On Monday, Adriene Jenik, who is Associate Professor of Computer & Media Arts at UC San Diego, stopped by for what turned into an interesting discussion on the future of libraries. Adriene is a telecommunications media artist who has experimented extensively in virtual performance with projects like Desktop Theater and SPECFLIC, an ongoing “speculative distributed cinema project.”

More recently, she wrote and produced SPECFLIC 2.0, which explores the intersection of digital media, books, and reading. With the help of a large network of collaborating artists, Jenik transformed the Martin Luther King Library in San Jose into a one night only vision of the future called the InfoSphere, where a computerized reference librarian called The Infospherian provides an interface to all the bits of information what anyone might need, and is in charge of issuing and enforcing reading licenses to the public.

Before the group got to discussing how libraries where changing, Adriene and I first discussed how neighborhoods and cities develop; the way growth is encouraged and discouraged in certain areas, and of those who benefit from seeing either scenario play out.

As in the discussion we had about neighborhoods, I am ambivalent towards the way libraries are changing. People use search engines to find information quickly and are less frequently doing research in libraries. In fact, even in libraries computer labs tend to be the most populous rooms. The act of looking through physical books lends itself well to serendipitous discoveries, and while I agree that many of these kinds of experiences may be lost, it’s hard to really know for sure what is gained and what is lost when you’re in the midst of change.

For better or worse, as a tool, the library, as we know it today, appears to have lived out it’s life. In the future, the idea of a library as a museum, as opposed to an active location like a park makes a lot more sense to me. Something will be lost with the transition, that is for sure, and as much of it as possible should be preserved, but it’s hard to see today’s library being able to compete with the technologies of the future in the same way.

What I find bizarre about all this is that when you walk into a Barnes & Noble all the seats are taken, so it seems that “reading buildings” of some sort have some demand. Maybe it’s the social setting or maybe it’s the Starbucks. Actually, that could be the future of the library: a big empty building that people bring their electronic books to so that they can read and drink their coffee in a social setting… quietly.

“No analog book allowed inside library. Please digitize your analog book at the door.”

Category Archives: library

microsoft steps up book digitization

Back in June, Microsoft struck deals with the University of California and the University of Toronto to scan titles from their nearly 50 million (combined) books into its Windows Live Book Search service. Today, the Guardian reports that they’ve forged a new alliance with Cornell and are going to step up their scanning efforts toward a launch of the search portal sometime toward the beginning of next year. Microsoft will focus on public domain works, but is also courting publishers to submit in-copyright books.

Making these books searchable online is a great thing, but I’m worried by the implications of big coprorations building proprietary databases of public domain works. At the very least, we’ll need some sort of federated book search engine that can leap the walls of these competing services, matching text queries to texts in Google, Microsoft and the Open Content Alliance (which to my understanding is mostly Microsoft anyway).

But more important, we should get to work with OCR scanners and start extracting the texts to build our own databases. Even when they make the files available, as Google is starting to do, they’re giving them to us not as fully functioning digital texts (searchable, remixable), but as strings of snapshots of the scanned pages. That’s because they’re trying to keep control of the cultural DNA scanned from these books — that’s the value added to their search service.

But the public domain ought to be a public trust, a cultural infrastructure that is free to all. In the absence of some competing not-for-profit effort, we should at least start thinking about how we as stakeholders can demand better access to these public domain works. Microsoft and Google are free to scan them, and it’s good that someone has finally kickstarted a serious digitization campaign. It’s our job to hold them accountable, and to make sure that the public domain doesn’t get redefined as the semi-public domain.

books in time

This morning I’m giving a talk on networked books at a libraries and technology conference up at Bentley College, just outside of Boston. The program, “Social Networking: Plugging New England Libraries into Web 2.0,” has been organized by NELINET, a consortium of over 600 academic, public and special libraries across the six New England states, so librarians and info services folks from all over the northeast will be in attendance.

In many ways, our publishing projects fit quite comfortably under the broad, buzz-ridden rubrique of Web 2.0: books as social spaces, “architecture of participation,” “treat your users as co-developers” (or, in our experiments, readers as co-authors). I’m going to be discussing all of these things, but I’m also planning to look at books in a slightly different way: as processes, or movements, in time.

Lately, when we’re explaining our work to the unitiated, Bob picks up whatever book is lying nearby (yes, we do have books), holds it up in the air and indicates with his hands the space on either side of the object: “here’s all the stuff that came before the book, and here’s all the stuff that came after.” That’s the spectrum that networked reading and writing opens up, and what the Institute are trying to do is to explore and open up new ways of thinking about all these different stages of creative flow that go into and out of books. Of our recent projects, you could say that Without Gods focuses on the “into” end of the evolutionary span while GAM3R 7H30RY deals more with the “out of.” Naturally, books have always been this way, but computers and networks make all of it manifest in a very new way that’s difficult to make sense of.

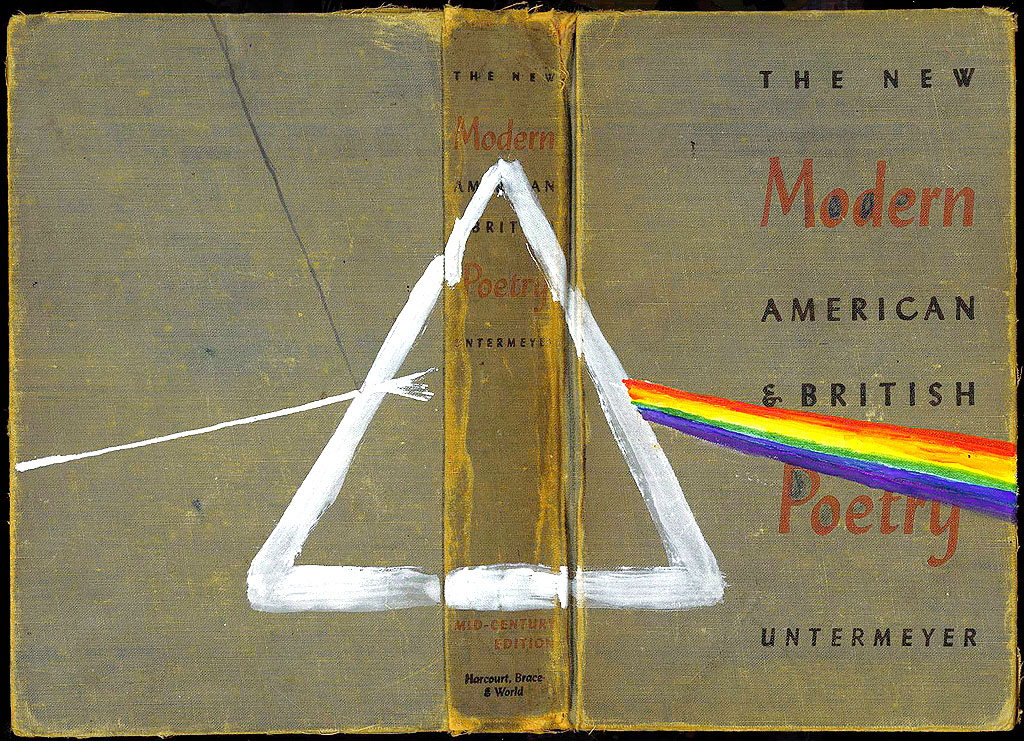

That’s what the picture up top is getting at, in a joshing way. Bob’s depiction of books in time reminded me of the famous prism image on the cover of Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon” where pure white light turns to rainbow as it passes through the glass. I was joking about this with Alex Itin, our artblogger in residence, and yesterday he cobbled together this excellent image (and ripped the audio), which I’m going to work into my talk somehow. Wish me luck.

(Incidentally, “Books in Time” is the name of a wonderful essay by Carla Hesse, a Berkeley historian, which has been a big influence on what we do.)

google and the future of print

Veteran editor and publisher Jason Epstein, the man who first introduced paperbacks to American readers, discusses recent Google-related books (John Battelle, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, David Vise etc.) in the New York Review, and takes the opportunity to promote his own vision for the future of publishing. As if to reassure the Updikes of the world, Epstein insists that the “sparkling cloud of snippets” unleashed by Google’s mass digitization of libraries will, in combination with a radically decentralized print-on-demand infrastructure, guarantee a bright future for paper books:

[Google cofounder Larry] Page’s original conception for Google Book Search seems to have been that books, like the manuals he needed in high school, are data mines which users can search as they search the Web. But most books, unlike manuals, dictionaries, almanacs, cookbooks, scholarly journals, student trots, and so on, cannot be adequately represented by Googling such subjects as Achilles/wrath or Othello/jealousy or Ahab/whales. The Iliad, the plays of Shakespeare, Moby-Dick are themselves information to be read and pondered in their entirety. As digitization and its long tail adjust to the norms of human nature this misconception will cure itself as will the related error that books transmitted electronically will necessarily be read on electronic devices.

Epstein predicts that in the near future nearly all books will be located and accessed through a universal digital library (such as Google and its competitors are building), and, when desired, delivered directly to readers around the world — made to order, one at a time — through printing machines no bigger than a Xerox copier or ATM, which you’ll find at your local library or Kinkos, or maybe eventually in your home.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Predicated on the “long tail” paradigm of sustained low-amplitude sales over time (known in book publishing as the backlist), these machines would, according to Epstein, replace the publishing system that has been in place since Gutenberg, eliminating the intermediate steps of bulk printing, warehousing, retail distribution, and reversing the recent trend of consolidation that has depleted print culture and turned book business into a blockbuster market.

Epstein has founded a new company, OnDemand Books, to realize this vision, and earlier this year, they installed test versions of the new “Espresso Book Machine” (pictured) — capable of producing a trade paperback in ten minutes — at the World Bank in Washington and (with no small measure of symbolism) at the Library of Alexandria in Egypt.

Epstein is confident that, with a print publishing system as distributed and (nearly) instantaneous as the internet, the codex book will persist as the dominant reading mode far into the digital age.

google to scan spanish library books

The Complutense University of Madrid is the latest library to join Google’s digitization project, offering public domain works from its collection of more than 3 million volumes. Most of the books to be scanned will be in Spanish, as well as other European languages (read more in Reuters , or at the Biblioteca Complutense (en espagnol)). I also recently came across news that Google is seeking commercial partnerships with english-language publishers in India.

The Complutense University of Madrid is the latest library to join Google’s digitization project, offering public domain works from its collection of more than 3 million volumes. Most of the books to be scanned will be in Spanish, as well as other European languages (read more in Reuters , or at the Biblioteca Complutense (en espagnol)). I also recently came across news that Google is seeking commercial partnerships with english-language publishers in India.

While celebrating the fact that these books will be online (and presumably downloadable in Google’s shoddy, unsearchable PDF editions), we should consider some of the dynamics underlying the migration of the world’s libraries and publishing houses to the supposedly placeless place we inhabit, the web.

No doubt, Google’s scanners are aquiring an increasingly global reach, but digitization is a double-edged process. Think about the scanner. A photographic technology, it captures images and freezes states. What Google is doing is essentially photographing the world’s libraries and preparing the ultimate slideshow of human knowledge, the sequence and combination of the slides to be determined each time by the queries of each reader.

But perhaps Google’s scanners, in their dutifully accurate way, are in effect cloning existing arrangements of knowledge, preserving cultural trade deficits, and reinforcing the flow of knowledge power — all things we should be questioning at a time when new technologies have the potential to jigger old equations.

With Complutense on board, we see a familiar pyramid taking shape. Spanish takes its place below English in the global language hierarchy. Others will soon follow, completing this facsimile of the existing order.

two copyright manifestos out of britain

The British Academy:

“…the copyright system may in important respects be impeding, rather than stimulating, the production of new ideas and new scholarship in the humanities and social sciences.”

The British Library:

“Existing legislation urgently needs to be updated, though the manner in which this is achieved has the potential to nurture or curtail the development of new kinds of creativity and new models of public and private sector value.”

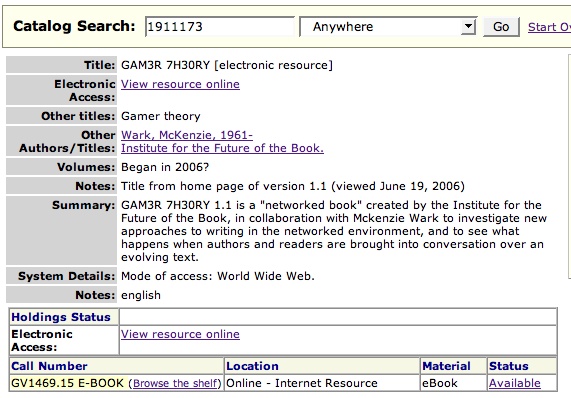

GAM3R 7H30RY found in online library catalog

Here’s a wonderful thing I stumbled across the other day: GAM3R 7H30RY has its very own listing in North Carolina State University’s online library catalog.

The catalog is worth browsing in general. Since January, it’s been powered by Endeca, a fantastic library search tool that, among many other things, preserves some of the serendipity of physical browsing by letting you search the shelves around your title.

(Thanks, Monica McCormick!)

what’s important to save

Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw visited for lunch earlier in the week and gave us a preview of the very interesting presentation they made later that day about the SF-based Prelinger Library . Beginning in the 70s Rick started collecting film and video that no one else seemed to want — industrials (e.g. GM’s worldfair and auto show films), educational films (think “how to be popular”, “how to be a good citizen” and how to make the perfect jelly), and filmed advertisements to be shown in movie theaters and early TV. Rick’s contention, as the first serious media archaeologist, was that these films that no one intended to be saved or seen again — ephemeral films — often provided much more insight about howsociety has evolved in the twentieth century than the big budget hollywood films which tend to be more self-conscious and indirect.

Below are a few clips from some of my favorites. the clip from “A Date With Your Family” contains one of the scariest moments i’ve ever encountered in film, when at the end of the clip, the narrator remarks as “father” returns from his day at the office . . . . that “these boys greet their dad AS THOUGH they are genuinely glad to see him, AS THOUGH they had really missed being away from him during the day . . . ” In the second clip, “A Young Man’s Fancy,” the daughter in a pensive mood says “I was just thinking” and the mother says incredulously, “thinking?” as if that’s the most outlandish thing she can imagine her daughter doing.

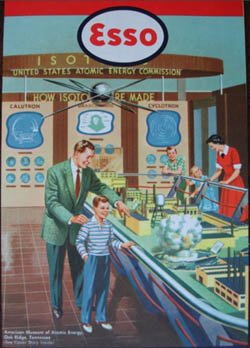

A few years ago, the Library of Congress, recognizing the inestimable value of Rick’s collection, bought the whole kit and caboodle. Since then, Rick and his partner, Megan Shaw have turned their attention to print, building a library of unusual books, periodicals and print ephemera; e.g. an invaluable collection of ESSO’s state maps from the fities that favors serendipitous browsing and remix. (the cover of the ESSO map below depicts a young boy being introduced by his dad to the wonders of nuclear fusion).

The following is from the description on the library’s website:

Though libraries live on (and are among the least-corrupted democratic institutions), the freedom to browse serendipitously is becoming rarer. Now that many research libraries are economizing on space and converting print collections to microfilm and digital formats, it’s becoming harder to wander and let the shelves themselves suggest new directions and ideas. Key academic and research libraries are often closed to unaffiliated users, and many keep the bulk of their collections in closed stacks, inhibiting the rewarding pleasures of browsing. Despite its virtues, query-based online cataloging often prevents unanticipated yet productive results from turning up on the user’s screen. And finally, much of the material in our collection is difficult to find in most libraries readily accessible to the general public.

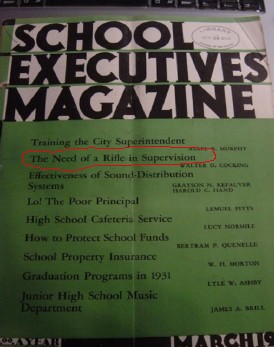

While listening to Rick and Megan’s talk i had a minor AHA moment. a lot of our skepticism and concern about Google centers on the inherent dangers of a private company being entrusted with the care and feeding of our increasingly digitize culture. When Rick and Megan showed the cover of School Executives, a journal from the 40s, which featured an article on the value of teachers toting guns to enforce classroom discipline, i realized that Google’s digitization efforts focus entirely on codex books (maybe to be extended to periodicals that libraries have bothered to store). but the invaluable materials that might be called “print-based” ephemera — pamphlets, marketing materials, off-beat journals, zines etc. — will be absent in the future. The sad thing about this, as we know from Rick’s ephemeral film collection, is that often these pieces that were never meant to survive tell us more about how our culture evolved and how we’ve ended up where we are, than many self-conscious efforts conceived with permanence in mind.

the year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit launches

The year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit started last night at Proteus Gowanus, an arts organization located in Brooklyn, New York. The opening event was a standing room only presentation by Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw Prelinger who run the Prelinger Library. Their presentation focused on their work leading up to the creation of the library, a highly curated collection of printed matter they have accumulated over two decades. The collection has a strong focus on books, print ephemera and periodicals. The 40,000 plus items are now on display and open to the public in downtown San Francisco. Visitors are allowed to stop in and browse items from the collection. The library’s collection is an amazing experiment in curation, taxonomy (they created their own,) and commentary on how libraries are shifting forms. We were fortunate to have lunch with Rick and Megan before their event. Everyone at the institute found their work very inspiring and they will be discussed in more detail in upcoming posts.

The year-long Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit started last night at Proteus Gowanus, an arts organization located in Brooklyn, New York. The opening event was a standing room only presentation by Rick Prelinger and Megan Shaw Prelinger who run the Prelinger Library. Their presentation focused on their work leading up to the creation of the library, a highly curated collection of printed matter they have accumulated over two decades. The collection has a strong focus on books, print ephemera and periodicals. The 40,000 plus items are now on display and open to the public in downtown San Francisco. Visitors are allowed to stop in and browse items from the collection. The library’s collection is an amazing experiment in curation, taxonomy (they created their own,) and commentary on how libraries are shifting forms. We were fortunate to have lunch with Rick and Megan before their event. Everyone at the institute found their work very inspiring and they will be discussed in more detail in upcoming posts.

The spirit of the Prelinger’s work is great introduction to Proteus Gowanus’ exploration on this theme. Libraries are in flux, as they have historically played many roles, including distributors of knowledge, places that support research, archives and now quite often, community centers. For the next year, Proteus Gowans is displaying in their gallery, artwork related to libraries as well as hosting presentations and films. Photos by Nina Katchadourian depict the spines of various books which compose textual messages. Artist Jeffrey Schiff’s contribution plays with the Dewey Decimal System and themes of categorizations by applying call numbers to everyday objects and spaces. Also, included in the exhibit is the Reanimation Library, curated and owned by Andrew Beccone. This collection preserves books that are not typically saved in public and academic libraries, including titles such as “Simplified Taxidermy,” “A Guide to Gymnastics” and “Judo: Thirty Lessons in the Modern Science of Jiu-Jitsu.” The next event is Deirdre Lawrence, the Principal Librarian and Coordinator of Research Services Museum Libraries and Archives at the Brooklyn Museum, on October 27th.

Issues of funding, the rise of the digital, and intellectual property are all changing the role of libraries and how people interact with them. Many large questions are being asked about the future of the library. The most basic one being, what will it look like? Will it start to shift towards smaller nodes of semi-private collections connected to each other via the network? Are collections of books going to be increasingly less tied to physical spaces? Will the public library continue to shift towards acting more like a community center? Are publishers and libraries going fuse and produce a new hybrid institution?

Realizing that libraries are going through a cultural as well as technological transformation, Proteus Gowanus is embarking on an year long examination in a variety of media which track these changes. They may not be able to answer any of these questions directly, but they are certainly providing new directions and understandings. Most importantly, the Interdisciplinary Library Exhibit is opening up the conversation to a diversity of voices, including the public at large.

google flirts with image tagging

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

Ars Technica reports that Google has begun outsourcing, or “crowdsourcing,” the task of tagging its image database by asking people to play a simple picture labeling game. The game pairs you with a randomly selected online partner, then, for 90 seconds, runs you through a sequence of thumbnail images, asking you to add as many labels as come to mind. Images advance whenever you and your partner hit upon a match (an agreed-upon tag), or when you agree to take a pass.

I played a few rounds but quickly grew tired of the bland consensus that the game encourages. Matches tend to be banal, basic descriptors, while anything tricky usually results in a pass. In other words, all the pleasure of folksonomies — splicing one’s own idiosyncratic sense of things with the usually staid task of classification — is removed here. I don’t see why they don’t open the database up to much broader tagging. Integrate it with the image search and harvest a bigger crop of metadata.

Right now, it’s more like Tom Sawyer tricking the other boys into whitewashing the fence. Only, I don’t think many will fall for this one because there’s no real incentive to participation beyond a halfhearted points system. For every matched tag, you and your partner score points, which accumulate in your Google account the more you play. As far as I can tell, though, points don’t actually earn you anything apart from a shot at ranking in the top five labelers, which Google lists at the end of each game. Whitewash, anyone?

In some ways, this reminded me of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an “artificial artificial intelligence” service where anyone can take a stab at various HIT’s (human intelligence tasks) that other users have posted. Tasks include anything from checking business hours on restaurant web sites against info in an online directory, to transcribing podcasts (there are a lot of these). “Typically these tasks are extraordinarily difficult for computers, but simple for humans to answer,” the site explains. In contrast to the Google image game, with the Mechanical Turk, you can actually get paid. Fees per HIT range from a single penny to several dollars.

I’m curious to see whether Google goes further with tagging. Flickr has fostered the creation of a sprawling user-generated taxonomy for its millions of images, but the incentives to tagging there are strong and inextricably tied to users’ personal investment in the production and sharing of images, and the building of community. Amazon, for its part, throws money into the mix, which (however modest the sums at stake) makes Mechanical Turk an intriguing, and possibly entertaining, business experiment, not to mention a place to make a few extra bucks. Google’s experiment offers neither, so it’s not clear to me why people should invest.