The first two major ARGs to play out, The Beast and ilovebees, surprised their creators: the collective intelligence of thousands of players was taking down in hours puzzles that the puppetmasters had expected the community to wrestle with for days. And in order for the game not to go stale, new challenges – sometimes created on the fly – had to keep coming. If the content fizzled out, or the puzzles were too easy, the players would become restless and lose interest.

I was reminded of this by the recent discussion on this blog about hypertext. ‘Boring’ is such a loaded word; and yet so much of the Web feels, to me, deeply boring. Even the interesting stuff. Internet addiction is all about clicking across link after link, page after page of content, unable to tear oneself away but still strangely bored. Faced with infinite places to go, all content becomes undifferentiated; lacking in narrative; boring. Much like the paralysis consumers face when confronted with 15 near-identical types of pesto, choice of content made as easy as a click here or there reduces it all to a blur.

I found myself pondering easy choice, supermarket paralysis and internet addiction in the context of the exciting promise and strange underwhelmingness of much hyperfiction. Then, yesterday, interactive game creator and SixToStart ARG writer James Wallis said something that flipped the light on. “Writing for interactive is different to print writing,” he said. But this isn’t in the way someone habituated to storytelling on paper might expect. For such, ‘interactive’ might suggest an exciting opportunity to cast off the formal shackles of one-page-after-the-next. (Certainly, when I first came across HTTP, that’s what it seemed to promise me). “When you think of interactive, you think of the Garden of Forking Paths, non-linear narrative and so on. But if you want people to stay interested, that doesn’t work at all.”

Instead, he says, writing for interactive takes a more or less linear narrative, and makes the reader/user/player work it. In an ARG, a crucial piece of information might be hidden behind a login that needs to be hacked; the story’s progression might depend on a puzzle being solved to reveal a code. The payoff of interactivity, the thing that gives the story a hook that it couldn’t get otherwise, is less about ‘choice’ or a pleasure of diverging from linear narrative, than a sense of active contribution to the progression of that narrative. Of course, because an ARG plays out in real time, players may solve things ‘too’ quickly or take the story in a new direction – then, to avoid shattering the ‘This Is Not A Game’ illusion the puppetmasters must create new content to reflect that divergence.

Earlier, in a comment on the hypertext discussion, I found myself pondering emotional involvement – as measured by whether a story can move you to tears – in the context of interactive narrative. Games that eschew development of ‘characters’ in favor of making you, the central protagonist, the ‘character’ that develops. Tearjerking moments in 1983 text-based adventure games. How does a character or situation creep up on us so that we care enough to be sad when they’re gone?

Perhaps it’s easier to let this happen when you’re being swept along by a movie, or barely noticing as you turn page after page. I can’t prove this, but it feels as though having to make empty, consequence-free choices about where a narrative goes next pulls me back from imaginative involvement to a more meta-level, strategic, structural kind of thinking, that’s inimical to emotional absorption. It’s a bit like something pulling me back from an exciting moment in my book and inviting me to contemplate the paper. Forcing me to choose between narrative possibilities, when that choice has (as in the supermarket, faced with the rows of pesto choices) no consequences, and implying too – as the supermarket does – that choice were in itself a positive addition to my experience, in fact undermines my ability to relax into that experience. Compare that to a hidden group of puppetmasters evolving a narrative on the fly to fit around an amorphous, self-organizing group of players, going to extraordinary lengths to avoid rupturing the story’s consistency, and you can see that here are radically different kinds of ‘interactive’.

Making you work for the next chunk of story, or making you the central protagonist. If these are two narrative tools that demonstrably help make stories work in a digital space, are there more? And are they perceived as markers for quality interactive fiction? Or are game-like narratives still considered somehow a ‘lower’ art form, nerdy and plebeian, unsuitable for ‘serious’ writing or consideration as powerful narrative? I would welcome any evidence to the contrary.

Category Archives: narrative

hypertextopia

We were recently alerted, via Grand Text Auto, to a new hypertext fiction environment on the Web called Hypertextopia:

Hypertextopia is a space where you can read and write stories for the internet. On the surface, it looks like a mind-map, but it embeds a word-processor, and allows you to publish your stories like a blog.

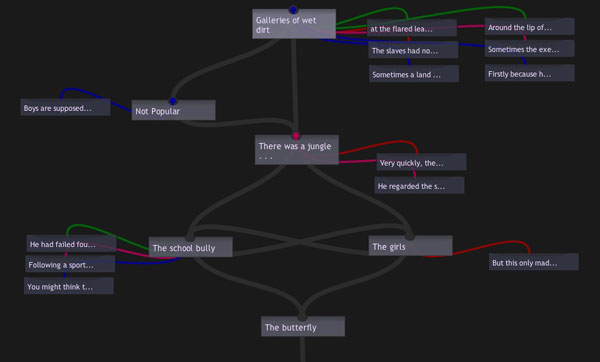

The site is gorgeously done, applying a fresh coat of Web 2.0 paint to the creaky concepts of classical hypertext. I find myself strangely conflicted, though, as I browse through it. Design-wise, it is a triumph, and really gets my wheels spinning w/r/t the possibilities of online writing systems. The authoring tools they’ve developed are simple and elegant, allowing you to write “axial hypertexts”: narratives with a clear beginning and end but with multiple pathways and digressions in between. You read them as a series of textual screens, which can include beautiful fold-out boxes for annotations and illustrations, and various color-coded links (the colors denote different types of internal links, which the author describes). You also have the option of viewing stories as nodal maps, which show the story’s underlying structure. This is part of the map of “The Butterfly Boy” by William Vollmann (by all indications, the William Vollmann):

Lovely as it all is though, it doesn’t convince me that hypertext is any more viable a literary form now, on the Web, than it was back in the heyday of Eastgate and Storyspace. Outside its inner circle of devotees, hypertext has always been more interesting in concept than in practice. A necessary thought experiment on narrative’s deconstruction in a post-book future, but not the sort of thing you’d want to read for pleasure.

It’s always felt to me like a too-literal reenactment of Jorge Luis Borges’ explosion of narrative in The Garden of Forking Paths. In the story, the central character, a Chinese double agent in WWI being pursued by a British assassin who has learned of his treachery, recalls a lost, unfinished novel written by a distant ancestor. It is an infinte story that encompasses every possible event and outcome for its characters: a labyrinth, not in space but in time. Borges meant the novel not as a prescription for a new literary form but as a metaphor of parallel worlds, yet many have cited this story as among the conceptual forebears of hypertext fiction, and Borges is much revered generally among technophiles for writing fables that eerily prefigure the digital age.

I’ve always found it odd how people (techies especially) seem to get romantic (perhaps fetishistic is the better word) about Borges. Prophetic he no doubt was, but his tidings are dark ones. Tales like “Forking Paths,” Funes the Memorious and The Library of Babel are ideas taken to a frightening extreme, certainly not things we would wish to come true. There are days when the Internet does indeed feel a bit like the Library of Babel, a place where an infinity of information has led to the death of meaning. But those are the days I wish we could put the net back in the box and forget it ever happened. I get a bit of that feeling with literary hypertext -? insofar as it reifies the theoretical notion of the death of the author, it is not necessarily doing the reader any favors.

Hypertext’s main offense is that it is boring, in the same way that Choose Your Own Adventure stories are fundamentally boring. I know that I’m meant to feel liberated by my increased agency as reader, but instead I feel burdened. What are offered as choices -? possible pathways though the maze -? soon start to weigh like chores. It feels like a gimmick, a cheap trick, like it doesn’t really matter which way you go (that the prose tends to be poor doesn’t help). There’s a reason hypertext never found an audience.

I can, however, see the appeal of hypertext fictions as puzzles or games. In fact, this may be their true significance in the evolution of storytelling (and perhaps why I don’t get them, because I’m not a gamer). Thought of this way, it’s more about the experience of navigating a narrative landscape than the narrative itself. The story is a sort of alibi, a pretext, for engaging with a particular kind of form, a form which bears far more resemblance to a game than to any kind of prose fiction predecessor. That, at any rate, is how I’ve chosen to situate hypertext. To me, it’s a napkin sketch of a genuinely new form -? video games -? that has little directly to do with writing or reading in the traditional sense. Hypertext was not the true garden of forking paths (which we would never truly want anyway), but a small box of finite options. To sift through them dutifully was about as fun as the lab rat’s journey through the maze. You need a bigger algorithmic engine and the sensory fascinations of graphics (and probably a larger pool of authors and co-creators too) to generate a topography vast enough to hide, at least for a while, its finiteness -? long enough to feel mysterious. That’s what games do, and do well.

I’m sure this isn’t an original observation, but it’s baggage I felt like unloading since classical hypertext is a topic we’ve largely skirted around here at the Institute. Grumbling aside though, Hypertextopia offers much to ponder. Recontextualizing a pre-Web form in the Web is a worthwhile experiment and is bound to shed some light. I’m thinking about how we might play around in it…

ecclesiastical proust archive: starting a community

(Jeff Drouin is in the English Ph.D. Program at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York)

About three weeks ago I had lunch with Ben, Eddie, Dan, and Jesse to talk about starting a community with one of my projects, the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive. I heard of the Institute for the Future of the Book some time ago in a seminar meeting (I think) and began reading the blog regularly last Summer, when I noticed the archive was mentioned in a comment on Sarah Northmore’s post regarding Hurricane Katrina and print publishing infrastructure. The Institute is on the forefront of textual theory and criticism (among many other things), and if:book is a great model for the kind of discourse I want to happen at the Proust archive. When I finally started thinking about how to make my project collaborative I decided to contact the Institute, since we’re all in Brooklyn, to see if we could meet. I had an absolute blast and left their place swimming in ideas!

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together.

While my main interest was in starting a community, I had other ideas — about making the archive more editable by readers — that I thought would form a separate discussion. But once we started talking I was surprised by how intimately the two were bound together.

For those who might not know, The Ecclesiastical Proust Archive is an online tool for the analysis and discussion of à la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time). It’s a searchable database pairing all 336 church-related passages in the (translated) novel with images depicting the original churches or related scenes. The search results also provide paratextual information about the pagination (it’s tied to a specific print edition), the story context (since the passages are violently decontextualized), and a set of associations (concepts, themes, important details, like tags in a blog) for each passage. My purpose in making it was to perform a meditation on the church motif in the Recherche as well as a study on the nature of narrative.

I think the archive could be a fertile space for collaborative discourse on Proust, narratology, technology, the future of the humanities, and other topics related to its mission. A brief example of that kind of discussion can be seen in this forum exchange on the classification of associations. Also, the church motif — which some might think too narrow — actually forms the central metaphor for the construction of the Recherche itself and has an almost universal valence within it. (More on that topic in this recent post on the archive blog).

Following the if:book model, the archive could also be a spawning pool for other scholars’ projects, where they can present and hone ideas in a concentrated, collaborative environment. Sort of like what the Institute did with Mitchell Stephens’ Without Gods and Holy of Holies, a move away from the ‘lone scholar in the archive’ model that still persists in academic humanities today.

One of the recurring points in our conversation at the Institute was that the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive, as currently constructed around the church motif, is “my reading” of Proust. It might be difficult to get others on board if their readings — on gender, phenomenology, synaesthesia, or whatever else — would have little impact on the archive itself (as opposed to the discussion spaces). This complex topic and its practical ramifications were treated more fully in this recent post on the archive blog.

I’m really struck by the notion of a “reading” as not just a private experience or a public writing about a text, but also the building of a dynamic thing. This is certainly an advantage offered by social software and networked media, and I think the humanities should be exploring this kind of research practice in earnest. Most digital archives in my field provide material but go no further. That’s a good thing, of course, because many of them are immensely useful and important, such as the Kolb-Proust Archive for Research at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Some archives — such as the NINES project — also allow readers to upload and tag content (subject to peer review). The Ecclesiastical Proust Archive differs from these in that it applies the archival model to perform criticism on a particular literary text, to document a single category of lexia for the experience and articulation of textuality.

If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.

If the Ecclesiastical Proust Archive widens to enable readers to add passages according to their own readings (let’s pretend for the moment that copyright infringement doesn’t exist), to tag passages, add images, add video or music, and so on, it would eventually become a sprawling, unwieldy, and probably unbalanced mess. That is the very nature of an Archive. Fine. But then the original purpose of the project — doing focused literary criticism and a study of narrative — might be lost.

If the archive continues to be built along the church motif, there might be enough work to interest collaborators. The enhancements I currently envision include a French version of the search engine, the translation of some of the site into French, rewriting the search engine in PHP/MySQL, creating a folksonomic functionality for passages and images, and creating commentary space within the search results (and making that searchable). That’s some heavy work, and a grant would probably go a long way toward attracting collaborators.

So my sense is that the Proust archive could become one of two things, or two separate things. It could continue along its current ecclesiastical path as a focused and led project with more-or-less particular roles, which might be sufficient to allow collaborators a sense of ownership. Or it could become more encyclopedic (dare I say catholic?) like a wiki. Either way, the organizational and logistical practices would need to be carefully planned. Both ways offer different levels of open-endedness. And both ways dovetail with the very interesting discussion that has been happening around Ben’s recent post on the million penguins collaborative wiki-novel.

Right now I’m trying to get feedback on the archive in order to develop the best plan possible. I’ll be demonstrating it and raising similar questions at the Society for Textual Scholarship conference at NYU in mid-March. So please feel free to mention the archive to anyone who might be interested and encourage them to contact me at jdrouin@gc.cuny.edu. And please feel free to offer thoughts, comments, questions, criticism, etc. The discussion forum and blog are there to document the archive’s development as well.

Thanks for reading this very long post. It’s difficult to do anything small-scale with Proust!

remix: the movie

Wired magazine reports that Michela Ledwidge is advancing the future of filmmaking, by taking cues from game moding. In early 2006, she will post all the raw material for her 10 minute sci-fi short film, Sanctuary, to the website:www.modfilms.com . People will be able to edit their own versions of the film. Sanctuary continues the open source trend also fostered by recording artists such as Jay Z who released vocal files of his Black album to encourage DJs to create their own mixes. Some die-hard Jay Z fans even posted everything you need in a similar fashion to Ledwidge.

Wired magazine reports that Michela Ledwidge is advancing the future of filmmaking, by taking cues from game moding. In early 2006, she will post all the raw material for her 10 minute sci-fi short film, Sanctuary, to the website:www.modfilms.com . People will be able to edit their own versions of the film. Sanctuary continues the open source trend also fostered by recording artists such as Jay Z who released vocal files of his Black album to encourage DJs to create their own mixes. Some die-hard Jay Z fans even posted everything you need in a similar fashion to Ledwidge.

I hope that many people submit films. I am very interested to see what the results will be on the aggregate level. While many people will undoubtedly create mashup versions with external content, I am especially curious to see the results from people who do not add much additional material. How many interesting stories can be told using these basic parts? Is there a “correct” shot selection or a traditional (i.e. “I learned to edit in film school”) edit? How wedded are we to traditional film narrative conventions which dictate what is “good” and “bad”? Will only a few compelling narratives arise or will many?

trapped in the closet & the form of the blook

Most of the people reading this blog probably don’t give R. Kelly – the R&B singer known for his buttery voice and slippery morals – the attention that I do, which is completely understandable. But unfortunate, because he’s very much worth keeping an eye on. For the past six months, he’s been engaged in the most formally interesting experiment in pop music in a while. I’m referring, of course, to “Trapped in the Closet”. Bear with me a bit: while it might seem like I’m off on a frolic of my own, this will get around to having something to do with the future of the book.

Most of the people reading this blog probably don’t give R. Kelly – the R&B singer known for his buttery voice and slippery morals – the attention that I do, which is completely understandable. But unfortunate, because he’s very much worth keeping an eye on. For the past six months, he’s been engaged in the most formally interesting experiment in pop music in a while. I’m referring, of course, to “Trapped in the Closet”. Bear with me a bit: while it might seem like I’m off on a frolic of my own, this will get around to having something to do with the future of the book.

“Trapped in the Closet” is, in brief, Kelly’s experiment in making a serialized pop song. The first installment of it (“Chapter 1”) arrived on a CD single last May, squeezed between “Set in the Kitchen” (a song about sex in the kitchen) and “Sex in the Kitchen (remix)” (another song about sex in the kitchen). It’s a three-and-a-half minute long song without a chorus in which Kelly lays out a plot involving multiple adulteries, a closet, and a cell phone that goes off at an inopportune moment. It ends on a cliffhanger – the narrator, hiding in the titular closet, draws his gun as the husband he’s cuckolded is about to open the door. Kelly followed this up by releasing four subsequent chapters to the radio – followed shortly by music videos – which, rather than tying up loose ends, drew out the plot wider and wider, piling adultery upon adultery, bringing a gay pastor, a police officer, and leg cramps into the story. All the chapters have the same backing music and run to the same length. And despite revelation after revelation, they all end on a cliffhanger of some sort.

For the next seven chapters, Kelly moved directly to video: he’s just released a DVD video of the first twelve chapters, where he and others act out the drama he’s narrating for thirty-nine minutes. New characters are introduced and the plot becomes steadily more labyrinthine (a midget and an allergy to cherries figure prominently) and fails to resolve much of anything. Kelly’s said to be busy thinking up a dozen more installments to the story. Through it all, the music remains the same; each episode is still three minute pop song, which do get played on the radio as such. Wikipedia does have a surprisingly good summary of the twists and turns of Kelly’s saga, though it is written in an unfortunate wink-wink-nudge-nudge style. There’s a video of the first chapter is available here; the Web being the Web, there’s a lot of so-so derivative work here, and even machinima versions of the videos here.

For the next seven chapters, Kelly moved directly to video: he’s just released a DVD video of the first twelve chapters, where he and others act out the drama he’s narrating for thirty-nine minutes. New characters are introduced and the plot becomes steadily more labyrinthine (a midget and an allergy to cherries figure prominently) and fails to resolve much of anything. Kelly’s said to be busy thinking up a dozen more installments to the story. Through it all, the music remains the same; each episode is still three minute pop song, which do get played on the radio as such. Wikipedia does have a surprisingly good summary of the twists and turns of Kelly’s saga, though it is written in an unfortunate wink-wink-nudge-nudge style. There’s a video of the first chapter is available here; the Web being the Web, there’s a lot of so-so derivative work here, and even machinima versions of the videos here.

What’s interesting about this to me? It’s partially interesting for the unbridled creativity of the endeavor: to all appearances, R. Kelly would seem to be making up the story as he goes along, happily jumping between media. But I find the most interesting aspect of this to be that R. Kelly is trying to construct a large story modularly. Each of the chapters of his story ostensibly should be able to have a life of its own as a pop song. This doesn’t quite work because his plot has become fiendishly complicated, and none save the moved devoted can make out exactly what the relationship of Rufus to Bridget might be. Presumably this is why the latest chapters were released straight to DVD, where they play sequentially. But formally each of the chapters remains identical: they all have the same backing music, start with a revelation resolving the previous cliffhanger, and end by setting up a new cliffhanger. These constraints limit what Kelly can do with the song: accordingly, his plots must become progressively more ridiculous to keep the story interesting for his listeners or viewers.

There’s an obvious analogy to the serialized novel, a recurring trope around here – we could once again trot out Charles Dickens (to whom Kelly might have been obliquely referring when he explained that ” ‘Trapped in the Closet’ was designed to go around the world sort of like the Ghost of Christmas Past – house to house, this situation to that situation, sometimes exposing people in their regular lives”). But closer at hand, there’s clearly a relevant comparison to be made to how entries function within a blog here. Just as “Trapped in the Closet” is composed of modular “chapters”, blogs are composed of entries, which are intended to stand by themselves. Kelly’s ongoing opera isn’t quite a blog, but it’s rather similar in structure.

What does it functionally mean to have a serialized narrative? One thing that shouldn’t be forgotten when scrutinizing new media forms is that form inevitably inflicts itself on content. Another: the example par excellence of the serialized narrative is the soap opera, unglamorous as that might be. Because R. Kelly has to end each chapter on a cliffhanger, his plot must become even more convoluted with every chapter. Watching the thirty-nine minutes of Trapped in the Closet Chapters 1–12 is exhausting because of this: a three minute bon bon of plot becomes cloying sweet over time. At thirty-nine minutes, Kelly’s DVD should feel like a movie. It doesn’t: its repetitiveness makes it feels like something else entirely, something that we haven’t quite seen before. Does it work? It’s hard to say.

There’s no lack of connection between the serialized narrative and the new media forms we survey here (note, for example Lisa’s post from today). I’m most interested in the formal problem that arises from the publishing industry’s latest bad idea, making books out of blogs. This does seem appealingly simple: people are writing online, if they’re good and they’ve written enough, you can slap a cover on it and call it a book. It turns out, however, that a book is more than the sum of its parts. I’m willing to give R. Kelly the benefit of the doubt with his strange DVD because it doesn’t quite feel like anything else. The problems with blogs presented as books, however, is that we expect them to behave like a book, which they don’t.

An example at hand: a friend gave my girlfriend a copy of Julie & Julia, the book that was made from Julie Powell’s blog, in which she reports on her attempts to cook all of the recipes in Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. My girlfriend, a self-identified cookbook snob & long-time devotée of Julia Child, was predictably horrified, and has spent the past week complaining about how dreadful this book is. Part of her anger is an issue of substance: she believes that Julia Child should not be dealt with so flippantly. But part of what makes her angry about the book is how the book is written. It’s not quite episodic – the editor wasn’t quite so sloppy as string together a series of blog posts and call it a book – but it does inherit much of its character from its episodic origin, which is what brings me back around to R. Kelly.

An example at hand: a friend gave my girlfriend a copy of Julie & Julia, the book that was made from Julie Powell’s blog, in which she reports on her attempts to cook all of the recipes in Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. My girlfriend, a self-identified cookbook snob & long-time devotée of Julia Child, was predictably horrified, and has spent the past week complaining about how dreadful this book is. Part of her anger is an issue of substance: she believes that Julia Child should not be dealt with so flippantly. But part of what makes her angry about the book is how the book is written. It’s not quite episodic – the editor wasn’t quite so sloppy as string together a series of blog posts and call it a book – but it does inherit much of its character from its episodic origin, which is what brings me back around to R. Kelly.

What makes a blog readable isn’t the same thing that makes a book readable. The two forms have different concerns: on a blog, an enormous part of the task of the writer is to make sure that what’s written about are interesting enough that readers keep coming back. A reader might start reading a blog at any point, so this is an ongoing concern. (Thus R. Kelly’s cliffhangers.) This isn’t nearly as necessary with a physical book: readers still need to be hooked by the concept of the book, but generally you don’t need to keep hooking them.

It might be best explained by looking at the difference between Mastering the Art of French Cooking & Powell’s book. The former was conceived as a unified whole: it’s a single big idea, elucidated in steps, from the simple to the complicated. Later parts of that book are built upon the former: they don’t work well by themselves unless you’ve already absorbed the earlier information. Julie & Julia is constructed as a series of snapshots from the life of the author, each of which seeks to be individually interesting in and of itself. How does this play out in the pages of the book? An easy example: Powell’s sex life keeps popping up in a rather gratuitous fashion. The subject isn’t without relevance in a culinary work (M.F.K. Fisher could pull this off this sort of thing astonishingly well, for example); rather, it’s the way in which it’s constantly presented in passing. This makes perfect sense for a blog: a dash of sex spices up a blog entry nicely, and will keep the readers coming back for more. A blog is explicitly built on a relationship between the reader and the writer: the writer can respond to the readers. This doesn’t work so well in a published book: this sort of interjection, rather than serving to keep the reader hooked, feels more like a constant distraction in a book not explicitly about food & sex. The reader’s already bought the book. They don’t need to be hooked again.

It might be best explained by looking at the difference between Mastering the Art of French Cooking & Powell’s book. The former was conceived as a unified whole: it’s a single big idea, elucidated in steps, from the simple to the complicated. Later parts of that book are built upon the former: they don’t work well by themselves unless you’ve already absorbed the earlier information. Julie & Julia is constructed as a series of snapshots from the life of the author, each of which seeks to be individually interesting in and of itself. How does this play out in the pages of the book? An easy example: Powell’s sex life keeps popping up in a rather gratuitous fashion. The subject isn’t without relevance in a culinary work (M.F.K. Fisher could pull this off this sort of thing astonishingly well, for example); rather, it’s the way in which it’s constantly presented in passing. This makes perfect sense for a blog: a dash of sex spices up a blog entry nicely, and will keep the readers coming back for more. A blog is explicitly built on a relationship between the reader and the writer: the writer can respond to the readers. This doesn’t work so well in a published book: this sort of interjection, rather than serving to keep the reader hooked, feels more like a constant distraction in a book not explicitly about food & sex. The reader’s already bought the book. They don’t need to be hooked again.

(Something of a counterexample: one of the most vexing things I found about Thomas de Zengatita’s Mediated (which we recently discussed at the Institute) was the style in which it’s written. Every page or so there’s a pithy, one-sentence paragraph. These zingers are employed over the 200 pages of the book; for the reader, it becomes immensely wearing. But just as a thought-experiment: if Zengotita had chopped the book up into page-sized chunks and turned it into a blog, the single-sentence zingers probably wouldn’t have been so bothersome; I might not have noticed them enough to comment on them. I’ve never found Zengatita’s much shorter essays in Harper’s annoyingly written. Some traits only becomes visible with length or time.)

While it’s very easy to fuse the words blog and book to get blook, that doesn’t automatically mean that a successful blog will become a successful book (or vice versa). These are very different forms. What could Julie Powell have learned from R. Kelly, besides any number of things which can’t be printed in a family-oriented blog? First, it’s a difficult job to make a coherent work out of unified pieces. It’s possible that R. Kelly could wrap up all of his narrative loose ends in future chapters, but I’m not holding my breath. Something else: even if it lacks any Aristotelian unities, “Trapped in the Closet” is interesting because it’s unique. Nobody else is making serialized pop music videos: we have nothing to judge it against, so it has novelty. (Yes, this might be damning with faint praise – that’s the other side of the coin.) A blog turned into a book doesn’t have that same sort of novelty. We end up judging it against the criteria by which we’d judge any other book – we compare Powell’s book to M. F. K. Fisher, though we wouldn’t have thought to do that with her blog. The blook inevitably suffers, because the content has been stuffed into a form which it doesn’t quite fit. Let blogs be blogs.

A question to throw out to end this with: could you develop the sort of big ideas that the physical book excels at moving around on a blog, given their modular construction?

class, cheating and gaming

The New York Times reports that a company in China is hiring people to play Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOG), like World of Warcraft or EverQuest. Employees develop avatars (or characters) and earn resources. Then, the company sells these efforts to affluent online gamers who do not have the time or inclination to play the early stages of the games themselves.

Finding hacks or ways to get around the intended game play is nothing new. I will confess that I have used cheat codes and hacks in playing video games. One of the first ones I’ve ever used, was in Super Mario Brothers on the original Nintendo Entertainment System. The Multiple 1-Ups: World 3-1 was a big favorite.

The article also briefly mentions something that I’ve been fascinated by: selling the results of your game play on auctions site, such as ebay. These services have turned game play into commodities, and we can actually determine valuations and costs of game play.

It made me to think about the character Hiro Protagonist in Neal Stephenson’s Snowcrash, a pizza delivery guy in the real world and lethal warrior in the “Metaverse.” He was an exception to the norm and socio-economic status usually carried over into the virtual reality because more realistic avatars were expensive. To actually see that happen in the game spaces of MMOGs by the purchasing of advanced players is quite amazing.

Why do I find that these gamers are cheating? In the era of non-linear information, I select and read only the parts of a text I deem to be relevant. I’ve skipped over parts of movies and watched another part again and again. Isn’t this the same thing? The troubling aspect of this phenomenon is that it is bringing class differentiation into game space. Although gaming itself is a leisure activity, the idea that you can spend your way into succeeding at a MMOG, removes my perceived innocence of that game space.

Intertextual Community

When I read about Shelly Jackson’s new project–to “publish” a story by tattooing each of its 2,095 words onto the body of a different person–I thought what a great idea, and I wondered if it might actually be telling us something about the direction books are going. As the digital book begins to emerge–glorious, ephemeral, and electric–are we going to feel compelled to make something even more intimate and rarified as counterpoint?

When I read about Shelly Jackson’s new project–to “publish” a story by tattooing each of its 2,095 words onto the body of a different person–I thought what a great idea, and I wondered if it might actually be telling us something about the direction books are going. As the digital book begins to emerge–glorious, ephemeral, and electric–are we going to feel compelled to make something even more intimate and rarified as counterpoint?

“Skin Literature”

Live from “Scholarship in the Digital Age” Conference at USC: The New Story

Scholarship in the Digital Age

This morning’s presentations got me thinking more about the narrative of the future–the multilayered, accreted story style that John Seely Brown referred to. How is that story going to be told and received? Will the novel become the dinosaur of alphabetic literacy?

Is the new book going to be a game, conversation, multi-layered, multi-authored, highly mutable and never-ending story? Assuming that the story is a conceptual device the culture uses to deconstruct reality, to make meaning, and to create, in some cases, a kind of anthem to rally around, what happens when our traditional narrative structures are replaced? If the single author, plot-driven novel is not the form of the future, then what do you get when you ask a million gamer/authors to shape an epic on the fly? What happens to our perception of reality if our stories are unstable, mutable, and open source?