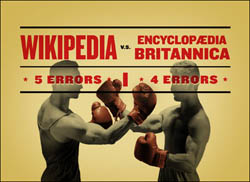

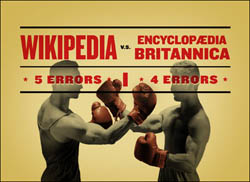

In a nice comment in yesterday’s Times, “The Nitpicking of the Masses vs. the Authority of the Experts,” George Johnson revisits last month’s Seigenthaler smear episode and Nature magazine Wikipedia-Britannica comparison, and decides to place his long term bets on the open-source encyclopedia:

In a nice comment in yesterday’s Times, “The Nitpicking of the Masses vs. the Authority of the Experts,” George Johnson revisits last month’s Seigenthaler smear episode and Nature magazine Wikipedia-Britannica comparison, and decides to place his long term bets on the open-source encyclopedia:

It seems natural that over time, thousands, then millions of inexpert Wikipedians – even with an occasional saboteur in their midst – can produce a better product than a far smaller number of isolated experts ever could.

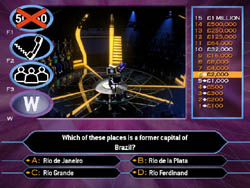

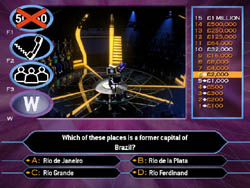

Reading it, a strange analogy popped into my mind: “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.” Yes, the game show. What does it have to do with encyclopedias, the internet and the re-mapping of intellectual authority? I’ll try to explain. “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” is a simple quiz show, very straightforward, like “Jeopardy” or “The $64,000 Question.” A single contestant answers a series of multiple choice questions, and with each question the money stakes rise toward a million-dollar jackpot. The higher the stakes the harder the questions (and some seriously overdone lighting and music is added for maximum stress). There is a recurring moment in the game when the contestant’s knowledge fails and they have the option of using one of three “lifelines” that have been alloted to them for the show.

The first lifeline (and these can be used in any order) is the 50:50, which simply reduces the number of possible answers from four to two, thereby doubling your chances of selecting the correct one — a simple jiggering of probablities.  The other two are more interesting. The second lifeline is a telephone call to a friend or relative at home who is given 30 seconds to come up with the answer to the stumper question. This is a more interesting kind of a probability, since it involves a personal relationship. It deals with who you trust, who you feel you can rely on. Last, and my favorite, is the “ask the audience” lifeline, in which the crowd in the studio is surveyed and hopefully musters a clear majority behind one of the four answers. Here, the probability issue gets even more intriguing. Your potential fortune is riding on the knowledge of a room full of strangers.

The other two are more interesting. The second lifeline is a telephone call to a friend or relative at home who is given 30 seconds to come up with the answer to the stumper question. This is a more interesting kind of a probability, since it involves a personal relationship. It deals with who you trust, who you feel you can rely on. Last, and my favorite, is the “ask the audience” lifeline, in which the crowd in the studio is surveyed and hopefully musters a clear majority behind one of the four answers. Here, the probability issue gets even more intriguing. Your potential fortune is riding on the knowledge of a room full of strangers.

In most respects, “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire” is just another riff on the classic quiz show genre, but the lifeline option pegs it in time, providing a clue about its place in cultural history. The perceptive game show anthropologist would surely recognize that the lifeline is all about the network. It’s what gives “Millionaire” away as a show from around the time of the tech bubble in the late 90s — manifestly a network-era program. Had it been produced in the 50s, the lifeline option would have been more along the lines of “ask the professor!” Lights rise on a glass booth containing a mustached man in a tweed jacket sucking on a pipe. Our cliché of authority. But “Millionaire” turns not to the tweedy professor in the glass booth (substitute ivory tower) but rather to the swarming mound of ants in the crowd.

And that’s precisely what we do when we consult Wikipedia. It isn’t an authoritative source in the professor-in-the-booth sense. It’s more lifeline number 3 — hive mind, emergent intelligence, smart mobs, there is no shortage of colorful buzzwords to describe it. We’ve always had lifeline number 2. It’s who you know. The friend or relative on the other end of the phone line. Or think of the whispered exchange between students in the college library reading room, or late-night study in the dorm. Suddenly you need a quick answer, an informal gloss on a subject. You turn to your friend across the table, or sprawled on the couch eating Twizzlers: When was the Glorious Revolution again? Remind me, what’s the Uncertainty Principle?

With Wikipedia, this friend factor is multiplied by an order of millions — the live studio audience of the web. This is the lifeline number 3, or network, model of knowledge. Individual transactions may be less authoritative, pound for pound, paragraph for paragraph, than individual transactions with the professors. But as an overall system to get you through a bit of reading, iron out a wrinkle in a conversation, or patch over a minor factual uncertainty, it works quite well. And being free and informal it’s what we’re more inclined to turn to first, much more about the process of inquiry than the polished result. As Danah Boyd puts it in an excellently measured defense of Wikipedia, it “should be the first source of information, not the last. It should be a site for information exploration, not the definitive source of facts.” Wikipedia advocates and critics alike ought to acknowledge this distinction.

So, having acknowledged it, can we then broker a truce between Wikipedia and Britannica? Can we just relax and have the best of both worlds? I’d like that, but in the long run it seems that only one can win, and if I were a betting man, I’d have to bet with Johnson. Britannica is bound for obsolescence. A couple of generations hence (or less), who will want it? How will it keep up with this larger, far more dynamic competitor that is already of roughly equal in quality in certain crucial areas?

So, having acknowledged it, can we then broker a truce between Wikipedia and Britannica? Can we just relax and have the best of both worlds? I’d like that, but in the long run it seems that only one can win, and if I were a betting man, I’d have to bet with Johnson. Britannica is bound for obsolescence. A couple of generations hence (or less), who will want it? How will it keep up with this larger, far more dynamic competitor that is already of roughly equal in quality in certain crucial areas?

Just as the printing press eventually drove the monastic scriptoria out of business, Wikipedia’s free market of knowledge, with all its abuses and irregularities, its palaces and slums, will outperform Britannica’s centralized command economy, with its neat, cookie-cutter housing slabs, its fair, dependable, but ultimately less dynamic, system. But, to stretch the economic metaphor just a little further before it breaks, it’s doubtful that the free market model will remain unregulated for long. At present, the world is beginning to take notice of Wikipedia. A growing number are championing it, but for most, it is more a grudging acknowledgment, a recognition that, for better of for worse, what’s going on with Wikipedia is significant and shouldn’t be ignored.

Eventually we’ll pass from the current phase into widespread adoption. We’ll realize that Wikipedia, being an open-source work, can be repackaged in any conceivable way, for profit even, with no legal strings attached (it already has been on sites like about.com and thousands — probably millions — of spam and link farms). As Lisa intimated in a recent post, Wikipedia will eventually come in many flavors. There will be commercial editions, vetted academic editions, handicap-accessible editions. Darwinist editions, creationist editions. Google, Yahoo and Amazon editions. Or, in the ultimate irony, Britannica editions! (If you can’t beat ’em…)

All the while, the original Wikipedia site will carry on as the sprawling community garden that it is. The place where a dedicated minority take up their clippers and spades and tend the plots. Where material is cultivated for packaging. Right now Wikipedia serves best as an informal lifeline, but soon enough, people will begin to demand something more “authoritative,” and so more will join in the effort to improve it. Some will even make fortunes repackaging it in clever ways for which people or institutions are willing to pay. In time, we’ll likely all come to view Wikipedia, or its various spin-offs, as a resource every bit as authoritative as Britannica. But when this happens, it will no longer be Wikipedia.

Authority, after all, is a double-edged sword, essential in the pursuit of truth, but dangerous when it demands that we stop asking questions. What I find so thrilling about the Wikipedia enterprise is that it is so process-oriented, that its work is never done. The minute you stop questioning it, stop striving to improve it, it becomes a museum piece that tells the dangerous lie of authority. Even those of use who do not take part in the editorial gardening, who rely on it solely as lifeline number 3, we feel the crowd rise up to answer our query, we take the knowledge it gives us, but not (unless we are lazy) without a grain of salt. The work is never done. Crowds can be wrong. But we were not asking for all doubts to be resolved, we wanted simply to keep moving, to keep working. Sometimes authority is just a matter of packaging, and the packaging bonanza will soon commence. But I hope we don’t lose the original Wikipedia — the rowdy community garden, lifeline number 3. A place that keeps you on your toes — that resists tidy packages.

The artist Nam June Paik passed away on Sunday. Paik’s justifiably known as the first video artist, but thinking of him as “the guy who did things with TVs” does him the disservice of neglecting how visionary his thought was – and that goes beyond his coining of the term “electronic superhighway” (in a 1978 report for the Ford Foundation) to describe the increasingly ubiquitous network that surrounds us. Consider as well his vision of Utopian Laser Television, a manifesto from 1962 that argued for

The artist Nam June Paik passed away on Sunday. Paik’s justifiably known as the first video artist, but thinking of him as “the guy who did things with TVs” does him the disservice of neglecting how visionary his thought was – and that goes beyond his coining of the term “electronic superhighway” (in a 1978 report for the Ford Foundation) to describe the increasingly ubiquitous network that surrounds us. Consider as well his vision of Utopian Laser Television, a manifesto from 1962 that argued for