Princeton is the latest university to partner up with the Google library project, signing an agreement to have 1 million public domain books scanned over the next six years. Over at ALA Techsource Tom Peters voices the growing unease among librarians worried about the long-term implications of commercial enclosure of the world’s leading research libraries.

Category Archives: library

national archives sell out

This falls into the category of deeply worrying. In a move reminiscent of last year’s shady Smithsonian-Showtime deal, the U.S. National Archives has signed an agreement with Footnote.com to digitize millions of public domain historical records — stuff ranging from the papers of the Continental Congress to Matthew B. Brady’s Civil War photographs — and to make them available through a commercial website. They say the arrangement is non-exclusive but it’s hard to see how this is anything but a terrible deal.

Here’s a picture of the paywall:

Dan Cohen has a good run-down of why this should set off alarm bells for historians (thanks, Bowerbird, for the tip). Peter Suber has: the open access take: “The new Democratic Congress should look into this problem. It shouldn’t try to undo the Footnote deal, which is better than nothing for readers who can’t get to Washington. But it should try to swing a better deal, perhaps even funding the digitization and OA directly.”

Elsewhere in mergers and acquisitions, the University of Texas Austin is the newest partner in the Google library project.

report on scholarly cyberinfrastructure

The American Council of Learned Societies has just issued a report, “Our Cultural Commonwealth,” assessing the current state of scholarly cyberinfrastructure in the humanities and social sciences and making a series of recommendations on how it can be strengthened, enlarged and maintained in the future.

The definition of cyberinfastructure they’re working with:

“the layer of information, expertise, standards, policies, tools, and services that are shared broadly across communities of inquiry but developed for specific scholarly purposes: cyberinfrastructure is something more specific than the network itself, but it is something more general than a tool or a resource developed for a particular project, a range of projects, or, even more broadly, for a particular discipline.”

I’ve only had time to skim through it so far, but it all seems pretty solid.

John Holbo pointed me to the link in some musings on scholarly publishing in Crooked Timber, where he also mentions our Holy of Holies networked paper prototype as just one possible form that could come into play in a truly modern cyberinfrastructure. We’ve been getting some nice notices from others active in this area such as Cathy Davidson at HASTAC. There’s obviously a hunger for this stuff.

worth reading

In 2005, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, the President of the Bibliothè que Nationale (France’s equivalent of the Library of Congress) wrote one of the most trenchant critiques of Google’s intention to digitize millions of books from a number of major libraries. Jeanneney expanded on his original essay and this past October, The University of Chicago Press published a translation of Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge: A View from Europe. In this December’s D-Lib Magazine, there’s a superb precis and analysis of Jeanneney’s book by Dave Bearman.

how would you design the iraq study group report for the web?

The “Iraq Study Group Report” paperback could have been wrapped in a brown paper bag, its title scrawled in Magic Marker. It would still sell. This is a book, unlike trillions of others on the market, whose substance and national import sell it, not its cover…Disproving the adage, this genre of book can indeed be judged by its cover. From the reports on the Warren Commission to Watergate, Iran-contra and now the Iraq war, such books are anomalies for a publishing industry that churns out covers intended to seduce readers, to reach out and grab them, and propel them to the cash register.

How would you design an unauthorized web edition of the ISG Report? Would you keep to the sober, no-nonsense aesthetic of the iconic print editions of past government documents like the 9/11 Commission Report or the Warren Commission Report? Or would you shake things up? A far more interesting question: what functionality would you add? What kind of discussion capabilities would you build into it? Who would you most like to see annotate or publicly comment on the document?

The electronic edition that has been making the rounds is an austere PDF made available by the United States Institute of Peace. A far more useful resource for close reading of the text was put out by Vivismo as a demonstration of its new Velocity Search Engine. They crawled the PDF and broke it into individual paragraphs, adding powerful clustered search tools.

The US Government Printing Office has a slew of public documents available on its website, mostly as PDFs or bare-bones HTML pages. How should texts of “national import” be reconceived for the network?

brewster kahle on the google book search “nightmare”

“Pretty much Google is trying to set themselves up as the only place to get to these materials; the only library; the only access. The idea of having only one company control the library of human knowledge is a nightmare.”

From a video interview with Elektrischer Reporter (click image to view).

(via Google Blogoscoped)

google makes slight improvements to book search interface

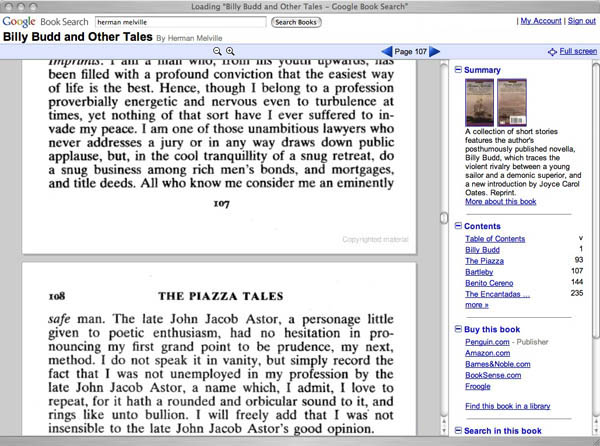

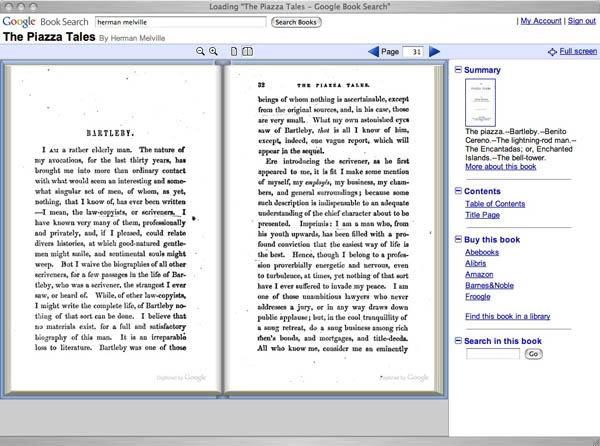

Google has added a few interface niceties to its Book Search book viewer. It now loads multiple pages at a time, giving readers the option of either scrolling down or paging through left to right. There’s also a full screen reading mode and a “more about this book” link taking you to a profile page with links to related titles plus references and citations from other books or from articles in Google Scholar. Also on the profile page is a searchable keyword cluster of high-incidence names or terms from the text.

Above is the in-copyright Signet Classic edition of Billy Budd and Other Tales by Melville, which contains only a limited preview of the text. You can also view the entire original 1856 edition of Piazza Tales as scanned from the Stanford Library. Public domain editions like this one can now be viewed with facing pages.

Still a conspicuous lack of any annotation or social reading tools.

dutch fund audiovisual heritage to the tune of 173 million euros

Larry Lessig writes in Free Culture:

Why is it that the part of our culture that is recorded in newspapers remains perpetually accessible, while the part that is recorded on videotape is not? How is it that we’ve created a world where researchers trying to understand the effect of media on nineteenth-century America will have an easier time than researchers trying to understand the effect of media on twentieth-century America?

Twentieth century Holland, it turns out, will be easier to decipher:

The Netherlands Government announced in its annual budget proposal the support for the project “Images for the Future” (in Dutch). Images for the Future is a large-scale conservation and digitalisation operation comprising 285,000 hours of film, television and radio recordings, and 2.9 million photos. The investment of 173 million euro, is spread over a period of seven years.

…It is unprecedented in its scale and ambition. All these films, programmes and photos will be made available for educational and creative purposes. An infrastructure for digital distribution will also be developed. A basic collection will be made available without copyright or under a Creative Commons licence. Making this heritage digitally available will lead to innovative applications in the area of new media and the development of valuable services for the public. The income/expense analysis included in the project plan shows that on balance the project will produce a positive social effect in the Dutch economy to the value of 20 to 60 million euros.

— from Association of Moving Image Archivists list-server

Pretty inspiring stuff.

Eddie Izzard once described the Netherlandish brand of enlightenment in a nutshell: “The Dutch speak four languages and smoke marijuana!” We now see that they also deem it wise policy to support a comprehensive cultural infrastructure for the 21st century, enabling their citizens to read, quote and reuse the media that shapes their world (while they whiz around on bicycles over tidy networks of canals). Not so here in the States where the government works for the monopolies, keeping big media on the dole through Sonny Bono-style protectionism. We should pass our benighted politicos a little of what the Dutch are smoking.

laurels

We recently learned that the Institute has been honored in the Charleston Advisor‘s sixth annual Readers Choice Awards. The Advisor is a small but influential review of web technologies run by a highly respected coterie of librarians and information professionals, who also hold an important annual conference in (you guessed it) Charleston, South Carolina. We’ve been chosen for our work on the networked book:

The Institute for the Future of the Book is providing a creative new paradigm for monographic production as books move from print to the screen. This includes integration of multimedia, interviews with authors and inviting readers to comment on draft manuscripts.

A special award also went to Peter Suber for his tireless service on the Open Access News blog and the SPARC Open Access Forum. We’re grateful for this recognition, and to have been mentioned in such good company.

row after row after row after row

I want to tell you about one scene in a wonderful documentary, DOC, that just opened the Margaret Mead Film Festival at the Museum of Natural History in New York. Doc Humes was the founder of the Paris Review. Made by his daughter, Immy, the film follows Immy as she tries to uncover the layers of her father’s complex life. At one point she finds out that he made a feature film and she tries to find the footage. She gets a tip that Jonas Mekas may have a copy at Anthology Film Archives in the east village in New York. She goes to visit Mekas and takes her camera. Mekas takes her into the vast underground storeroom and points at row after row after row after row of film cans. The point of the shot is that looking for the film on these shelves — even if it were known to be here, which it isn’t — is a hopeless task. Nothing seems to be marked; there is no order. Rather than a salvation for the rich film culture that came out of NY in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, it seems that the Anthology Film Archive may become a graveyard.

Seeing this made me wonder about the decisions we make as a society about what to keep and what not to keep. There may be important film in those cans or there may not be. How do we decide whether to gather the resources to find out?