities participating in the Times network], said he sees the materials providing “a broader, richer educational experience to students.” He said he saw this as something Towson could do at minimal cost. The university plans to charge students the equivalent of a laboratory fee, maybe $100 to $150, for access to the Times materials. But he said student costs should not go up because he sees the online resources replacing some textbooks, and replacing them with material that is more current and more interactive.

…

Nudelman [NYT director of education] said that the Times did not view its new offerings as course-management systems in competition with Blackboard or others, but as complements to those systems. Nudelman said that the target audience for the Times for these services would be every higher education institution. “This is an absolute fit. We’ve been doing work in education for over 70 years, and this fits in with our ability to partner with the universities, colleges, and K-12, to work on distribution of information, news and entertainment, and to convene communities around credible content,” she said.

And in a comment on the IHE piece, Michael P. Lambert, Executive Director at Distance Education and Training Council, points out that the Times‘ new effort falls in a long line of continuing education programs through newspapers:

The Times entry to the distance learning field is a continuation of a tradition of “courses by newspaper” first launched in the U.S. by the Editor of the Mining Herald in Scranton, PA, in 1890. Thomas J. Foster started investigating coal mine accidents in his newspaper, and this led to a series of “instructional articles” in mine safety. His “course by newspaper” hit a nerve with the public. Soon, Foster was getting mail from around the world on the topic of mine safety, and from this editorial platform, he launched the International Correspondence Schools (ICS). By 1895, ICS had enrolled over 10,000 people in his correspondence programs, and by 1910, over 1.3 million, by 1945, over 5 million, and by 2007, over 13 million have enrolled. Today, ICS’ pioneering work in “continuing education for everyone” is carried on faithfully by Penn Foster College of Scranton, a DETC accredited distance learning institution. So there is a long and noble tradition of newspapers in bringing learning opportunities to the world, and the New York Times is a welcome entry to this tradition.

NYTimes reader

[editor’s note: The New York Times released a new software reader. It is Windows only. No Mac compatibility at this time. We asked Christine Boese, of serendipit-e.com, to post her thoughts on the matter.]

I got this off another news clip service I’m on…

NYT Finally Creates a Readable Online Newspaper (Slate)

Jack Shafer: About six months ago, I canceled my New York Times subscription because I had found the newspaper’s redesigned Web site to be superior to the print Times. I’ve now abandoned the Web version for the New York Times Reader, a new computer edition that has entered general beta release.

I went around to try to sign up for it and get a look. I couldn’t, because the Times IT dept overlooked making its beta available for Macs. I scanned through the screenshots, tho, and the comments on the blog preview of features, sneek peek #1 and #2.

Jack Shafer isn’t exactly an expert in interactive design, so I don’t know if his endorsement means anything other than, "Gee whiz, here’s a neato new thing!".

My initial impressions are that it looks like the International Herald Tribune

with a horizontal orientation I just can’t stand (the Herald Tribune often requires horizontal scrolling, and it’s far easier to read the printable version of stories). Yes, I see there is a narrow screen screenshot, but I’m thinking more about the text flow nightmares this design must cause.

But I think I have bigger reservations about the entire concept behind the Times Reader beta.

Here’s just a summary of questions I’d want answered, if I were actually able to test the beta:

- How is re-creating a facsimile of a print newspaper online a step forward for interactive media? Is it really, or is it just a kind of "horseless carriage" retrenchment? Shafer talks about some non-print-like pages that tell you what you’ve read or haven’t read, to assist browsing and search, but notes that the archives are thin. I wonder if the Times "Most Popular" feature makes the cut.

- Code. The big deal here is that it uses Microsoft .NET and advancers on Vista technology. I smell a walled garden. Is this XML-compatible? RSS-enabled? Is it even in HTML code that can be easily copied and pasted? (Shafer’s piece says it can be, but I want to see for myself) W3 validated? Does its content management system have permalinks? How do bookmarks work?

- Hyperlinks. Will the text accomodate them? Will the Times use them? Or by anchoring themselves firmly in a "reader" technology, perhaps a completely web-independent application, is the Times trying to go beyond simply a code-walled garden and also create a strong CONTENT walled garden as well? Is this a variant of TimesSelect on speed?

- Audience. Presumably the Times has some research that shows a need to court its paper-bound print-loving audience to its online products by making the online products more like the print products.

- Usability and Design. I’ve already mentioned the Mac incompatiblity. What other usability and design issues are present in this Times Reader technology? I’ll leave that to people who actually get use it.

But my question about audience is this: is there a REASON to make heroic efforts to lure print readers online? Isn’t the bigger issue trying to keep print readers attached to print, so that the ad-driven print editions don’t have to go the way of the dinosaur? The online news audience is already massive, and (Pew, Poynter) studies show that during the recent wars, large numbers of people were turning away from traditional news providers and outlets to seek out other sources of information, particularly international information, on the Internet and with news feed readers (RSS/Atom).

So in a competitive online news landscape, the Times makes a strategic turn to become more like its print product? And this will lure large numbers of online news readers back exclusively to the Times exactly HOW? Especially if it is a walled garden that doesn’t integrate well into the Blogosphere or in RSS news feed readers?

People like Terry Heaton and other media consultants (Heaton has a terrific blog, if you haven’t found it yet) are going out and telling traditional news media outlets that they have to move more strongly into an environment of UNBOUND media, to make their products more maleable for an unbound Internet environment. It appears the Times is not a company that has purchased Heaton’s services lately.

From the screenshots I’ve seen, there seems to be very little functionality or interactive user-customizable features at all. I don’t know. Color me stupid, but my gut reaction is that this is nothing more than another variant of the exact PDF version of the paper that the Times put out, only perhaps with better text searching features and dynamic text flow (meaning I’d bet it is XML-based instead of PDF-based, only with some custom-built or Microsoft-blessed walled garden DTD).

You know, for the money the Times spent on this (and the experienced journalists the Times Group laid off this past year), I’d have thought the best use of resources for a big media company would be to develop a really KILLER RSS feed reader, one that finally gets over the usability threshold that keeps feed readers in "Blinking 12-land" for most casual Internet users.

I mean, I know there are a lot of good feed readers out there (I favor Bloglines myself), but have any of you tried to convert non-techie co-workers into using a feed reader lately? I can’t for the LIFE of me figure out why there’s so much resistance to something so purely wonderful and empowering, something I believe is clearly the killer app on par with the first Mosaic browser in 1993. But because feed readers caught on bottom up instead of top down, there’s not only usability problems for the broadest audiences, there’s also a void at the top of the technology industry, by companies that fail to catch on to the RSS vision, mainly because they didn’t think it up themselves.

on business models in web publishing

Here at the Institute, we’re generally more interested in thinking up new forms of publishing than in figuring out how to monetize them. But one naturally perks up at news of big money being made from stuff given away for free. Doc Searls points to a few items of such news.

First, that latest iteration of the American dream: blogging for big bucks, or, the self-made media mogul. Yes, a few have managed to do it, though I don’t think they should be taken as anything more than the exceptions that prove the rule that most blogs are smaller scale efforts in an ecology of niches, where success is non-monetary and more of the “nanofame” variety that iMomus, David Weinberger and others have talked about (where everyone is famous to fifteen people). But there is that dazzling handful of popular bloggers that rival the mass media outlets, and they’re raking in tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of dollars in ad revenues.

Some sites mentioned in the article:

— TechCrunch: “$60,000 in ad revenue every month” (not surprising — its right column devoted to sponsors is one of the widest I’ve seen)

— Boing Boing: “on track to gross an estimated $1 million in ad revenue this year”

— paidContent.org: over a million a year

— Fark.com: “on pace to become a multimillion-dollar property.

Then, somewhat surprisingly, is The New York Times. Handily avoiding the debacle predicted a year ago by snarky bloggers like myself when the paper decided to relocate its op-ed columnists and other distinctive content behind a pay wall, the Times has pulled in $9 million from nearly 200,000 web-exclusive Times Select subscribers, while revenues from the Times-owned About.com continue to skyrocket. There’s a feeling at the company that they’ve struck a winning formula (for now) and will see how long they can ride it:

When I ask if TimesSelect has been successful enough to suggest that more material be placed behind the wall, Nisenholtz [senior vice president for digital operations] replies, “The strategy isn’t to move more content from the free site to the pay site; we need inventory to sell to advertisers. The strategy is to create a more robust TimesSelect” by using revenue from the service to pay for more unique content. “We think we have the right formula going,” he says. “We don’t want to screw it up.”

***Subsequent thought: I’m not so sure. Initial indicators may be good, but I still think that the pay wall is a ticket to irrelevance for the Times’ columnists. Their readership is large and (for now) devoted enough to maintain the modestly profitable fortress model, but I think we’ll see it wither over time.***

Also, in the Times, there’s this piece about ad-supported wiki hosting sites like Wikia, Wetpaint, PBwiki or the swiftly expanding WikiHow, a Wikipedia-inspired how-to manual written and edited by volunteers. Whether or not the for-profit model is ultimately compatible with the wiki work ethic remains to be seen. If it’s just discrete ads in the margins that support the enterprise, then contributors can still feel to a significant extent that these are communal projects. But encroach further and people might begin to think twice about devoting their time and energy.

***Subsequent thought 2: Jesse made an observation that makes me wonder again whether the Times Company’s present success (in its present framework) may turn out to be short-lived. These wiki hosting networks are essentially outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing” as the latest jargon goes, the work of the hired About.com guides. Time will tell which is ultimately the more sustainable model, and which one will produce the better resource. Given what I’ve seen on About.com, I’d place my bets on the wikis. The problem? You, or your community, never completely own your site, so you’re locked into amateur status. With Wikipedia, that’s the point. But can a legacy media company co-opt so many freelancers without pay? These are drastically different models. We’re probably not dealing with an either/or here.***

We’ve frequently been asked about the commercial potential of our projects — how, for instance, something like GAM3R 7H30RY might be made to make money. The answer is we don’t quite know, though it should be said that all of our publishing experiments have led to unexpected, if modest, benefits — bordering on the financial — for their authors. These range from Alex selling some of his paintings to interested commenters at IT IN place, to Mitch gradually building up a devoted readership for his next book at Without Gods while still toiling away at the first chapter, to McKenzie securing a publishing deal with Harvard within days of the Chronicle of Higher Ed. piece profiling GAM3R 7H30RY (GAM3R 7H30RY version 1.2 will be out this spring, in print).

Build up the networks, keep them open and toll-free, and unforseen opportunities may arise. It’s long worked this way in print culture too. Most authors aren’t making a living off the sale of their books. Writing the book is more often an entree into a larger conversation — from the ivory tower to the talk show circuit, and all points in between. With the web, however, we’re beginning to see the funnel reversed: having the conversation leads to writing the book. At least in some cases. At this point it’s hard to trace what feeds into what. So many overlapping conversations. So many overlapping economies.

corporate creep

A short article in the New York Times (Friday March 31, 2006, pg. A11) reported that the Smithsonian Institution has made a deal with Showtime in the interest of gaining an “active partner in developing and distributing [documentaries and short films].” The deal creates Smithsonian Networks, which will produce documentaries and short films to be released on an on-demand cable channel. Smithsonian Networks retains the right of first refusal to “commercial documentaries that rely heavily on Smithsonian collection or staff.” Ostensibly, this means that interviews with top personnel on broad topics is ok, but it may be difficult to get access to the paleobotanist to discuss the Mesozoic era. The most troubling part of this deal is that it extends to the Smithsonian’s collections as well. Tom Hayden, general manager of Smithsonian Networks, said the “collections will continue to be open to researchers and makers of educational documentaries.” So at least they are not trying to shut down educational uses of the these public cultural and scientific artifacts.

Except they are. The right of first refusal essentially takes the public institution and artifacts off the shelf, to be doled out only on approval. “A filmmaker who does not agree to grant Smithsonian Networks the rights to the film could be denied access to the Smithsonian’s public collections and experts.” Additionally, the qualifications for access are ill-defined: if you are making a commercial film, which may also be a rich educational resource, well, who knows if they’ll let you in. This is a blatant example of the corporatization of our public culture, and one that frankly seems hard to comprehend. From the Smithsonian’s mission statement:

The Smithsonian is committed to enlarging our shared understanding of the mosaic that is our national identity by providing authoritative experiences that connect us to our history and our heritage as Americans and to promoting innovation, research and discovery in science.

Hayden stated the reason for forming Smithsonian Networks is to “provide filmmakers with an attractive platform on which to display their work.” Yet, it was clearly stated by Linda St. Thomas, a spokeswoman for the Smithsonian, “if you are doing a one-hour program on forensic anthropology and the history of human bones, that would be competing with ourselves, because that is the kind of program we will be doing with Showtime On Demand.” Filmmakers are not happy, and this seems like the opposite of “enlarging our shared understanding.” It must have been quite a coup for Showtime to end up with stewardship of one of America’s treasured archives.

The application of corporate control over public resources follows the long-running trend towards privatization that began in the 80’s. Privatization assumes that the market, measured by profit and share price, provides an accurate barometer of success. But the corporate mentality towards profit doesn’t necessarily serve the best interest of the public. In “Censoring Culture: Contemporary Threats to Free Expression” (New Press, 2006), an essay by André Schiffrin outlines the effects that market orientation has had on the publishing industry:

As one publishing house after another has been taken over by conglomerates, the owners insist that their new book arm bring in the kind off revenue their newspapers, cable television networks, and films do….

To meet these new expectations, publishers drastically change the nature of what they publish. In a recent article, the New York Times focused on the degree to which large film companies are now putting out books through their publishing subsidiaries, so as to cash in on movie tie-ins.

The big publishing houses have edged away from variety and moved towards best-sellers. Books, traditionally the movers of big ideas (not necessarily profitable ones), have been homogenized. It’s likely that what comes out of the Smithsonian Networks will have high production values. This is definitely a good thing. But it also seems likely that the burden of the bottom line will inevitably drag the films down from a public education role to that of entertainment. The agreement may keep some independent documentaries from being created; at the very least it will have a chilling effect on the production of new films. But in a way it’s understandable. This deal comes at a time of financial hardship for the Smithsonian. I’m not sure why the Smithsonian didn’t try to work out some other method of revenue sharing with filmmakers, but I am sure that Showtime is underwriting a good part of this venture with the Smithsonian. The rest, of course, is coming from taxpayers. By some twist of profiteering logic, we are paying twice: once to have our resources taken away, and then again to have them delivered, on demand. Ironic. Painfully, heartbreakingly so.

reading fewer books

We’ve been working on our mission statement (another draft to be posted soon), and it’s given me a chance to reconsider what being part of the Institute for the Future of the Book means. Then, last week, I saw this: a Jupiter Research report claims that people are spending more time in front of the screen than with a book in their hand.

“the average online consumer spends 14 hours a week online, which is the same amount of time they watch TV.”

That is some 28 hours in front of a screen. Other analysts would say it’s higher, because this seems to only include non-work time. Of course, since we have limited time, all this screen time must be taking away from something else.

The idea that the Internet would displace other discretionary leisure activities isn’t new. Another report (pdf) from the Stanford Institute for the Quantitative Study of Society suggests that Internet usage replaces all sorts of things, including sleep time, social activities, and television watching. Most controversial was this report’s claim that internet use reduces sociability, solely on the basis that it reduces face-to-face time. Other reports suggest that sociability isn’t affected. (disclaimer – we’re affiliated with the Annenberg Center, the source of the latter report).

Regardless of time spent alone vs. the time spent face-to-face with people, the Stanford study is not taking into account the reason people are online. To quote David Weinberger:

“The real world presents all sorts of barriers that prevent us from connecting as fully as we’d like to. The Web releases us from that. If connection is our nature, and if we’re at our best when we’re fully engaged with others, then the Web is both an enabler and a reflection of our best nature.”

—Fast Company

Hold onto that thought and let’s bring this back around to the Jupiter report. People use to think that it was just TV that was under attack. Magazines and newspapers, maybe, suffered too; their formats are similar to the type of content that flourishes online in blog and written-for-the-web article format. But books, it was thought, were safe because they are fundamentally different, a special object worthy of veneration.

“In addition to matching the time spent watching TV, the Internet is displacing the use of other media such as radio, magazines and books. Books are suffering the most; 37% of all online users report that they spend less time reading books because of their online activities.”

The Internet is acting as a new distribution channel for traditional media. We’ve got podcasts, streaming radio, blogs, online versions of everything. Why, then, is it a surprise that we’re spending more time online, reading more online, and enjoying fewer books? Here’s the dilemma: we’re not reading books on screens either. They just haven’t made the jump to digital.

While there has been a general decrease in book reading over the years, such a decline may come as a shocking statistic. (Yes, all statistics should be taken with a grain of salt). But I think that in some ways this is the knock of opportunity rather than the death knell for book reading.

…intensive online users are the most likely demographic to use advanced Internet technology, such as streaming radio and RSS.

So it is ‘technology’ that is keeping people from reading books online, but rather the lack of it. There is something about the current digital reading environment that isn’t suitable for continuous, lengthy monographs. But as we consider books that are born digital and take advantage of the networked environment, we will start to see a book that is shaped by its presentation format and its connections. It will be a book that is tailored for the online environment, in a way that promotes the interlinking of the digital realm, and incorporates feedback and conversation.

At that point we’ll have to deal with the transition. I found an illustrative quote, referring to reading comic books:

“You have to be able to read and look at the same time, a trick not easily mastered, especially if you’re someone who is used to reading fast. Graphic novels, or the good ones anyway, are virtually unskimmable. And until you get the hang of their particular rhythm and way of storytelling, they may require more, not less, concentration than traditional books.”

—Charles McGrath, NY Times Magazine

We’ve entered a time when the Internet’s importance is shaping the rhythms of our work and entertainment. It’s time that books were created with an awareness of the ebb and flow of this new ecology—and that’s what we’re doing at the Institute.

the huffington post… we’re intrigued

A week after the May 9 debut of The Huffington Post, Nikki Finke delivered this bitter assessment in LA Weekly:

Judging from Monday’s horrific debut of the humongously pre-hyped celebrity blog the Huffington Post, the Madonna of the mediapolitic world has undergone one reinvention too many. She has now made an online ass of herself. What her bizarre guru-cult association, 180-degree right-to-left conversion, and failed run in the California gubernatorial-recall race couldn’t accomplish, her blog has now done: She is finally played out publicly. This website venture is the sort of failure that is simply unsurvivable. Her blog is such a bomb that it’s the movie equivalent of Gigli, Ishtar and Heaven’s Gate rolled into one. In magazine terms, it’s the disastrous clone of Tina Brown’s Talk, JFK Jr.’s George or Maer Roshan’s Radar.

Finke was not alone in her prediction of disaster. And at the time, it wasn’t so unreasonable to suspect Arianna Huffington’s experiment with celebrity group blogging might crash and burn spectacularly (The Guardian ran a very funny satire in anticipation). But by now it’s clear that not only are reports of Huffington’s death greatly exaggerated, but that something of value has been created.

The site is getting a load of traffic (a million and a half a month as of September, probably significantly more by now). As expected, it is snarky, eclectic and irreverant. What’s surprising is that Huffington’s rolodex of 250-plus occasional bloggers has managed to fill it with serious, thoughtful discussion. Many of the biggest names have failed to make much use of their soapbox (Norman Mailer has posted twice, Ellen Degeneres only once (about horses), both at the beginning of the run). What has built the site into a popular daily destination is not the promise of star-spun wisdom, but the insight provided by the more dedicated bloggers, many of them lesser-known figures with a great deal of expertise in a given area. What you end up with is a nice mix of opinion, satire, gossip, and serious analysis of current events — a kind of heightened public square.

In yesterday’s Washington Post, against the steady hum of online intrigue about Judy “run-amok” Miller, and the sound of millions of nails being gnawed in anticipation of what hopes to be a major league indictment of Rove and/or Libby, the afore-mentioned Tina Brown observed:

For Arianna Huffington, the Miller story has been to her newly birthed blog, the Huffington Post, a miniature version of what O.J. Simpson was to cable news.

And she’s right. Over this past week, something seems to have crystallized. Amidst all the head-scratching following the Times’ marathon coverage of the Judith Miller imbroglio this Sunday, the bloggers, not the press, have done the better job of cutting through the fog, or at the very least, of keeping our sights on the big picture. The Huffington Post has been particularly on the ball, with Arianna leading the way.

The big picture, of course, is that we are at war. And that The New York Times — the supposed “paper of record” — allowed itself to become part of the propaganda campaign that put us there. It’s the story of an entire news organization that, through one misguided reporter, got too “embedded” with its sources and totally lost its perspective. This is not the self-contained sort of scandal we saw with Jayson Blair. Nor is it really about some high-minded cause: the right to maintain confidentiality of sources. This is about the lies that led to war.

Unfortunately, we probably know less now about what happened with Judith Miller than we did before she delivered her mystifying testimonial on Sunday (aspens! clusters!). But the rigorous work-through the story has received around the blogosphere, and from a handful of columnists in the mainstream press, has defined the larger moral frame, keeping the democratic stakes appropriately high (hopes that the Democrats themselves might do the same will almost surely be disappointed).

In an interview with Wired last month, Huffington described what she sees as the problem with cable and online news coverage (increasingly one in the same):

The problem isn’t that the stories I care about aren’t being covered, it’s that they aren’t being covered in the obsessive way that breaks through the din of our 500-channel universe. Because those 500 channels don’t mean we get 500 times the examination and investigation of worthy news stories. It often means we get the same narrow, conventional-wisdom wrap-ups repeated 500 times. Paradoxically, in these days of instant communication and 24-hour news channels, it’s actually easier to miss information we might otherwise pay attention to. That’s why we need stories to be covered and re-covered and re-re-covered and covered again — until they filter up enough to become part of the cultural bloodstream.

The Judygate re-re-coverage on H. Post and throughout the blogosphere emphasizes the redefinition of the news as a two-way medium. The readers are now a major part of the process. What Huffington has done is to aggregate some of the more interesting readers.

it seems to be happening before our eyes

it looks like one hundred years from now history may record that 2005 was the year that big (news) media gave way to the individual voice. the intersection of the ny times/judy miller debacle with the increasing influence of the blogosphere has made us conscious of the major change taking place — RIGHT NOW.

congressman john conyers wrote today that “I find I learn more reading Arianna, Murray Waas and Lawrence O’Donnell than the New York Times or Washington Post.”

wow!

ok — it’s judy time at if:book; but i promise only future-of-the-book related comments

these thoughts came immediately after reading the NY Times’ sad attempt to explain how the “newspaper of record” managed to lose its integrity.

1. looks to me as if the media (ny times) has become the news and the blogging community are functioning as the real journalists. can anyone reading this blog, who has been following the judith miller situation say they didn’t go to the blogosphere today to get a decent handle on how to parse what the Times just did to “cover the Judith Miller” story.

2. i want a juan cole equivalent for the judy miller story; someone who specializes in the working of behind-the-scenes washington and who knows enough about law and history to put each day’s events in perpective. at the very least i want someone to present me with the ten most useful accounts on the web so that i can triangulate the problem.

3. perhaps it would be a good thought experiment to try to come up with interesting ideas of how to organize references on the web to the judith miller situation. how would you present an overview of the references?

google dystopia

Google as big brother: “Op-Art” by Randy Siegel from today’s NY Times.