![]()

Living up to its reputation as the most innovative newspaper on the web, the Guardian yesterday launched an ambitious group blogging experiment – comment is free – that brings together a broad range of public intellectual types in a daily deluge of commentary and debate. Better designed than its acknowledged model, The Huffington Post, “comment is free” consists of three columns: new posts on the left, editors’ picks in the center, and links to the Guardian’s formal opinion pages on the right.

There are a few other tidbits: a political cartoon at the bottom of the page and a photo blog. Also this small nod toward the paper’s heritage, tucked beneath the cartoon, reminding us that comment may be free…

That’s CP Scott, The Guardian’s founder and editor for its first 57 years (it should read 1821) editor of The Guardian for 57 years beginning in 1872. This ties again to Jay Rosen’s post on newspapers as “seeders of clouds.”

Category Archives: newspaper

knightfall

Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

McClatchy’s chief exec calls it: “a vote of confidence in the newspaper industry.” Or is it — to riff on the cultural environmentalism metaphor — like buying beach front property on the Aral Sea?

For a more hopeful view on the future of news, Jay Rosen (who has not yet commented on the Knight Ridder sale) has an amazing post today on Press Think about online newspapers as “seeders of clouds” and “public squares.” Very much worth a read.

two newspapers

I picked up The New York Times from outside my door this morning knowing that the lead headline was going to be wrong. I still read the print paper every morning – I do read the electronic version, but I find that my reading there tends to be more self-selecting than I’d like it to be – but lately I find myself checking the Web before settling down to the paper and a cup of coffee. On the Web, I’d already seen the predictable gloating and hand-wringing in evidence there. Because of some communication mixup, the papers went to press with the information that the trapped West Virginia coal miners were mostly alive; a few hours later it turned out that they were, in fact, mostly dead. A scrutiny of the front pages of the New York dailies at the bodega this morning revealed that just about all had the wrong news – only Hoy, a Spanish-language daily didn’t have the story, presumably because it went to press a bit earlier. At right is the front page of today’s USA Today, the nation’s most popular newspaper; click on the thumbnail for a more legible version. See also the gallery at their “newseum”. (Note that this link won’t show today’s papers tomorrow – my apologies, readers of the future, there doesn’t seem to be anything that can be done for you, copyright and all that.)

I picked up The New York Times from outside my door this morning knowing that the lead headline was going to be wrong. I still read the print paper every morning – I do read the electronic version, but I find that my reading there tends to be more self-selecting than I’d like it to be – but lately I find myself checking the Web before settling down to the paper and a cup of coffee. On the Web, I’d already seen the predictable gloating and hand-wringing in evidence there. Because of some communication mixup, the papers went to press with the information that the trapped West Virginia coal miners were mostly alive; a few hours later it turned out that they were, in fact, mostly dead. A scrutiny of the front pages of the New York dailies at the bodega this morning revealed that just about all had the wrong news – only Hoy, a Spanish-language daily didn’t have the story, presumably because it went to press a bit earlier. At right is the front page of today’s USA Today, the nation’s most popular newspaper; click on the thumbnail for a more legible version. See also the gallery at their “newseum”. (Note that this link won’t show today’s papers tomorrow – my apologies, readers of the future, there doesn’t seem to be anything that can be done for you, copyright and all that.)

At left is another front page of a newspaper, The New York Times from April 20, 1950 (again, click to see a legible version). I found it last night at the start of Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. Published in 1951, The Mechanical Bride is one of McLuhan’s earliest works; in it, he primarily looks at the then-current world of print advertising, starting with the front page shown here. To my jaundiced eye, most of the book hasn’t stood up that well; while it was undoubtedly very interesting at the time – being one of the first attempts to seriously deal with how people interact with advertisements from a critical perspective – fifty years, and billions and billions of advertisements later, it doesn’t stand up as well as, say, Judith Williamson‘s Decoding Advertisements manages to. But bits of it are still interesting: McLuhan presents this front page to talk about how Stephane Mallarmé and the Symbolists found the newspaper to be the modern symbol of their day, with the different stories all jostling each other for prominence on the page.

At left is another front page of a newspaper, The New York Times from April 20, 1950 (again, click to see a legible version). I found it last night at the start of Marshall McLuhan’s The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. Published in 1951, The Mechanical Bride is one of McLuhan’s earliest works; in it, he primarily looks at the then-current world of print advertising, starting with the front page shown here. To my jaundiced eye, most of the book hasn’t stood up that well; while it was undoubtedly very interesting at the time – being one of the first attempts to seriously deal with how people interact with advertisements from a critical perspective – fifty years, and billions and billions of advertisements later, it doesn’t stand up as well as, say, Judith Williamson‘s Decoding Advertisements manages to. But bits of it are still interesting: McLuhan presents this front page to talk about how Stephane Mallarmé and the Symbolists found the newspaper to be the modern symbol of their day, with the different stories all jostling each other for prominence on the page.

But you don’t – at least, I don’t – immediately see that when you look at the front page that McLuhan exhibits. This was presumably an extremely ordinary front page when he was exhibiting it, just as the USA Today up top might be representative today. Looked at today, though, it’s something else entirely, especially when you what newspapers look like now. You can notice this even in my thumbnails: when both papers are normalized to 200 pixels wide, you can’t read anything in the old one, besides that it says “The New York Times” as the top, whereas you can make out the headlines to four stories in the USA Today. Newspapers have changed, not just from black & white to color, but in the way the present text and images. In the old paper there are only two photos, headshots of white men in the news – one a politician who’s just given a speech, the other a doctor who’s had his license revoked. The USA Today has perhaps an analogue to that photo in Jack Abramoff’s perp walk; it also has five other photos, one of the miners’ deluded family members (along with Abramoff, the only news photos), two sports-related photos – one of which seems to be stock footage of the Rose Bowl sign, a photo advertising television coverage inside, and a photo of two students for a human interest story. This being the USA Today, there’s also a silly graph in the bottom left; the green strip across the bottom is an ad.

Photos and graphics take up more than a third of the front page of today’s paper.

What’s overwhelming to me about the old Times cover is how much text there is. This was not a newspaper that was meant to be read at a glance – as you can do with the thumbnail of the USA Today. If you look at the Times more closely it looks like everything on the front page is serious news. You could make an argument here about the decline of journalism, but I’m not that interested in that. More interesting is how visual print culture has become. Technology has enabled this – a reasonably intelligent high-schooler could, I think, create a layout like the USA Today. But having this possibility available would also seem to have had an impact on the content – and whether McLuhan would have predicted that, I can’t say.

pulitzers will accept online journalism

Online news is now fair game for all fourteen journalism categories of the Pulitzer Prize (previously only the Public Service category accepted online entries). However, online portions of prize submissions must be text-based, and the only web-exclusive content accepted will be in the breaking news reporting and breaking news photography categories.  But this presumably opens the door to some Katrina-related Pulitzers this April. I would put my bets on nola.com, the New Orleans Times-Picayune site that kept reports flying online throughout the hurricane.

But this presumably opens the door to some Katrina-related Pulitzers this April. I would put my bets on nola.com, the New Orleans Times-Picayune site that kept reports flying online throughout the hurricane.

Of course, the significance of this is mainly symbolic. When the super-prestigious Pulitzer (that’s him to the right) starts to re-align its operations, you know there are bigger plate tectonics at work. This would seem to herald an eventual embrace of blogs, most obviously in the areas of commentary, beat reporting, community service, and explanatory reporting (though investigative reporting may not be far off). The committee would do well to consider adding a “news analysis” category for all the fantastic websites, many of them blogs, that help readers make sense of the news and act as a collective watchdog for the press.

Also, while the Pulitzer changes evince a clear preference for the written word, it seems inevitable that inter-media journalism will continue to gain in both quality and legitimacy. We’ll probably look back on all the Katrina coverage as the watershed moment. Newspapers (some of them anyway) will figure out that to stay relevant, and distinctive enough not to be pulled apart by aggregators like Google or Yahoo news search, they will have to weave a richer tapestry of traditional reporting, commentary, features, and rich multimedia: a unique window to the world.

Nola.com didn’t just provide good, constant coverage, it saved lives. It was an indispensible, unique portal that could not be matched by any aggregator (though harnessing the power of aggregation is part of what made it successful). The crisis of the hurricane put in relief what could be a more everyday strategy for newspapers. The NY Times currently is experimenting with this, developing a range of multimedia features and cordoning off premium content behind its Select pay wall. While I don’t think they’ve yet figured out the right combination of premium content to attract large numbers of paying web subscribers, their efforts shouldn’t necessarily be dismissed.

Discussions on the future of the news industry usually center around business models and the problem of solvency with a web-based model. These questions are by no means trivial, but what they tend to leave out is how the evolving forms of journalism might affect what readers consider valuable. And value is, after all, what you can charge for. It’s fatalistic to assume that the web’s entropic power will just continue to wear down news institutions until they vanish. The tendency on the web toward fragmentation is indeed strong, but I wouldn’t underestimate the attraction of a quality product.

A couple of years ago, file sharing seemed to spell doom for the music industry, but today online music retailers are outselling most physical stores. Perhaps there is a way for news as well, but the news will have to change. Dan Gillmor is someone who has understood this for quite some time, and I quote from a rather prescient opinion piece he wrote back in 1997 when the Pulitzers were just beginning to wonder what to do about all this new media (this came up today on the Poynter Online-News list):

When we take journalism into the digital realm, media distinctions lose their meaning. My newspaper is creating multimedia journalism, including video reports, for our Web site. We strongly believe that the online component of our work augments what we sometimes call the “dead-tree” edition, the newspaper itself. Meanwhile, CNN is running text articles on its Web site, adding context to video reports.

So you have to ask a simple question or two: Online, what’s a newspaper? What’s a broadcaster?

Suppose CNN posts a particularly fine video report on its Web site, augmented by old-fashioned text and graphics. If the Pulitzer Prizes are o pen to online content, the CNN report should be just as valid an entry as, say, a newspaper series posted online and augmented with video.

And what about the occasionally exceptional journalism we’re seeing from Web sites (or on CD-ROMs) produced by magazines, newsletters, online-only companies or even self-appointed gadflies? Corporate propaganda obviously will fail the Pulitzer test, but is a Microsoft-sponsored expose of venality by a competitor automatically invalid when it’s posted on the Microsoft Network news site or MSNBC? Drawing these lines will take serious wisdom, unless the Pulitzer people decide simply to ignore trends and keep the prizes the way they are, in which case the awards will become quaint – or worse, irrelevant.

I’m also intrigued by another change made by the Pulitzer committee (from the A.P.):

In a separate change, the upcoming Pulitzer guidelines for the feature writing category will give ”prime consideration to quality of writing, originality and concision.” The previous guidelines gave ”prime consideration to high literary quality and originality.”

Drop the “literary” and add “concision.” A move to brevity and a more colloquial character are already greatly in evidence in the blogosphere and it’s beginning to feed back into the establishment press. Employing once again the trusty old Pulitzer as barometer, this suggests that that most basic of journalistic forms — “the story” — is changing.

the times they are a-changin’

Knight Ridder Inc., the second largest newspaper conglomerate in the U.S., is under intense pressure from its more powerful investors to start selling off papers. The New York Times reports that the company is now contemplating “strategic alternatives.” Consider the following in terms of what Bob is saying one post down about time. With the rise of the 24-hour news cycle and the internet, news is adopting a different time signature.

It is unclear who may want to buy Knight Ridder. Newspaper companies, though still immensely profitable, have a murky future that is clouded by a shrinking readership and weak advertising revenue, both of which are being leeched away by the Internet.

…In the six moths that ended in September, newspaper circulation nationally fell 2.6 percent daily and 3.1 percent on Sundays, the biggest decline in any comparable period since 1991, according to the Audit Bureau of Circulations. All in all, 45.2 million people subscribed to 1,457 reporting papers, down from a peak of 63.3 million people and 1,688 newspapers in 1984.

By comparison, 47 million people visited newspaper Web sites, about a third of United States Internet users, according to the circulation bureau.

The time it takes to read the newspaper in print — a massive quilt, chopped up and parceled (I believe Gary Frost said something about this) — you might say it leads to a different sort of understanding of the world around you. It seems to me that the newspapers that will last longest in print are the Sunday editions, aimed at a leisurely audience, taking stock of the week that has just ended and preparing for the one about to commence. On Sundays, the world spreads out before you in print, and perhaps you make a point of taking some time away from the computer (at least, this might be the case for hybrid monkeys like me who are more or less at home with both print and digital). The briskness of discourse on the web and in popular culture does not afford the time to engage with big ideas. Bob talks, not without irony, about “tithing to the church of big ideas.” Set aside the time to engage with world-changing ideas, willfully turn away from the screen.

The persistence of the Sunday print edition, if it comes to pass, might in some way reflect this kind of tithing, this intentional slowing down.

more bad news for print news

These figures (scroll down) aren’t pretty, but keep in mind that they convey more than a simple flight of readership. Part of it is a conscious decision by newspapers to cut out costly promotional efforts and to re-focus on core circulation. But the overall trend, and the fact that the core is likely to shrink as it grows older, can’t be denied.

Things could change very suddenly if investors in the big newspaper conglomerates start demanding the sale or outright dismantling of print operations. The Los Angeles Times reported yesterday of pressure building at Knight Ridder Inc., where the more powerful shareholders, dismayed with the continued tumbling of stock values, seem to be urging things toward a reckoning, some even welcoming the idea of a hostile takeover. The Times: “…if shareholders force the sale or the dismantling of Knight Ridder, few in the newspaper industry expect the revolt to stop there.”

The pre-Baby Boom generation typically subscribed to several newspapers, something that changed when the Boomers came of age. While competition with the web may be a major factor in recent upheavals, there are generational tectonics at work as well, habits formed long ago that are only now expressing themselves in the marketplace. Even if newspapers start to phase out print and focus entirely on the web, the erosion is likely to continue. It’s not just the distribution model that changes, but the whole conceptual framework.

Ray, who just joined us here at the institute, was talking today about how online social networks are totally changing the way the younger generation gets its news. It’s much more about the network of friends, the circulation of news from diverse sources through the collective filter, and not about your trusted daily paper. So the whole idea of a centralized news organization is shifting and perhaps dissolving.

From the L.A. Times:

Average weekday circulation of the nation’s 20 biggest newspapers for the six-month period ended Sept. 30 and percentage change from a year earlier:

1. USA Today, 2,296,335, down 0.59%

2. Wall Street Journal, 2,083,660, down 1.1%

3. New York Times, 1,126,190, up 0.46%

4. Los Angeles Times, 843,432, down 3.79%

5. New York Daily News, 688,584, down 3.7%

6. Washington Post, 678,779, down 4.09%

7. New York Post, 662,681, down 1.74%

8. Chicago Tribune, 586,122, down 2.47%

9. Houston Chronicle, 521,419, down 6.01%*

10. Boston Globe, 414,225, down 8.25%

11. Arizona Republic, 411,043, down 0.54%*

12. Star-Ledger of Newark, N.J., 400,092, up 0.01%

13. San Francisco Chronicle, 391,681, down 16.4%*

14. Star Tribune of Minneapolis-St. Paul, 374,528, down 0.26%

15. Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 362,426, down 8.73%

16. Philadelphia Inquirer, 357,679, down 3.16%

17. Detroit Free Press, 341,248, down 2.18%

18. Plain Dealer, Cleveland, 339,055, down 4.46%

19. Oregonian, Portland, 333,515, down 1.24%

20. San Diego Union-Tribune, 314,279, down 6.24%

a future written in electronic ink?

Discussions about the future of newspapers often allude to a moment in the Steven Spielberg film “Minority Report,” set in the year 2054, in which a commuter on the train is reading something that looks like a paper copy of USA Today, but which seems to be automatically updating and rearranging its contents like a web page. This is a comforting vision for the newspaper business: reassigning the un-bottled genie of the internet to the familiar commodity of the broadsheet. But as with most science fiction, the fallacy lies in the projection of our contemporary selves into an imagined future, when in fact people and the way they read may have very much changed by the year 2054.

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Being a newspaper is no fun these days. The demand for news is undiminished, but online readers (most of us now) feel entitled to a free supply. Print circulation numbers continue to plummet, while the cost of newsprint steadily rises — it hovers right now at about $625 per metric ton (according to The Washington Post, a national U.S. paper can go through around 200,000 tons in a year).

Staffs are being cut, hiring freezes put into effect. Some newspapers (The Guardian in Britain and soon the Wall Street Journal) are changing the look and reducing the size of their print product to lure readers and cut costs. But given the rather grim forecast, some papers are beginning to ponder how other technologies might help them survive.

Last week, David Carr wrote in the Times about “an ipod for text” as a possible savior — a popular, portable device that would reinforce the idea of the newspaper as something you have in your hand, that you take with you, thereby rationalizing a new kind of subscription delivery. This weekend, the Washington Post hinted at what that device might actually be: a flexible, paper-like screen using “e-ink” technology.

An e-ink display is essentially a laminated sheet containing a thin layer of fluid sandwiched between positive and negative electrodes. Tiny capsules of black and white pigment float in between and arrange themselves into images and text through variance in the charge (the black are negatively charged and the white positively charged). Since the display is not light-based (like the electronic screens we use today), it has an appearance closer to paper. It can be read in bright sunlight, and requires virtually no power to maintain an image.

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public online chat with Russ Wilcox, the chief exec of E Ink Corp. Wilcox predicts that large e-ink screens will be available within a year or two, opening the door for newspapers to develop an electronic product that combines web and broadsheet. Even offering the screens to subscribers for free, he calculates, would be more cost-efficient than the current paper delivery system.

Frank Ahrens, who wrote the Post piece, held a public online chat with Russ Wilcox, the chief exec of E Ink Corp. Wilcox predicts that large e-ink screens will be available within a year or two, opening the door for newspapers to develop an electronic product that combines web and broadsheet. Even offering the screens to subscribers for free, he calculates, would be more cost-efficient than the current paper delivery system.

A number of major newspaper conglomerates — including The Hearst Corporation, Gannett Co. (publisher of USA Today), TOPPAN Printing Company of Japan, and France’s Vivendi Universal Publishing — are interested enough in the potential of e-ink that they have become investors.

But maybe it won’t be the storied old broadsheet that people crave. A little over a month ago at a trade show in Berlin, Philips Polymer Vision presented a prototype of its new “Readius” — a device about the size of a mobile phone with a roll-out e-ink screen. This, too, could be available soon. Like it or not, it might make more sense to watch what’s developing with cell phones to get a hint of the future.

But even if electronic paper catches on — and it seems likely that it, or something similar, will — I wouldn’t count on it to solve the problems of the print news industry. It’s often tempting to think of new technologies that fundamentally change the way we operate as simply a matter of pouring old wine into new bottles. But electronic paper will be a technology for delivering the web, or even internet television — not individual newspapers. So then how do we preserve (or transfer) all that is good about print media, about institutions like the Times and the Post, assuming that their prospects continue to worsen? The answer to that, at least for now, is written in invisible ink.

it seems to be happening before our eyes

it looks like one hundred years from now history may record that 2005 was the year that big (news) media gave way to the individual voice. the intersection of the ny times/judy miller debacle with the increasing influence of the blogosphere has made us conscious of the major change taking place — RIGHT NOW.

congressman john conyers wrote today that “I find I learn more reading Arianna, Murray Waas and Lawrence O’Donnell than the New York Times or Washington Post.”

wow!

ok — it’s judy time at if:book; but i promise only future-of-the-book related comments

these thoughts came immediately after reading the NY Times’ sad attempt to explain how the “newspaper of record” managed to lose its integrity.

1. looks to me as if the media (ny times) has become the news and the blogging community are functioning as the real journalists. can anyone reading this blog, who has been following the judith miller situation say they didn’t go to the blogosphere today to get a decent handle on how to parse what the Times just did to “cover the Judith Miller” story.

2. i want a juan cole equivalent for the judy miller story; someone who specializes in the working of behind-the-scenes washington and who knows enough about law and history to put each day’s events in perpective. at the very least i want someone to present me with the ten most useful accounts on the web so that i can triangulate the problem.

3. perhaps it would be a good thought experiment to try to come up with interesting ideas of how to organize references on the web to the judith miller situation. how would you present an overview of the references?

an ipod for text

When I ride the subway, I see a mix of paper and plastic. Invariably several passengers are lost in their ipods (there must be a higher ipod-per-square-meter concentration in New York than anywhere else). One or two are playing a video game of some kind. Many just sit quietly with their thoughts. A few are conversing. More than a few are reading. The subway is enormously literate. A book, a magazine, The Times, The Post, The Daily News, AM New York, Metro, or just the ads that blanket the car interior. I may spend a lot of time online at home or at work, but on the subway, out in the city, paper is going strong.

Before long, they’ll be watching television on the subway too, seeing as the latest ipod now plays video. But rewind to Monday, when David Carr wrote in the NY Times about another kind of ipod — one that would totally change the way people read newspapers. He suggests that to bounce back from these troubled times (sagging print circulation, no reliable business model for their websites), newspapers need a new gadget to appear on the market: a light-weight, highly portable device, easy on the eyes, easy on the batteries, that uploads articles from the web so you can read them anywhere. An ipod for text.

This raises an important question: is it all just a matter of the reading device? Once there are sufficient advances in display technology, and a hot new gadget to incorporate them, will we see a rapid, decisive shift away from paper toward portable electronic text, just as we have witnessed a widespread migration to digital music and digital photography? Carr points to a recent study that found that in every age bracket below 65, a majority of reading is already now done online. This is mostly desktop reading, stationary reading. But if the greater part of the population is already sold on web-based reading, perhaps it’s not too techno-deterministic to suppose that an ipod-like device would in fact bring sweeping change for portable reading, at least periodicals.

But the thing is, online reading is quite different from print reading. There’s a lot of hopping around, a lot of digression. Any new hardware that would seek to tempt people to convert from paper would have to be able to surf the web. With mobile web, and wireless networks spreading, people would expect nothing less (even the new Sony PSP portable gaming device has a web browser). But is there a good way to read online text when you’re offline? Should we be concerned with this? Until wi-fi is ubiquitous and we’re online all the time (a frightening thought), the answer is yes.

We’re talking about a device that you plug into your computer that automatically pulls articles from pre-selected sources, presumably via RSS feeds. This is more or less how podcasting works. But for this to have an appeal with text, it will have to go further. What if in addition to uploading new articles in your feed list, it also pulled every document that those articles linked to, so you could click through to referenced sites just as you would if you were online?

It would be a bounded hypertext system. You could do all the hopping around you like within the cosmos of that day’s feeds, and not beyond — you would have the feeling of the network without actually being hooked in. Text does not take up a lot of hard drive space, and with the way flash memory is advancing, building a device with this capacity would not be hard to achieve. Of course, uploading link upon link could lead down an infinite paper trail. So a limit could be imposed, say, a 15-step cap — a limit that few are likely to brush up against.

So where does the money come in? If you want an ipod for text, you’re going to need an itunes for text. The “portable, bounded hypertext RSS reader” (they’d have to come up with a catchier name –the tpod, or some such techno-cuteness) would be keyed in to a subscription service. It would not be publication-specific, because then you’d have to tediously sign up with dozens of sites, and no reasonable person would do this.

So newspapers, magazines, blogs, whoever, will sign licensing agreements with the tpod folks and get their corresponding slice of the profits based on the success of their feeds. There’s a site called KeepMedia that is experimenting with such a model on the web, though not with any specific device in mind (and it only includes mainstream media, no blogs). That would be the next step. Premium papers like the Times or The Washington Post might become the HBOs and Showtimes of this text-ripping scheme — pay a little extra and you get the entire electronic edition uploaded daily to your tpod.

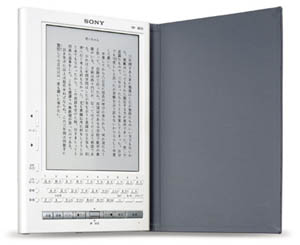

As for the device, well, the Sony Librie has had reasonable success in Japan and will soon be released in the States. The Librie is incredibly light and uses an “e-ink” display that is reflective like paper (i.e. it can be read in bright sunlight), and can run through 10,000 page views on four triple-A batteries.

As for the device, well, the Sony Librie has had reasonable success in Japan and will soon be released in the States. The Librie is incredibly light and uses an “e-ink” display that is reflective like paper (i.e. it can be read in bright sunlight), and can run through 10,000 page views on four triple-A batteries.

The disadvantages: it’s only black-and-white and has no internet connectivity. It also doesn’t seem to be geared for pulling syndicated text. Bob brought one back from Japan. It’s nice and light, and the e-ink screen is surprisingly sharp. But all in all, it’s not quite there yet.

There’s always the do-it-yourself approach. The Voyager Company in Japan has developed a program called T-Time (the image at the top is from their site) that helps you drag and drop text from the web into an elegant ebook format configureable for a wide range of mobile devices: phones, PDAs, ipods, handheld video games, camcorders, you name it. This demo (in Japanese, but you’ll get the idea) demonstrates how it works.

Presumably, you would also read novels on your text pod. I personally would be loathe to give up paper here, unless it was a novel that had to be read electronically because it was multimedia, or networked, or something like that. But for syndicated text — periodicals, serials, essays — I can definitely see the appeal of this theoretical device. I think it’s something people would use.