The first machinima festival to be held in Europe took place at DMU in Leicester – and in Second Life – on 12-14 October. This quickly-growing genre fuses film-making and computer gaming to provide a quick and cost-effective way to create animated films. Bob Stein’s interview in This Spartan Life is a wonderful example.

Best Experimental award went to Cirque du Machinima: Cuckoo Clock by Tom Jantol of Croatia. it’s great to see something made in this way which has such a thoroughly non-Hollywood aesthetic. There’s amazing potential here for writers – and readers – to create visualisations of work without teams of techies and budgets of millions.

Category Archives: machinima

mckenzie wark interview in halo

This interview with McKenzie Wark was conducted inside an online version of the Halo 2 video game as part of the upcoming fourth episode of This Spartan Life, “a talk show in gamespace.” Many thanks to Chris Burke and the TSL team for doing such a fantastic job. Click the image to play (it’s a little under 14 minutes):

From the interview, here’s McKenzie on collaborating with readers inside his book:

“It sort of brings out what writing always is anyway, which is that, in a sense, you’re always the DJ of other people’s thoughts and ideas, and this just makes that manifest.”

Also see this interesting thread in the GAM3R 7H30RY forum from a while back — a discussion between McKenzie and Chris about “glitching” and other forms of trifling or hacking within the game (the bread and butter of machinima filmmakers), and whether this can lead to real freedom. There’s a moment later on in the video where the debate gets wonderfully concretized in the physical landscape of the game world.

We “shot” the footage back in August at Chris’s studio in Brooklyn. I managed to snap a couple of hazy pictures with my camera phone:

On the left you see the room where Chris and the two camera operators have their consoles. On the right is McKenzie in his own little cave. Everything is recorded through video feeds running out of the Xboxes. Ken and Chris talk over headsets and move around the game environment while the two “cameras” follow behind (the cameras are just the perspectives of the other two gamers). The chaos during Ken’s reading at the end is the work of other online gamers from around the country — TSL groupies who like helping out with shoots and generally raising hell. Seeing Chris try to coordinate this rambunctious crew long distance was highly entertaining.

(If you haven’t seen it, also check out This Spartan Life’s interview with Bob from their first episode. A real treat.)

machinima agitprop elucidates net neutrality

This Spartan Life, our favorite talk show in Halo space, just posted a hilarious video blog entry making the case for network neutrality. In some ways, this is the perfect medium for illustrating a threat to virtual spaces, conveying more in a couple of minutes than several weeks worth of op-eds. Enjoy it now before the party’s over.

(In case you missed it, here’s TSL’s interview with Bob.)

war machinima

Ray, Bob and I spent last week out in Los Angeles at our institutional digs (the Annenberg Center for Communication at USC), where we held a pair of meetings with professors from around the US and Canada to discuss various coups we are attempting to stage within the ossified realm of scholarly and textbook publishing. Following these, we were able to stick around for a fun conference/media festival organized by Annenberg’s Networked Publics project.

The conference was a mix of the usual academic panels and a series of curated mini-exhibits of “do-it-yourself” media, surveying new genres of digital folk art currently proliferating across the net such as political remix movies, anime music videos, “digital handmade” art projects (which featured the near and dear Alex Itin — happy birthday, Alex!), and of course, machinima: films made inside of video game engines.

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

As we enjoyed this little feast of new media, I was vaguely aware that the Tribeca film festival was going on back in New York. As I casually web-surfed through one of the panels — in the state of continuous partial attention that is now the standard state of being all these networky conferences — I came across an article about one of the more talked about films appearing there this year: “The War Tapes.” Like Gunner Palace and Occupation Dreamland, “The War Tapes” is a documentary about American soldiers in Iraq, but with one crucial difference: all the footage was shot by actual soldiers.

Back in 2004, director Deborah Scranton gave video cameras to ten members of the New Hampshire National Guard who were about to depart for a yearlong tour in Iraq. They went on to shoot a combined 800 hours of film, the pared-down result of which is “The War Tapes.” Reading about it, I couldn’t help but think that here was a case of real-life machinima. Give the warriors cameras and glimpse the war machine from the inside — carve out a new game within the game.

Granted, it’s a far from perfect analogy. Machinima involves a total repurposing of the characters and environment, foregoing the intended objectives of the game. In “The War Tapes,” the soldiers are still on their mission, still within the chain of command. And of course, war isn’t a video game. But isn’t it advertised as one?

Time Square, New York City (the military-entertainment complex)

There’s something undeniably subversive about giving cameras to GIs in what is such a thoroughly mediated war, a sort of playing against the game — if not of the game of occupation as a whole, then at least the game of spin. “I’m not supposed to talk to the media,” says one soldier to Steve Pink, one of the film’s main subjects, as he attempts to conduct an interview. To which Pink replies: “I’m not the media, dammit!”

In the clips I found on the film’s promotional site (the general release is later this summer), the overriding impression is of the soldiers’ isolation and fear: the constant terror of roadside bombs, frantic rounds fired into the green night-vision darkness, swaddled in helmets and humvees and hi-tech weaponry. It’s a frightening game they play. Deeply impersonal and anonymous, and in no way resembling the pumped-up, guitar-screeching game that the military portrays as war in its recruiting ads. This is the horrible truth at the bottom of the “Army of One” slogan: you are a lone digit in a massive calculation. Just pray you don’t become a zero.

Yet naturally, they find their own games to play within the game. One clip shows the tiny, gruesome spectacle of two soldiers, in a moment of leisure, pitting a scorpion against a spider inside a plastic tub, reenacting their own plight in the language of the desert.

At the Net Publics conference, we did see see one example of genuine machinima that made its own spooky commentary on the war: a hack of Battlefield 2 by Swedish game forum Snoken that brilliantly apes the now-famous Sony Bravia commercial, in which 250,000 colored plastic balls were filmed cascading through the streets of a San Francisco.

Here’s Battlefield:

And here’s the original Sony ad:

McKenzie Wark doesn’t address machinima in GAM3R 7H30RY (which launches in about a week), but he does discuss video games in the context of the “military entertainment complex”: the remaking of postmodern capitalist society in the image of the digital game, in which every individual is a 1 or a 0 locked in senseless competition for advancement through the levels, each vying to “win” the game:

The old class antagonisms have not gone away, but are hidden beneath levels of rank, where each agonizes over their worth against others in the price of their house, the size of their vehicle and where, perversely, working longer and longer hours is a sign of winning the game. Work becomes play. Work demands not just one’s mind and body but also one’s soul. You have to be a team player. Your work has to be creative, inventive, playful – ludic, but not ludicrous.

Video games (which can actually be won) are allegories of this imperfect world that we are taught to play like a game, as though it really were governed by a perfect (and perfectly fair) algorithm — even the wars that rage across its hemispheres:

Once games required an actual place to play them, whether on the chess board or the tennis court. Even wars had battle fields. Now global positioning satellites grid the whole earth and put all of space and time in play. Warfare, they say, now looks like video games. Well don’t kid yourself. War is a video game – for the military entertainment complex. To them it doesn’t matter what happens ‘on the ground’. The ground – the old-fashioned battlefield itself – is just a necessary externality to the game. Slavoj Zizek: “It is thus not the fantasy of a purely aseptic war run as a video game behind computer screens that protects us from the reality of the face to face killing of another person; on the contrary it is this fantasy of face to face encounter with an enemy killed bloodily that we construct in order to escape the Real of the depersonalized war turned into an anonymous technological operation.” The soldier whose inadequate armor failed him, shot dead in an alley by a sniper, has his death, like his life, managed by a computer in a blip of logistics.

How does one truly escape? Ultimately, Wark’s gamer theory is posed in the spirit that animates the best machinima:

The gamer as theorist has to choose between two strategies for playing against gamespace. One is to play for the real. (Take the red pill). But the real is nothing but a heap of broken images. The other is to play for the game (Take the blue pill). Play within the game, but against gamespace. Be ludic, but also lucid.

machinima: a call for papers and some thoughts on defining a form

Grand Text Auto reports a call for proposals for essays to be included in a reader on machinima. Most often, machinima is the repurposing of video gameplay that is recorded and then re-edited, with additional sound and voice over.

People have been creating machinima with 3D video games, such as Quake, since the late 1990s. Even before that, in the late 80s, my friends and I would record our Nintendo victories on VHS, more in the spirit of DIY skate videos. However, in the last few years, the machinima community has seen tremendous growth, which coincided with the penetration of video editing equipment in the home. What started as ironic short movies have started to grow into fairly elaborate projects.

Until the last few years, social research on games in general was limited and sporadic. In the 1970s and 1980s, the University of Pennsylvania was the rare institution that supported a community of scholars to investigate games and play. A vast proliferation of book and social research exists on gaming and especially video games, which we have discussed here.

Although I love machinima, I am surprised as to how quickly a reader is being produced. Machinima is still a rather fringe phenomena, albeit growing. My first reaction is that machinima is not exactly ready for an entire reader on the subject. I look forward to being surprised by the final selection of essays.

Part of this reaction comes from the notion that machinima is a rather limited form. In my mind, machinima is the repurposing of video game output. However, machinima.org emphasizes capturing live action/ real time digital animation as an essential part of the form, thereby removing the necessity of the video game. Most machinima is created within the virtual video gaming environment because that is where people are able to most readily control and capture 3D animation in real time. Live action or real time capture is different from traditional 3D animation tools (for instance Maya) where you program (and hence control) the motion of your object, background, and camera before you render (or record) the animation rather than during as in machinima.

Broadening of the definition of machinima, as with any form, plays a role on the sustainability of the form. For example, in looking at painting versus sculpture, painting seems to confine what is considered “painting” to pigment on a 2D surface. Where more expansive interpretations of the form get new labeling such as mixed media or multimedia. On the other hand, sculpture has expanded beyond traditional materials of wood, metal, and stone. Thus, the art of James Turrell, who works with landscape, light and interior space can be called sculpture. I do not imply that painting is by any means dead. The 2004 Whitney Biennal had a surprisingly rich display of painting and drawing, as well as photography. However, note the distinction that photography is not considered painting, although photography is 2D medium.

The word machinima comes from combining machine cineama or machine animation. This foundation does pose limits to how far beyond repurposing video game output machinima can go. It is not convincing to try to include the repurposing of traditional film and animation under the label of machinima. Clearly, repurposing material such as japanese movies or cartoons as in Woody Allen’s “What’s Up, Tigerlily?” and the Cartoon Network’s “Sealab 2021” is not machinima. Further more, I am hesitant to call the repurposing of a digital animation machinima. I am not familiar with any examples, but I would not be surprised if they exist.

With the release of The Movies, people can use the game’s 3D modeling engine to create wholly new movies. It is not readily clear to me, if The Movies allows for real time control of it’s characters. If it does, then “French Democracy” (the movie made by French teenagers about the Parisian riots in late 2005) should be considered machinima. However, if it does not, then I cannot differentiate the “French Democracy” from films made in Maya or Pixar in-house applications. Clearly, Pixar’s “Toy Story” is not machinima.

As digital forms emerge, the boundaries of our mental constructions guide our understanding and discourse surrounding these forms. I’m realizing that how we define these constructions control not only the relevance but also the sustainability of these forms. Machinima defined solely as repurposed video game output is limiting, and utlimately less interesting than the potential of capturing real time 3D modeling engines as a form of expression, whatever we end up calling it.

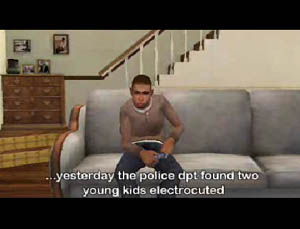

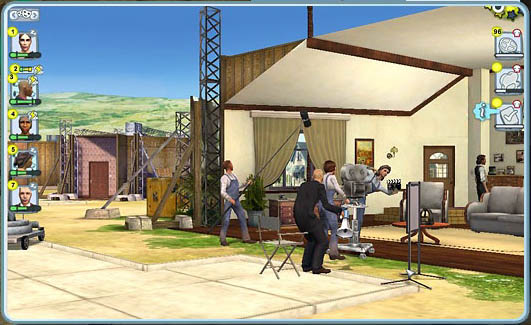

machinima’s new wave

“The French Democracy” (also here) is a short film about the Paris riots made entirely inside of a computer game. The game, developed by Peter Molyneux‘s Lionhead Productions and called simply “The Movies,” throws players into the shark pool of Hollywood where they get to manage a studio, tangle with investors, hire and fire actors, and of course, produce and distribute movies. The interesting thing is that the movie-making element has taken on a life of its own as films produced inside the game have circulated through the web as free-standing works, generating their own little communities and fan bases.

This is a fascinating development in the brief history of Machinima, or “machine cinema,” a genre of films created inside the engines of popular video game like Halo and The Sims. Basically, you record your game play through a video out feed, edit the footage, and add music and voiceovers, ending up with a totally independent film, often in funny or surreal opposition to the nature of the original game. Bob, for instance, appeared in a Machinima talk show called This Spartan Life, where they talk about art, design and philosophy in the bizarre, apocalyptic landscapes of the Halo game series.

The difference here is that while Machinima is typically made by “hacking” the game engine, “The Movies” provides a dedicated tool kit for making video game-derived films. At the moment, it’s fairly primitive, and “The French Democracy” is not as smooth as other Machinima films that have painstakingly fitted voice and sound to create a seamless riff on the game world. The filmmaker is trying to do a lot with a very restricted set of motifs, unable to add his/her own soundtrack and voices, and having only the basic menu of locales, characters, and audio. The final product can feel rather disjointed, a grab bag of film clichés unevenly stitched together into a story. The dialogue comes only in subtitles that move a little too rapidly, Paris looks suspiciously like Manhattan, and the suburbs, with their split-level houses, are unmistakably American.

But the creative effort here is still quite astonishing. You feel you are seeing something in embryo that will eventually come into its own as a full-fledged art form. Already, “The Movies” online community is developing plug-ins for new props, characters, environments and sound. We can assume that the suite of tools, in this game and elsewhere, will only continue to improve until budding auteurs really do have a full virtual film studio at their disposal.

It’s important to note that, according to the game’s end-user license agreement, all movies made in “The Movies” are effectively owned by Activision, the game’s publisher. Filmmakers, then, can aspire to nothing more than pro-bono promotional work for the parent game. So for a truly independent form to emerge, there needs to be some sort of open-source machinima studio where raw game world material is submitted by a community for the express purpose of remixing. You get all the fantastic puppetry of the genre but with no strings attached.