The database:

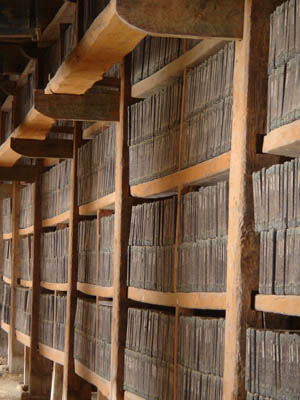

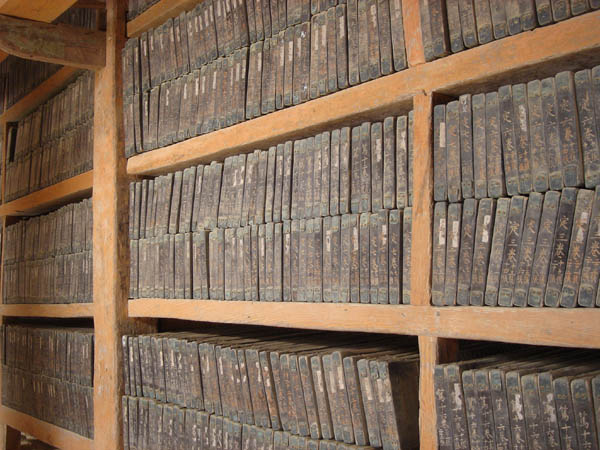

Nestled in the Gaya mountain range in southern Korea, the Haeinsa monastery houses the Tripitaka Koreana, the largest, most complete set of Buddhist scriptures in existence — over 80,000 wooden tablets (enough to print all of Buddhism’s sacred texts) kept in open-air storage for the past six centuries. The tablets were carved between 1237 and 1251 in anticipation of the impending Mongol invasion, both as a spiritual effort to ward off the attack, and as an insurance policy. They replaced an earlier set of blocks that had been destroyed in the last Mongol incursion in 1231.

From Korea’s national heritage site description of the tablets:

The printing blocks are some 70cm wide 24cm long and 2.8cm thick on the average. Each block has 23 lines of text, each with 14 characters, on each side. Each block thus has a total of 644 characters on both sides. Some 30 men carved the total 52,382,960 characters in the clean and simple style of Song Chinese master calligrapher Ou-yang Hsun, which was widely favored by the aristocratic elites of Goryeo. The carvers worked with incredible dedication and precision without making a single error. They are said to have knelt down and bowed after carving each character. The script is so uniform from beginning to end that the woodblocks look like the work of one person.

I stayed at the Haeinsa temple last Friday night on a sleeping mat in bare room with a heated floor, alongside a number of noisy Koreans (including the rather sardonic temple webmaster — Haiensa is a Unesco World Heritage site and so keeps a high profile). At three in the morning, at the call to the day’s first service, I tramped around the snowy courtyards under crisp, chill stars and watched as the monks pounded a massive barrel-shaped drum hanging inside a pagoda. This was for the benefit of those praying inside the temple (where it sounds like distant thunder). Shivering to the side, I continued to watch as they rang a bell the size of a Volkswagen with a polished log swung on ropes like a wrecking ball. Next to it, another monk ripped out a loud, clattering drum roll inside the wooden ribs of a dragon-like fish, also suspended from the pagoda’s roof. It was freezing cold with a biting wind — not pleasant to be outside, and at such an hour. But the stars were absolutely vivid. I’m no good at picking out constellations, but Orion was poised unmistakeably above the mountains as though stalking an elk on the other side of the ridge.

It’s a magical, somewhat harsh place, Haiensa. The Changgyeonggak, the two storage halls that house the Tripitaka, were built ingeniously to preserve the tablets by blocking wind, facilitating ventilation and distributing moisture. You see the monks busying themselves with devotions and chores, practicing an ancient way of life founded upon those tablets. The whole monastery a kind of computer, the monks running routines to and from the database. The mountains, Orion, the drum all part of the program. It seemed almost more hi-tech than cutting edge Seoul.

More on that later.

Category Archives: monastic

the light of the disk is endless

“The cover of the book was rubbed with a patina made from lamp black, Yakskin glue, and brains. It was burnished to a gloss and inscribed with an ink made from crushed pearls and silver.” That is a description of the one of the Tibetan monastic manuscripts, or pothi, that Jim Canary discussed in his recent presentation, “The Tibetan Book: From Pothi to Pixels and Back Again,” at The Changing Book Conference (University of Iowa). Pothi were originally made of palm leaves. They are up to four feet in length and thin in shape; consisting of loose leaves in cloth covers pressed between wooden boards. They are sometimes housed in wooden boxes that resemble child-sized coffins. The Tibetan pothi are stored in long, narrow pigeon holes built into the walls surrounding the chanting area of the temple. Jim showed us a picture of these impressive libraries, with ceilings so high, the walls, and their overstuffed catacombs, disappear into darkness.

Jim Canary has over sixty of hours of video, taken during his trips to Tibet, documenting the monastic printing process. He plans to edit and publish the video as a CD Rom in tandem with a print book. He showed us some selections, which I do not have, so I will do my best to describe them. Video #1: a man sits on the stone steps outside the temple. There are two tall stacks of paper next to him and a bowl of water in front of him. He is preparing the paper for printing, taking one sheet from the top of the pile, passing it through a pan of water and placing it on top of the other pile. He has hundreds of sheets to dampen, so he is working in a brisk rhythmic manner. When he’s finished, the stack will be pressed between two wooden blocks. Video #2: printing takes place in a building across from the temple. The printing is done in teams of two. One man holds the hand-carved wooden block and prepares it with ink. His partner places each damp sheet on the wooden block for burnishing, then removes it and sets it aside to dry. The men work quickly in tandem, surrounded by the music of monks chanting in the temple next door. The tone and rhythm of the chant matches the rhythm of their work. It is designed to correspond with the heart beat, and it works to knit all participants together into a single, metaphorical “body” which is, in turn, joined to all humanity through the meditation. The result of all this unity is a book, shaped like a body, which will be housed, along with hundreds of others, in the temple walls.

Mr. Canary’s presentation was also about the future of these mystical books, which are being cataloged, preserved, reproduced and distributed using digital technology. Some monks are now working on laptops, transcribing text and burning DVDs. Here is an excerpt from a poem written by one of the monks in praise of digital materials, which, in his eyes, are as exquiste as a patina made from lamp black, Yakskin glue, and brains, burnished to a gloss and inscribed with an ink made from crushed pearls and silver are to me.

…The light of the disk is endless

like the light of the disks in the sky, sun and moon.

With a single push of our finger on a button

We pull up the shining gems of text…

-Gelek Rinpoche