It’s not often that you see infographics with soul. Even though visuals are significantly more fun to look at than actual data tables, the oversimplification of infographics tends to suck out the interest in favor of making things quickly comprehensible (often to the detriment of the true data points, like the 2000 election map). This Röyksopp video, on the other hand, a delightful crossover between games, illustration, and infographic, is all about the storyline and subverts data to be a secondary player. This is not pure data visualization on the lines of the front page feature in USA Today. It is, instead, a touching story encased in the traditional visual language and iconography of infographics. The video’s currency belies its age: it won the 2002 MTV Europe music video award for best video.

Our information environment is growing both more dispersed and more saturated. Infographics serve as a filter, distilling hundreds of data points down into comprehensible form. They help us peer into the impenetrable data pools in our day to day life, and, in the best case, provide an alternative way to reevaluate our surroundings and make better decisions. (Tufte has also famously argued that infographics can be used to make incredibly poor decisions–caveat lector.)

But infographics do something else; more than visual representations of data, they are beautiful renderings of the invisible and obscured. They stylishly separate signal from noise, bringing a sense of comprehensive simplicity to an overstimulating environment. That’s what makes the video so wonderful. In the non-physical space of the animation, the datasphere is made visible. The ambient informatics reflect the information saturation that we navigate everyday (some with more serenity than others), but the woman in the video is unperturbed by the massive complexity of the systems that surround her. Her bathroom is part of a maze of municipal waterpipes; she navigates the public transport grid with thousands of others; she works at a computer terminal dealing with massive amounts of data (which are rendered in dancing—and therefore somewhat useless—infographics for her. A clever wink to the audience.); she eats food from a worldwide system of agricultural production that delivers it to her (as far as she can tell) in mere moments. This is the complexity that we see and we know and we ignore, just like her. This recursiveness and reference to the real is deftly handled. The video is designed to emphasize the larger picture and allows us to make connections without being visually bogged down in the particulars and textures of reality. The girl’s journey from morning to pint is utterly familiar, yet rendered at this larger scale and with the pointed clarity of a information graphic, the narrative is beautiful and touching.

via information aesthetics

Category Archives: media

wikipedia — mainstream media sighting

In his op-ed piece today, NY Times columnist, Paul Krugman, quotes from the Wikipedia to define conspiracy theory:

A conspiracy theory, says Wikipedia, “attempts to explain the cause of an event as a secret, and often deceptive, plot by a covert alliance.”

This is the first time I’ve seen the Wikipedia used as an authoritative reference in the Times or any other major media outlet.

blogburst

A small Austin, TX-based company called Pluck is launching a new blog aggregation service called BlogBurst that will filter postings from hundreds of approved bloggers and syndicate their content to major news services (and eventually smaller niche publications as well). Tomorrow, BlogBurst lets rip its fire hose of content at a handful of major newspapers including USA Today publisher Gannett Co., The Washington Post, The San Francisco Chronicle, and local pubs The Austin American-Statesman and San Antonio Express. Some are calling this a further blurring of the boundary between mainstream and independent medias. Seems to me more like an expansion of the umbrella of the former and a buttressing of the oft-lamented “power law” with regard to the latter (how the most popular blogs get entrenched in an “A-list” in spite of popular belief a level playing field). The AP has more.

Any blogger can sign up with BlogBurst but some editorial body there decides which blogs go into the syndication feed. Presumably, if the thing takes off, they’ll start breaking it up into multiple feeds — some generalized, some specialized. Participating publishers are povided with “editorial management tools” called the “publisher workbench.” So if I’m a newspaper, I receive a daily dump of thousands of blog postings, broken down into different topic areas. I fiddle around with those in the workbench, choose the ones I want, and then plug them into various slots in my paper. Technically, it works like this (warning, acroynum blitz):

Content from the BlogBurst network is easily integrated into your site via simple JavaScript calls or robust SOAP or XML APIs.

Incidentally, the name blogburst is a bit of co-opted net jargon describing any coordinated effort by bloggers to flood the web with postings on a particular topic — usually some hot-button issue like the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons. Search “blogburst” today on Technorati and you’ll find a slew of right wing bloggers on a “guard the borders” rhetorical rampage (ha! idealistic me, I initially thought they meant the borders between mainstream and grassroots media!).

Meanwhile, as I write, thousands march down Broadway in New York — blogging, as it were, with their feet — in support of America’s illegal immigrants.

I wonder how the two-capital-Bs BlogBurst will deal with the political polarization of blogs.

guardian launches huffingtonesque group blog

![]()

Living up to its reputation as the most innovative newspaper on the web, the Guardian yesterday launched an ambitious group blogging experiment – comment is free – that brings together a broad range of public intellectual types in a daily deluge of commentary and debate. Better designed than its acknowledged model, The Huffington Post, “comment is free” consists of three columns: new posts on the left, editors’ picks in the center, and links to the Guardian’s formal opinion pages on the right.

There are a few other tidbits: a political cartoon at the bottom of the page and a photo blog. Also this small nod toward the paper’s heritage, tucked beneath the cartoon, reminding us that comment may be free…

That’s CP Scott, The Guardian’s founder and editor for its first 57 years (it should read 1821) editor of The Guardian for 57 years beginning in 1872. This ties again to Jay Rosen’s post on newspapers as “seeders of clouds.”

knightfall

Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

Knight Ridder, America’s second largest newspaper company, operator of 32 dailies, has been purchased by McClatchy Co., a smaller newspaper company (reported here in the San Jose Mercury News, one of the papers McClatchy has acquired). Several months ago, Knight Ridder’s controlling shareholders, nervous about declining circulation and the increasing dominance of internet news, insisted that the company put itself up for auction. After being sniffed over and ultimately dropped by Gannett Co., the country’s largest print news conglomerate, the smaller McClatchy came through with KR’s sole bid.

McClatchy’s chief exec calls it: “a vote of confidence in the newspaper industry.” Or is it — to riff on the cultural environmentalism metaphor — like buying beach front property on the Aral Sea?

For a more hopeful view on the future of news, Jay Rosen (who has not yet commented on the Knight Ridder sale) has an amazing post today on Press Think about online newspapers as “seeders of clouds” and “public squares.” Very much worth a read.

thinking about blogging 2: democracy

Banning books may be easy, but banning blogs is an exhausting game of Whack-a-Mole for politically repressive regimes like China and Iran.

Farid Pouya, recapping recent noteworthy posts from the Iranian blogosphere last week on Global Voices, refers to one blogger’s observations on the chilled information climate under president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad:

Andishe No (means New Thought) fears that country was pushed back to pre Khatami’s period concerning censorship. He believes that even if many books get banned in twenty first century, government can not stop people getting information. Government wants to control weblogs in Iran and put them in a guideline.

Unlike the fleas that swarm American media and politics, Iran’s cyber-dissidents frequently are the sole conduit for uncensored information — an underground army of chiseler’s, typing away at the barricades. Here we see the blog as a building block for civil society. Electronic samizdat. Basic life forms in a free media ecology, instilling new habits in both writers and readers: habits of questioning, of digging deeper. Individual sites may get shut down, individual bloggers may be jailed but the information finds a way.

Though the situation in Iran is far from enviable, there is something attractive about the moral clarity of its dissident blogging. If one wants the truth, one must find alternatives — it’s that simple. But with alternative media in the United States — where the media ecology is highly developed and corruption more subtle — it’s hard to separate the wheat from the chaff. Political blogs in America may resound with outrage and indignation, but it’s the kind that comes from a life of abundance. All too often, political discourse is not something that points toward action, but an idle picking at the carcass of liberty.

Sure, we’ve seen blogs make a difference in politics (Swift Boats, Rathergate, Trent Lott — 2004 was the “year of the blog”), but generally as a furtherance of partisan aims — a way of mobilizing the groundtroops within a core constituency that has already decided what it believes.

When one looks at this map (admittedly a year old) of the American political blogosphere, one notes with dismay that there are in fact two spheres, mapping out all too cleanly to the polarized reality on the ground. One begins to suspect that America’s political blogs are merely a pressure valve for a population that, though ill at ease, is still ultimately paralyzed.

thinking about blogging 1: process versus product

Thinking about blogging: where’s it’s been and where it’s going. Recently I found food for thought in a smart but ultimately misguided essay by Trevor Butterworth in the Financial Times. In it, he decries blogging as a parasitic binge:

…blogging in the US is not reflective of the kind of deep social and political change that lay behind the alternative press in the 1960s. Instead, its dependency on old media for its material brings to mind Swift’s fleas sucking upon other fleas “ad infinitum”: somewhere there has to be a host for feeding to begin. That blogs will one day rule the media world is a triumph of optimism over parasitism.

While his critique is not without merit, Butterworth ultimately misses the forest for the fleas, fixating on the extremes of the phenomenon — the tiny tier of popular “establishment” bloggers and the millions of obscure hacks endlessly recycling news and gossip — while overlooking the thousands of mid-level blogs devoted to specialized or esoteric subjects not adequately covered — or not covered at all — by the press. Technorati founder David Sifry recently dubbed this the “magic middle” of the blogosphere — that group of roughly 150,000 sites falling somewhere between the short head and the long tail of the popularity graph. Notable as the establishment bloggers are, I would argue that it’s the middle stratum that has done the most in advancing serious discourse online. Here we are not talking about antagonism between big and small media, but rather a filling out of the media ecosystem — where a proliferation of niches, like pixels on a screen, improves the resolution of our image of the world.

So, naturalists observe, a flea

Hath smaller fleas that on him prey;

And these have smaller still to bite ’em;

And so proceed ad infinitum.

Thus every poet, in his kind,

Is bit by him that comes behind.

—Jonathan Swift

At their worst, bloggers — like Swift’s reiterative fleas — bounce ineffectually off the press’s opacities. But sometimes the collective feeding frenzy can expose flaws in the system. Moreover, there are some out there that have the knowledge and insight to decode what the press reports yet fails to adequately analyze. And there others still who are not tied so inexorably to the news cycle but follow their own daemon.

To me, Swift’s satire, while humorously portraying the endless cycle of literary derivation, also suggests a healthier notion of process — less parasitic and more cumulative. At best transformative. The natural accretion over time of ideas and tradition. It’s only natural that poets build — or feed — on the past. They feel the nip at their behinds. They channel and reinvent. As do scholars and philosophers.

But having some expertise and knowing how to craft a sentence does not necessarily mean one is meant to blog. In an amusing passage, Butterfield speculates on how things might how gone horribly awry had George Orwell (oft hailed as a proto-blogger) been given the opportunity to maintain a daily journal online (think tedious rambling on the virtues of English cuisine). Good blogging requires not only a voice, but a special commitment — a compulsion even — to air one’s thinking in real time. A relish for working through ideas in the open, often before they’re fully baked.

But evidently Butterfield hasn’t considered the merits of blogging as a process. He remains terminally hung up on the product, concluding that blogging “renders the word even more evanescent than journalism” and is “the closest literary culture has come to instant obsolescence.” Fine. Blogging is in many ways a vaporous pursuit, but then so is conversation — so is theatre. Blogging, in its essence, is about discussion and about working through ideas. And, I would argue, it is as much about reading as it is about writing.

Back in August, I wrote about this notion of the blog as a record of reading — an idea to which I still hold fast. The blog is a tool (for writers and readers alike) for dealing with information overload — for processing an unmanageable abundance of reading material. Most bloggers, the good ones anyway, not only point to links (though the good pointer sites like Arts & Letters Daily are invaluable), they comment upon them (as I am doing here), glossing them for their readers, often quoting at length. The blog captures that wave of energy emitted by the reader’s mind upon contact with an idea or story.

I do think blogging goes a significant ways toward the Enlightenment ideal of a reading public, even if only one percent of that public is worth reading. Hemingway famously said that he wrote 99 pages of crap for every one page of masterpiece. We should apply a similar math to blogs, and hope the tools for filtering out that 99 percent improve over time. After all, one percent of 28 million is no small number (about the population of Buffalo, NY). I’m confident that, in aggregate, this small democratic layer illumines more than it obscures, blazing trails of readings and fostering conversation. And this, I would venture — when combined and balanced with more traditional media sources — offers a more balanced reading diet.

lessig: read/write internet under threat

In an important speech to the Open Source Business Conference in San Francisco, Lawrence Lessig warned that decreased regulation of network infrastructure could fundamentally throw off the balance of the “read/write” internet, gearing the medium toward commercial consumption and away from creative production by everyday people. Interestingly, he cites Apple’s iTunes music store, generally praised as the shining example of enlightened digital media commerce, as an example of what a “read-only” internet might look like: a site where you load up your plate and then go off to eat alone.

Lessig is drawing an important connection between the question of regulation and the question of copyright. Initially, copyright was conceived as a way to stimulate creative expression — for the immediate benefit of the author, but for the overall benefit of society. But over the past few decades, copyright has been twisted by powerful interests to mean the protection of media industry business models, which are now treated like a sacred, inviolable trust. Lessig argues that it’s time for a values check — time to return to the original spirit of copyright:

It’s never been the policy of the U.S. government to choose business models, but to protect the authors and artists… I’m sure there is a way for [new models to emerge] that will let artists succeed. I’m not sure we should care if the record companies survive. They care, but I don’t think the government should.

Big media have always lobbied for more control over how people use culture, but until now, it’s largely been through changes to the copyright statutes. The distribution apparatus — record stores, booksellers, movie theaters etc. — was not a concern since it was secure and pretty much by definition “read-only.” But when we’re dealing with digital media, the distribution apparatus becomes a central concern, and that’s because the apparatus is the internet, which at present, no single entity controls.

Which is where the issue of regulation comes in. The cable and phone companies believe that since it’s through their physical infrastructure that the culture flows, that they should be able to control how it flows. They want the right to shape the flow of culture to best fit their ideal architecture of revenue. You can see, then, how if they had it their way, the internet would come to look much more like an on-demand broadcast service than the vibrant two-way medium we have today: simply because it’s easier to make money from read-only than from read/write — from broadcast than from public access.”

Control over culture goes hand in hand with control over bandwidth — one monopoly supporting the other. And unless more moderates like Lessig start lobbying for the public interest, I’m afraid our government will be seduced by this fanatical philosophy of control, which when aired among business-minded people, does have a certain logic: “It’s our content! Our pipes! Why should we be bled dry?” It’s time to remind the media industries that their business models are not synonymous with culture. To remind the phone and cable companies that they are nothing more than utility companies and that they should behave accordingly. And to remind the government who copyright and regulation are really meant to serve: the actual creators — and the public.

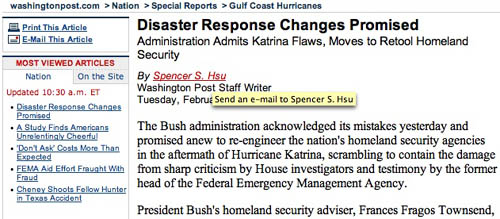

washington post and new york times hyperlink bylines

In an effort to more directly engage readers, two of America’s most august daily newspapers are adding a subtle but potentially significant feature to their websites: author bylines directly linked to email forms. The Post’s links are already active, but as of this writing the Times, which is supposedly kicking off the experiment today, only links to other articles by the same reporter. They may end up implementing this in a different way.

screen grab from today’s Post

The email trial comes on the heels of two notoriously failed experiments by elite papers to pull readers into conversation: the LA Times’ precipitous closure, after an initial 24-hour flood of obscenities and vandalism, of its “wikatorials” page, which invited readers to rewrite editorials alongside the official versions; and more recently, the Washington Post’s shutting down of comments on its “post.blog” after experiencing a barrage of reader hate mail. The common thread? An aversion to floods, barrages, or any high-volume influx of unpredictable reader response. The email features, which presumably are moderated, seem to be the realistic compromise, favoring the trickle over the deluge.

In a way, though, hyperlinking bylines is a more profound development than the higher profile experiments that came before, which were more transparently about jumping aboard the wiki/blog bandwagon without bothering to think through the implications, or taking the time — as successful blogs and wikis must always do — to gradually build up an invested community of readers who will share the burden of moderating the discussion and keeping things reasonably clean. They wanted instant blog, instant wiki. But online social spaces are bottom-up enterprises: invite people into your home without any preexisting social bonds and shared values — and add to that the easy target of being a mass media goliath — and your home will inevitably get trashed as soon as word gets out.

Being able to email reporters, however, gets more at the root of the widely perceived credibility problem of newspapers, which have long strived to keep the human element safely insulated behind an objective tone of voice. It’s certainly not the first time reporters’ or columnists’ email addresses have been made available, but usually they get tucked away toward the bottom. Having the name highlighted directly beneath the headline — making the reporter an interactive feature of the article — is more genuinely innovative than any tacked-on blog because it places an expectation on the writers as well as the readers. Some reporters will likely treat it as an annoying new constraint, relying on polite auto-reply messages to maintain a buffer between themselves and the public. Others may choose to engage, and that could be interesting.

what I heard at MIT

Over the next few days I’ll be sifting through notes, links, and assorted epiphanies crumpled up in my pocket from two packed, and at times profound, days at the Economics of Open Content symposium, hosted in Cambridge, MA by Intelligent Television and MIT Open CourseWare. For now, here are some initial impressions — things I heard, both spoken in the room and ricocheting inside my head during and since. An oral history of the conference? Not exactly. More an attempt to jog the memory. Hopefully, though, something coherent will come across. I’ll pick up some of these threads in greater detail over the next few days. I should add that this post owes a substantial debt in form to Eliot Weinberger’s “What I Heard in Iraq” series (here and here).

![]()

Naturally, I heard a lot about “open content.”

I heard that there are two kinds of “open.” Open as in open access — to knowledge, archives, medical information etc. (like Public Library of Science or Project Gutenberg). And open as in open process — work that is out in the open, open to input, even open-ended (like Linux, Wikipedia or our experiment with MItch Stephens, Without Gods).

I heard that “content” is actually a demeaning term, treating works of authorship as filler for slots — a commodity as opposed to a public good.

I heard that open content is not necessarily the same as free content. Both can be part of a business model, but the defining difference is control — open content is often still controlled content.

I heard that for “open” to win real user investment that will feedback innovation and even result in profit, it has to be really open, not sort of open. Otherwise “open” will always be a burden.

I heard that if you build the open-access resources and demonstrate their value, the money will come later.

I heard that content should be given away for free and that the money is to be made talking about the content.

I heard that reputation and an audience are the most valuable currency anyway.

I heard that the academy’s core mission — education, research and public service — makes it a moral imperative to have all scholarly knowledge fully accessible to the public.

I heard that if knowledge is not made widely available and usable then its status as knowledge is in question.

I heard that libraries may become the digital publishing centers of tomorrow through simple, open-access platforms, overhauling the print journal system and redefining how scholarship is disseminated throughout the world.

![]()

And I heard a lot about copyright…

I heard that probably about 50% of the production budget of an average documentary film goes toward rights clearances.

I heard that many of those clearances are for “underlying” rights to third-party materials appearing in the background or reproduced within reproduced footage. I heard that these are often things like incidental images, video or sound; or corporate logos or facades of buildings that happen to be caught on film.

I heard that there is basically no “fair use” space carved out for visual and aural media.

I heard that this all but paralyzes our ability as a culture to fully examine ourselves in terms of the media that surround us.

I heard that the various alternative copyright movements are not necessarily all pulling in the same direction.

I heard that there is an “inter-operability” problem between alternative licensing schemes — that, for instance, Wikipedia’s GNU Free Documentation License is not inter-operable with any Creative Commons licenses.

I heard that since the mass market content industries have such tremendous influence on policy, that a significant extension of existing copyright laws (in the United States, at least) is likely in the near future.

I heard one person go so far as to call this a “totalitarian” intellectual property regime — a police state for content.

I heard that one possible benefit of this extension would be a general improvement of internet content distribution, and possibly greater freedom for creators to independently sell their work since they would have greater control over the flow of digital copies and be less reliant on infrastructure that today only big companies can provide.

I heard that another possible benefit of such control would be price discrimination — i.e. a graduated pricing scale for content varying according to the means of individual consumers, which could result in fairer prices. Basically, a graduated cultural consumption tax imposed by media conglomerates

I heard, however, that such a system would be possible only through a substantial invasion of users’ privacy: tracking users’ consumption patterns in other markets (right down to their local grocery store), pinpointing of users’ geographical location and analysis of their socioeconomic status.

I heard that this degree of control could be achieved only through persistent surveillance of the flow of content through codes and controls embedded in files, software and hardware.

I heard that such a wholesale compromise on privacy is all but inevitable — is in fact already happening.

I heard that in an “information economy,” user data is a major asset of companies — an asset that, like financial or physical property assets, can be liquidated, traded or sold to other companies in the event of bankruptcy, merger or acquisition.

I heard that within such an over-extended (and personally intrusive) copyright system, there would still exist the possibility of less restrictive alternatives — e.g. a peer-to-peer content cooperative where, for a single low fee, one can exchange and consume content without restriction; money is then distributed to content creators in proportion to the demand for and use of their content.

I heard that such an alternative could theoretically be implemented on the state level, with every citizen paying a single low tax (less than $10 per year) giving them unfettered access to all published media, and easily maintaining the profit margins of media industries.

I heard that, while such a scheme is highly unlikely to be implemented in the United States, a similar proposal is in early stages of debate in the French parliament.

![]()

And I heard a lot about peer-to-peer…

I heard that p2p is not just a way to exchange files or information, it is a paradigm shift that is totally changing the way societies communicate, trade, and build.

I heard that between 1840 and 1850 the first newspapers appeared in America that could be said to have mass circulation. I heard that as a result — in the space of that single decade — the cost of starting a print daily rose approximately %250.

I heard that modern democracies have basically always existed within a mass media system, a system that goes hand in hand with a centralized, mass-market capital structure.

I heard that we are now moving into a radically decentralized capital structure based on social modes of production in a peer-to-peer information commons, in what is essentially a new chapter for democratic societies.

I heard that the public sphere will never be the same again.

I heard that emerging practices of “remix culture” are in an apprentice stage focused on popular entertainment, but will soon begin manifesting in higher stakes arenas (as suggested by politically charged works like “The French Democracy” or this latest Black Lantern video about the Stanley Williams execution in California).

I heard that in a networked information commons the potential for political critique, free inquiry, and citizen action will be greatly increased.

I heard that whether we will live up to our potential is far from clear.

I heard that there is a battle over pipes, the outcome of which could have huge consequences for the health and wealth of p2p.

I heard that since the telecomm monopolies have such tremendous influence on policy, a radical deregulation of physical network infrastructure is likely in the near future.

I heard that this will entrench those monopolies, shifting the balance of the internet to consumption rather than production.

I heard this is because pre-p2p business models see one-way distribution with maximum control over individual copies, downloads and streams as the most profitable way to move content.

I heard also that policing works most effectively through top-down control over broadband.

I heard that the Chinese can attest to this.

I heard that what we need is an open spectrum commons, where connections to the network are as distributed, decentralized, and collaboratively load-sharing as the network itself.

I heard that there is nothing sacred about a business model — that it is totally dependent on capital structures, which are constantly changing throughout history.

I heard that history is shifting in a big way.

I heard it is shifting to p2p.

I heard this is the most powerful mechanism for distributing material and intellectual wealth the world has ever seen.

I heard, however, that old business models will be radically clung to, as though they are sacred.

I heard that this will be painful.